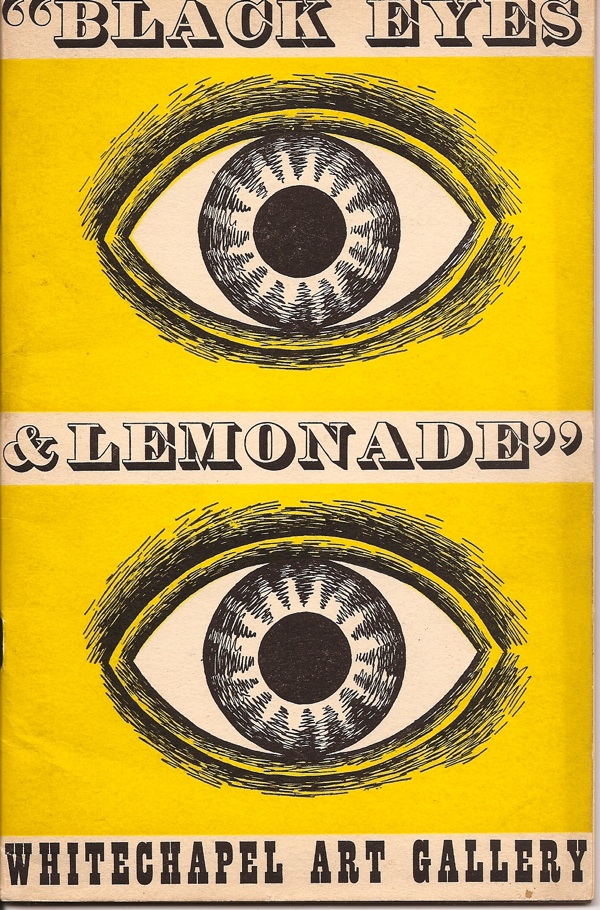

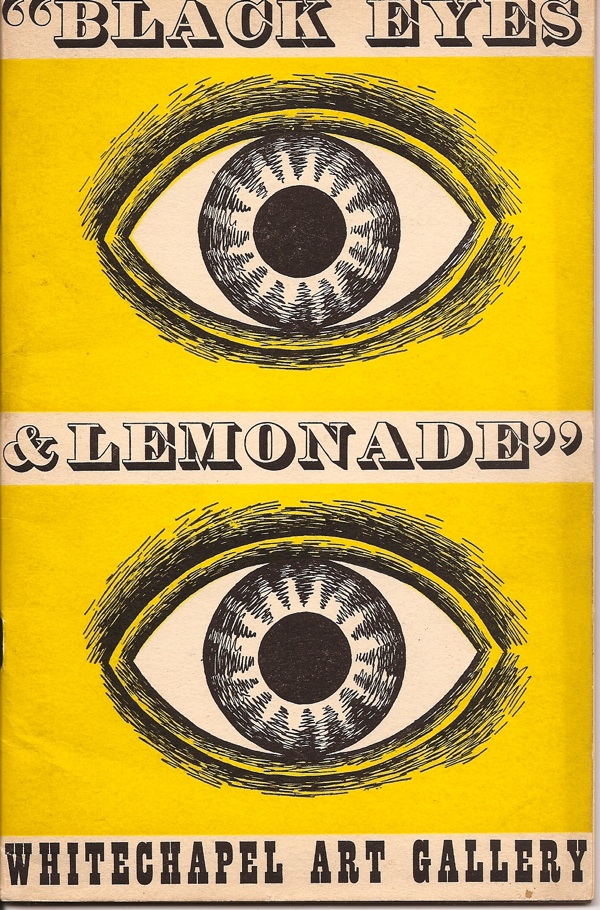

We’ve been beaten to it! For a while now, me and Serge and Tweed have been thinking that what the world needs is a complete re-staging of Barbara Jones‘ Black Eyes and Lemonade Exhibition, which was held at the Whitechapel Gallery as part of the Festival of Britain celebrations in 1951.

I’ve written about the exhibition before on here, as well as posting some details of the catalogue (from which we learn that a good third of the exhibition at least came from Barbara Jones herself).

But it’s still worth reprising what I’ve said before, which is that Black Eyes and Lemonade was a very important exhibition whose importance – seen from the perspective of today – rivals the spindly-legged modernism on display at the South Bank itself.

I say this for two reasons really. One is that the displays at the Festival of Britain itself were brilliant but at the same time also quite obvious. The modern world of technology and leisure was the big promise that had been made at the end of the war; this dream was one of the things that people had been fighting for. So while the displays of modern architecture and labour saving devices at the Festival were amazing and exciting, all brought together for the first time, one thing they were not was unexpected. But Black Eyes and Lemonade was.

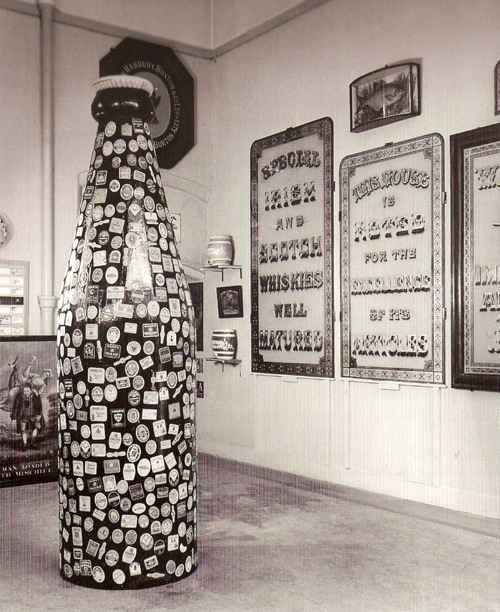

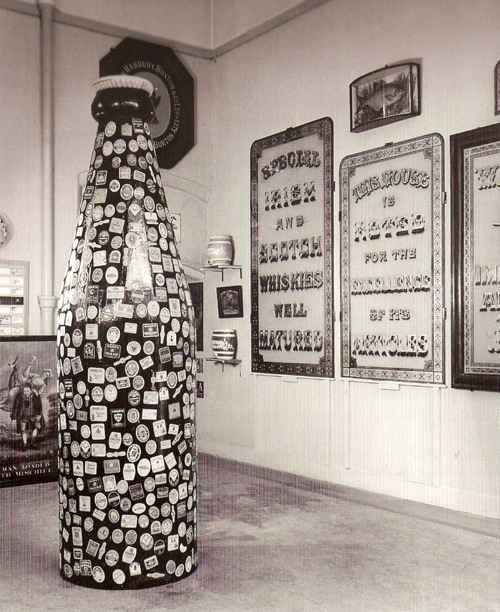

It takes a particular kind of contrary genius to look the other way when everyone else is pointing towards a radiant future, but that’s exactly what Barbara Jones did. She collected up pub lettering, popular advertising and naive art – in short, all the things that she felt were not only neglected now but were also in danger of disappearing under a wave of television, good modern design and indifference. (As one of the main artists on the Recording Britain project, Barbara Jones had form in thinking about what might be neglected and in danger of disappearing).

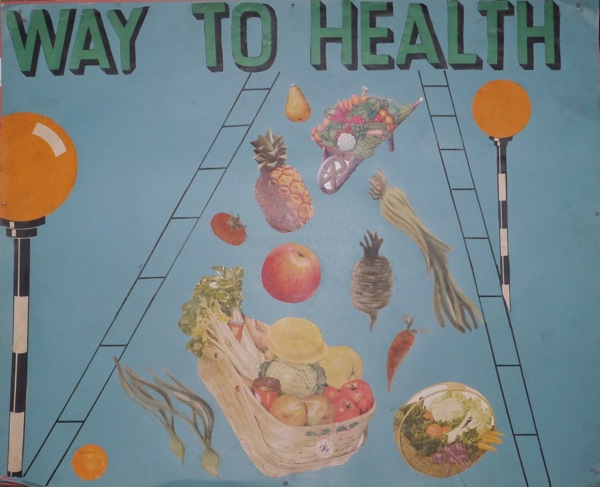

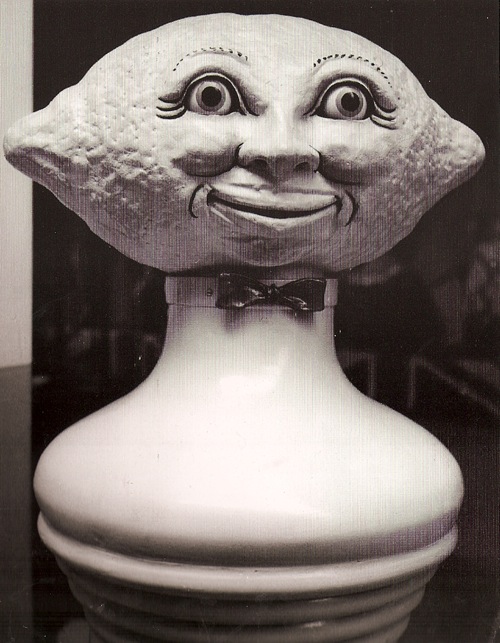

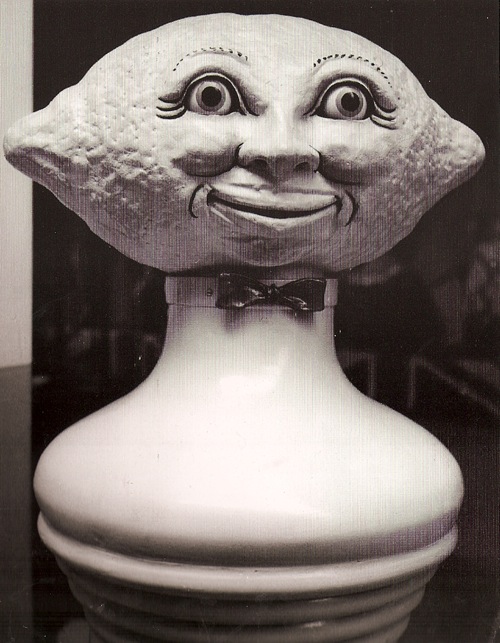

But Black Eyes and Lemonade was also revolutionary in that it was the first time popular industrial art had been allowed into the hallowed halls of a gallery or museum. People at the time were genuinely outraged that the Idris Talking Lemon was being displayed as though it were a piece of art.

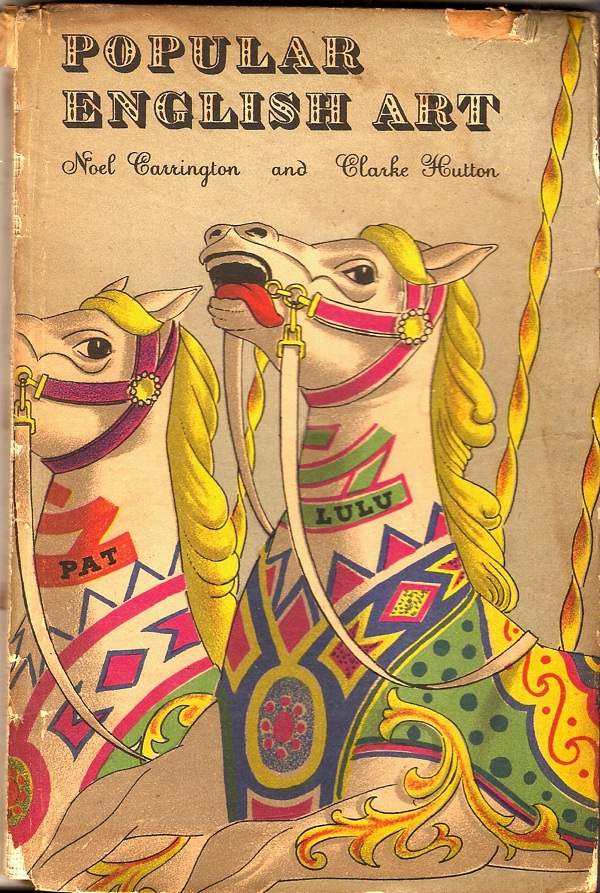

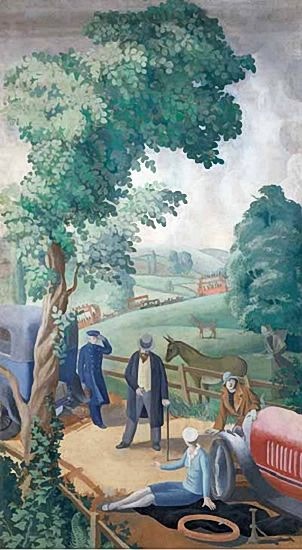

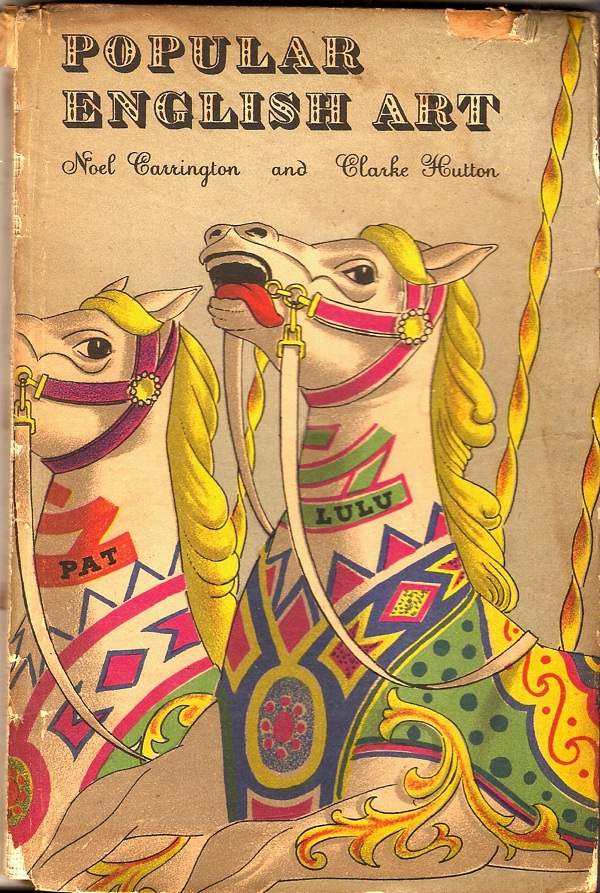

Of course poular art had been celebrated before. Here’s just one example, Noel Carrington’s King Penguin on English Popular Art, from 1945.

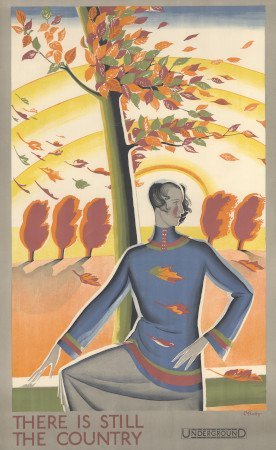

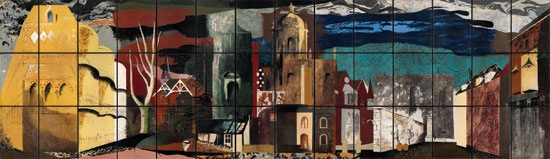

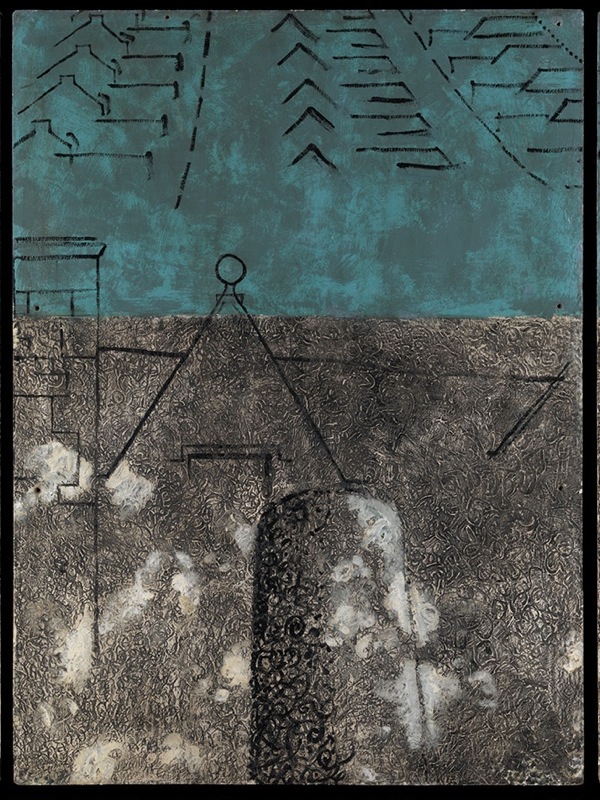

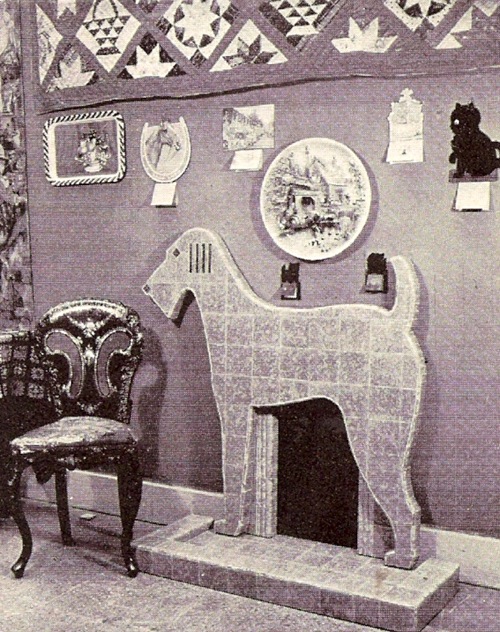

But you won’t find any talking lemons in here; instead it’s all horse brasses, smocks and twelfth century hinges from cathedral doors. The closest it gets to modernity is the sign painting on barges and an appreciation, shared with Black Eyes, of Victorian pub interiors. It certainly wouldn’t have featured anything like this.

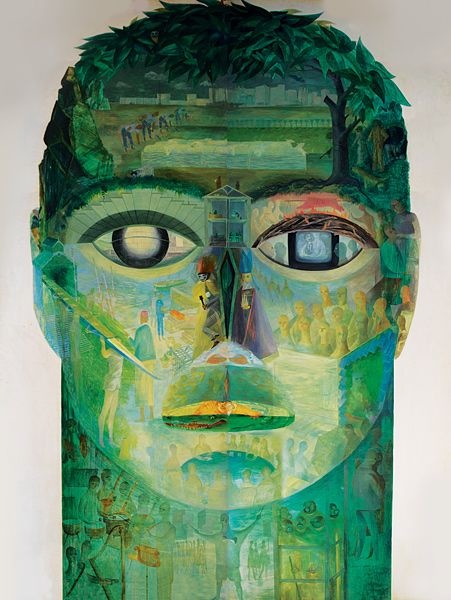

Black Eyes and Lemonade was the first time that the popular products of the industrial age had been celebrated in this way. It began a process which leads, in the end, to Grayson Perry and Jeremy Dellar, which makes it in my book a very good thing.

The good news is that these kind of opinions are no longer a minority view, which is why the Whitechapel Gallery, along with the Museum of British Folklore, are now revisiting Black Eyes and Lemonade for an exhibiton which has just opened. Now it’s an ‘archive exhibition’, whatever that means, and I can’t tell you any more than that as I haven’t been to see it yet. Although it is on until 1 September, so there is some time.

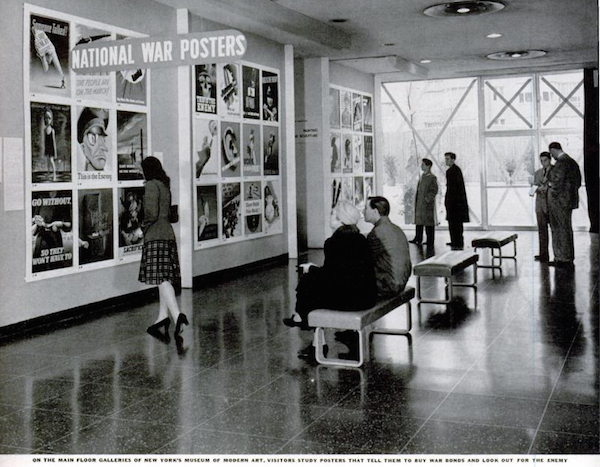

But I will, not least because the Whitechapel have sent over, by way of tantalising preview, these photographs of the exhibition in situ.

Look at that National Union of Railwaymen banner hanging from the ceiling, it’s a real index of how far we have all absorbed Barbara Jones’ ideas about what is worth celebrating in popular art.

It doesn’t only link us to Jeremy Dellar and his modern banners produced for the Manchester Festival a few years ago, the idea has now become even more mainstream than that. For Michael Wood’s most recent series about the history of Britain, a recurring motif was the banner, commissioned for the programme, which depicted the different stages of history featured in the series.

Here it is again from a different angle, along with a quite splendid selection of other stuff.

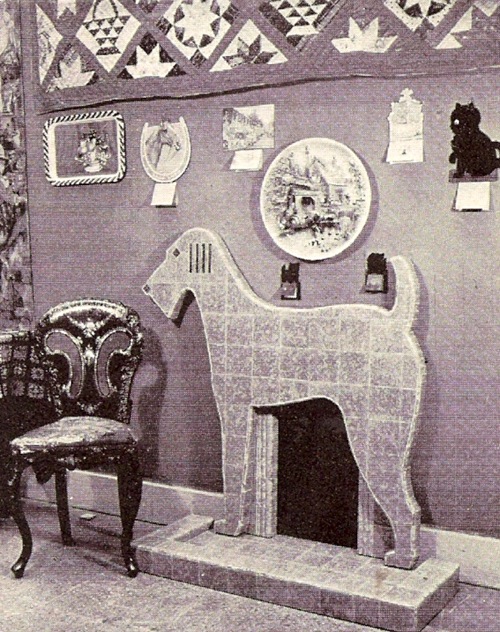

From the pictures they sent me I also learned that the Airedale fireplaec has not only survived, but is now preserved in the Design Museum collections.

There is a whole story in that, just waiting to be told, but whatever it might be I think Barbara Jones would be rather pleased about the result.

Anyway, I will obviously be going as soon as I can possibly manage, if any of you get there before me, please do report back.