I was asked to help out earlier this week. Could I find a few vintage posters to act as inspiration for a designer doing a poster for a retro tea-dance? Cakes, bunting, dancing, something nice and festive – it’s not that difficult to imagine the sort of thing. But that sort of thing turned out to be rather harder to find in reality.

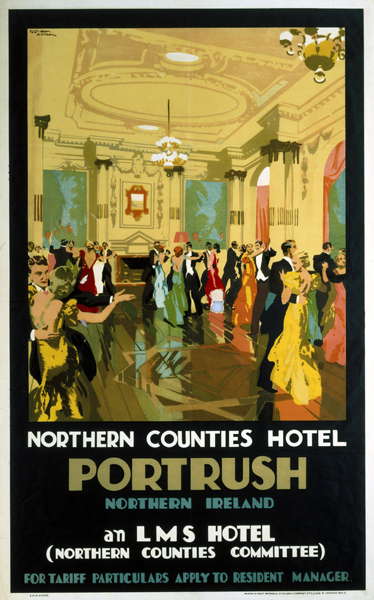

If you go back to the 1930s, there was at least dancing, as in this Gordon Nicoll poster from 1932.

As well as in this rather wonderful London Transport design by Clifford and Rosemary Ellis from 1936.

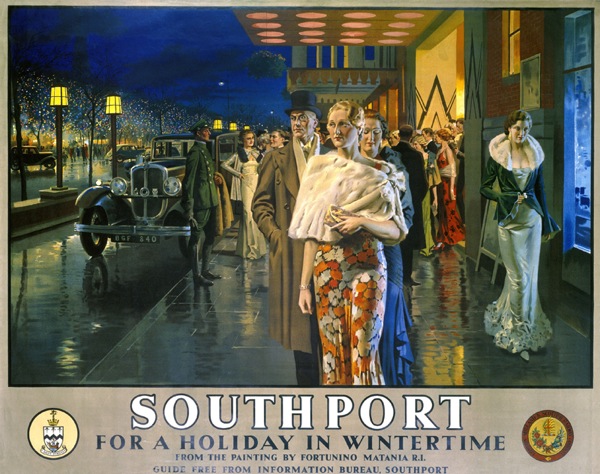

There’s some glamourous going out in a couple more posters, as in this 1925 Fortunino Matania poster for Southport (on sale once more at Onslows this afternoon if you have a few thousand pounds to spare).

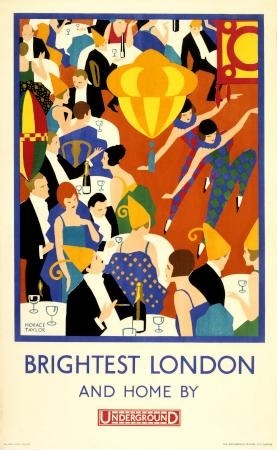

Which was available in London as well as Southport, it seems.

Horace Taylor, 1924, since you ask.

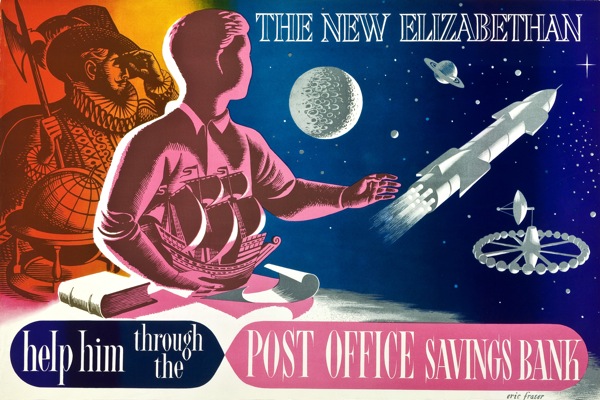

But of cakes and bunting, or indeed anything remotely relevant from the 1950s, not a sniff. The closest I could get was this.

Which isn’t really what I was after. Somewhere – and I have lost it and would love to see it again if anyone can help – there is also a 1950s poster of a husband bringing a tray of tea to his family on the beach. But even that isn’t really doing what my friend wanted the posters to do.

What’s happening here is something that I’ve mentioned time and again on this blog, the bending of visual memory. Today, we want to see the 1950s in terms of tea, dancing and bunting, and so that is how we expect them to depict themselves as well. Except they won’t oblige, mainly because they are too busy building a modern, post-war future – as encapsulated in Nick Morgan’s prize winning poster from last week.

No sign of Coronation bunting here, oh no. Not when there’s history to be made instead.

In this respect, bunting, vintage bunting, retro bunting on posters for tea dances work in much the same way as our reusing of wartime posters (full post on that subject here). The meanings tell us far more about ourselves and our worries about the world than they will ever reveal about the past.

Back in the 1950s, bunting was something that you got out for your village fete or Coronation street party, and then put away again.

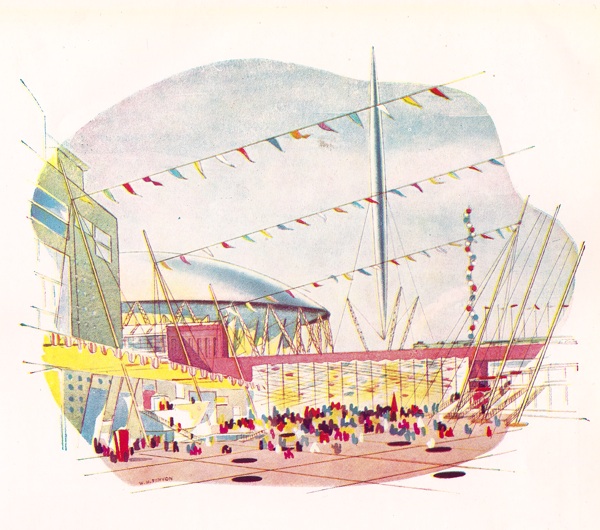

It definitely meant festive, and so appeared in people’s imaginings of the Festival of Britain.

Although interestingly it was nothing like as prominent in the actual event.

Although, of course, every single article about the South Bank anniversary last year had to make mention of getting out the bunting nonetheless.

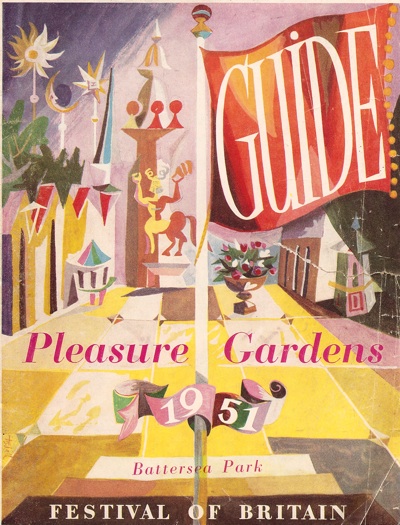

You can also find a small string of the stuff on the cover of the Battersea Pleasure Gardens brochure too. Again it’s operating as a sign here: this is not normal life but a carnival. We are going to have fun.

Bunting in the 1950s was just an everyday object that you got out for the jollities and then put back in the cupboard, nothing worth making a fuss about. Certainly not worth putting on posters.

Nowadays though, bunting is not just a thing, but a cultural phenomenon, as even the briefest of Google image searches will reveal.

It represents, amongst many other things*, a desire to return to a more simple life of making our own entertainments. A life which had so few visual stimuli that we were pleased with bunting. A sense of community too. This is all well and good – and indeed perfect for a nostalgic tea dance. I don’t have any problems with that. Just as long as we stop expecting to find it having the same meanings in the 1950s too.

*Bunting does become more problematic when you look at it through the lens of Thorsten Veblen and conspicuous consumption. Bunting isn’t only the fetishisation of an utterly unnecessary object to prove that you have money to spend, it’s also a signifier of conspicuous leisure, because if you’ve got time to shop for, stitch or even worry about bunting, you do have a fair amount of spare time on your hands. I preferred the stuff in its 1950s incarnation, I think.

Games even had bunting hanging from his FOB logo!

Lovely to see the Clifford & Rosemary Ellis’s poster, marvellous designers, their New Naturalist covers are an unending delight

Ah that’s true about the logo, I missed that one. Anything else out there that I’ve forgotten? Clearly getting worked up over bunting was clouding my mind.

Clifford and Rosemary Ellis are interesting – they don’t really get the attention they deserve, I think partly because their work is spread across a few different genres. I think I’ve tried to find out about them before but not had much luck, perhaps I should have another go. As ever, if anyone else out there knows stuff, then please do get in touch.

There is a good little biography on C & R Ellis (including some examples of their posters) in Art of the New Naturalists by Peter Marren and Robert Gillmor (Collins ISBN 9780007284719)

Ah, thank you for that. I might have to invest in a copy.

Rather belatedly…Further to my comment about the FoB emblem, I have noticed in Games’ book, Over My Shoulder, a remark about the flags being added because of a festival policy change to “include more gaiety”! There is certainly no bunting in his original sketches for the logo, but as they were made in 1948 the policy change might have been at quite an early stage in the planning.

Yes, that does actually ring a bell for me now that you mention it, thank you.

I’ve also, in response to Nick’s comment above, invested in the Art of the New Naturalists book and so may well be posting about the Ellises in due course.