Now I began this post, if I’m honest, intending simply to poke a bit of fun at poster dealers, and in particular the prices they charge.

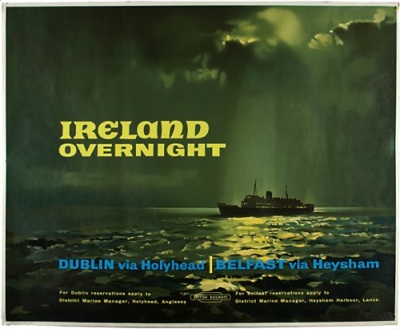

Because now and again something comes my way which makes this almost irresistible. Like this.

Or to be more precise, this.

Now in my head, nothing, but nothing could make this 1960s railway poster worth £900, even if it is by Claude Buckle. Not the Piccadilly premises of these lovely dealers, nor their need to pay the legions of Sloane Rangers who stroke it daily, nor any other excuse they offer could ever justify that price to me.

And why am I so sure? Because we paid £80 for a lovely bright copy, with another poster thrown in to boot, last year. Although I’m not entirely sure why we did as it’s a bit drab to have around the place and I can’t imagine it will ever end up framed. Only a few edge tears distinguish it from its Mayfair relative. Should you feel like doing the same, it’s pretty easy to pick one up at the railwayana auctions for between £100-£250, and they appear with reasonable regularity.

So far, so quite funny. Although the more I consider it, the more I think the joke is less on the poster dealers than on their clients, who will, after all, have paid several hundred pounds more than they they needed to for this poster.

But then I did a bit more digging, and found the same poster had sold at Christies for £588 and then £657 there (in 2002 and 2004, since you ask). Which makes the Sotherans price look more reasonable, as well as forcing me to reconsider how hard I am laughing – and do some proper thinking to boot.

So, why are people paying £900 for a poster when they could get it for £600, or £250, or even £80? To some degree, they do this because that’s the way the antiques trade (or any branch of it like poster dealing) works. Things, whether they are Claude Buckle posters or undiscovered Rembrandts, are sold at provincial auctions where no one knows what they are and so they go for a little bit. They then work their way up the food chain via specialist auctions or middlemen, costing a bit more each time, until they finally end up in a Mayfair showroom for many, many times what they originally cost. And everyone is happy.

This works because (I’m dredging up my memories of A Level Economics here, forgive me if this makes no sense) the market is imperfect. To be precise, the market information is imperfect – the regional auction doesn’t know it’s a Rembrandt (or a nice poster), the man with bottomless pockets in Central London doesn’t know that he could get it much cheaper somewhere else. And these imperfections are what drives a whole chain of price rises and exchanges.

Except there is one problem with this model now, and that’s the internet. Should you choose to look for it, all the information you ever wanted to know about posters and their prices is out there on the web. And the proof of that is this blog post.

I’m not a poster dealer with twenty years experience, gained in hanging around every provincial and Christies auction, I don’t even live in London. And when I started writing this post, all I knew about that Buckle poster was that a) we had bought one for £80 and b) that there was a dealer in Mayfair pushing the boundaries of plausible pricing. Now, just an hour later, I’ve got its whole auction history at my fingertips, and I’ve also had a crash revision course in the theory of perfect markets.

In theory then, the old model shouldn’t work any more. Thanks to the internet, everyone with more than ten minutes to spare will know that they can get that Claude Buckle poster for £80-£200, they can see which auctions it’s coming up at – and they can even buy it without having to step away from their computers. So they don’t ever need to pay more than the market price. It’s nearly perfect, if you’re an economist that is. Rather less so if you want to make money dealing in posters.

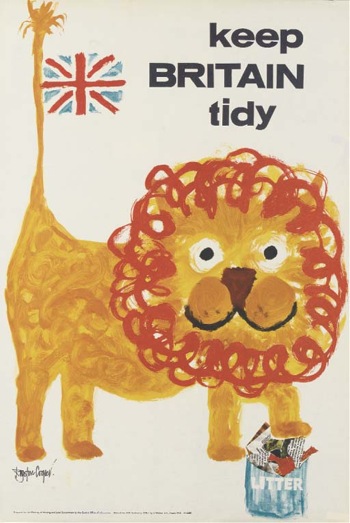

In Piccadilly, people with bottomless pockets probably will still walk into a gallery and buy something for what a dealer says its worth. But elsewhere, I think this is more than just a theoretical model, it is already starting to make a difference. In my previous post about Christies, I’ve already noted the drop in auction prices for post-war posters. Here’s another example, Royston Cooper.

This went for £660 at Christies in 2005, just £200 three years later. There may be other factors involved – the collapse of the world economy, that kind of thing – but I’d still be prepared to bet that the internet and all its information paid a part in that. After all, why would you pay £660 for a poster when you could pick it up for £60 on eBay?

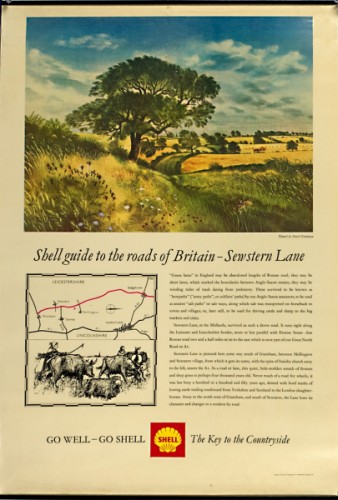

Having said all of that, the imperfect world did have its upsides. Sotherans also have this on offer.

It’s a Shell educational poster by David Gentleman, and they’d like you to pay £198 for it. Now Mr Crownfolio and I went through a phase of rather liking these Shell posters, which means that I’d really like them to be worth the sharp end of £200 each. Because that would mean that there is £7,000 sitting quietly under the spare bed. Sadly, I don’t think it’s really true.