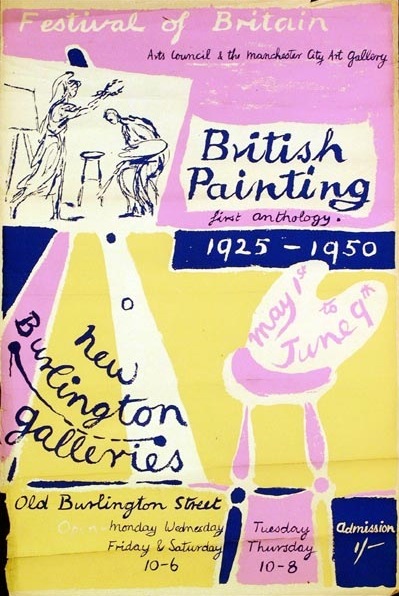

Mr Crownfolio has been fossicking in the furthest depths of the internet again. And he’s found this.

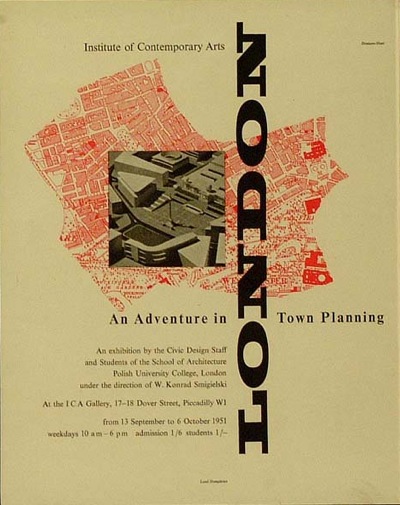

And this.

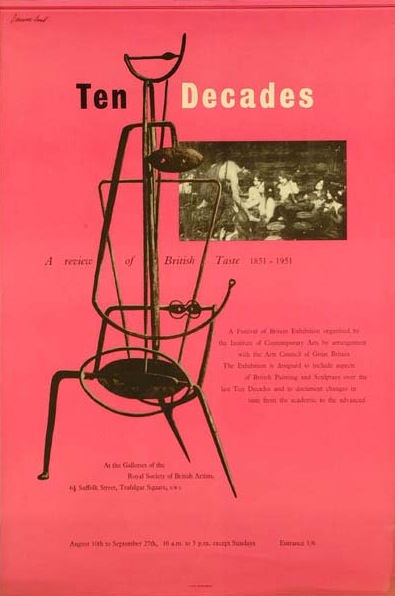

As well as this.

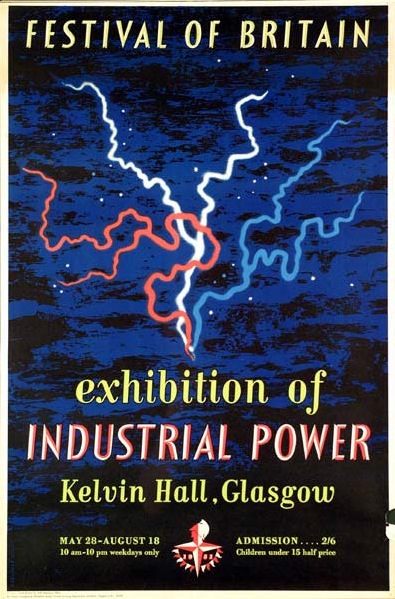

What links them all is this.

The Festival of Britain. Or, to be more precise, the Museum of London’s rather wonderful Festival of Britain online exhibition and archive. Not only does it have photos and reminiscences, it also has a searchable catalogue stuffed to the gills with wonderful posters and other ephemera.

Now I fell in love with the Festival of Britain when still in primary school, I have a vivid memory of the Radio Times doing a feature on the Festival in 1976, on its 25th anniversary, and wishing that I could have walked around in all of that primary coloured optimism myself. It looked a great deal more fun than the 1970s.

This was clearly a formative experience, too, leading to a whole mis-spent life of 1950s collecting, a thesis, and, in the end, here. The Radio Times has a lot to answer for.

If only I’d had all of this wonderful material to play with then. The Museum of London’s archive is a result of a gift from Peter Kneebone, who combined being a key player in the Festival Office with being a keen epehemera collector. Perfect.

There are some great things in there. Mr Crownfolio says he has seen this Abram Games before, but I’m not sure that I have.

Or you might want to consider this Reginald Mount.

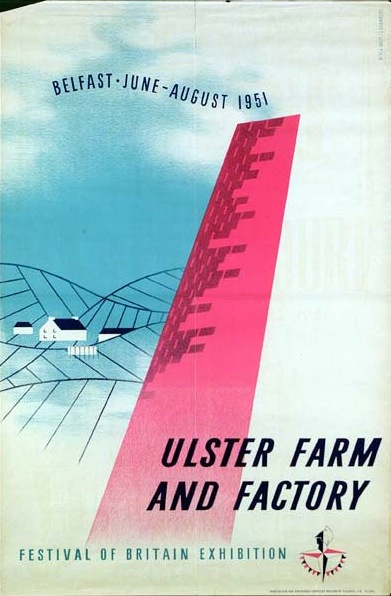

What’s particularly interesting about what Peter Kneebone collected is that it doesn’t always conform to our images of the Festival, which can tend to be stereotypical, generally involving the South Bank and the Skylon, possibly also the Festival Hall if you’re lucky. The Reginald Mount poster above is a reminder that exhibitions and events were occurring all over the United Kingdom. In Ulster, you could find out about Farm and Factory as well.

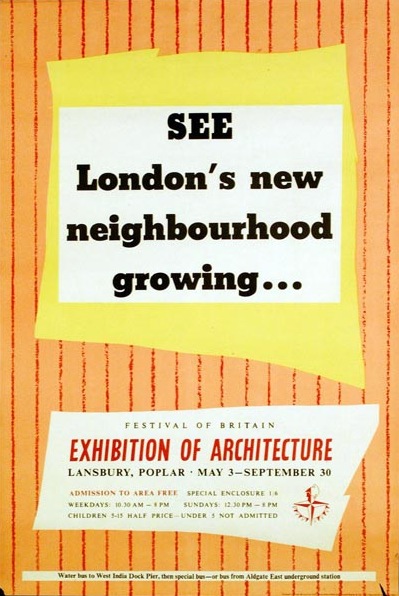

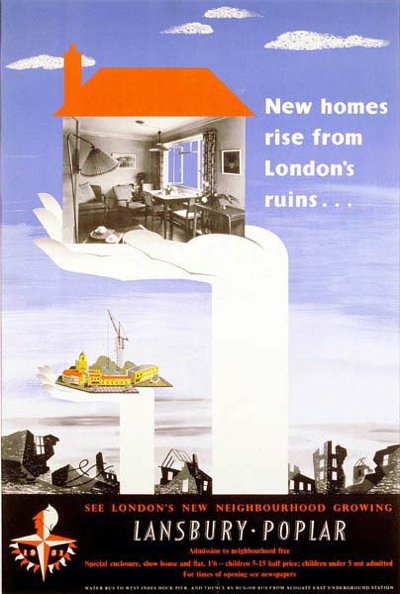

Furthermore, not all of the Festival disappeared in a puff of smoke at the end of 1951. This ‘Living Architecture Exhibition’ (proof that Grand Designs Live is not a new idea in the slightest),

became the Lansbury Estate, which is still there.

The images are also a reminder that, without hindsight, the Festival wasn’t the victory for soft Scandinavian modernism that it now seems to be. Quite a few designers are harking back to the Great Exhibition of 1851 as much as they were looking forward.

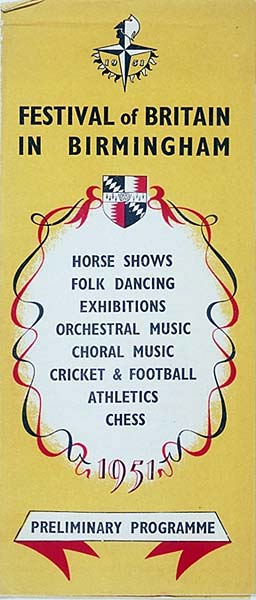

In this case, Eric Fraser, producing a generic poster to be used across Britain. Some of the designs seem to refer even further back to the Regency, like this Birmingham leaflet

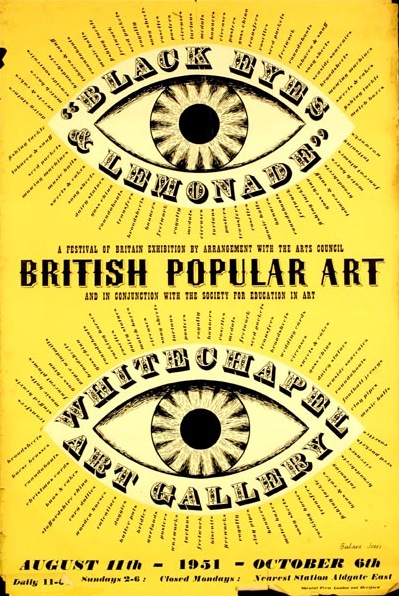

A vein of British eccentricity and folk art also ran through the whole Festival; corn dollies and unicorns lurked within the modern buildings of the South Bank and elsewhere. Here’s the incomparable Barbara Jones (about whom I will write one of these days), whose poster combines both Victoriana and whimsy.

What’s also great about the archive is the display; these are real, slightly battered pieces of ephemera, rather than air-brushed scans. It’s good. (And also reassuring given the condition of most of what we own.)

My only gripe would be that not enough designers are named. I’m pretty sure that the Ulster Farm and Factory poster is by Willy de Majo, who designed the whole exhibition, but the Ten Decades poster has a signature that I just can’t read, or find anywhere else, and it would have been good to know. But that’s my only, tiny quibble, so hurrah for the Museum of London, Peter Kneebone and their lovely archive.

I love Barbara Jones. The exhibition that accompanied the poster above looked fascinating. Folksonomy writ large.

Her stuff is so distinctive, isn’t it. We’ve only got a few odds and ends of her work, sadly

That Barbara Jones ‘British Popular Art’ poster is wonderful, it has poster power with detailed placement, I think it’s an important piece and yet very rarely seen in anthologies of the fifties graphic movement.

I agree. I think that, as with the Festival itself, it doesn’t fit with the narrative of the decade.

But it does show just how important digitising all of these archives are; now that so much material is available online, people can make their own judgements about what’s important and what’s not.