The recent announcement from the British Postal Museum and Archive announcing that they have upgraded their online catalogue may not have been the most retweeted 140 characters in the history of Twitter. But the news is actually quite exciting.

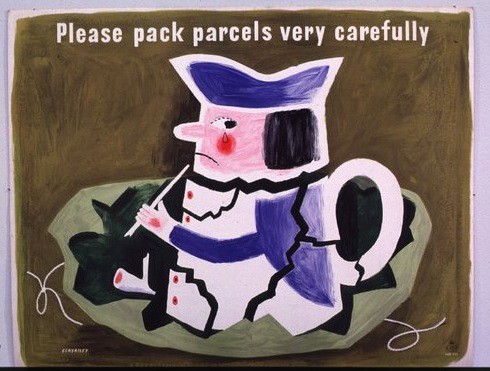

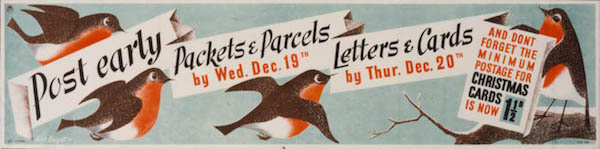

On an entirely practical level the images are now larger than a postage stamp. The particular joy of this is that I can now get a proper look at the van posters, which are some of my favourite things in the world.

I wonder if any of these have survived outside of the BPMA’s collections? I’ve never come across one out in the wild.

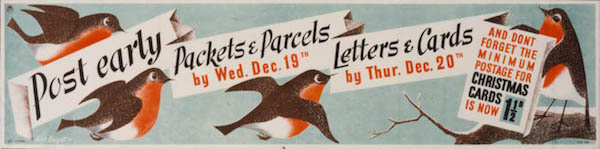

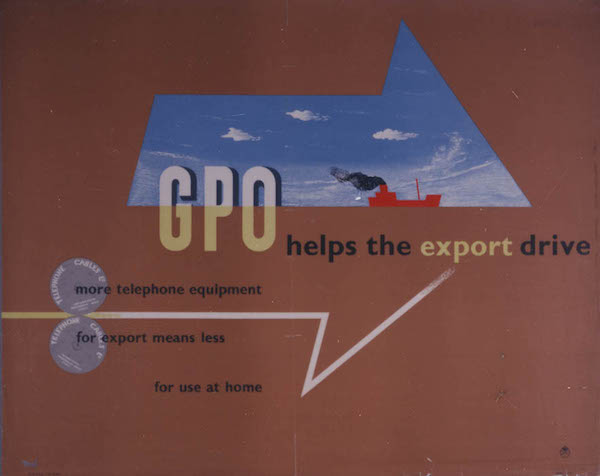

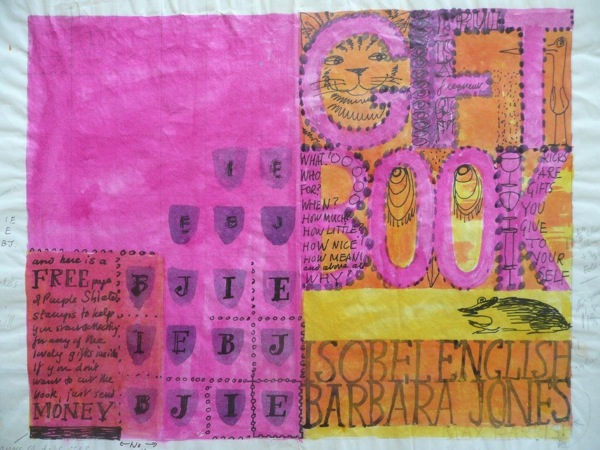

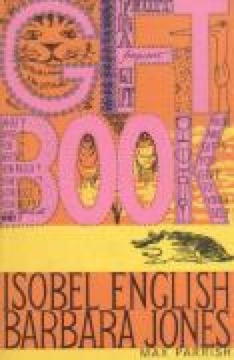

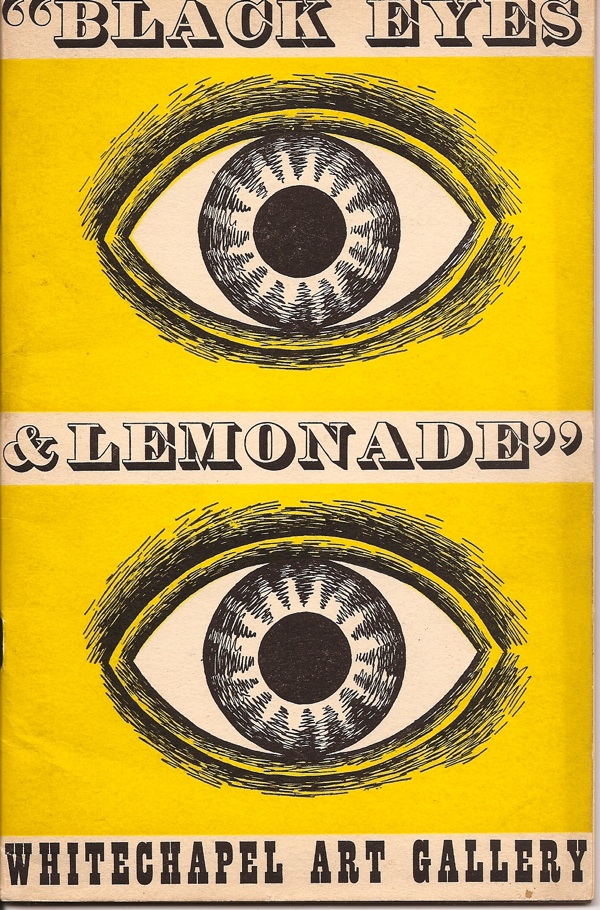

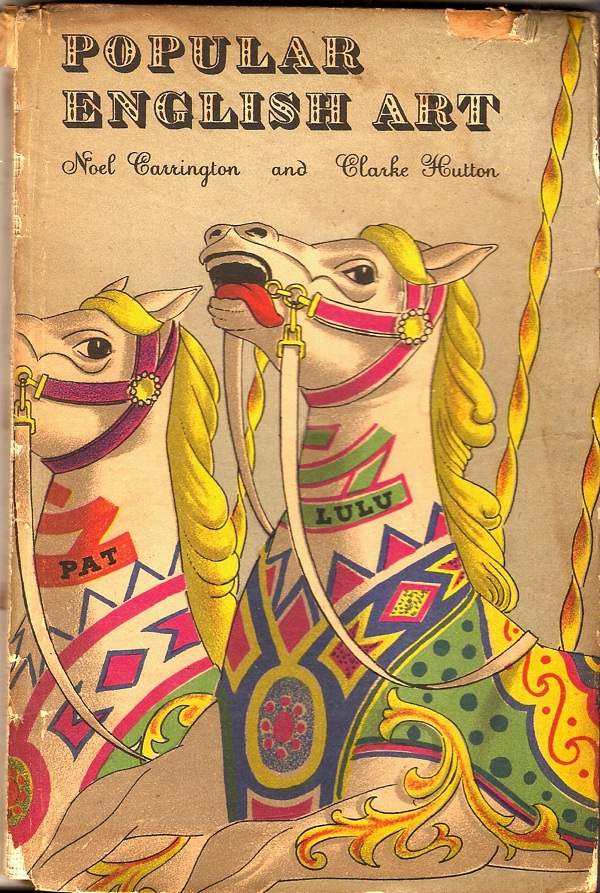

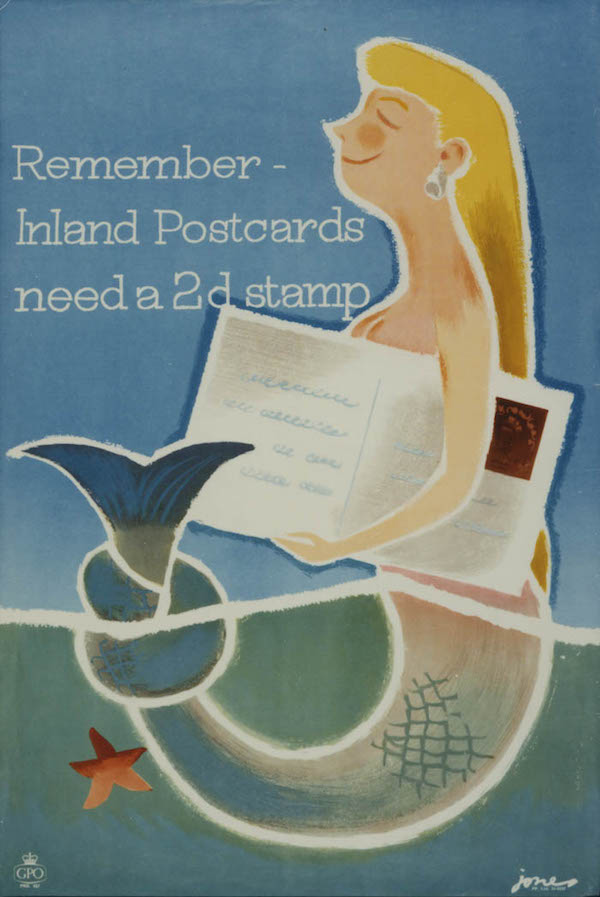

More than that, a whole lot of new material also seems to have been catalogued for the first time. I had no idea that Barbara Jones had ever designed a poster for the GPO, but the evidence is there in full colour.

It’s from 1956, since you ask.

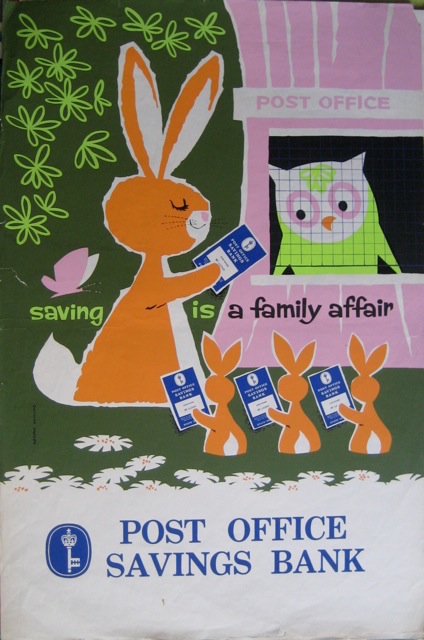

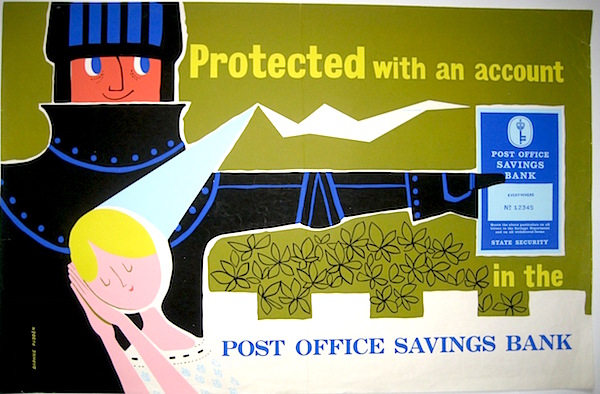

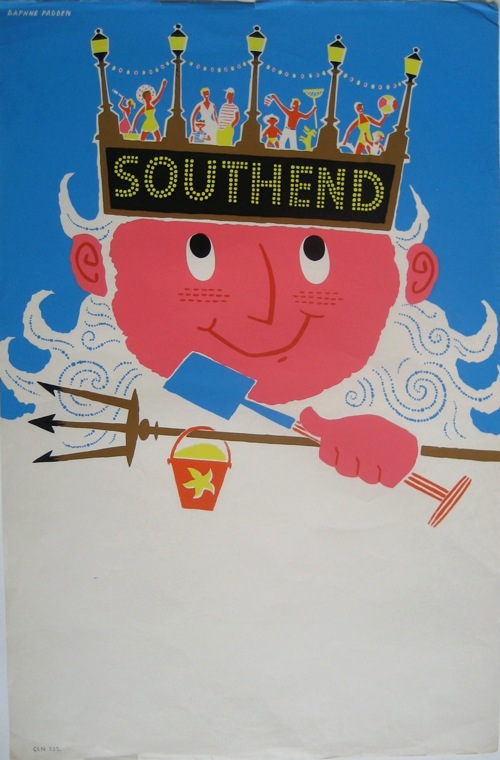

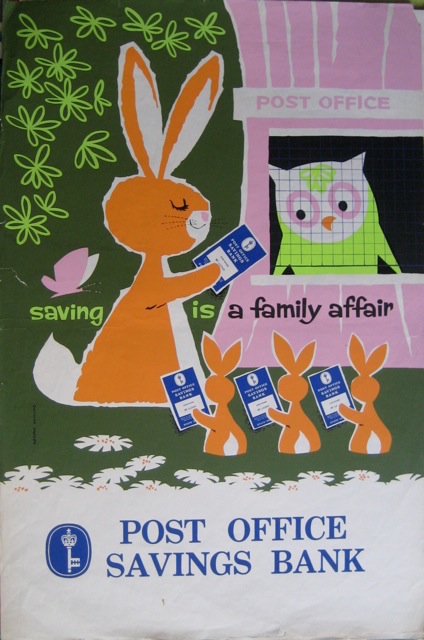

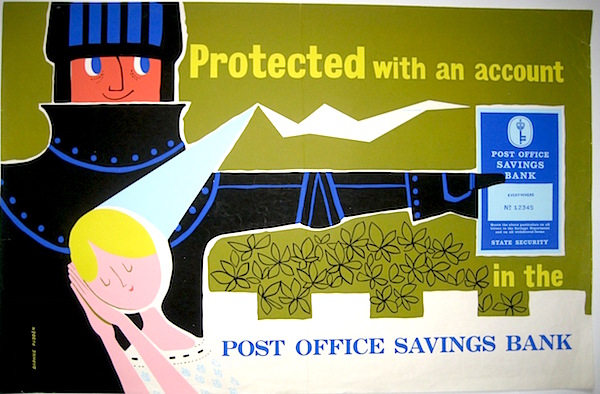

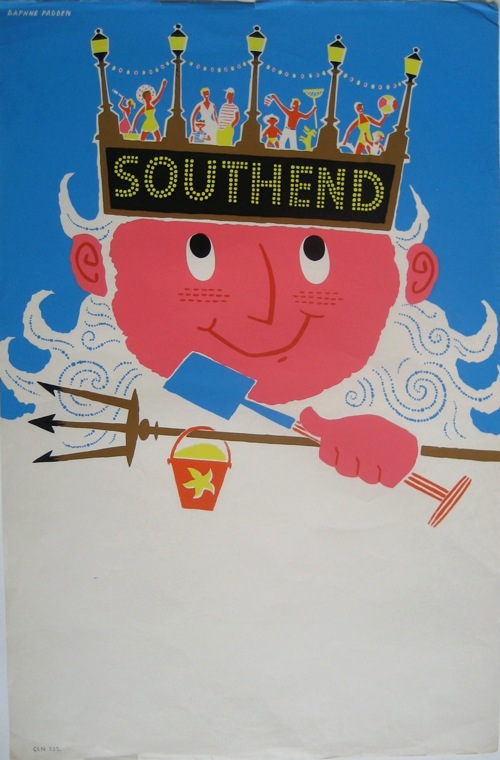

In addition, for the first time the catalogue now includes some Post Office Savings Bank posters. This is clearly still a work in progress as, currently, there’s nothing in there by Daphne Padden and she did some of her best work for the POSB.

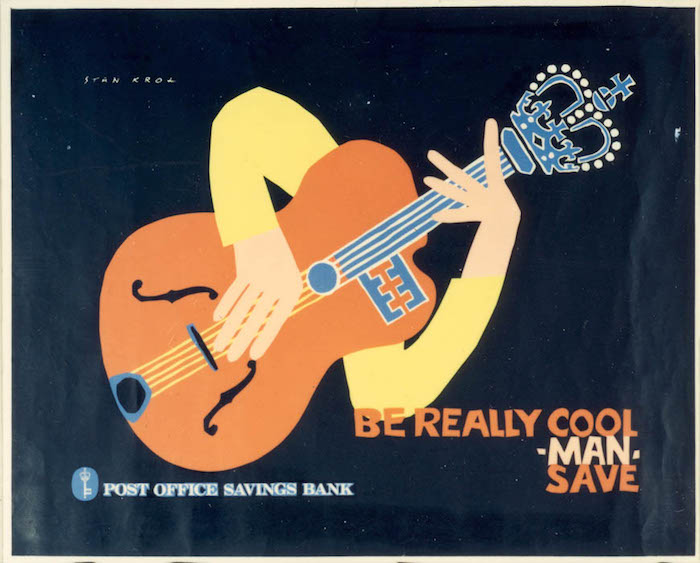

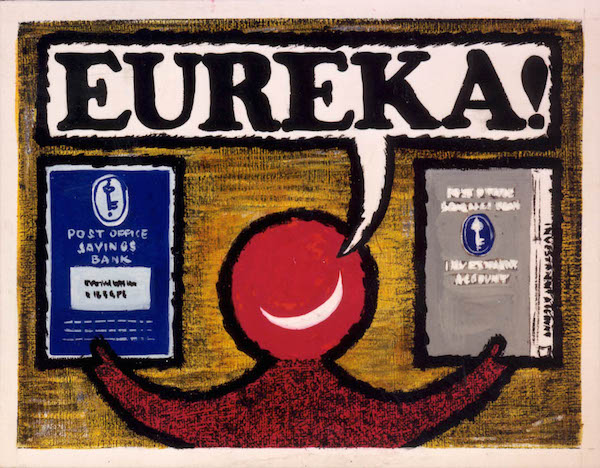

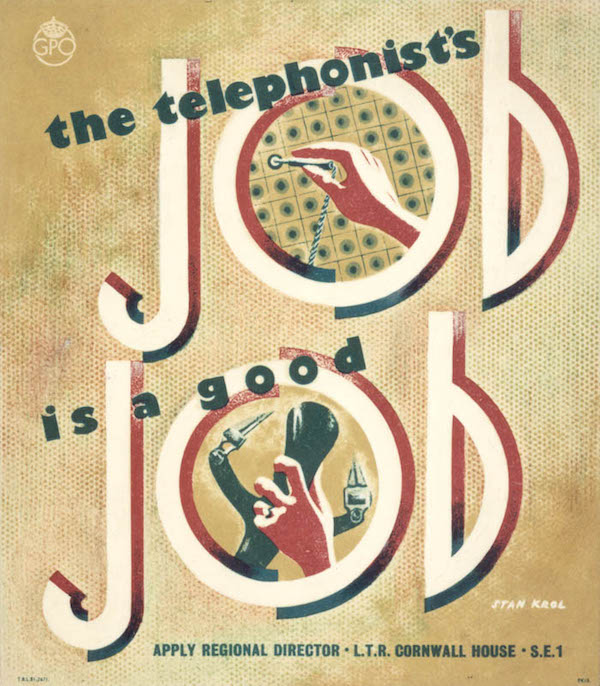

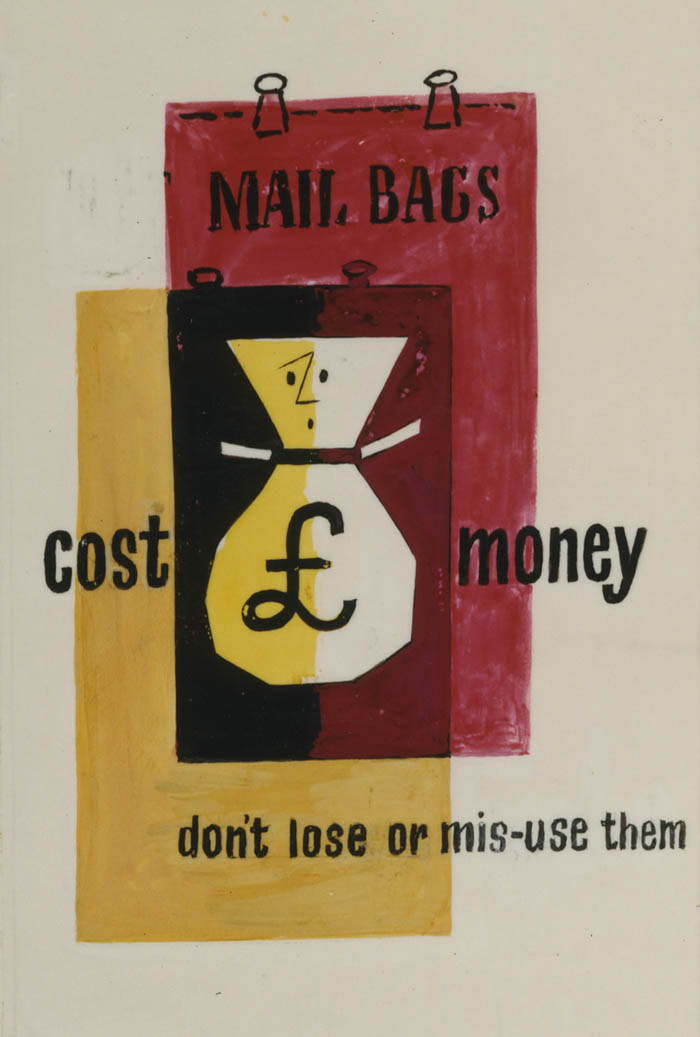

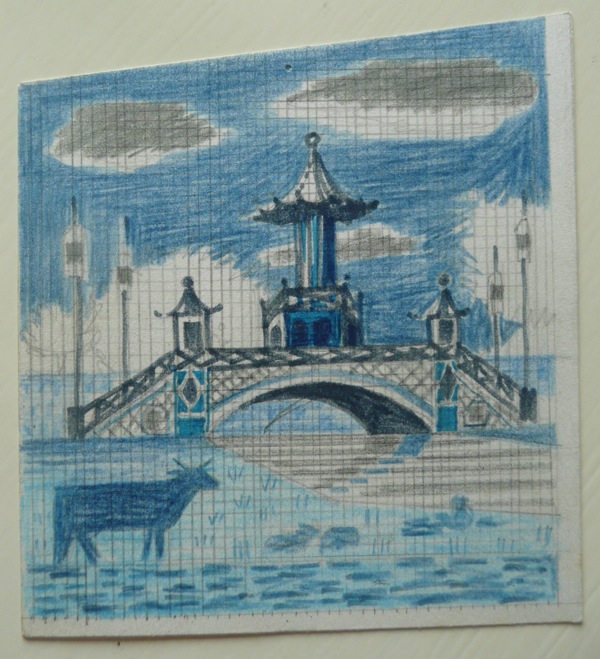

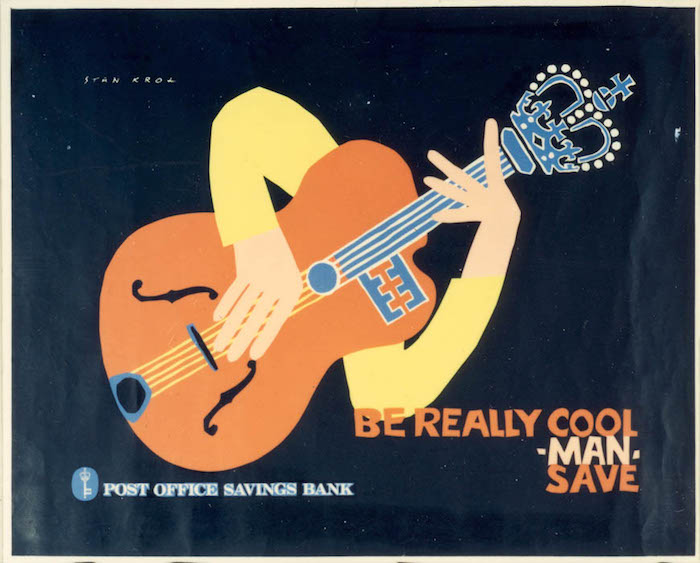

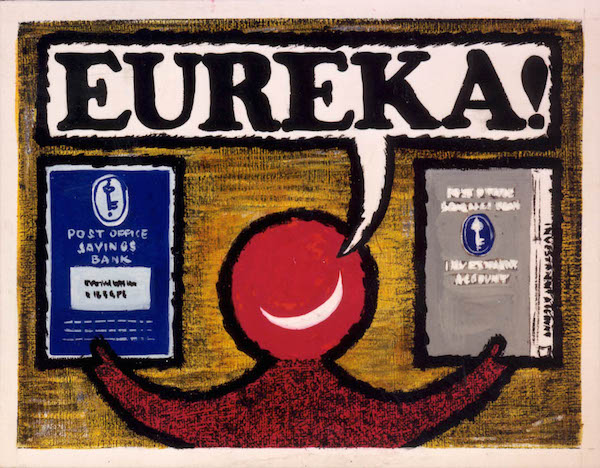

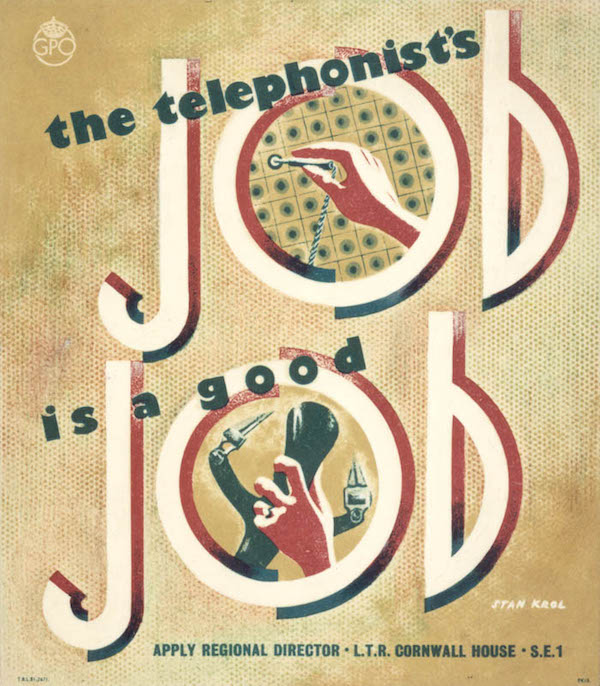

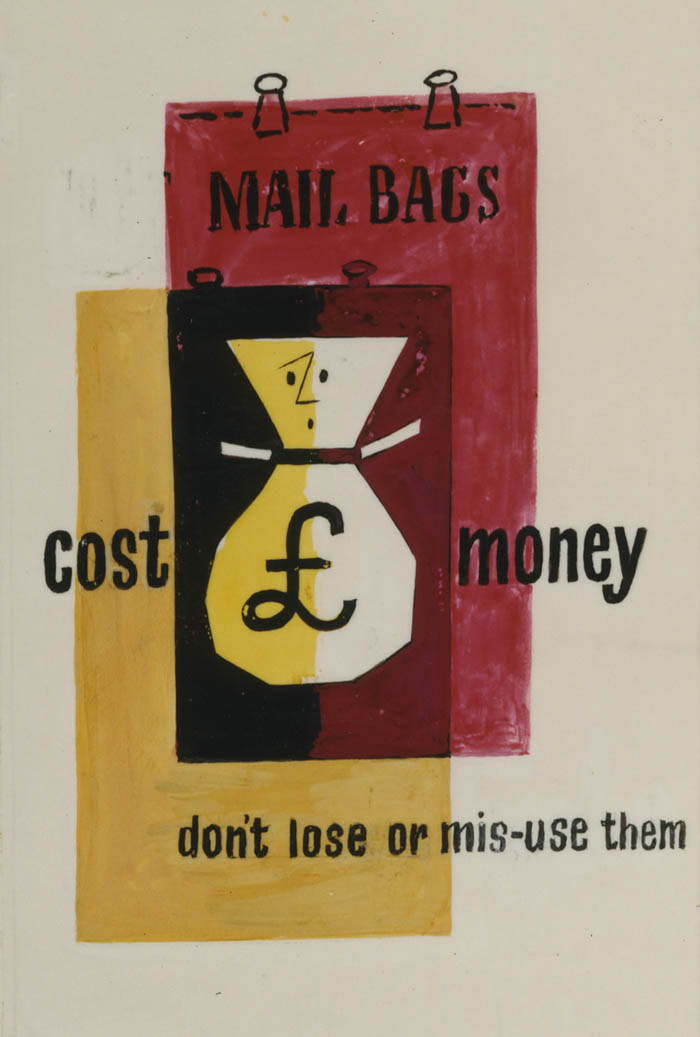

What is in there, though, when you search for POSB posters, is a lot of work by Stan Krol, quite a bit of which I’ve never seen before.

With both posters and artwork included.

All of which is a salutary reminder. It’s not just that archives themselves are important, but also the way they are arranged and made accessible. Because both of these things can change the way we think about the past.

Let’s just start with the contents. A couple of years ago, I wrote about Stan Krol, saying that I couldn’t find out that much about the man or his output. Obviously, pages of Stan Krol posters in the BPMA catalogue rather changes things.

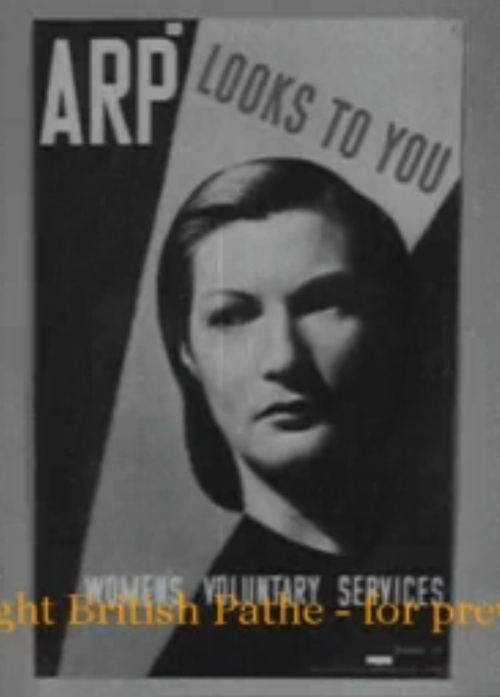

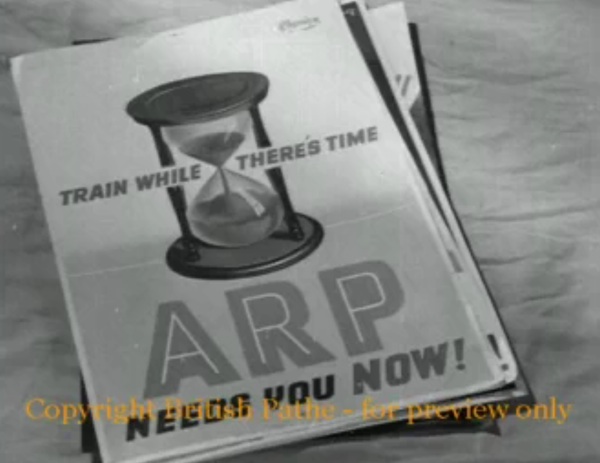

Morever, in the new, exciting BPMA catalogue, the results also come up differently. Back in the day, the archive used to sort the results, so that the artwork would come up first, then the posters. So I would skip through the artwork, and just look at the posters instead.

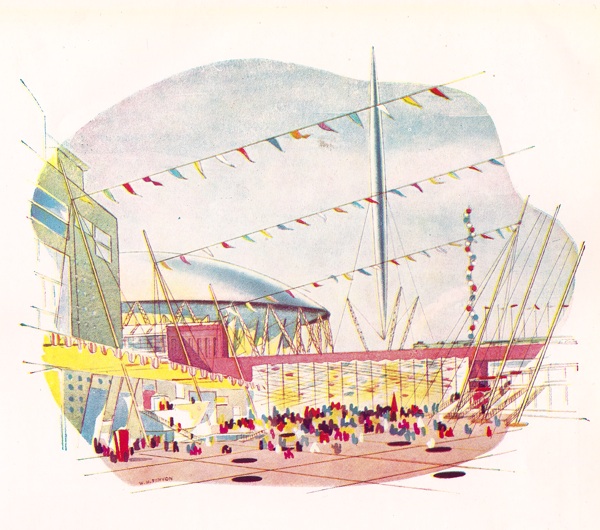

But now the two come up intermingled, which means that I don’t miss items like this Tom Eckersley internal poster, which shows as artwork but not as finished poster.

All of which will, I am sure, make other differences to the way I think as well, even if I I don’t entirely know what the results will be yet. Watch this space.

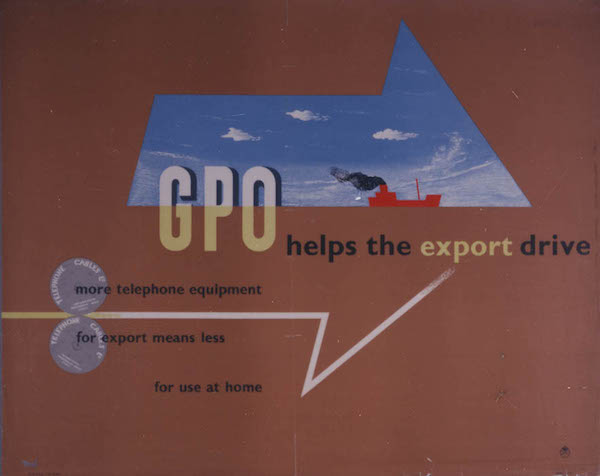

The biggest change of all, of course, is just the fact that online archives exist in the first place. This blog, and I’m sure much else besides, simply wouldn’t exist without them.

If I had to travel from London to York and all points in between simply to see posters, it’s just not going to happen without a private income or a job that is prepared to pay for me to do it. Neither of which things exist. So online archives enable me, and many many other people, to think more widely and to see more points of reference. But there is another more subtle benefit too, which is that they also allow people like me to choose.

Prior to this, the only way I would have been able to see any GPO posters would have been either in auction catalogues, or in books. In each case, the posters would have been pre-selected. But give me an archive and a computer, and I am at liberty to decide which items I find interesting. So, perhaps, I am less likely to fall in with the accepted canon of ‘good’ posters as a result, and history ends up being written slightly differently. Which is clearly a good thing.

So hurrah for the lovely new BPMA catalogue and archives in general.

But wonderful as all of this is, we mustn’t let this blind us to the fact that not everything is archived. This may sound like a truism but it’s actually a really important point, and it’s something I think about a lot in connection with Daphne Padden.

Her work has been massively under-recognised over the years, and her profile still isn’t as high as it should be. Now there were plenty of reasons for this – and being a woman working on the outskirts of London must have played a considerable part. But a big part of it has to be because she just worked for the wrong people.

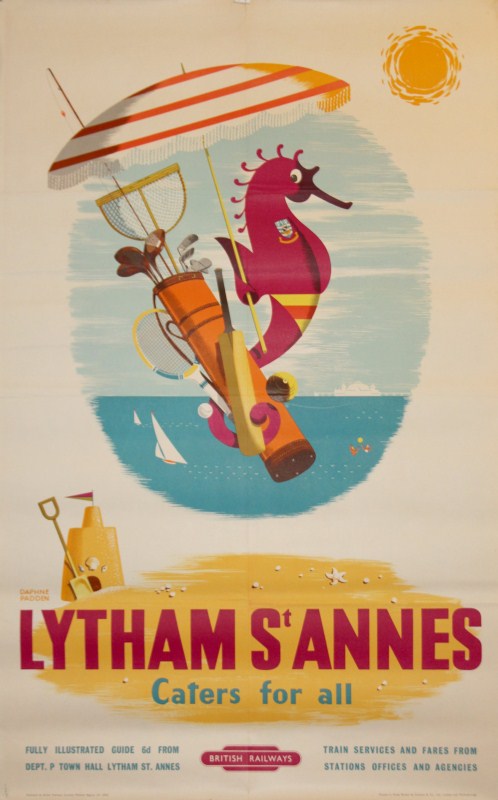

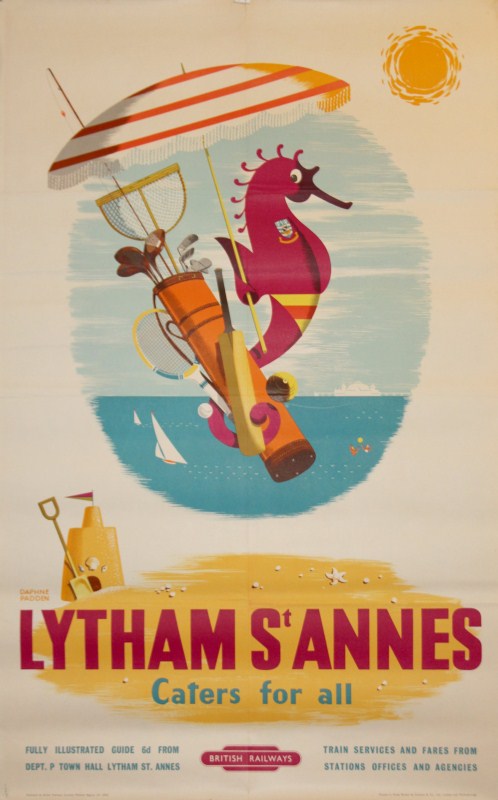

Railway posters were sold and collected when they were produced, and nowadays they are traded at auction, reproduced in books and as fridge magnets, and kept in a socking great archive in York (now there’s an interface that could still do with taking a long hard look at itself). But she only ever did a few of those.

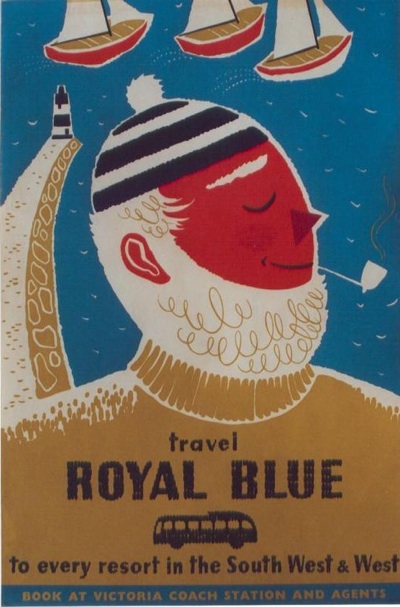

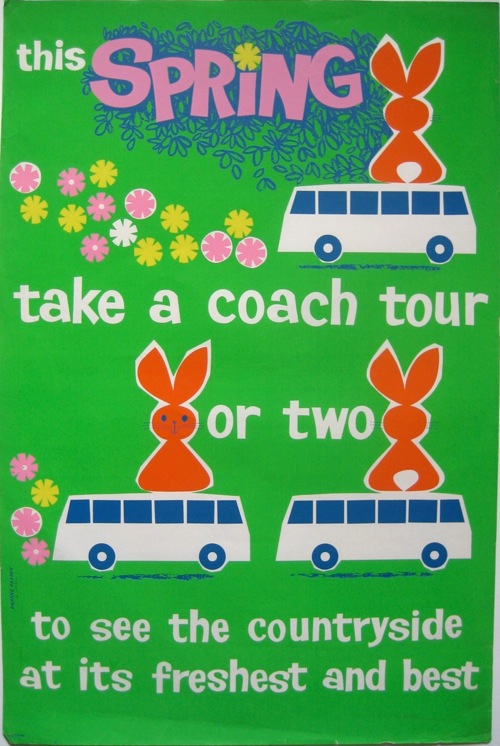

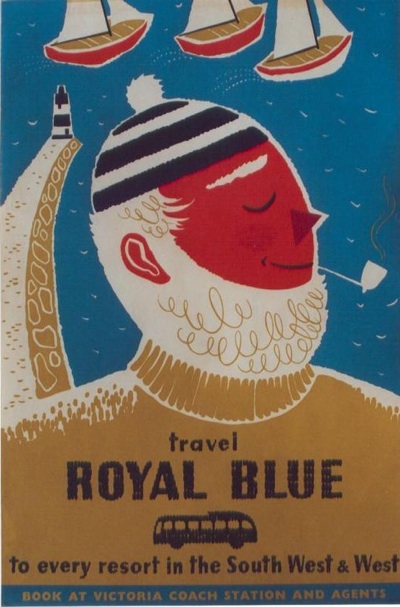

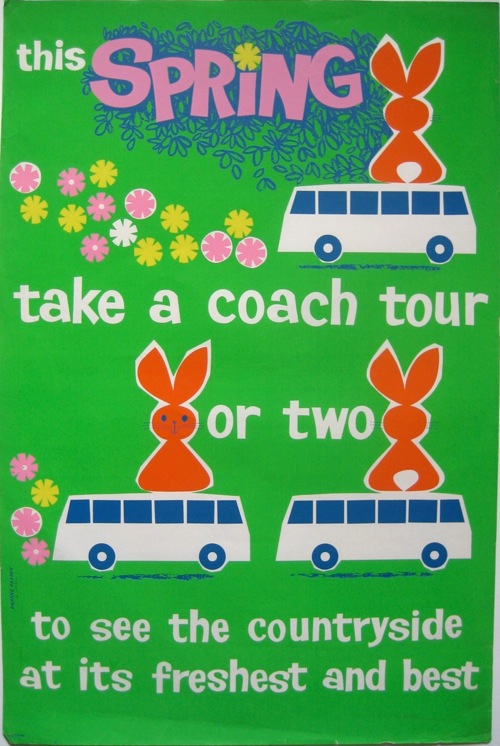

Instead her main customer were the coach companies. And where is the coach archive, I hear you ask? Well exactly.

There isn’t a collection of these anywhere; hardly any survive and it’s possible that the most comprehensive selection (now that the Malcolm Guest collection got sold) is in our spare room. Which is ridiculous.

And because my spare room doesn’t have an archivist or – more to the point – doesn’t actually contain more than a couple of dozen coach posters when hundreds were produced, people don’t know about these designs. So they don’t get reproduced in books, or as fridge magnets, and in the end they disappear from view.

Along with the designers, like Daphne Padden, who produced them.

So while we can have a lot of fun with the archives that are there, it’s always worth using them with half a mind to the ones that don’t exist.