Exhibit A today is an ad from our local paper.

It’s here, clearly, to illustrate the after-life of posters. The slogan and image derive, after all, from a poster which will be a hundred years old next year, and yet is still part of our mental furniture. What’s going on?

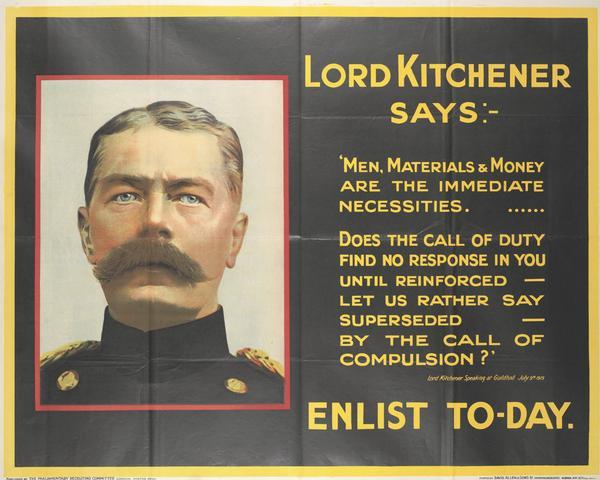

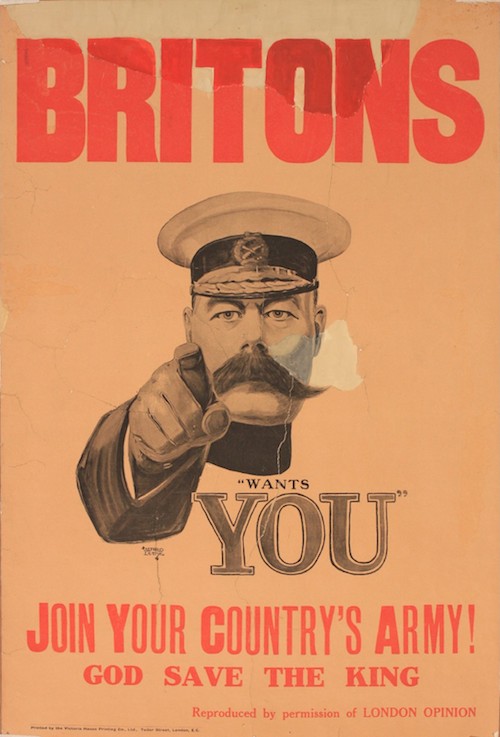

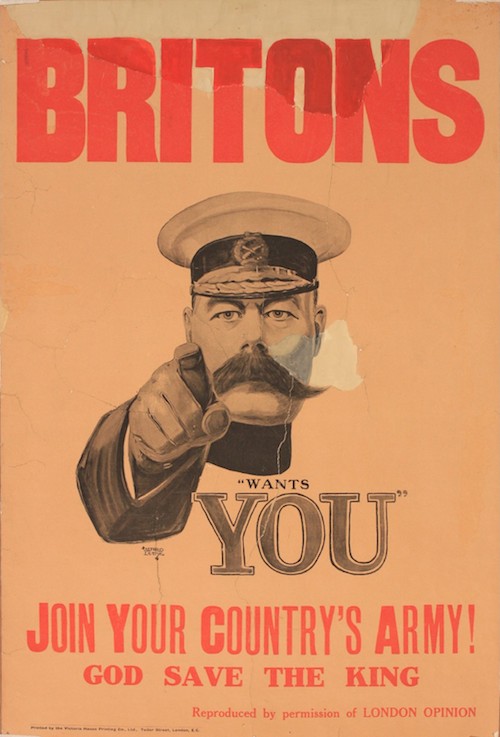

The original is of course this design by Alfred Leete.

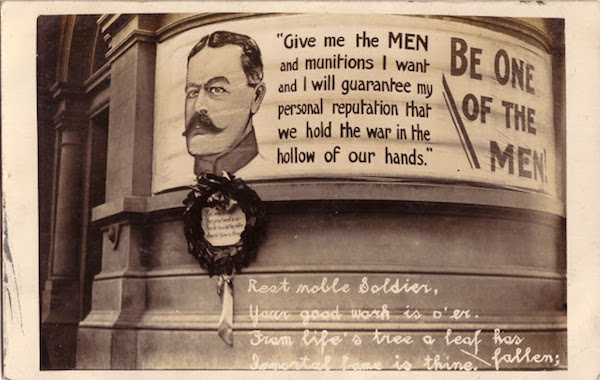

Except it isn’t what you might think. Despite the images that we all carry around in our heads, this drawing almost certainly never existed as a poster. It was designed as a front cover for the mass market magazine London Opinion, and was so popular that it was turned into a postcard and also a print.

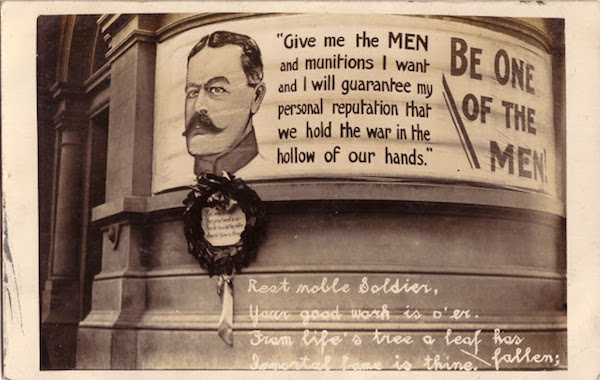

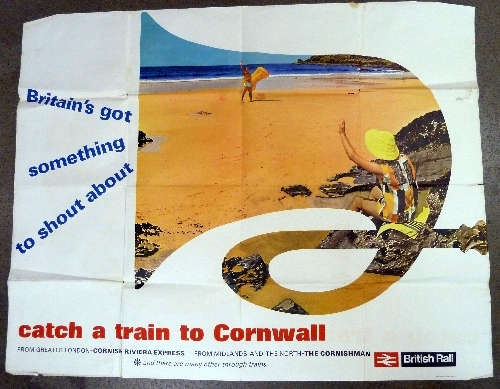

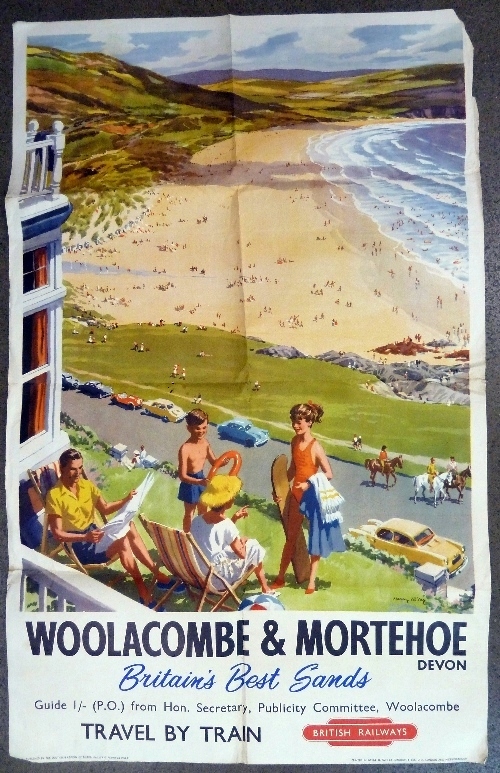

There were certainly lots of pictures of Lord Kitchener plastered out on the streets in 1914.

Not just in Britain, either. Here he is being forceful in New Zealand.

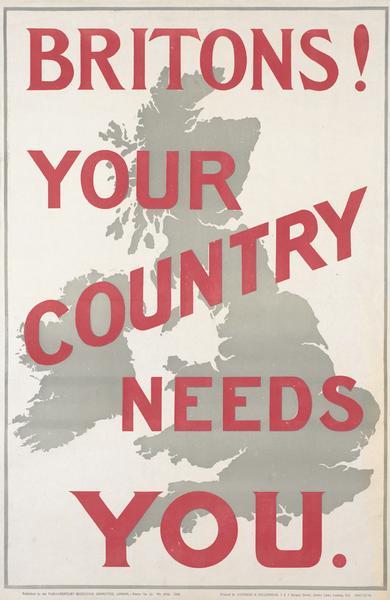

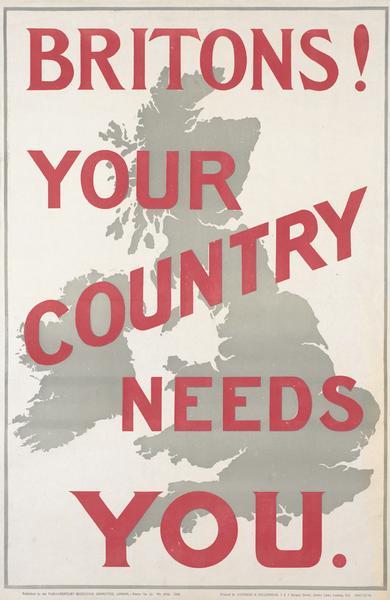

There were also lots of posters using the slogan ‘Your Country Needs You’.

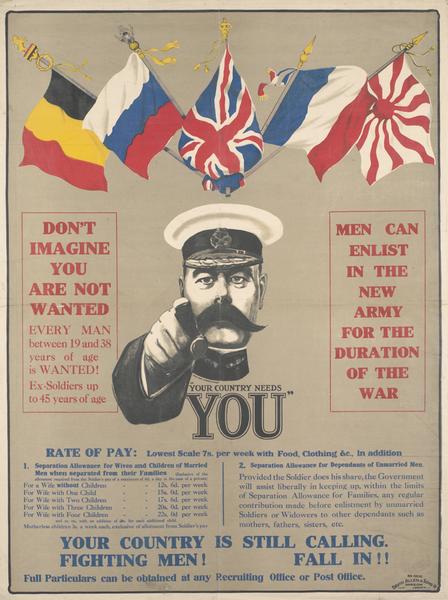

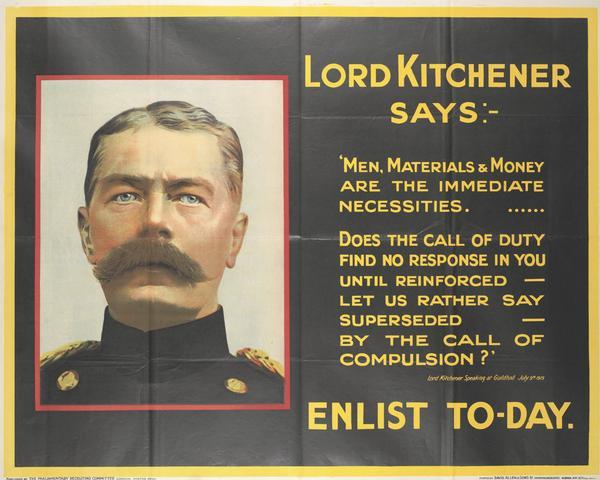

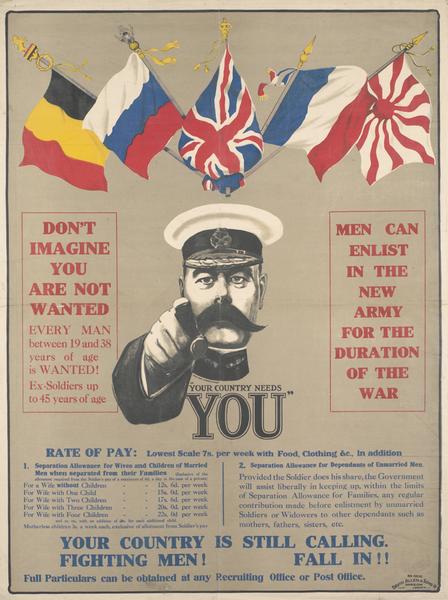

But they never existed together on the same poster. This – as sold at Onslows earlier this summer – is as close as they got to being in the same place.

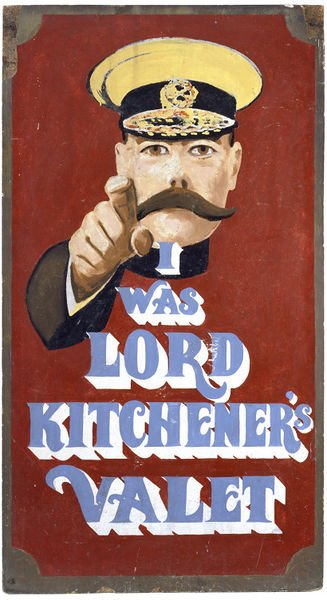

Plus there is also this number, which does at least combine the wording at the image.

Neither of which, however, are the poster of our popular imaginations, though. That’s this one, isn’t it?

Except this is in fact a mock-up, produced quite recently. Aaargh. So how did this poster, which didn’t exist, end up in my newspaper?

The argument about the exact form and origin of the poster has raged all over the internet and newspapers in this centenary year. I mentioned it before, when the Britons poster came up for sale at Onslows, and I don’t pretend to understand the precise ins and outs of it. But that’s OK, because this isn’t really what interests me the most. What I find intriguing is why this particular version – which may or may not have been pasted on walls in 1914 – still haunts us today. I’m not sure I have a definitive answer, but the search does take us along a few interesting byways.

The first of these does, however, involve going back to the argument. An entire book has been written about Lord Kitchener and his pointing finger, Your Country Needs You, which I have read so that you don’t have to. The conclusion is that there may have been a very few privately printed versions out there, although these were few in comparison with the millions of government posters that rolled off the presses, and researchers have yet to find a photograph of one glued to a wall.

But old soldiers being interviewed in the years after the war, when asked about why they volunteered, reply with some regularity that it was because of the poster of Lord Kitchener pointing his finger and saying ‘Your Country Needs You’, which they tend to remember as being plastered on every available surface. So what’s going on? It’s easy to see how people might conflate the slogan and the pictures of Kitchener, and maybe even mix those up with the London Opinion cover. But it seems unlikely that everyone performed exactly the same trick of memory on their own.

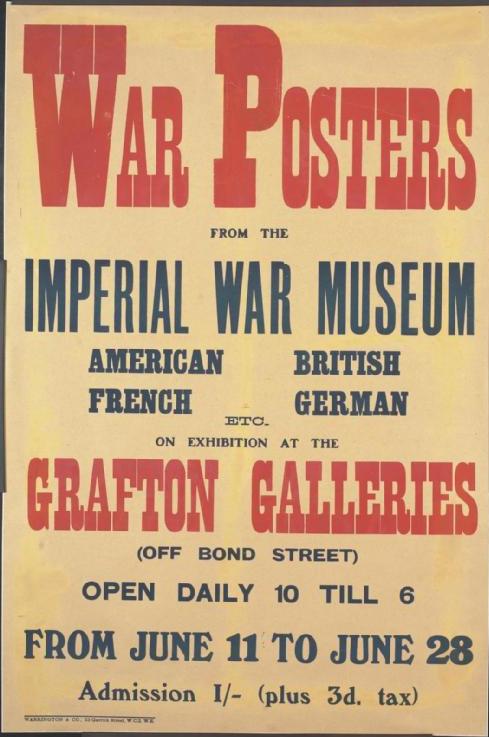

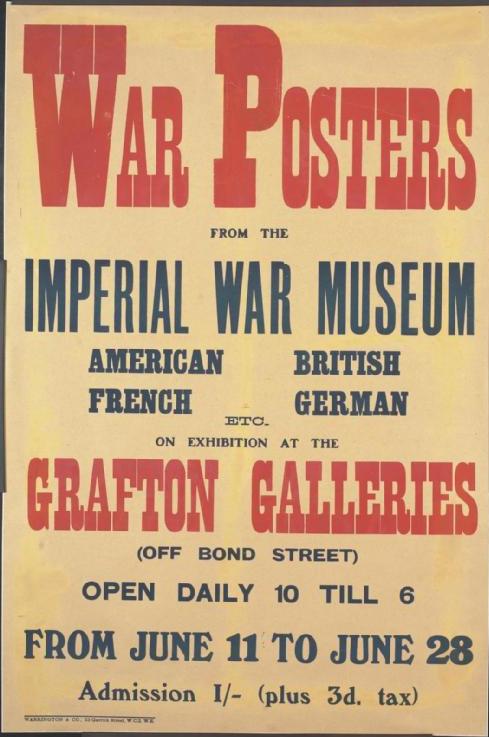

The book argues convincingly that this is all the Imperial War Museum’s fault. The museum was founded in 1917 specifically to record the events of the Great War and as a commemoration of all of those who died. As part of this, it collected the recruitment posters of the time (there were quite a few out there to be collected, warehouses full of them in fact, left over after conscription had been introduced). It also managed to collect the London Opinion print, and mis-catalogued it as a poster. Thus categorised, the iconic image was displayed as a poster in a number of post-war exhibitions. And by these means the memories of returning soldiers were collectively constructed.

All of which is interesting and starts to explain why a non-existent image has entered the collective consciousness in the first place. But why did it persist, and for so long?

One reason that the book suggests is that pictures of a person looking directly at you while pointing their finger are very effective. Which is true. (There’s a good selection on the Wikipedia page on the poster if you want to test this theory out.) Which is probably why the U.S.A copied the Kitchener image for its own recruitment purposes in 1916.

Once this has happened, the two posters probably start feeding off each other. The Uncle Sam poster is, if anything, an even greater icon in America than the Kitchener poster is over here. It has been reproduced and parodied in an almost infinite number of ways since 1918, particularly where wars and governments are concerned.

Some of which, I am sure, travels over here and makes us remember our own iconic pointing finger in the form of Kitchener.

But there’s more to it than that. Because one of the interesting things about the Kitchener image is that it isn’t always there. Once all the soldiers have returned, and the patriotic lies of the propaganda have been dismissed, the poster seems to have been mostly forgotten about for a good forty-odd years. People have looked, but not found any visual references in the inter-war period and then for another decade or two after World War Two has ended.

So what happens to change this? The answer is the 1960s, or to be more precise 1963-4, when two specific things happen.

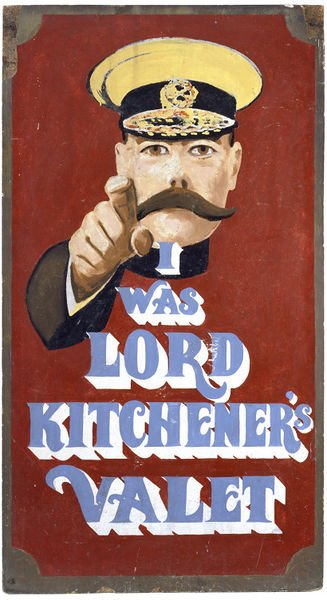

One is a boutique on Portobello Road.

This first shop was such a roaring success that they expanded to Carnaby Street and, later, the Kings Road, where the shop had the even better name of ‘I Was Lord Kitchener’s Thing’.

I have very nearly written this entire blog post just so that I can post that photo, but never mind.

But why, why Lord Kitchener? The answer, I think, lies in both the specifics of the early 1960s and the almost universal adolescent urge to get up your parents noses.

I’ve written about the early 1960s before. It’s the moment when the first generation comes of age who didn’t live through the war, not even a little tiny bit of it. They’re bored of hearing about the deprivations and the community spirit, they’re bored of self-sacrifice and drab. And most of all they are bored of hearing about the army. Because what does Lord Kitchener’s Valet sell at first? Surplus army uniforms.

And was this meant to irritate the grown-ups? Of course it was. A contemporary magazine article makes this clear.

Lord Kitchener of Khartoum would undoubtedly turn in his grave if he knew he was giving his name to a “with-it” boutique in London’s Portobello Road, and he would probably be even more horrified if he knew the boutique was selling the uniform of the British Army as the latest ‘mod’ gear.

The goading worked, too. In 1966 a ‘Muswell Hill youth’ received a conditional discharge after being stopped for wearing a Scots Guards tunic. But by then it was far too late: John Lennon, Eric Clapton and Mick Jagger all bought uniforms there and the red tunics and gold braid were everywhere. ‘I think it looked fashionable and smart,’ said Muswell Hill Youth, and it almost certainly did.

So the overwhelming urge to stick two fingers up at the British establishment, at their parents’ generation and the war is clear, but why did Lord Kitchener have to be brought into it all? Why wasn’t he old hat, so to speak?

The answer is, I think, that there was still a problem with attacking the Second World War, even for these bolshie youths. This was because those who had fought in World War Two had been very, very Right. They had vanquished Hitler, brought peace and prosperity, liberated the concentration camps. No one could argue with that. So instead the children of the 1960s had to skip back twenty five years, and pick their enemies from a much more equivocal war, where the generals had made mistakes, where little had been achieved and one in which those soldiers who had returned lamented the futility of the whole thing. In short, you wouldn’t dare say a word against Montgomery, not for a long time yet, and so it is Lord Kitchener instead who acts as proxy for that entire wartime generation.

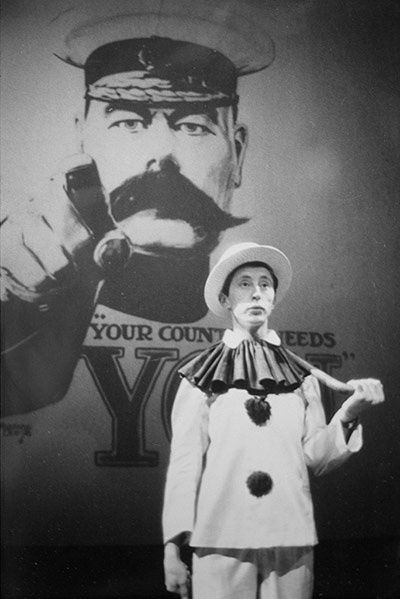

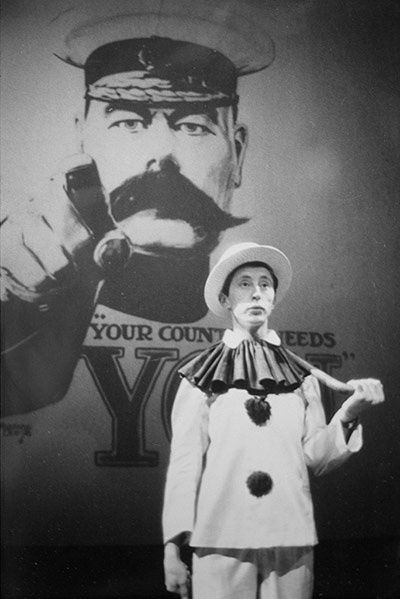

All of which makes even more sense in the light of the other early 1960s appearance of Kitchener. This was 1963, and it happens in Oh What A Lovely War! He was on stage.

And more importantly, he was all over the publicity and posters.

Joan Littlewood’s entire career sprang from the urge to go against established opinion. And by turning her fire on the army, this also allowed her to take aim at various other previously sacrosanct institutions like the Empire and the upper classes. But even for an iconoclast like her, picking a fight with the most recent war would have been a step too far. And so, once again, it is Lord Kitchener’s image, with all that this represents, which takes the flak.

By this point, the meaning of the poster has gone through several transformations. At first – for most people, there were of course always dissenters – this was a simple appeal from a national hero. After the war, returning soldiers revolted against the high-flown patriotic rhetoric that had brought them into the basest hell of the trenches, and the posters became a prime exhibit of how they had been lied to, Kitchener included.

But by the time it returns in the 1960s, the posters now stand for even more than this, representing upper class twittery and the follies of the gold-braided, Empire ruling establishment. For a long time, the poster gets parodied (and this is true of the American version too) when someone wants to point out that our rulers are taking us on the wrong path. This is true even today.

But now the image is so much part of our mental equipment that it can be used for almost anything. Including, it seems advertising storage. Which is where we came in.

This is such a complicated issue that I’ve left out lots of relevant things, including the repeated rise and fall of Kitchener’s own reputation. I’ve also been forced well out of my normal range, and so owe particular thanks to a couple of other internet sites, including this great post about I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet and this long but very expert discussion of the Kitchener poster. It’s also become clear that I would like to know a lot more about Joan Littlewood and the reception of Oh What A Lovely War! but then I have to stop somewhere, at least for now. So if you do have any thoughts to add to this, I’d love to hear them.