Sitting on the dock of the eBay

End of the week already, and so time for a workmanlike round up of what’s floated to the surface on eBay recently.

Exhibit A is this Littlehampton poster from the States, which is a bit battered but not beyond the work of man to restore (for something which is, see below). Following on from yesterday’s thoughts, I wonder how it got to the States, and how many Americans holidayed in Littlehampton rather than the Hamptons as a result?

It’s by Studio 7 (whose work has recently started to cross my radar, does anyone know anything about them?) and dates from 1960 says the National Railway Museum. Here’s their copy looking quite nice.

And it’s filed in America under Transportation Collectables/British Airways, so might not get that much notice, should you be hoping for a bargain.

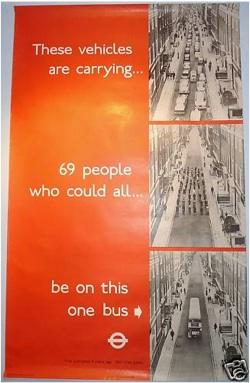

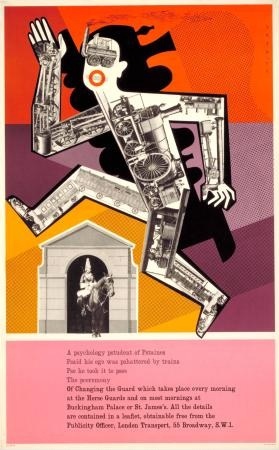

Next, a 1960s/1970s London Transport poster, which is not bad, although would be better for not being the 1973 reprint with added text.

I can’t better the eBay description:

This is an original 1973 copy of the famous poster by well-known industrial photographer Dr Heinz Zinram. First issued in 1965 and then re-issued in 1973 with the added slogan ” First published 8 years ago; still true today”, it shows three versions of a street scene; the first full of cars, then the people from those cars on the street and, finally, one Routemaster bus which has soaked up all 69 people.

Its message would do as well today as in 1965 and 1973. So perhaps posters don’t work that well after all.

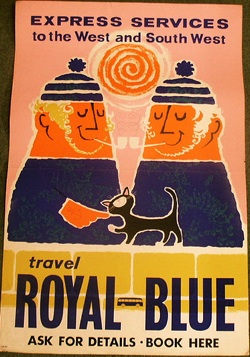

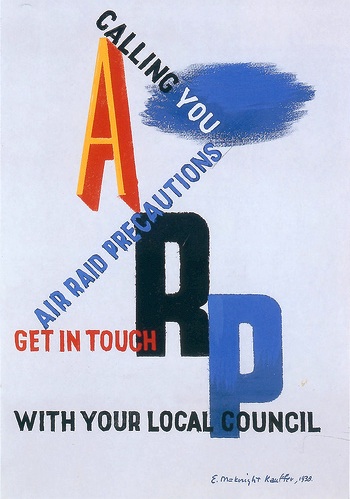

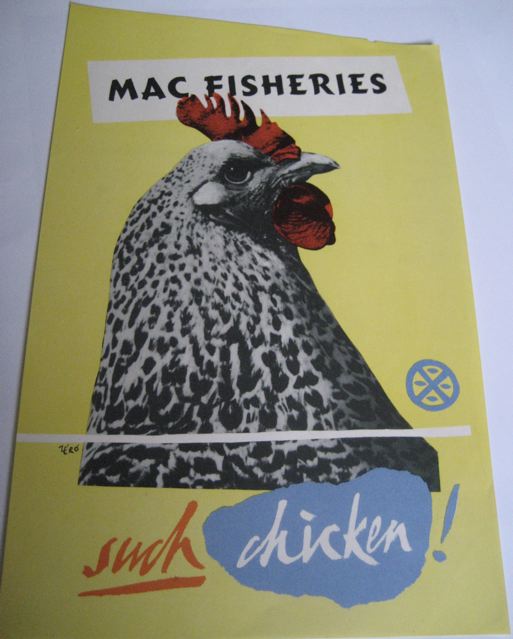

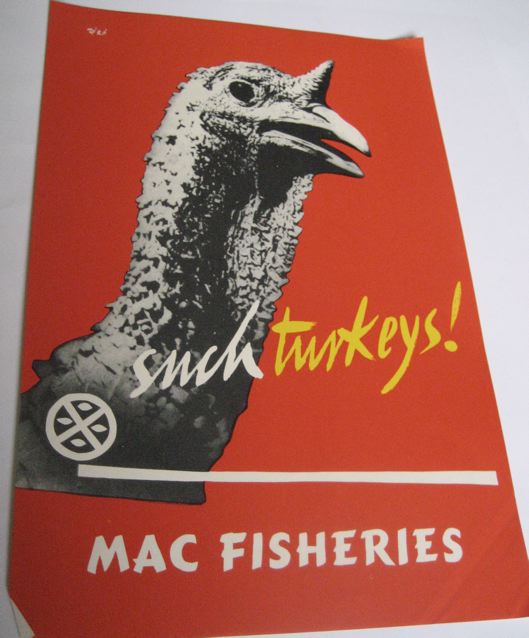

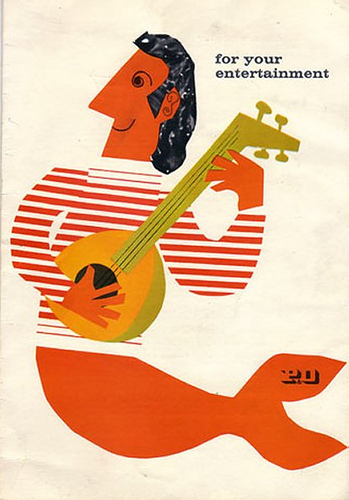

And finally, proving that a) everything which has a named designer is not necessarily gold and b) people will try to sell absolutely anything on eBay, a Daphne Padden poster. Or at least some of one.

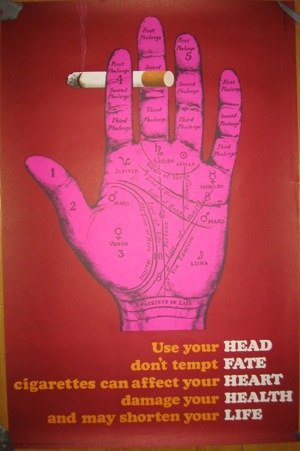

Now Daphne Padden is an under-rated designer, but that poster is not typical of her normally much less traditional style:

Unlike the BEA one, this is wonderful stuff, and Padden deserves more appreciation than she currently gets. If you want to see more of her graphic style, there’s a good collection of her work on Flickr and not really anywhere else. A set (quite possibly this set) came up on eBay a couple of years ago, and the more I look at these, the more I wish we’d bought at least one of them. Especially the one above with the cat. Ah well, next time.