I’ve had Paul Rennie’s Modern British Posters: Art, Design & Communication for a few weeks now, and am guiltily aware that I haven’t given it a proper mention yet. Now there are a whole heap of real life reasons why this hasn’t happened, which I won’t go on about, but I am also aware that I’m finding it hard to come to a conclusion about it. Which is absurd, so here are a few thoughts which may or may not come to a definite answer at the end.

Tom Eckersley, Seven Seas Vitamin Oil, 1947

This doesn’t mean that I don’t like it. The book is beautiful and would justify its cover price (more on that below) for the illustrations alone. You’ve seen a few on the blog already, there are plenty more littering this post. There simply isn’t another book covering these subjects in this detail and with this kind of wonderful reproduction, so it’s a great thing to have.

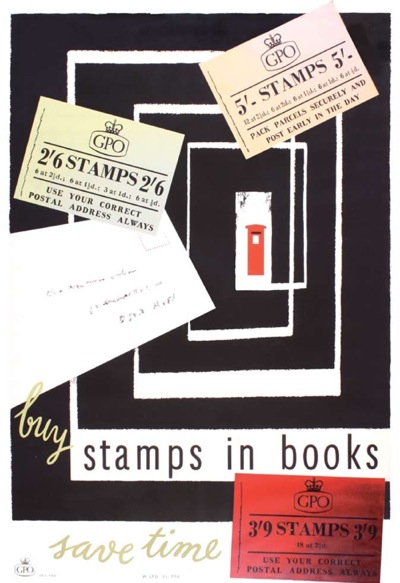

HA Rothholz, Stamps in Books, GPO, 1955

Even better, the book mentions Quad Royal which is very flattering indeed. So now it’s been immortalised in print, I’d better keep this thing going for a while, rather than just be a fly-by-night blog.

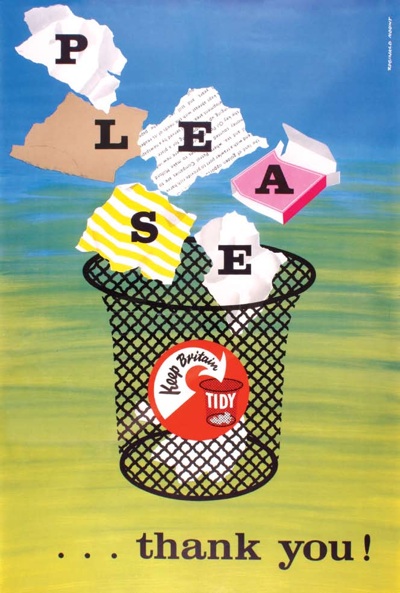

Reginald Mount, Keep Britain Tidy, 1950s

But as well as the book being a whole treasure trove of beautiful images, Paul Rennie also makes some really good points about posters and collecting, so much so that I am going to repeat them all over again here. At the start, he observes that part of the reason that no one else has written this book before him is that the world of the poster, in Britain at least, is absurdly fragmented.

For example, railway posters, motoring posters and war propaganda all form specialised archives within separate institutions. Within the context of these distinct institutions, there is no urgent requirement to integrate the various and disparate parts into a history of visual communication.

I’ve touched on this in posts before – this odd disjunction between disciplines results in quirks like the National Railway Museum not thinking about its posters in terms of designers on their website and many other odd occurrences. People who know all about railway posters might have no idea about the history of the Ministry of Information; the Imperial War Museum has no reason to care about what designers did before or after the war. As a result, Modern British Posters is therefore pretty much the first decent survey of the whole, and that can only be applauded.

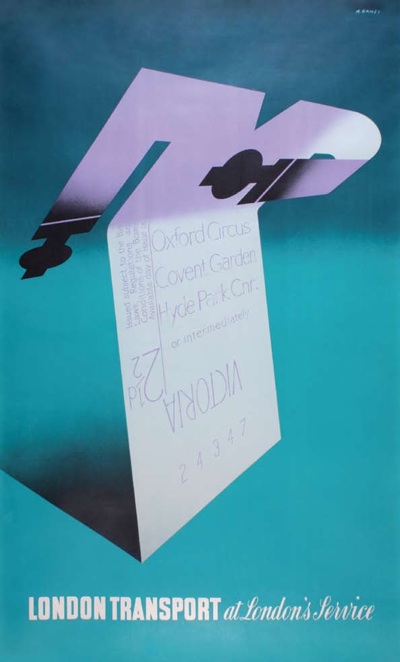

Abram Games, At London’s Service, London Transport, 1947

I’m also really interested when, at the end of the book, he sets out the history of how they started collecting, and the rationale behind what they chose to buy. Partly because he started out by being fascinated by the Festival of Britain and then, in discovering more about Abram Games and the Festival symbol, found himself intrigued by a wider world of graphics and communication. I trod exactly the same path too (I still have the little Festival badge that I used to wear on my hat as a teenager); it makes me wonder how many people have followed the same thoughts, and also why the Festival exerts such a potent hold over our imaginations even now.

Abram Games, See Britain By Train, British Railways 1951.

But he also explains why they bought what they did.

Our collecting began, back in about 1982, with an interest in modern design… In 1982, the words British and Modernism seemed like a contradiction in terms.

The direction of our collecting was formed in relation to this widespread,and misguided, perception of British resistance to modernity. Conveniently, it turned out that British items were generally of little interest to international collectors and were, accordingly, less expensive to purchase.

In a way, I wish he’d put this manifesto right at the start of the book, because it’s really important. This is partly because this is – and Paul Rennie freely acknowledges the point himself – a very partial book. Every single illustration is from their own collection and so knowing the history behind it makes a big difference to the way you might read the book as a whole. (I have been trying to work out whether there is a similar unifying idea behind our own collecting; so far I have only managed to come up with: It was cheap and we liked it).

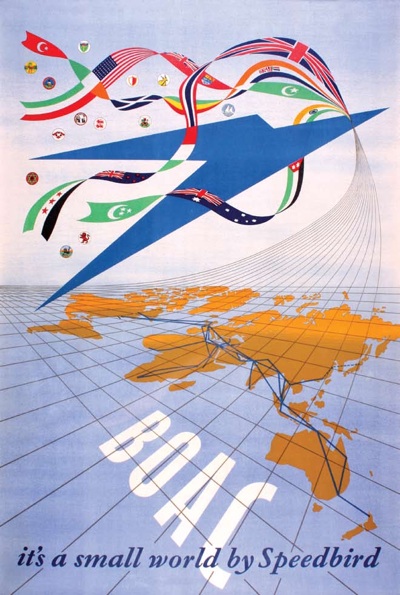

Henrion, BOAC Speedbird, 1947

The idea of the British relation to modernism itself is really interesting, and something I’d want to think about at length and probably devote a whole blog post (0r three) to. But it also informs a lot of the arguments that he’s making in the main bulk of the book, so it would have been good to know beforehand.

Now, I have to confess that between these two ideas I did get a bit lost in the middle of the book. Now this is partly I think a problem of the form – Paul Rennie is heroically attempting a complete survey not only of the history of posters in Britain, but also of the social and economic conditions which affected how they were produced. So it is, of necessity, a bit of a race through quite a lot of ideas and thoughts.

But also – and this is the bit I have been pondering for a while – Modern British Posters is at heart an academic book. It’s having a dialogue with a lot of other books, and theories of art and design, ideas about cultural production and the transmission of modernism, and that simply isn’t a conversation that I am part of any more. Academia and I gave up on each other more than twenty years ago, and since then I have been concentrating on the much simpler task of telling stories about people and things. So the fault is probably with me rather than the book, for which I can only apologise. I’d be interested to hear what anyone else thinks about this, particularly if you’re a design historian and have read it.

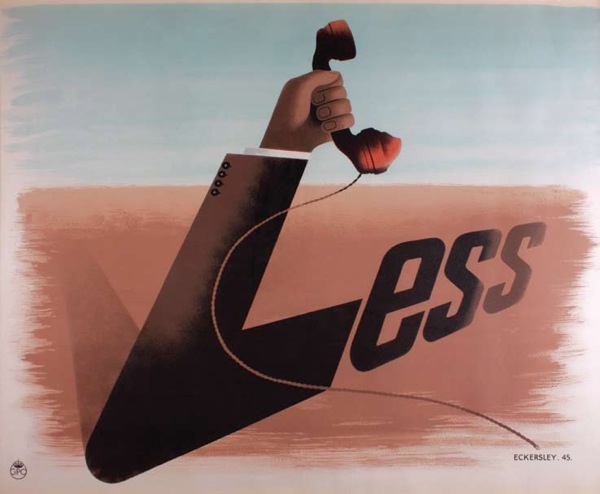

Tom Eckersley, Telephone Less, GPO, 1945

If you haven’t read it yet, and want to have an opinion, which of course you do, I am pleased to say that there is also a special Quad Royal readers’ offer (we’ve never had one of those before, get us). The book is available at a massive 40% off the list price to you our esteemed reader. To get hold of it, just email jess at blackdogonline.com, with Quad Royal Readers Offer as the subject line, and she will sort out the rest.