Double Pott and an Elephant, please

It’s been a while. Sorry, I’ve been busy writing about hill forts and cows and men who stride out to walk.

But all the time, this thought has been nagging away at me. It’s a very simple question, which someone asked me a while back, and I was astonished that I had never thought to ask myself.

How did the poster sizes get their names?

Because let’s face it, poster sizes are not merely daft, they are irrational. As Tom Eckersley will now demonstrate.

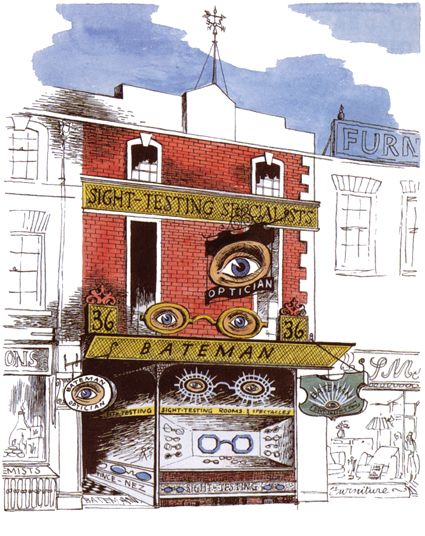

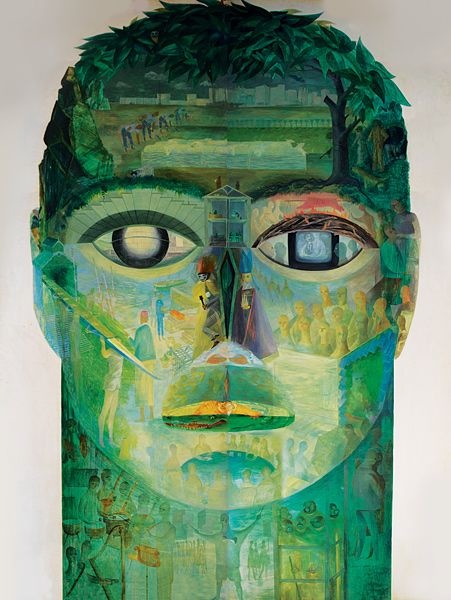

The most general proportions of poster sites in Britain are illustrated here:

Extreme lower left: Crown (15 x 20 inches)

Lower left: Double Crown (30 x 20 inches)

Top left: Quad Crown (30 x 40 inches)

Right: Double Royal (40 x 25 inches)

Tom Eckersley, Poster Design, 1954

The left hand Crown sizes are predominantly used for commercial posters.

While the right hand Double Royal size is mostly used by the train companies and London Transport.

And of course if you make a Double Royal but twice the size, that would be a Quad Royal, which is me, and also used by the railway companies for their larger posters.

But how did they get these names? I pondered this for a while, and then I had a thought. Perhaps the Royal isn’t just a poster size, but began in the first place as a name for a certain size piece of paper.

And so it turns out to be. There’s a lovely chart on the website of the British Association of Paper Historians which gives the dimensions of all sorts of Old English Paper Sizes. These include, of course, Royal and Double Crown, and so the paper gave the posters their names. Although the chart does also make me realise that there were many missed opportunities. Why did no one choose Double Pott as a poster size, or Postal, or Elephant?

For six months or so I was quite happy with that explanation, until I started writing this blog post, at which point I started to wonder whether I could trace things back further. Pleasingly, I can: all the way back to 1389.

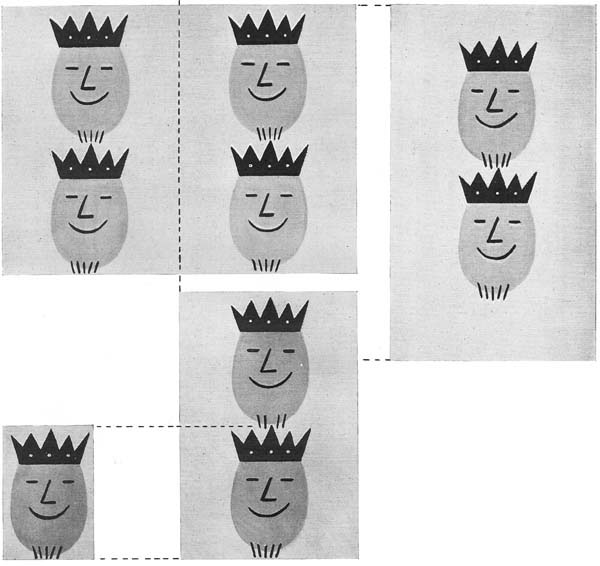

Meet the Bologna Stone.

The original (what’s pictured above is a seventeenth century copy) stood in the centre of the city of Bologna in Italy and laid down the law about paper. There were to be only four sizes of paper in the city, and these were they. If anyone produced paper in any other shape or format, it would be destroyed. And take a look at the second largest size. It’s the Realle – in other words the Royal.

Until the end of the seventeenth century, most of the paper used in the UK was imported, and with the paper came the European paper sizes. A list of paper which was offered to the Oxford University Press in 1674, consists of the four Bologna sizes: Imperial, Royal, Median and Chancery, a.k.a Recute; along with three new English sizes: Crown, Medium and Pott. Ah Pott, what a missed opportunity.

So Crown was invented in the UK, at some point. But how did the Royal arise in Bologna? The answer is that a medieval Royal sheet is very close to an Arab paper size named – I suspect by academics further down the line – the half 1337 Damascus.

So then we have to ask, what made the 1337 Damascus what it was? And the answer is goats. Arab paper sizes were derived from earlier parchment sizes. And the ratio* of the Royal’s long edge to short is exactly what you want in order to get as much parchment as you can from a single goat skin.

So there you go. Royal posters are determined, in the end, by the shape of your goat. Bet you didn’t see that coming.

*Really, so much of paper history turns out to be about ratios. I’ve left most of it out here, but it’s worth noting that all the Bologna paper sizes are very much like our current A4 system. If you fold them in half, the ratio between their long and short sides remain the same. Clever, eh.