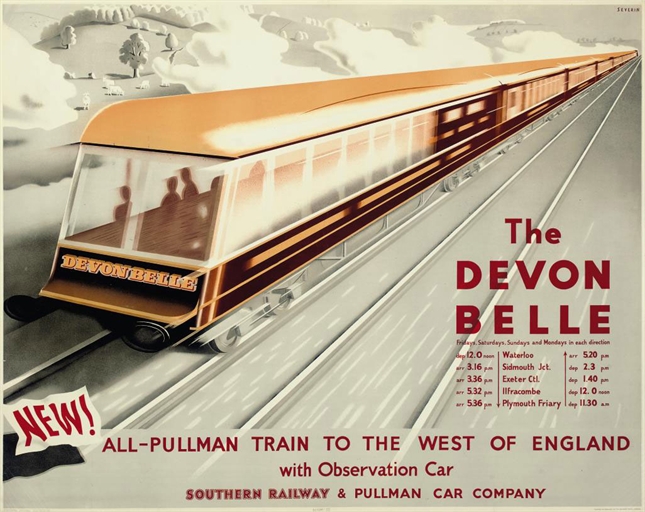

Posters on Parade

When I was trying to find some festive-looking posters the other day, my search, rather wonderfully, came up with this in the Science and Society picture library.

We find ourselves at Blackpool station in 1925, and the cart is getting ready to take part in Blackpool Carnival. Here’s what’s on display:

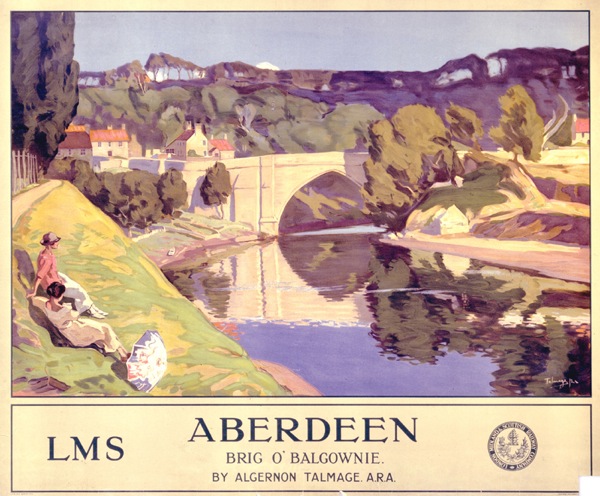

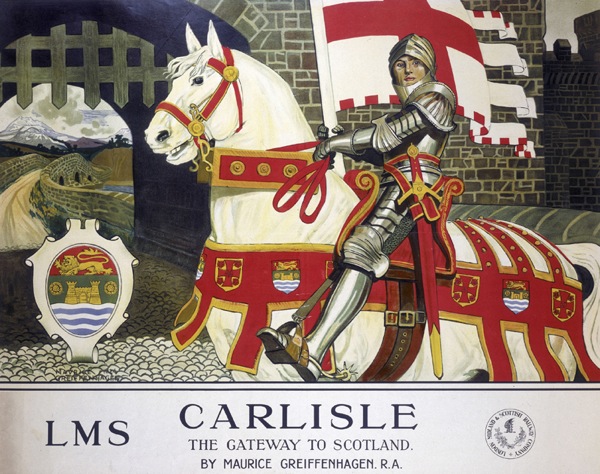

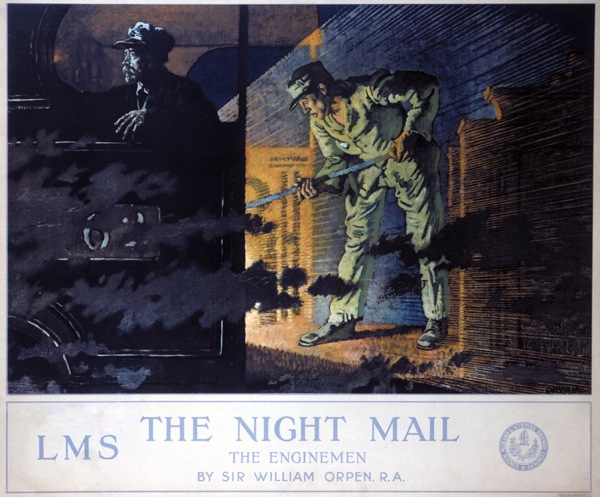

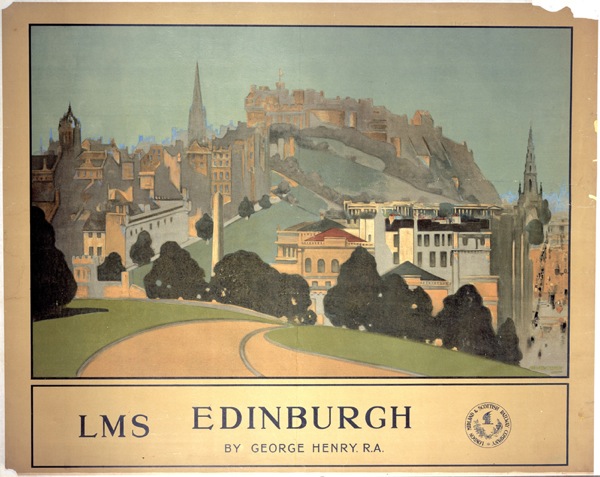

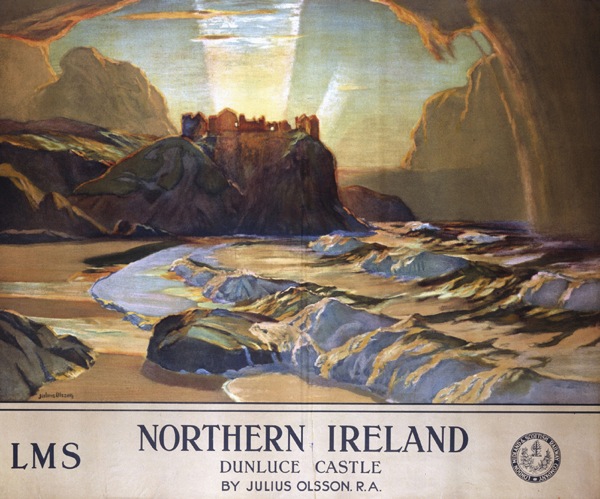

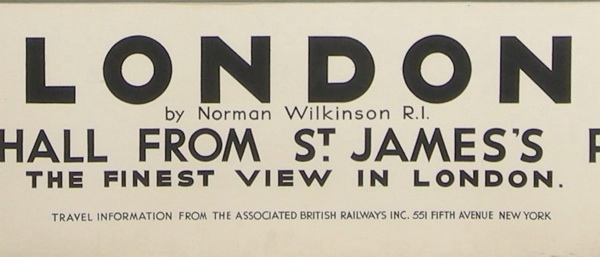

London, Midland & Scottish Railway display pulled by four horses. The display comprises railway posters designed by ‘eminent Royal Academy artists’: ‘Aberdeen’ by Algernon Mayow Talmage; ‘Carlisle’ by Maurice Greiffenhagen; ‘Edinburgh’ by George Henry; ‘The Peak District’ by Leonard Campbell Taylor; ‘The Night Mail’ by William Orpen; ‘Northern Ireland’ by Julius Olsson. The display is to be used in the Blackpool carnival.

This is clearly a fabulous thing simply for existing. But it’s also interesting in that adds a new layer to how railway posters were shown – and therefore perceived – at the time.

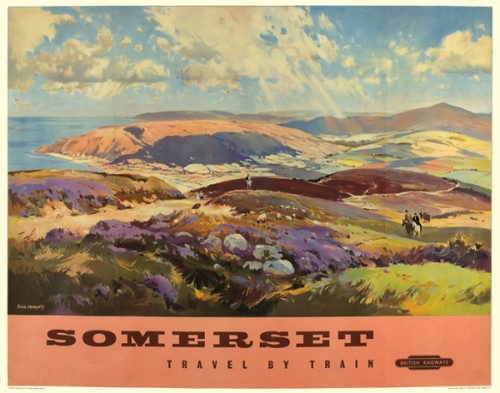

We’ve covered quite a bit of this ground on here before, mainly thanks to David Watt’s fine essay on Yorkshire railway posters, which I wrote about a while back. He makes the point that railway posters are rather unusual because they are displayed at railway stations and so the viewer can assume that they are advertising rail travel, rather than just places. So they don’t need to show trains or say ‘Travel By Rail’ and this makes them, in his words, semi-detatched from ‘mundane commercial purpose’. As a result, these posters occupied a middle ground between fine art and the grubbiness of actually selling things. (This status obviously has implications for modern day collecting of railway posters too, but that’s another thought for another day.)

These particular designs are more explicit than most about this connection with fine art. All of the posters on the wagon come from a set of sixteen commissioned by the LMS from Royal Academy artists; they are indeed fine art being displayed on a poster.

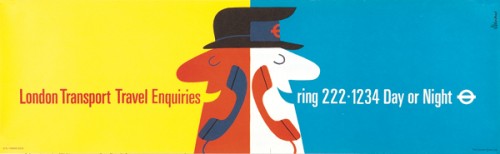

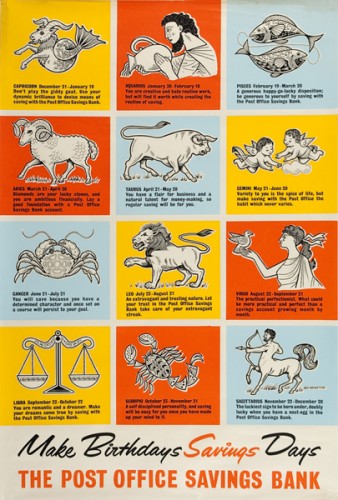

As such, they link up with another idea that has come up before, the sense of public bodies using artists and painters in particular for their posters as a form of social good. I’ve discussed this before in the context of the GPO, Shell and London Transport posters.

The involvement of Shell shows that it wasn’t an attitude that was confined to state-own entities alone, and a similar ethos of public service seems to have been present in the railway companies before the war. This wasn’t just confined to their publicity; the LNER kept open lines that were running at a loss because they felt that people needed access to them. So these posters clearly fall into an established tradition of posters which are on the borderline between fine art and advertising, and which are produced, in part, because they are felt to be part of the railway companies’ duties to the wider society they serve.

What’s so interesting about the carnival cart above, though, is that is shows that the LMS had a slightly different attitude to the audience for these posters than I would have imagined – and it’s one that I find rather endearing.

Until now I’ve always thought of these these posters being on display in stations, where passengers could inspect or ignore them at their will, or in occasional exhibitions (more on these here if you’re interested), where I would have imagined the audience was predominantly middle class.

But at Blackpool, the LMS is taking these posters out, which in itself shows a degree of pride that I wouldn’t have expected, but what’s more it’s taking them out in front of an audience which is probably not quite so genteel and alongside dancing girls, giant dogs and, er, people dressed up as food.

So the LMS is positioning the posters not as ‘high culture’ being foisted on the working classes from above, but very much as part of a thriving and quite varied popular culture.

There are a few other hints too, that this point of view might have prevailed. This series of posters was one of the LMS’s best-sellers, with Carlisle a particular favourite. But when I was looking to find the particular posters on display on the cart, I also found a reference to a colour print of William Orpen’s Night Mail. There are no dimensions given, but I imagine that this would have been a much more affordable version than buying a copy of the original poster. (And who did buy those? I would love to know.)

Perhaps we need to rethink what the fine art elements of railway posters meant at this time, and indeed later on when they were used by other companies in the same way. We see something that was imposed on an ultimately indifferent population who were not interested in art, and this may indeed be how the original commissioners of the posters too. But it’s possible that these images were enjoyed and taken up by a much wider variety of people than we, slightly snobbishly, tend to imagine.