“It may be clever and modern and progressive. But it certainly isn’t English.”

That’s the incomparable Patrick Wright quoting from a ‘heritage journal’ called This England. He’s talking about landscape and memory, but it struck a chord with me.

Because ever since I wrote about Paul Rennie’s Modern British Posters, I’ve been thinking about the relationship between modernism and British design. It’s a very important undercurrent in the book, but one that he only spells out at the end.

Our collecting began, back in about 1982, with an interest in modern design. We discovered that, where the market existed, it was conceptualised around an idea of modernism as an international phenomenon of people, ideas and products that connected Moscow, Berlin, Paris and New York. In 1982, the words British and Modernism seemed like a contradiction in terms… Our interest in graphic design quickly began to define itself as an attempt to gather together irrefutable material evidence of British Modernism.

So in essence, the whole book – and of course the Rennies’ whole collection of posters around which it is based – is didactic. His argument is for the existence of a specifically British approach to modernism, from early McKnight Kauffer to late Eckersley.

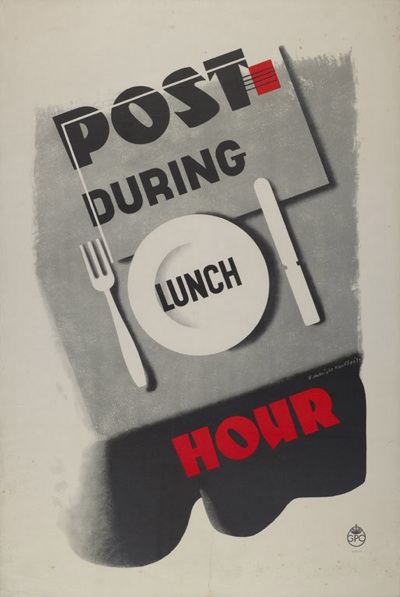

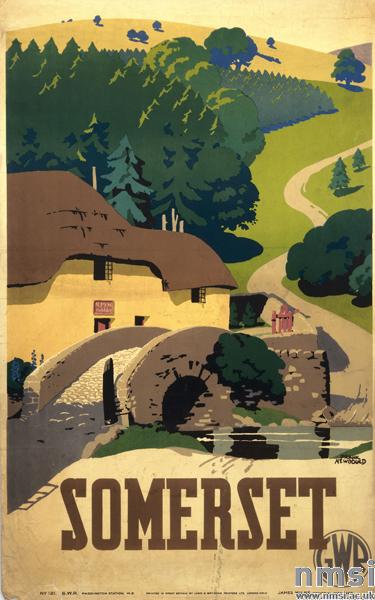

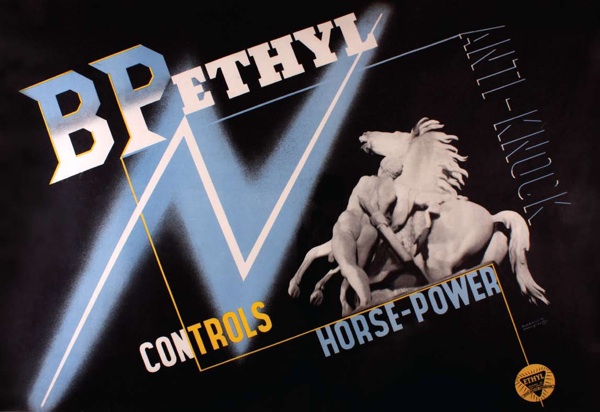

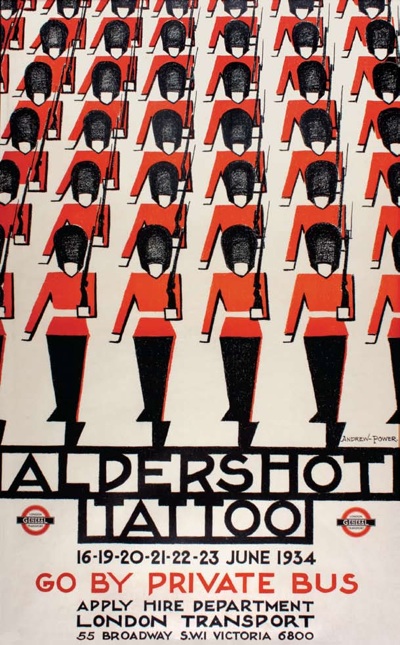

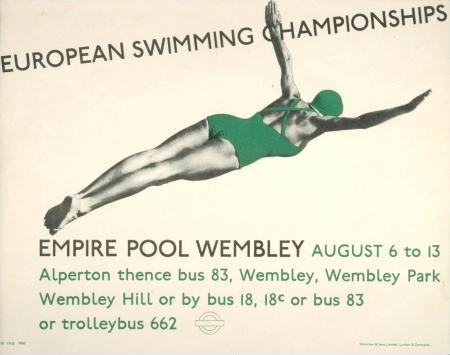

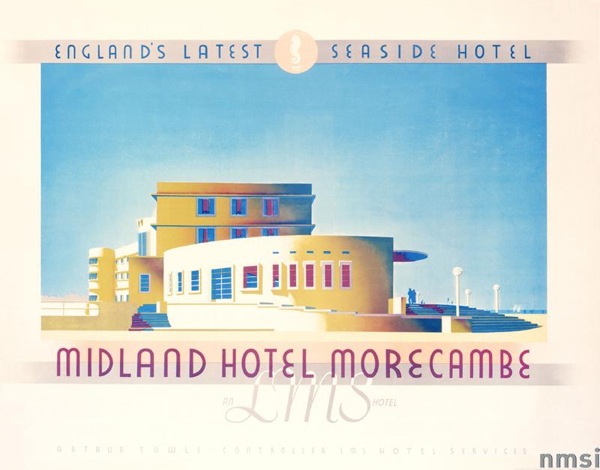

There can be no doubt that this home-grown kind of modernism existed; the evidence is there in the shape of posters like these (Powers, 1934 and anon, 1938) and many, many more. Just take a look at the book.

Rennie is in good company when he wants to place Britain within the modernist tradition, as it’s a path that many other writers have taken before him. Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design has exactly the same aim. Here the argument is that Voysey, Owen Jones and even William Morris are the fore-runners of German architectural, steel and glass, functional modernism.

But Rennie and Pevsner have more in common than just that. They position themselves as swimming against the tide, having to make an argument for a kind of modernism which isn’t seen as naturally British. (In the case of posters, it isn’t very British anyway; emigree designers must outnumber the home-grown modernists by at least three to one, but that’s another story for another day).

Edward McKnight Kauffer, GPO, 1937

This isn’t a view that only applies to buildings or posters, either. It’s been said that Utility furniture scheme during World War Two and after was a chance for modernism to be imposed on the unsuspecting British public, who weren’t showing much inclination to embrace it any other way. It’s also possible to argue (as I have before) that much modernism in posters operates in the same way. During the 1930s institutions such as the GPO, London Transport and Shell commissioned modern design in a seemingly medicinal fashion, because it was Good For the general public.

Graham Sutherland

I’m intrigued most, though, by what’s implicit here. If modernism is seen as improving, then what is it trying to make better? If modern design is being imposed on mainstream taste, then what is this style that it’s fighting against? Can we say what exactly is this natural British design?

Strangely, the answers to these questions aren’t as easy to find out as you might imagine. Design history tends, even now, to think in terms of the narrative of modernism alone. It’s a clean-lined and minimalist version of the Whig view of history, in which everything leads towards the ultimate fulfillment of civilisation, which can only be some monochrome combination of Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus and Helvetica Neue standing triumphant over the death of ornament. All of which tends to create some oddities in the stories they tell.

One is a kind of tortured argument, as designs and designers are jemmied into place to fit the party line. Tim Mowl (a man who knows; his book Stylistic Cold Wars: Betjeman Versus Pevsner is worth quite a lot of your time, if not the £69.99 that someone wants for it on Amazon) calls Pevsner’s attempts to turn William Morris into a proto-modernist “obvious nonsense”. Harsh, but fair.

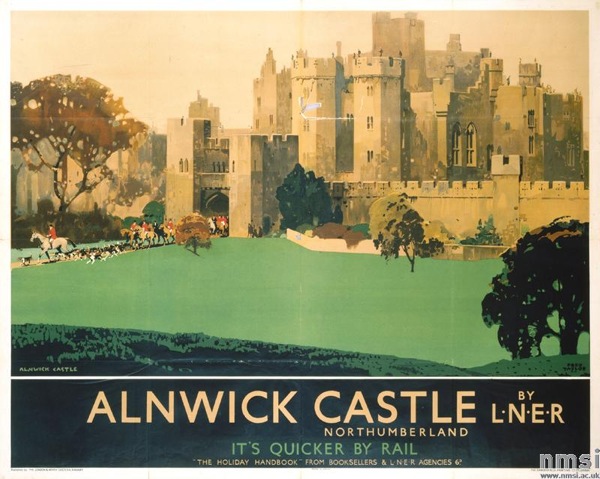

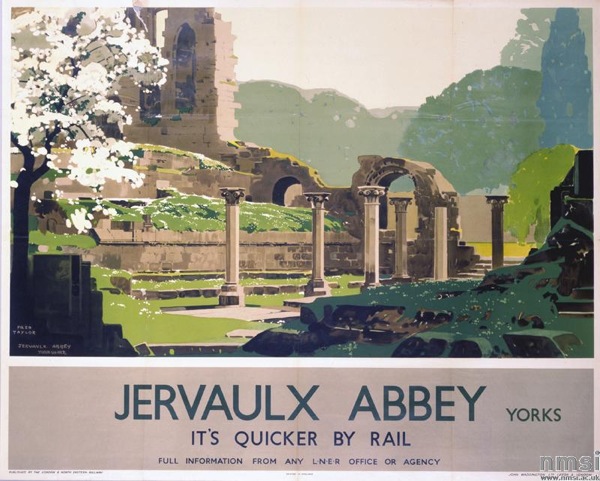

Modern British Posters isn’t having to strain so hard, as the designs were there. But, in Britain, if you only write about the modernist experience, quite a few designers and posters don’t make the cut. Like railway posters, for example.

Fred Taylor, 1933

Because this is the other problem with surveying the material world only through the lens of modernism, particularly in Britain. The vast majority of objects don’t get seen. If you wanted to find out what furniture people who didn’t care for the Bloomsbury Set and pale wood were buying just before the war, or how the average, non-Arts-and-Crafts Victorian papered their walls, you’d be hard pressed to find out. The books won’t tell you and nor, in the main, will the museums either (The Geffrye Museum is a notable democratic exception here).

It’s not even as though these things are criticised, or even described. They are invisible, utterly absent from the story.

Yet such objects did exist, in their hundreds and thousands, these wing-back chairs and flock wallpapers, these Crown Derby dinner sets and aspidistra stands. Which takes us back to the question I asked earlier. Exactly what is ordinary British taste if it isn’t modern? And if we don’t know, how can we find out?

These questions aren’t here just to be difficult (although of course that is part of the fun). I’m also raising them because, perhaps, posters can give us some clues.

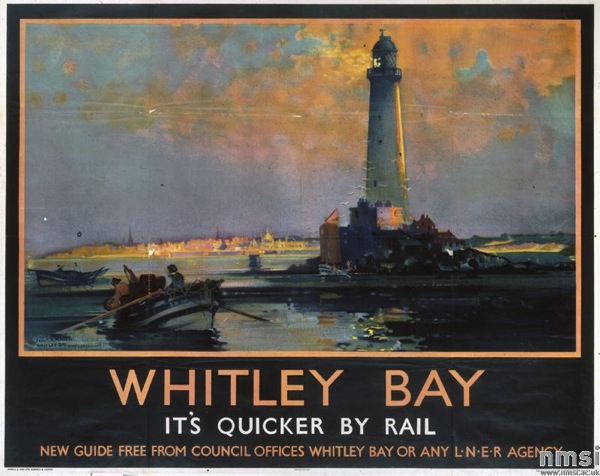

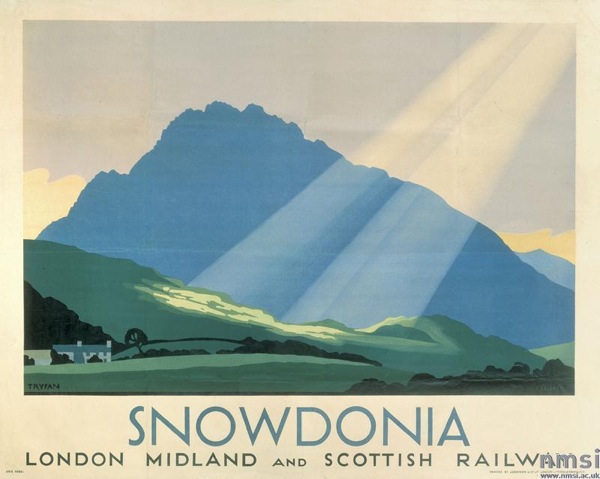

After all, not all graphic design flew the modernist flag. In the same year that McKnight Kauffer produced his machine age version of BP petrol above, 1933, there were other styles and other designers at work too. I’ve raided the National Railway Museum’s collection to find a selection from the same year.

Some of them are modernism incarnate.

While others act like it had never happened at all.

Frank Mason

Meanwhile yet more are modern, but at the same time not modernist.

Charles H Baker

This view is about as far from a celebration of steel, movement and urban frenzy as it is possible to get. But at the same time it is still modern. Go figure.

There are many many more too, from Fred Taylor to lesser known artists like Margaret Hordern below.

Now it’s not an accident that I’ve chosen railway posters as a comparison. Because railway posters were popular. They were popular then, when they were sold over the counter as art as well as being displayed in stations. (There’s a good description of how this worked in Yale’s Art for All book if you’re interested).

And they’re popular now. Railway posters are probably the most collected and traded posters there are (and if you take eBay as any kind of sample, they’re certainly the most reproduced and pirated too). Lots of people like railway posters, and I suspect they like them for all the reasons I’ve railed against them before. They’re pretty, nice to hang on the wall, they look like a proper picture. And by far the most popular of all are the pictures of the countryside.

Frank Newbould, 1936

Which starts to give us some clues about the nature of mainstream British taste. It’s not the first time that this has been said, but railway posters seem to suggest that it prefers the rural to the urban, likes representation and tradition. In which case, by the by, modernism, with its paens to the city and the machine, never was going to have much of a chance, was it?

Now I know that this is an immensely contentious generalisation, and I’m rather hoping that lots of people will pile in with examples to prove me wrong.

But for the moment I still think it holds water; I might even argue that mainstream British taste hasn’t changed a whole heap since 1933 or before. It still prefers the rural to the city, it likes flowers, leaves and pictures of things it can recognise. And it still gets mostly ignored by writers and designers, architects and museums. But you can easily find it if you look. Here for example.

The inside of a National Trust shop. Does it get any more British than that?

OK, you got me to step in to the ring with this one -again. There are some pretty revealing stories in the book ‘Design and Cultural Politics in Postwar Britain’ by Jonathan Woodham about the design elite who were defining and propagating ‘Modernism’ for the masses in the 1940s and earlier. They were either emigres or friends of. They set up government bodies and exhibitions (the book is about Britain Can Make It). And from this far away, thanks to their own work and self-publicity and from our subsequent design histories, they seem pretty damn influential.

But as you say, its a small proportion of people who loved the Modernist aesthetic then. And it probably is now. I have seen some nice coverage of popular design in exhibitions at MoDA and catalogued some nice popularist stuff for them for the Exploring 20th Century London website. It tends to be left to social, rather than design, historians to bring out the detail of that stuff though. Or else it makes it in to design circles with the acceptable title of ‘kitsch’.

I think a few of the examples you cite above as ‘un-modernist’ are very much framed in modernist typography and layout, even if the illustrations are less modernist.

Not sure this helps with your continued questions however.

That sounds like a book I need to read, and will do so. Then I can cogitate more about emigrees and the cultural capital of the upper middle classes, with supporting evidence.

I am surprised that more hasn’t been done on popular taste though; it’s a long time since my MA and I was half expecting to be told that there were a wealth of new books covering just this area. The V&A was just waking up to this in my time there, and certainly Ceramics were starting to wonder if the 1950s could only be represented by a vast collection of Studio pottery and a smattering of Wedgwood alone. They also woke up to the fact that they had No Mugs At All, and this was possibly an oversight.

One interesting thing about Britain, though, is that the lower middle classes are united with the upper classes in being ignored by design history. There’s a powerful myth at work here, which I think still needs poking a bit harder.

There, even more questions. But questions are good.

Thank you for your interesting and stimulating post. I think you’re right about British taste and the countryside, but I believe that there was another factor at work with the railway companies. Their posters were aimed at getting people out of the cities and into the countryside on their trains. In the case of the Great Western Railway, at least, this led to them owning a string of hotels. The excellent Steam museum at Swindon has a good collection of photographs on display, and posters too.

Thanks for the kind words. I completely agree with you – that’s the impetus behind them.

But it does seem to me that it’s these posters (rather than the more abstract ones) that people chose to have on their walls in the 1930s, and then choose to collect today. There are so many confusing variables in what was produced, in what survives and what doesn’t, and what’s therefore collectable today, that it’s impossible to say anything for definite. So I am going out on an unprovable limb. But it’s quite an interesting limb to try out.

Er…What is meant by modernism, exactly?

A very good question. Which I need to think about before I write anything down…