Skylon Biro

Mr Crownfolio went off to do some shopping for our holiday the other day. He still has no sunhat, but we do now own this.

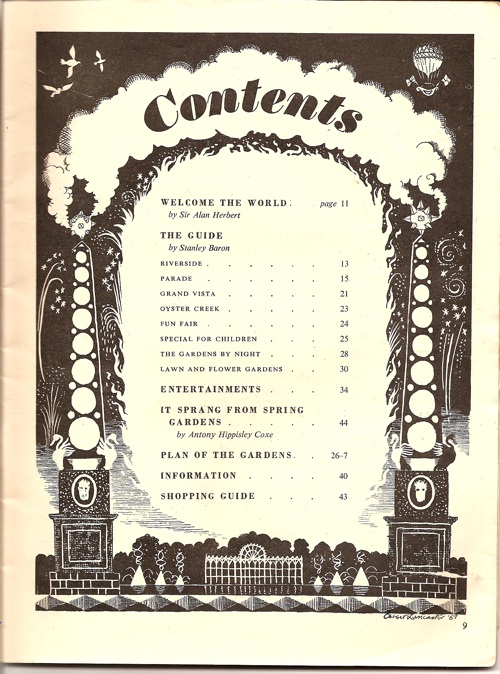

Given that the gardens were the slightly more raucous and, dare I say it, downmarket outpost of the Festival of Britain, I wasn’t expecting too much from the guide. But it’s a surprisingly interesting piece of design; take this contents page by Osbert Lancaster.

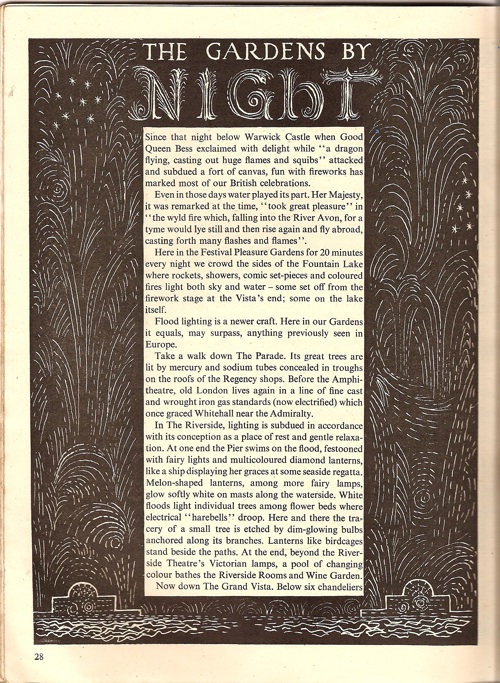

There are also some interesting layouts too.

Although I will spare you the rest of the poem which isn’t up to the standard of the typography.

The good design perhaps isn’t so surprising, as it turns out that one of the two editors and designers of the guide is Ruari McLean, founder of Motif, amongst other things.

He clearly commissioned some good artists but very few of the illustrations are credited – not just the full page spreads, but also the smaller black and white illustrations, in a whole range of styles, which are scattered throughout the text.

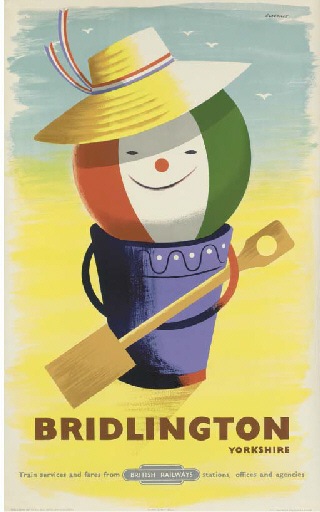

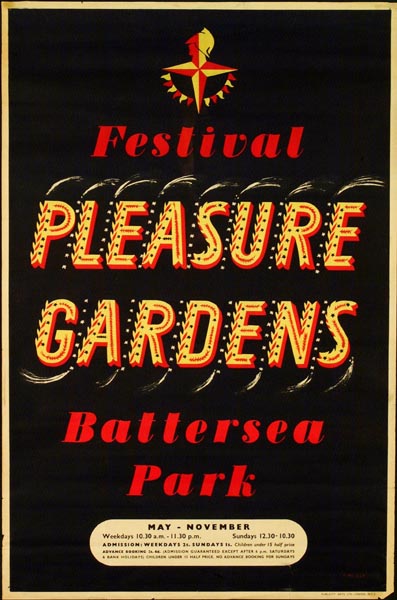

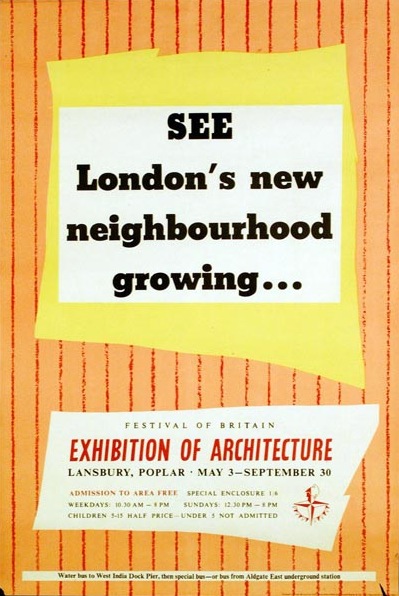

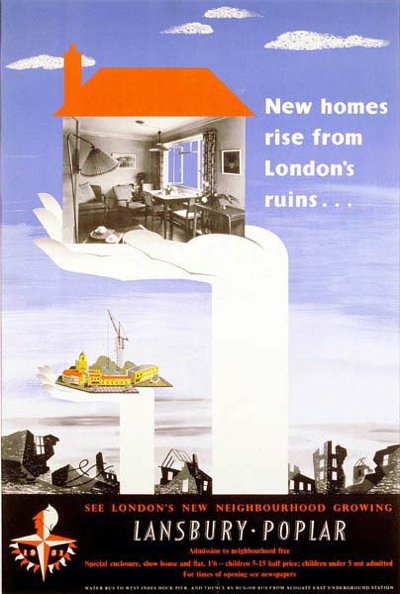

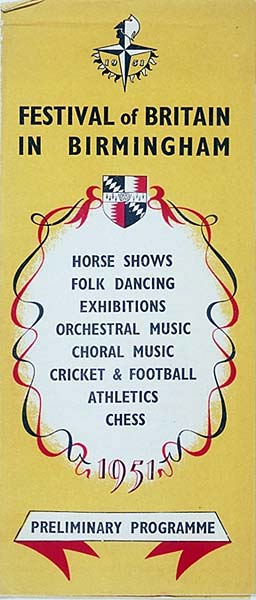

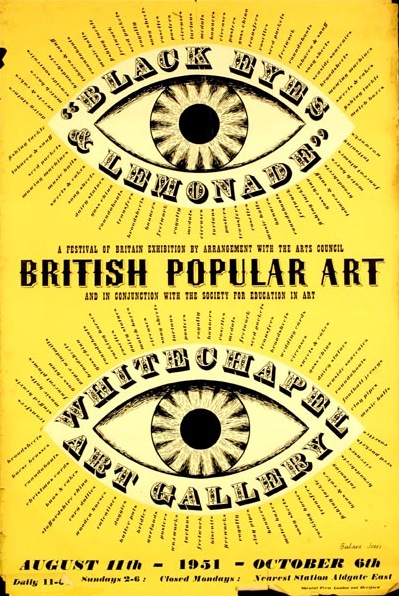

This is all part of trying to make the Battersea Pleasure Gardens (its name alluding to the old eighteenth century pleasure gardens at Ranleagh and Vauxhall) as uplifting and high-minded as the rest of the Festival. The guide makes it sound like a promenade of flowers, architecture, Punch and Judy Shows and orchestral music. The pictures, however, show that it was basically a very large funfair.

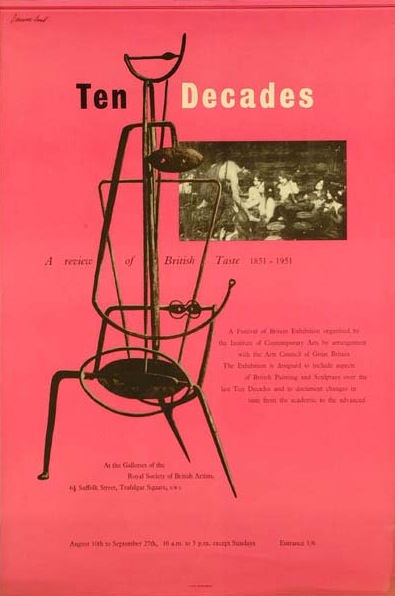

In the course of finding out all of this, I read an article which suggested that the Festival of Britain could be seen – if Battersea and the South Bank are thought of together – as the world’s first theme park, with the theme of course being Britain. It’s an interesting thought.

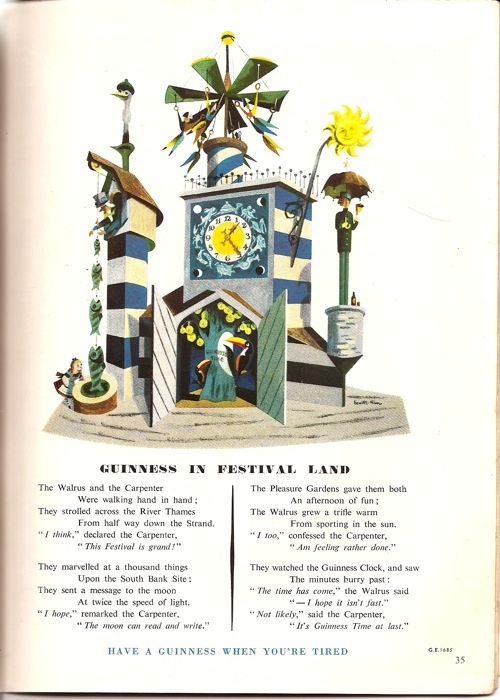

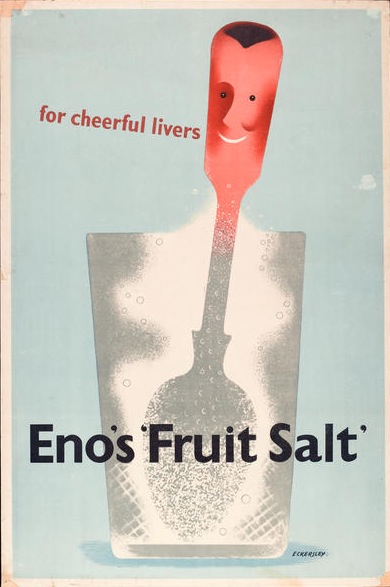

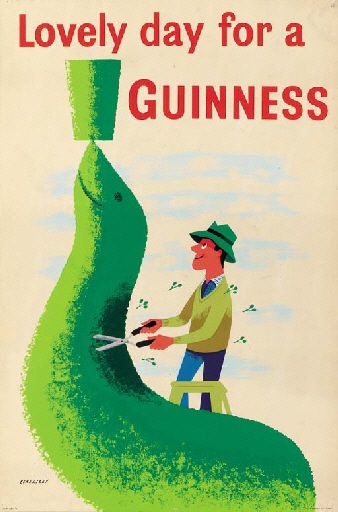

But I haven’t quite finished with the guide yet, because it’s also got some interesting advertisements in. One is by our old friends Lewitt-Him.

They designed the Festival Clock, which was one of the attractions of Battersea and apparently contained the most complicated clock mechanism ever built at that time. It was such a success that Guinness commissioned eight more, allowing the clock to tour department stores and amusement parks all over the country.

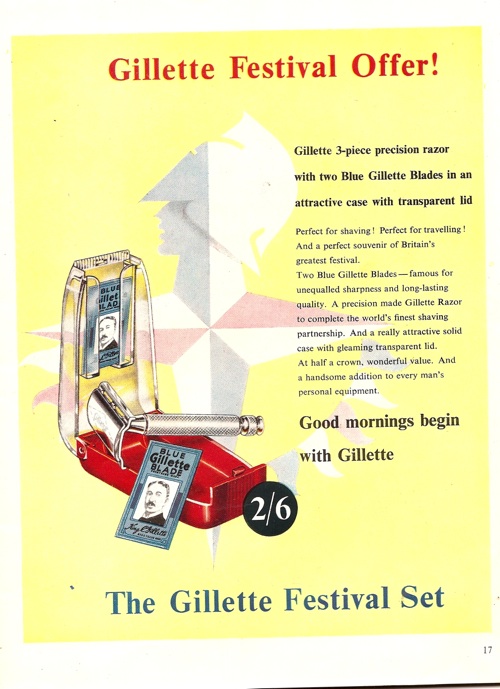

This Gillette advert, meanwhile, is a reminder that modern design still only had a very tenuous hold in 1951 Britain, and certainly hadn’t spread to packaging design.

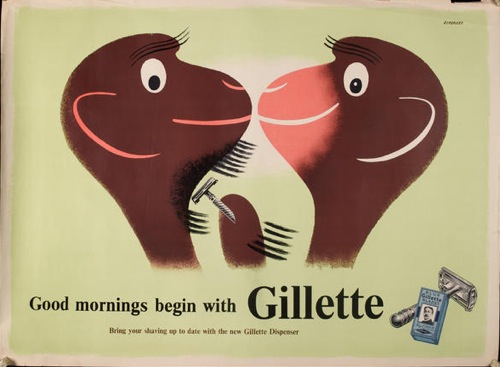

Tom Eckersley’s Gillette posters from a year or so before suffered from just the same problems of contrast.

A copy of this hangs on our stairs and, every so often, I am still shocked again by the contrast between the modern image and the Victorian packaging.

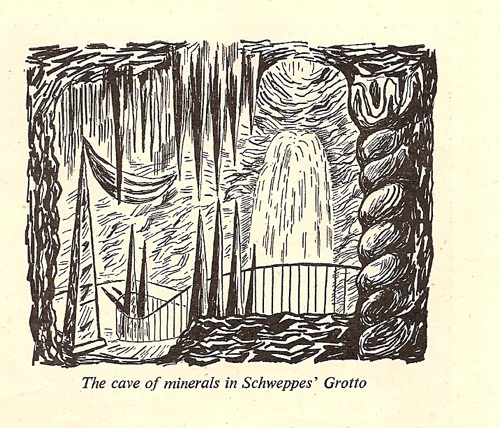

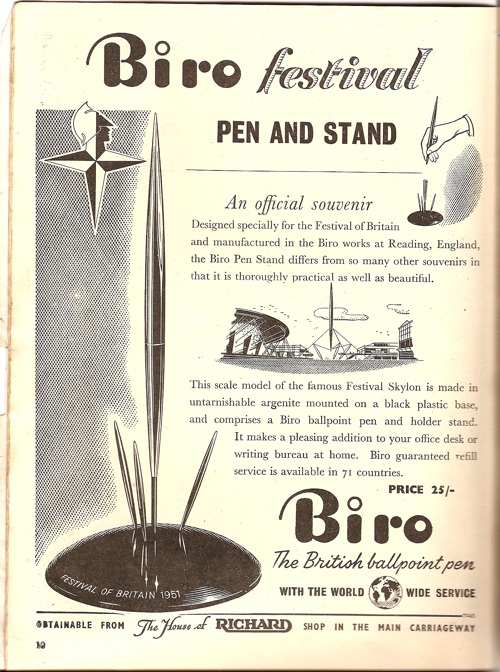

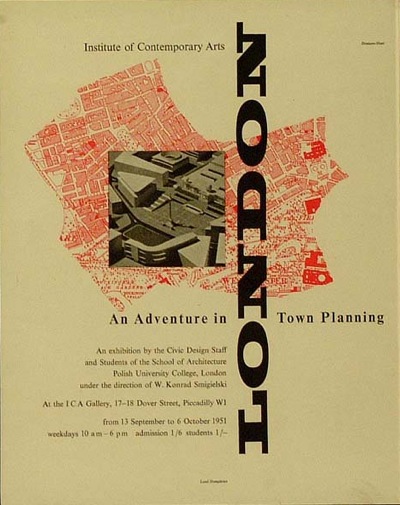

Finally, though, there is this, which will just have to describe itself.

Truly it is a brave new world which has such things in it.