Modern Tendencies

Reader request day today on Quad Royal. This isn’t something I often do, but Paul Durham has asked for some help from you lot. He’s trying to find as many images as he can of the posters that were issued by Heals for their exhibitions in the Mansard Gallery. This was right at the top of the Heals Building in Tottenham Court Road, and they held exhibitions there from 1917 until the late 1970s.

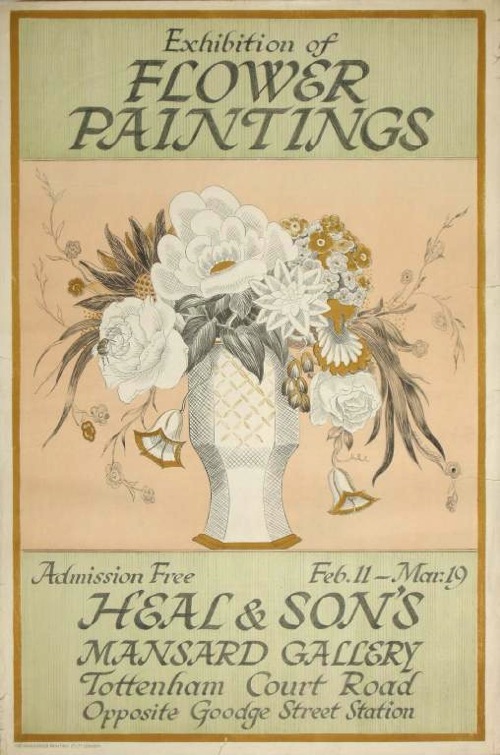

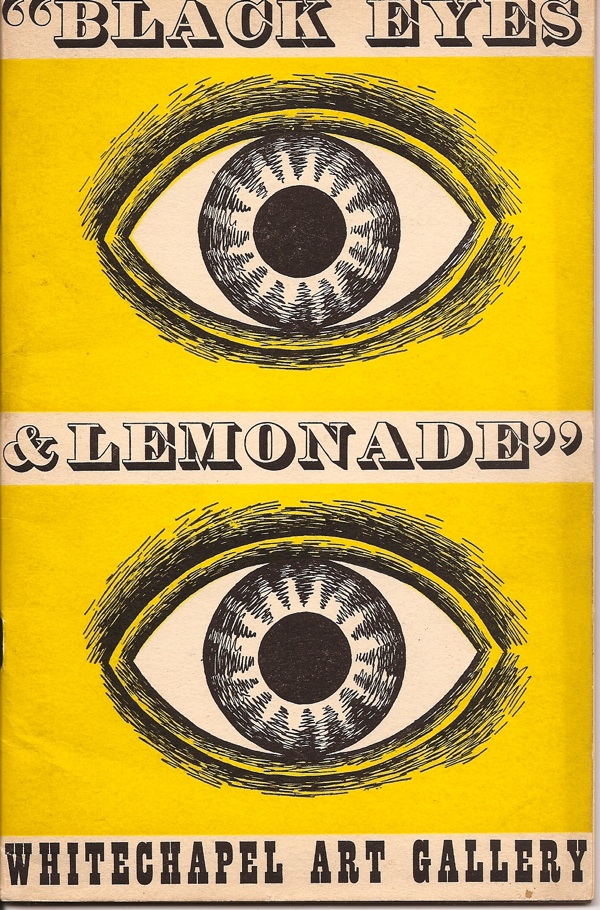

It’s an interesting request on several fronts: partly because the posters are good and aren’t something I have ever covered on here until now, and partly because it doesn’t seem that anyone really knows how many there are and who designed them. Not even Heals can say for sure exactly which exhibitions were held there. So we can, perhaps, add to the sum total of human knowledge. Here’s one I dug up that was auctioned at Onslows a few years ago, by Rhoda Dawson, and for one of their less assertively modern exhibitions.

There’s also the fact that I’m sympathetic to anyone in the grip of a completist collecting mania. These things need to be encouraged. So let’s see what we can do to help.

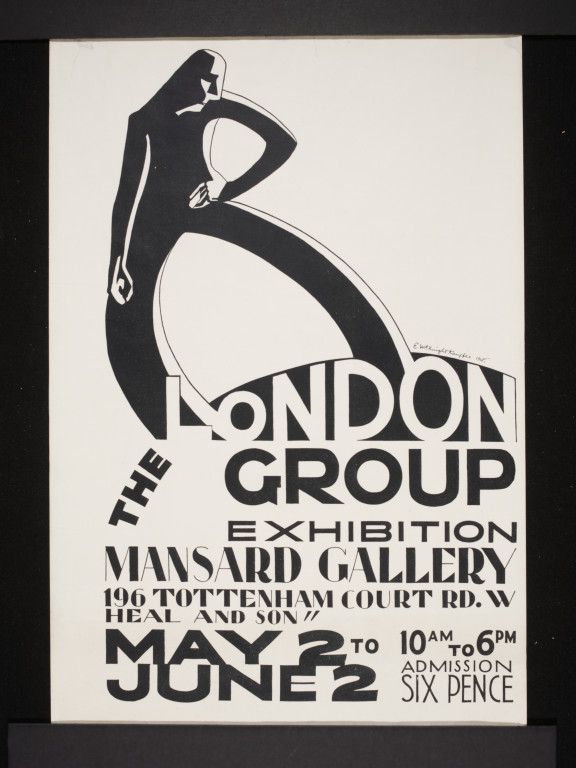

Paul has sent me a few over as starters. This is by McKnight Kauffer from 1918, and is the earliest one he’s managed to track down so far.

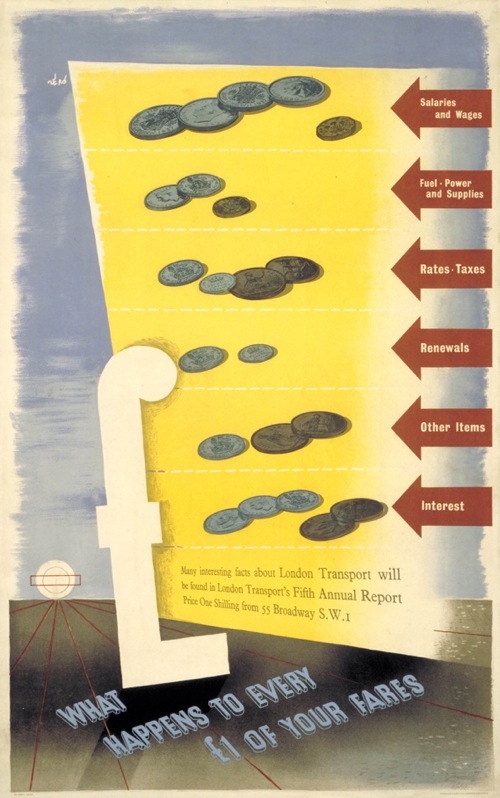

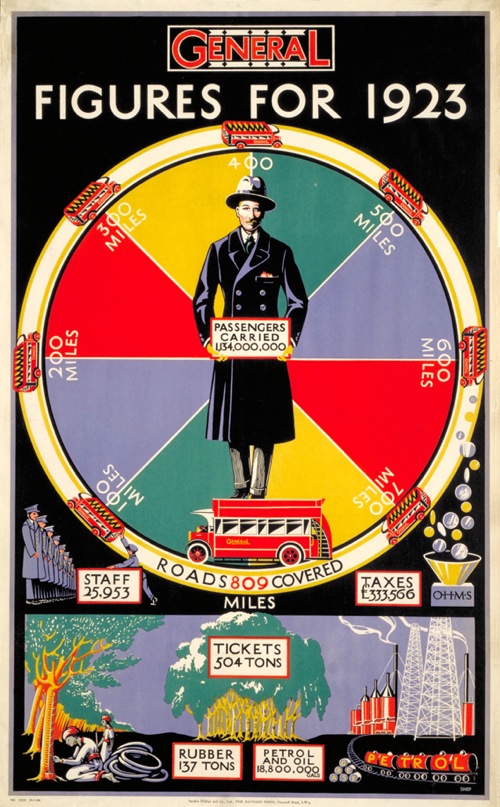

There were earlier exhibitions though. The second one ever, Poster Pictures, in June 1917, displayed the original paintings for many London Transport posters, in aid of prisoners of war in Germany. Which is very interesting as it proves that the dissemination of posters as art wasn’t just limited to what LT themselves put on show.

When I first read about the Mansard Gallery, I thought, oh, art exhibitions at the top of Heals, fair enough. But actually the idea was a bit more interesting than it initially sounds, being as it was part of the great between-the-wars project of making everyone like elitist art. (I’ve posted about this so often that I simply can’t put all the links on; one day I must index this monster).

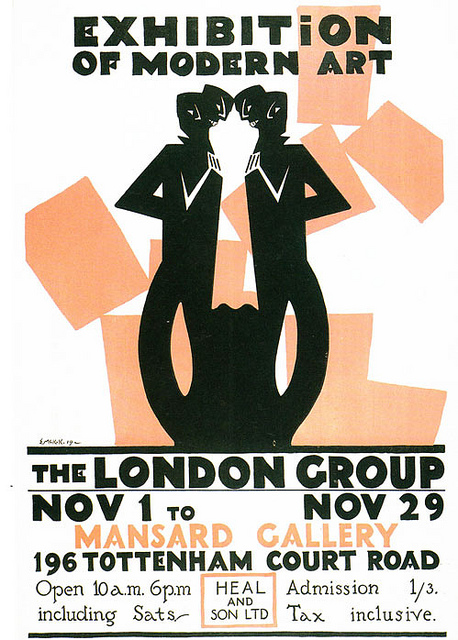

Obviously the Mansard Gallery held art exhibitions, it’s what galleries do, after all. But the aim of having them in a furniture store – and of displaying the art in the first place – was to persuade people buying furnishings that they might benefit from art work as part of the house decorations and how it may work within the home. That’s another McKnight Kauffer below, by the way, from 1918 this time.

Part of me thinks this is all a bit, ‘books do furnish a room’, but that’s probably unfair. Not least because Heals really did want to persuade you that art would improve your home. So much did they want to persuade people of this, that there was not merely a gallery up in the top of the building, but also the Mansard Flat, which was furnished to the very apex of Heals taste, and was used to show how art might work in a domestic setting. Which then makes sense of a picture I have seen (but don’t ask me where) of a McKnight Kauffer London Underground poster being used in a Heals furnishing display. I wish I could find that, as it would tie up all the loose ends quite neatly.

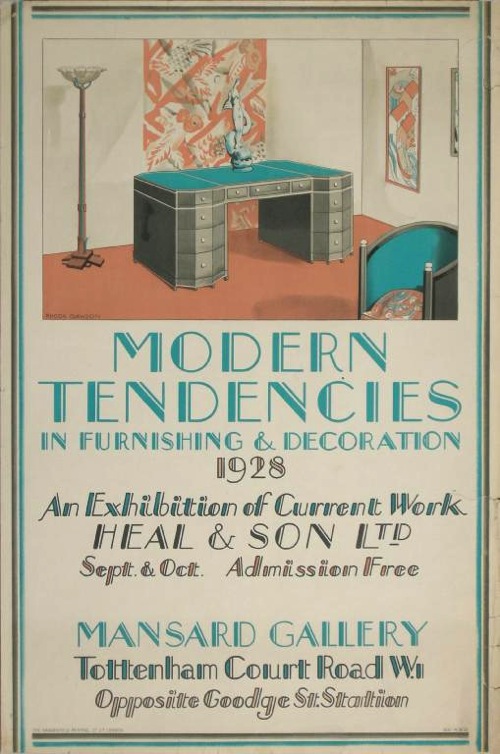

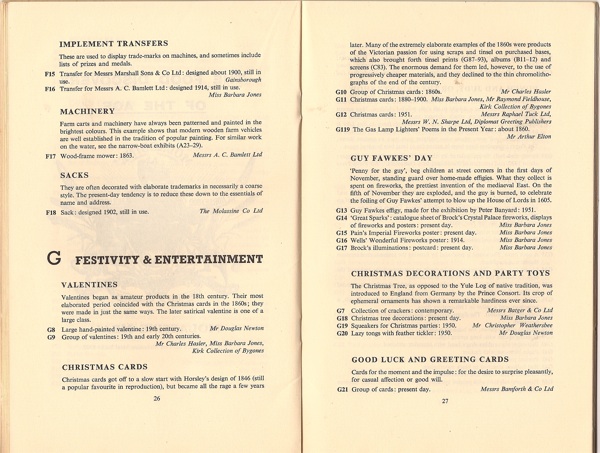

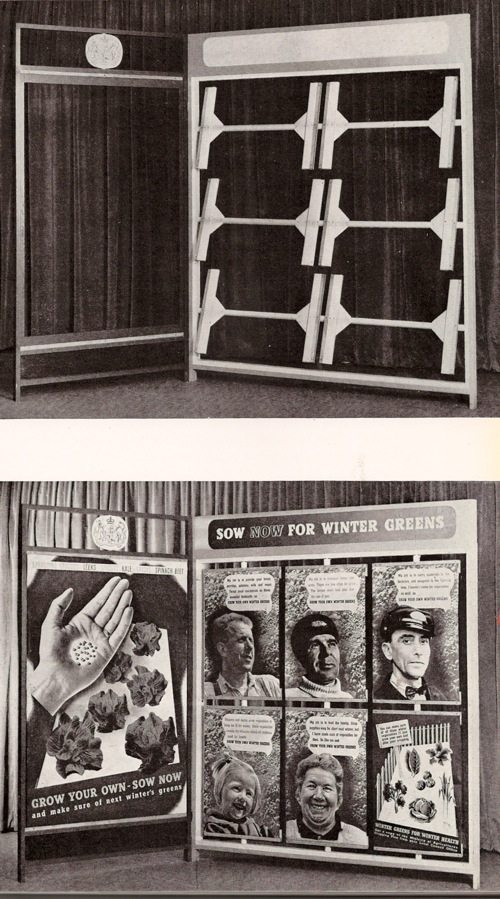

But as you can see from the posters above, the demarcations were nothing like as neat as that; just as art crept into the furniture displays, so did furniture make its way into the gallery. I’d be intrigued to know what furniture too, presumably the stuff that was a bit too advanced to actually sell to the English, even in London. That’s what seems to be on display here; it’s another poster by Rhoda Dawson, from the same lot at Onslows.

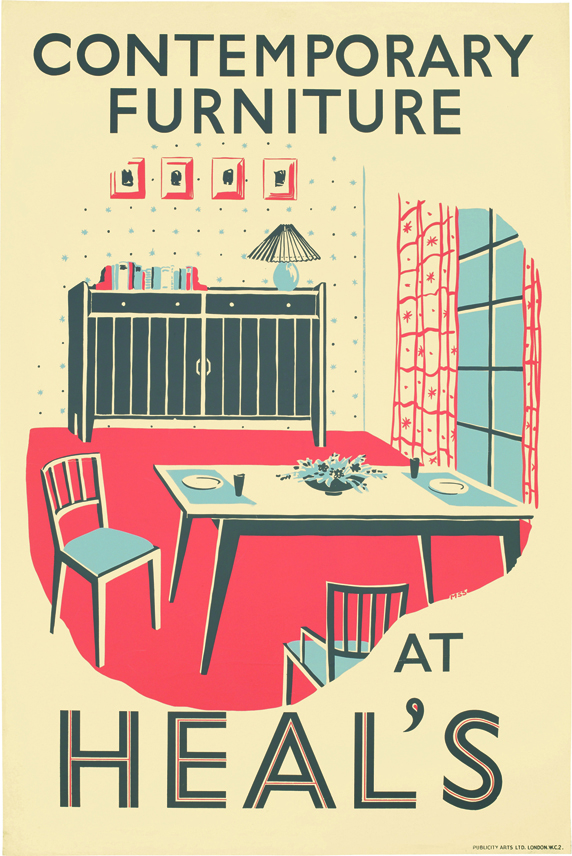

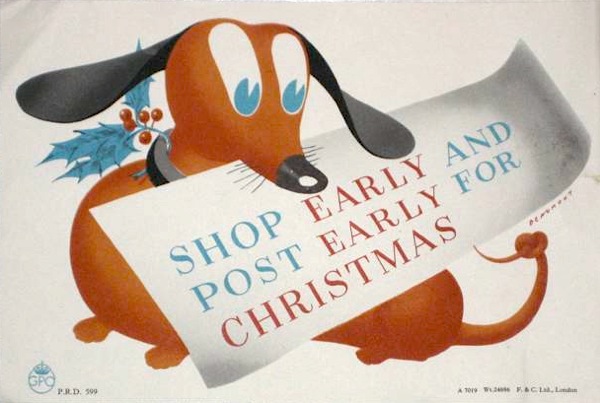

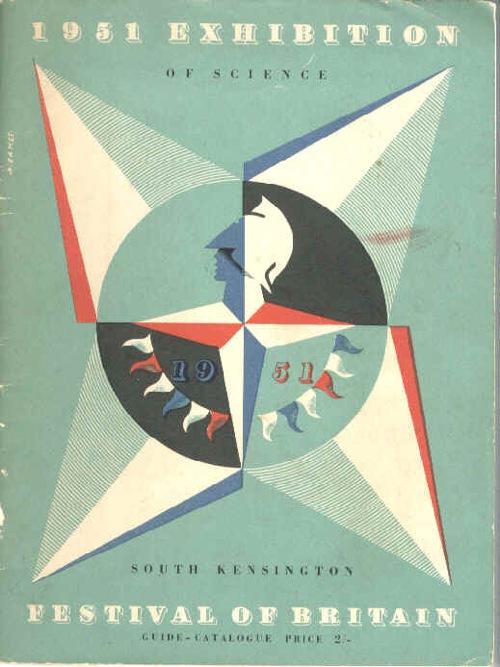

But of course these divisions aren’t so neat and tidy outside of the gallery either, because Heal’s also produced rather good posters for their furniture as well as the gallery. These are rather outside our remit, but then they are so good that I can’t leave them out entirely.

They’re also quite liberally scattered over the web as Heals produced reproductions a few years ago. How did that pass me by?

That however is by the by. Can anyone point me, and more to the purpose Paul, at any more. I have a feeling that there will be more lurking in books and catalogues than there will be out there on the net, so if you know of any, please do let me know. For myself, because I’m interested now, if there are any pictures of the exhibitions, please send them along too.

Addendum:

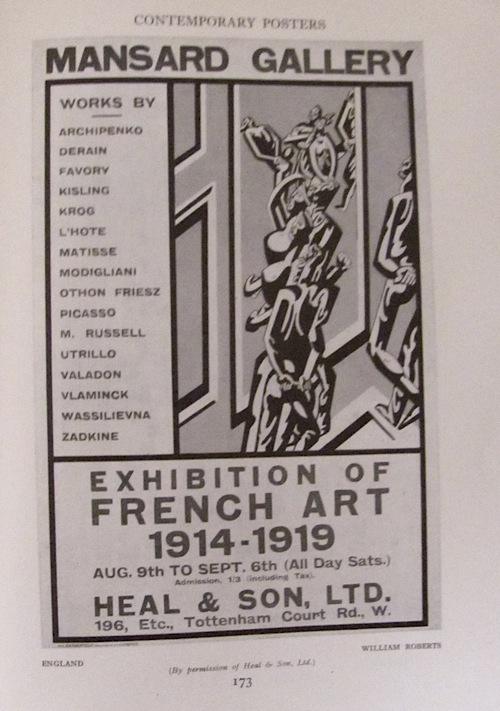

Here’s another one, by William Roberts, which Martin Steenson found in McKnight Kauffer’s Art of the Poster.

Thank you for that one.