If I use the words Philip Larkin and 1963 in the same sentence, you pretty much know what’s coming next, don’t you?

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

(rest of the poem here if you want)

I suspect that part of the reason that Larkin’s thoughts are so often used, almost in danger of becoming a cliche, is that they express for us something that isn’t otherwise easily said. At some point in the early 1960s, there was not just a sexual revolution but a sea change across all of British culture. Virginia Woolf noted a similar moment fifty years before:

On or about December 1910, human character changed. I am not saying that one went out, as one might into a garden, and there saw that a rose had flowered, or that a hen had laid an egg. The change was not sudden and definite like that. But a change there was, nevertheless; and, since one must be arbitrary, let us date it about the year 1910.

What Larkin saw happening was the end of what you could call the ‘long 1950s’, which lasted from 1946 until, well, about 1963. For these seventeen years, Britain was still very much defined by being a country recovering from the Second World War, a country that wanted a fairer and more equal society, refrigerators for all, but most of all a nation that wanted a quiet, decent life. It’s no accident that this era lasted for seventeen years either, because what 1963 marks is the coming of age of the first children for whom the war wasn’t a defining experience. They didn’t need the reassurance of a quiet life after chaos, for the simple reason that all they had known was peace. The result, of course, was the 1960s.

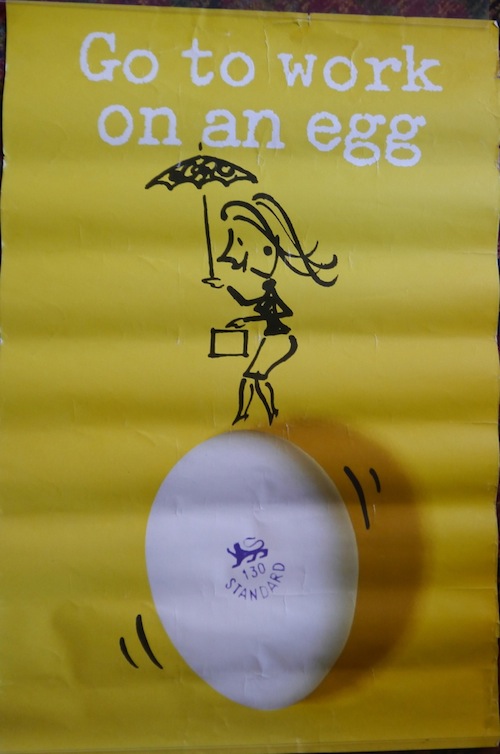

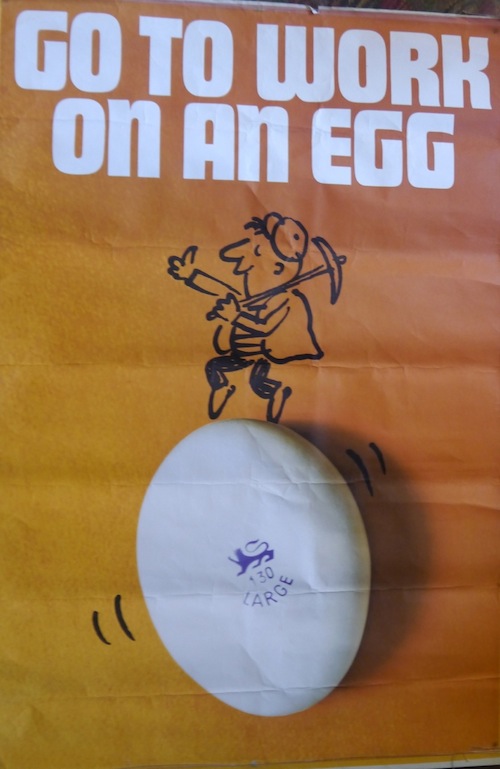

What provoked these thoughts, oddly enough, was the arrival of these posters at Crownfolio Towers.

With blessed thanks to eBay, which coughed the pair of them up at an entirely reasonable price.

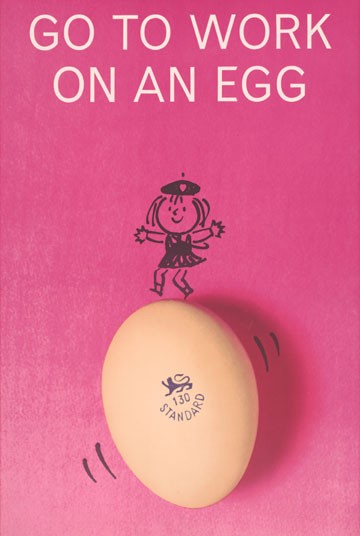

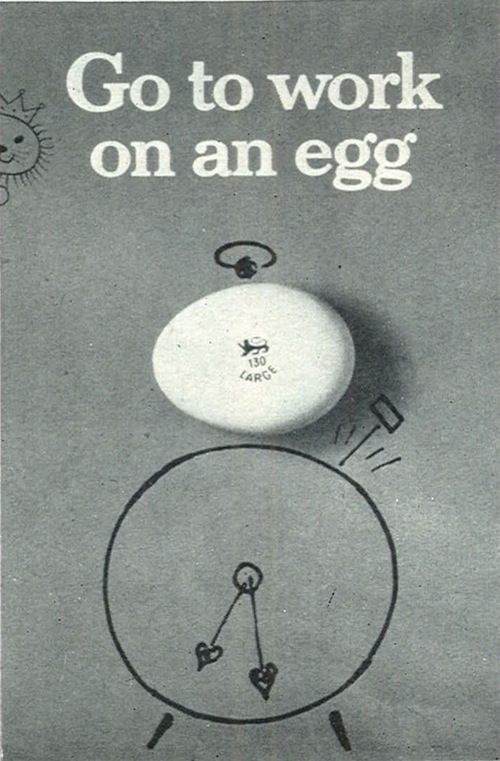

These are of course posters from one of the classic advertising campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s, ‘Go To Work on an Egg’, a campaign so famous that it has its own website. The campaign started in 1957 with television ads starring Tony Hancock but, as far as I can tell, these posters date from 1964-5. At least that’s when they were winning awards.

There are others too.

And of course there is a debate or controversy or whatever you will about whether Fay Weldon or Salman Rushdie invented the slogan. I can’t say I’m particularly fussed.

Because what’s interesting about these posters, at least for me, is that I would like to hang them on the wall. Which is unusual for posters of this period – and by this period I mean any time after 1963.

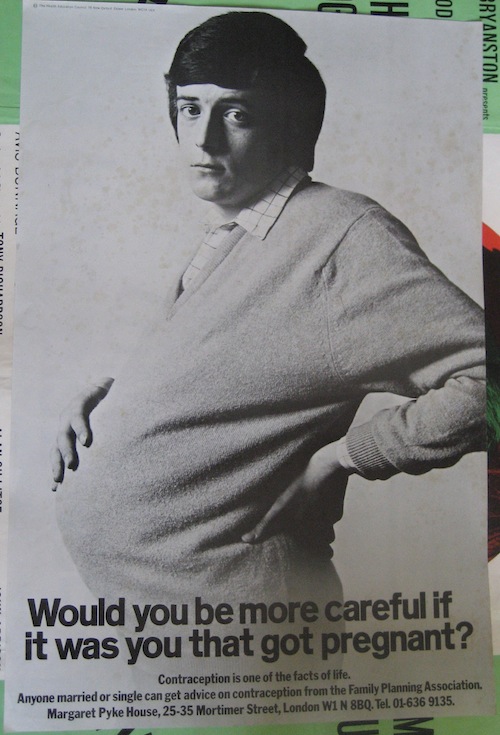

At various points in time we have bought ‘good’ – i.e. critically acclaimed – posters from after the 1950s, such as this Saatchi and Saatchi legend.

Or this protest poster by David Gentleman.

While I admire them, I can’t in truth say that I love them. And I most definitely don’t want to hang them on the wall.

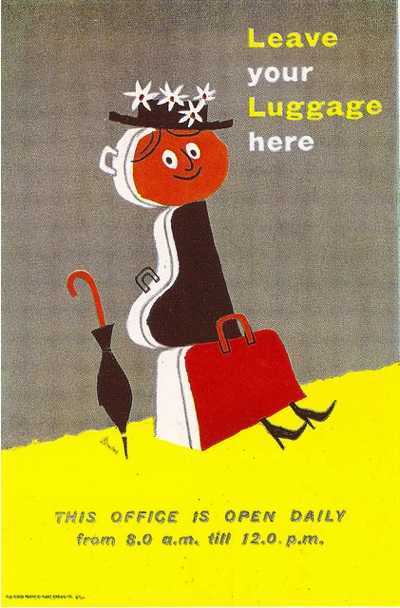

Whereas I can go through editions of Modern Publicity from the late 1950s and early 1960s and covet really quite a lot of what was on offer in there.

So what changes at the end of the long 1950s?

A proportion of it is down to simple practicalities, most importantly the rise of television means that people are spending less energy and creativity on posters. It’s possible that this also means that posters have to try a bit harder to get noticed, hence the increased use of shock tactics.

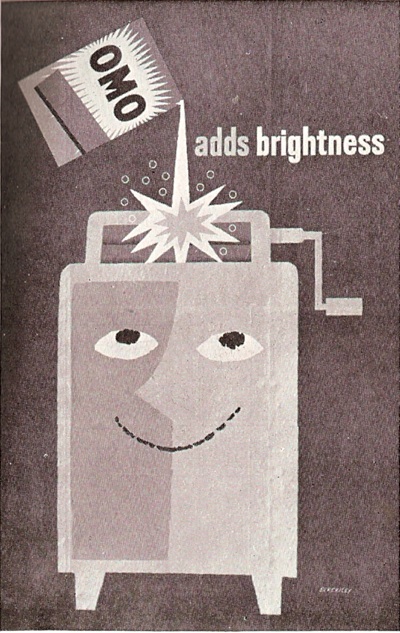

But I’d also argue that there is a much deeper change in what we might call the mood of poster designs. As demonstrated by that Tom Eckersley Omo poster above, the 1950s is the decade of the grin.

I’ve written about this in the context of Tom Eckersley before, about how it’s very easy to dismiss these posters as child-like and simplistic when actually they are the result of much more complex emotions, of relief at the end of the war and a resultant ability to take pleasure in very simple things. It’s also worth noting that if I’d had a washing machine in 1962, I’d be pretty chuffed too.

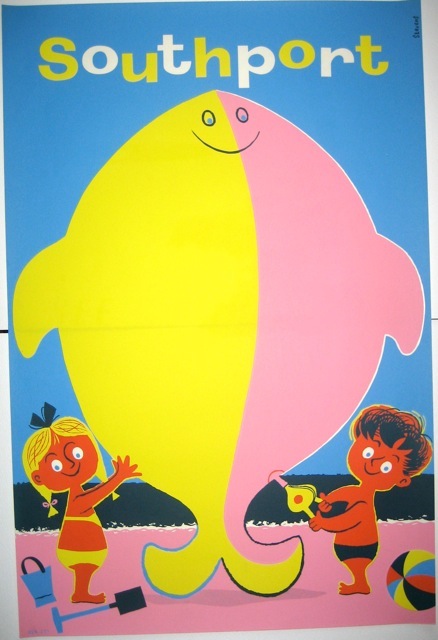

And of course Eckersley by no means had a monopoly on the grin. Here’s Harry Stevens at it as well.

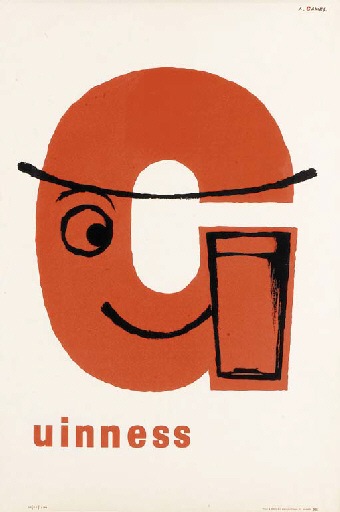

And it forms the basis of one of Abram Games’ most famous posters.

I could go on.

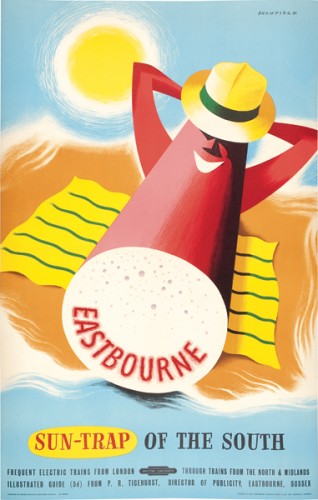

And on.

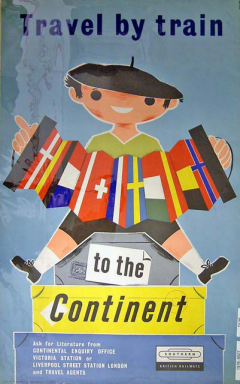

And on.

As I tried to point out in the Eckersley post mentioned above, this is may look like a simple, child-like joy, but it is nothing of the sort. It’s much more complex and adult than that, stemming from the chance to savour the simple pleasures of life – train trips to the continent, a pint of Guinness, a washing machine – which are all the more appreciated after the dislocatons and horrors of the war.

This is the simple joy of a late Matisse painting.

Or of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence. (I was forced to read these as a snarky seventeen-year -old for my A-Levels, with the entirely predictable result that I thought these were a set of feeble-minded rhymes about lambs skipping and that the grown ups clearly had no taste. It’s only now, as a grown-up, that I can see Blake’s point at all.)

But when a new generation arrives, a generation which has not passed through any of the hardships of war, this subtle emotion can’t survive any more. So it’s out with the old, goodbye to the grins and the taking pleasure in life, and in with shock tactics, subversion and generally getting a rise out of the grown ups, something which could only be done if you had no idea what they went through. And while the results are often admirable, I don’t often want to hang them on the wall.