Not small.

Having said that nothing new and interesting has turned up for a while, I am just about to prove myself wrong. But that’s probably a good thing. At least I think it is.

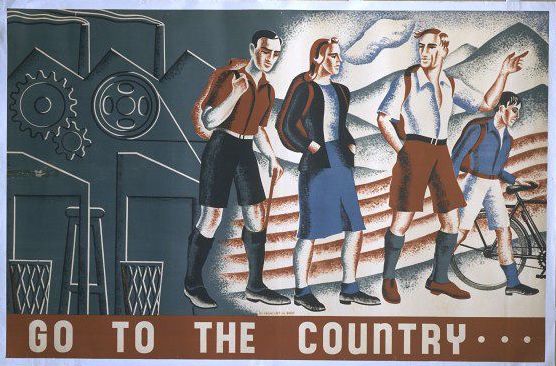

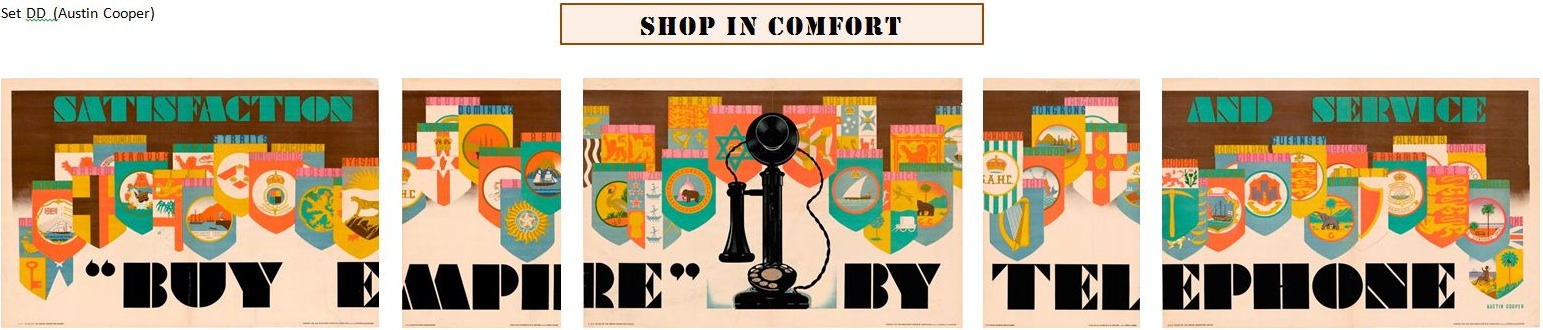

Anyway, I was looking at the V&A’s collection of Empire Marketing Board posters (as anyone might do on a quiet afternoon) and my search turned up this.

Or rather these, as there are three images in the one record.

The description is:

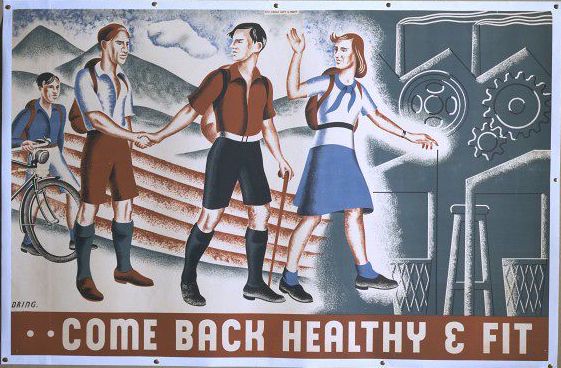

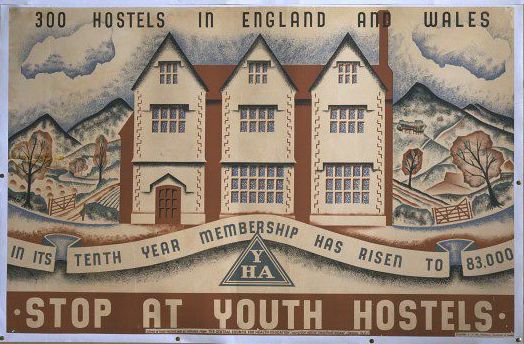

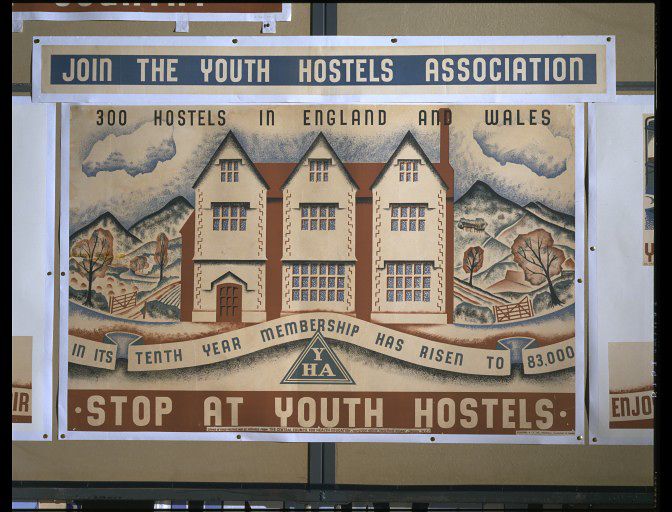

Join the Youth Hostels Association. Poster, originally printed on 7 sheets, 2 of which were later cut by the artist, issued by the Central Council of Health Education through the Agency of Abbey Arts Ltd.

They were designed by Lilian Dring (which auto-correct wants to change to everything but her actual surname), and produced in 1940, all of which is fascinating for at least three reasons.

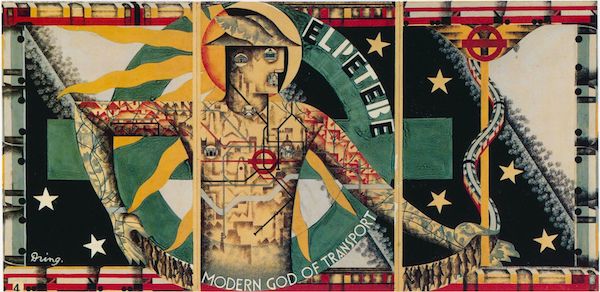

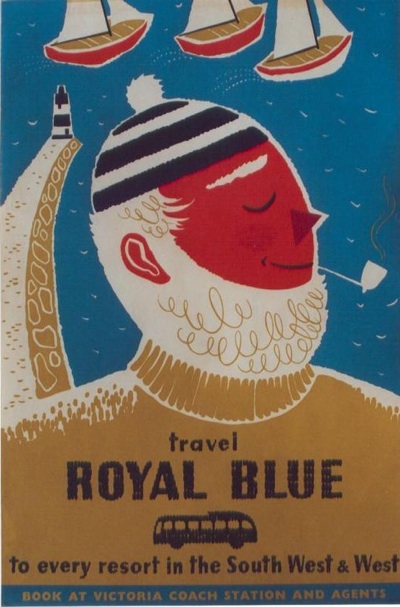

Firstly, there aren’t enough posters out there by Lilian Dring. I’ve seen very few examples of her work at all, and yet she designed this amazing, albeit never used poster for London Underground.

It’s brave, it’s heroic, its modernist – and by a woman designer. I think she should have been as famous as McKnight Kauffer.

On top of that, these posters were produced in 1940. At this point, almost all commercial poster advertising was prohibited, and the Ministry of Information was pumping out posters of every which kind telling the British population what to do, join, eat and save. It’s really quite surprising to find another government body engaging in what could be seen as inessential postering on this scale; I genuinely had no idea that this had happened. It makes me wonder what else got advertised in the first year or two of the war – and that’s quite an important question. In the later years of the way, people complained about the omnipresence of propaganda. But if, in 1940, the government’s poster efforts were surrounded by other kinds of messages, it would have made their impact very different.

But one more interesting detail – to me the most fascinating one of all – is lurking in the object history note.

The poster was printed to the same format as the Empire Marketing Board posters on the hoardings for which it was placed in November 1940.

Now one of the many notable things about the Empire Marketing Board poster campaigns were that they were designed for their own, unique, set of hoardings. I’ve written about them in detail elsewhere but they were elongated and set apart, designed to take a very specific set of formats.

That’s three 60 x 40″ 4-sheet posters, two 40 x 25″ Double Royals and then a title strip at the top, in this case by Austin Cooper.

And if we look at the full pictures in the V&A’s catalogue, not only do the Dring posters work as a sequence in just the same way, there are clearly three more in the collection which I’m guessing would fill the remaining slots perfectly.

All of which raises some ideas which I’d never really considered before. The Empire Marketing Board had something like 1700 of its own poster sites in towns and cities across Britain, but it only produced posters between 1927 and 1933. So what happened to those hoardings after the EMB ended? Did they get taken down, or did they moulder and rot? Or, as these posters suggest, were they used by other semi-official, non-commercial advertisers? Because these posters were produced in 1940, seven years after the EMB stopped using them. That’s a long gap, and suggests it was filled by something in the meantime. Will I ever know the answer to that? Probably not. But it’s still an interesting question.

When I started writing about these posters, that was the sum total of my thoughts. But then, I thought, I should probably find out a bit more about Lilian Dring. So I did.

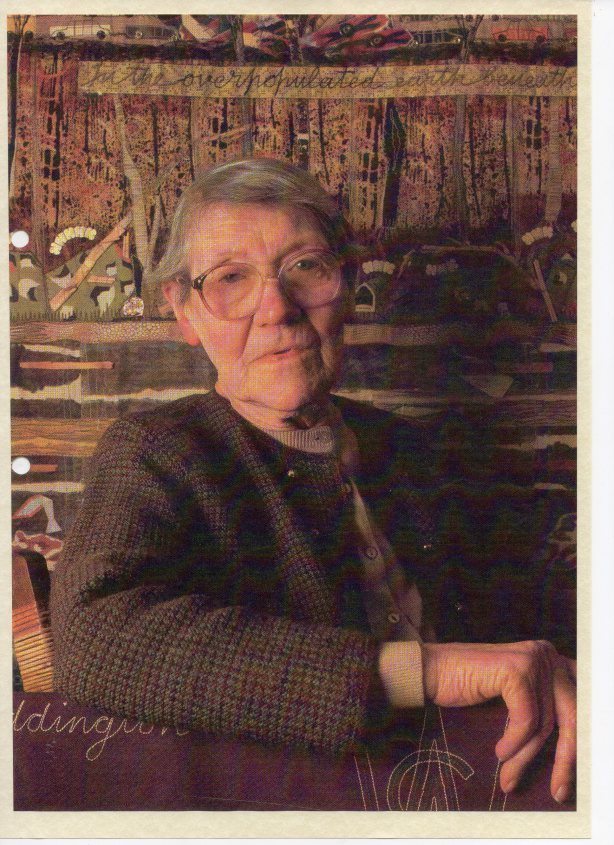

Despite being one of the first students on the Royal College of Art’s Poster Design course, she ended up working in textiles. Now, maybe textiles were always her one real love, I don’t know, but at the same time it’s a course which quite a lot of women end up following. Step away from the big, dominant poster work, that’s for the men – instead why don’t you go off and do something a bit more, well, crafty?

I can’t help reading that kind of narrative into the story of how she changed direction.

She began stitching in 1931 on her mother’s hand-operated 1912 Frister & Rossman machine. […] Her early work, undertaken during the Depression and using scraps, included rag dolls, given as presents to friends’ children, and later the ‘personal pillows’ and ‘music cushions’, which always illustrate articles about Lilian. Recycling thus became a major influence in her life and work.

Now Dring did go on to be quite avant-garde in her use of recycled stuff and I really like the sound of what she was doing.

Her reaction to WW2 was illustrated by a piece called ‘Parable 1’ made in 1941 to cover a bombed out window, by then she may have been living in Twickenham, where she died in 1998. It was in three layers with quotations from Exodus (20, v.4.): In the Heavens above: fighter planes and barrage balloons; In the Earth beneath: bombed-out buildings & ambulances; ‘And in the Shelters (sic) under the Earth: people sleeping in air-raid shelters. She appears to have been deeply disturbed by both the destruction caused by warfare, and later by that caused by pollution of the environment. Most of her work featured appliqué – […] and in a similar work, ‘Parable 2’ made in 1972 (the year after she made a red presentation stole for Canon Blair-Fish, the then Vicar) she used can-pulls, dead gladioli stems and even fur from her kettle.

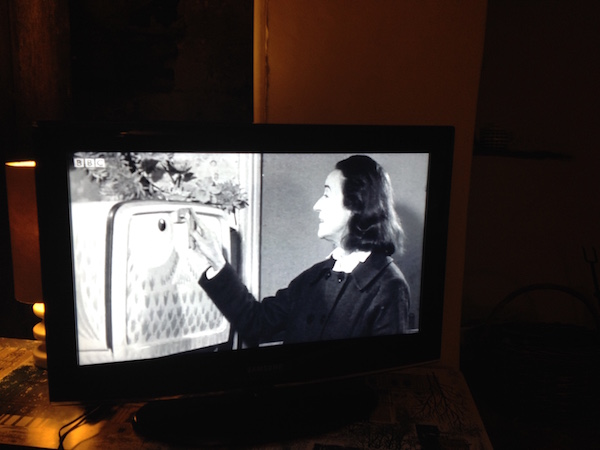

Parable 2 is behind her in this picture, although I can’t identify the kettle fur in there.

I really hope she did exactly what she wanted to do – that textiles were her choice and decision, not something forced upon her by circumstance and the lean times of the 1930s. At the same time, I can’t square those small scraps of reused fabric with the woman who created a set of posters too dramatic and expensive for even Frank Pick to produce, or even the expansive YHA posters. Perhaps she had art in her that had to come out somehow, any which way she could find, and the world told her textiles, not posters.

Women artists and designers are so often made small in this way, pushed into work which can be marginalised or even ignored. All that talent unseen, when it could have been stretched across the biggest billboards in the land; instead it hangs in private houses, or the far end of dark churches. I hope she was happier than I am about it.

All quotes, and the picture of Lilian Dring, are from this website about embroidery in Surbiton, where St Mark’s church contains a number of ecclesiastical embroideries that she designed and made.