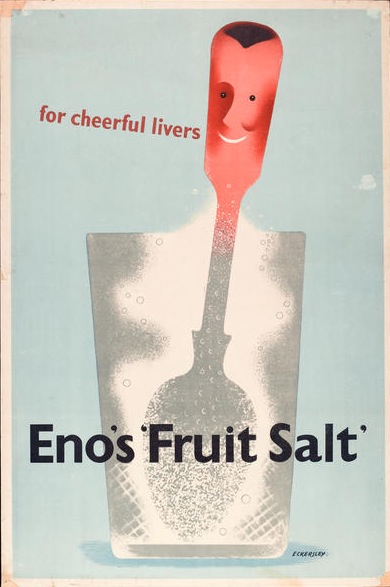

I’ve always loved the smiliness of Tom Eckersley’s posters.

Hastings, n/d

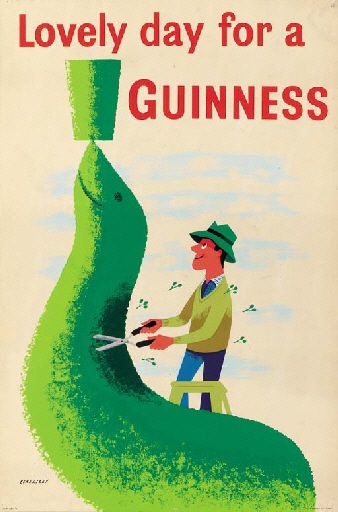

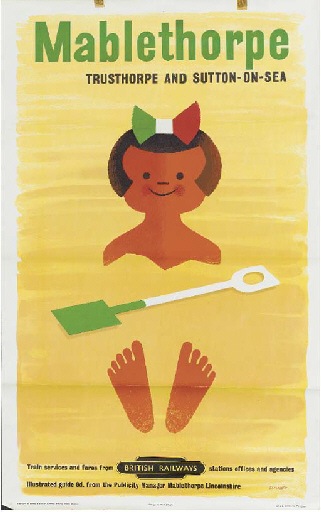

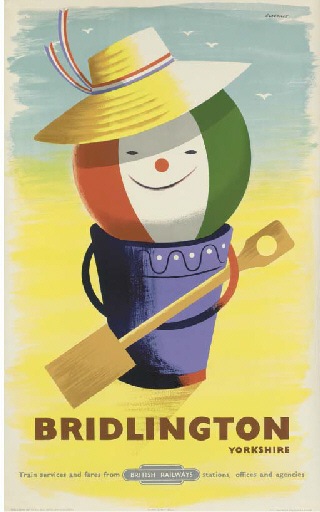

Between the late forties and the mid 1950s, his work is filled with cheerful characters, from spoons to beach balls.

Bridlington, British Railways, 1955

And of course people.

So I was rather disappointed to discover that Eckersley himself didn’t like these posters later on in his life – he said that he wanted to get rid of the whimsy and the smiling faces as they almost made him angry. Which seems a harsh judgement on something so delightful.

Then, a couple of months ago, I read an interview with the poet Jo Shapcott, in which she discussed her experience of having cancer.

I ask whether that period changed her sense of the world. She says it did, dramatically. “When Dennis Potter was dying, he filmed that famous interview, in which he talked about looking out of the window, and observing the blossominess of the blossoms with an increased urgency and joy. And I think that does happen to cancer survivors – apparently it’s really common to feel euphoria[.]

But it was her final words which really struck me – and, strangely enough reminded me of all of the posters above.

Does she still feel the euphoria she did at the end of treatment? “I do,” she says. “All these years later, it hasn’t gone away.”

Because perhaps we – and also Tom Eckersley himself – have been doing the 1950s a disservice.

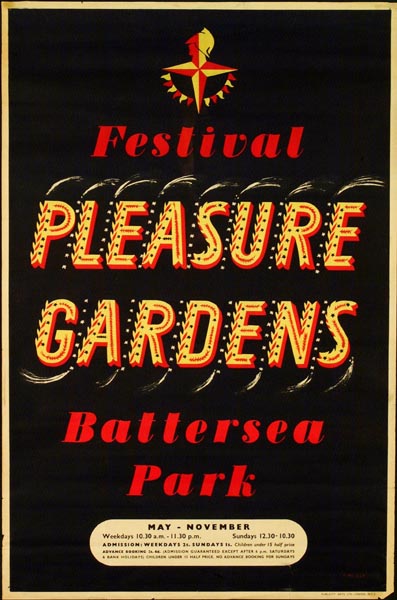

It’s really easy to characterise the early 1950s as an era which was almost feeble-witted. See the women gladly strap on their floral pinnies and get back into the kitchen while the men take their pipes, sow the vegetable garden and tidy out the shed. Imagine their pleasure in a brand new fridge or washing machine. Look at their simple-minded delight in the primary colours and pretty shapes of the Festival of Britain or happy posters with smiles on.

All of which is rather patronising, and, I think, wrong.

Because these are not a new generation of air-heads but the people who have lived through six years of war. For the first time it’s not only the men on active service who’ve faced death every day, but the women and children, the clerks and the old men too; they have all spent years in which they knew that they might not make it through to the next morning. Having lived with death breathing down their necks for so long, might they not feel euphoria too once it has departed?

They weren’t being dim when they they enjoyed the simple pleasures of their home, or the visual delights of the Festival of Britain. Rather than a child-like wonder, it was the more c0mplex pleasures of people who have been through the fires and survived. Perhaps, in fact, they were both more clever and more alive than we are now?

To be fair to Tom Eckersley, he himself partly knew this. Because he also said of these posters that they were done sincerely. It was just that he couldn’t ever do them again. Maybe, in the end, the euphoria does fade after all.