When Kenneth Clark set up Recording Britain in 1939, the idea was to capture the spirit and atmosphere of ‘typical’ Britain*, hence the use of watercolour rather than photography, because that gave an atmosphere, not just a factual summary. The urgency came from the war – who knew what of the nation would survive the bombs or occupation.

But the scheme was also looking further ahead, aware that development was also a threat. One of the categories for recording was ‘Fine tracts of landscapes which are likely to be spoiled by building developments.’ In this they were prescient, but in fact it was larger towns and cities which suffered most. And the danger was not from housing, but from roads.

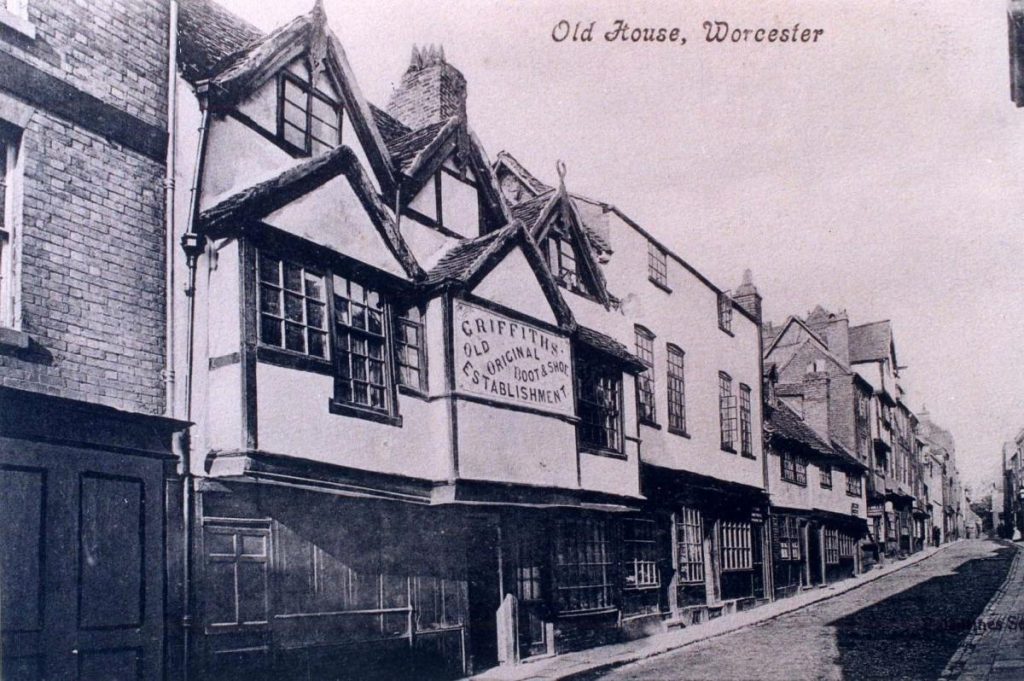

In 1940, Lich Street in Worcester was recorded by the artist Raymond Cowern, who managed to combine producing watercolours for the picture with being an army intelligence officer.

His picture does not glamourise the street, with the telegraph pole leaning in and the dustbins ranged down the side waiting to be collected. The focus is the Old Deanery, which was old and quaint enough to have been featured on postcards.

But this was not enough to save it, nor the rest of the medieval street, nor the only remaining medieval lychgate in the country, through which coffins had been brought to the graveyard and which had a shelf down one side so that the bearers could rest their load for a moment.

All were demolished to make way for a new road, a roundabout and a shopping centre. Its concrete replacement of sleek glass fronted shops and pedestrian arcades, with a sleek blue-glazed modernist hotel sat above was named the Lychgate Centre, the name all that remained of the site.

Lest we get too sentimental straight away, this did make sense at the time. The future was heading towards us – in a car with chrome trim – and we needed the architecture to meet it. My family come from Worcester, and we went round this roundabout on every visit. I thought the Giffard hotel looked impossibly glamorous, like something from Thunderbirds, but we never went in. It was only for weddings and posh people.

Having said that, this kind of development would never happen again – the buildings would be saved, the street line preserved and no one in their right mind would drive a main road within twenty metres of a cathedral. In fact, when the roundabout was being upgraded a couple of years ago, the site was excavated by archaeologists, trying to find out more about the history of buildings which had only been demolished within living memory.

I feel slightly guilty about writing this piece. It’s like shooting fish in a barrel; the redevelopment of Worcester has become one of the most notorious post-war pieces of planning that took place and of course it looked more picturesque beforehand, even if most of the old buildings had become close to slums.

At the same time, this obviousness can be instructive. Recording Britain knew that, war or no war, development was going to change the way the country looked for good. But they did not entirely predict how this would happen. The collection contains more than a dozen pictures of Underhill Road near Ditchling in Sussex, which had become a cause celebre just before the war because of a threatened housing development. But the edge of the downland is as bucolic now as it was when pictured, repeatedly, by Charles Knight.

When Raymond Cowern was recording Lich Street, I would be surprised if he thought it in danger, except from the bomber. This is just a piece of typical England, where old and new mingle, the telephone lines dip past Tudor and Georgian roof lines and life goes on, in the form of dustbins and men peering into shop windows, despite the war.

*In fact they meant England: Scotland ended up with its own scheme, Wales was treated as though it was a county and Northern Ireland was ignored entirely.

Recording Britain pictures from the V&A Archive.

You might like these;

https://www.flickr.com/photos/36844288@N00/49479170791/in/photolist-2ityNV8-2ioiFDz-2ii9EfA-2i9Bi29-2i6Rwjm-2hF1uJd-2hDEaSg-2fpeb4u-JeCqe2-nb35Nq-nwR2Fo-mYjFP1-MaywWe-GxJCW9-DzWhcn-bRkwwk-bccJQK-9HrJv5-9odDWv-9f6Y8h

https://www.flickr.com/photos/36844288@N00/49420827606/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/36844288@N00/49538704401/in/photolist-2ityNV8-2ioiFDz-2ii9EfA-2i9Bi29-2i6Rwjm-2hF1uJd-2hDEaSg-2fpeb4u-JeCqe2-nb35Nq-nwR2Fo-mYjFP1-MaywWe-GxJCW9-DzWhcn-bRkwwk-bccJQK-9HrJv5-9odDWv-9f6Y8h/