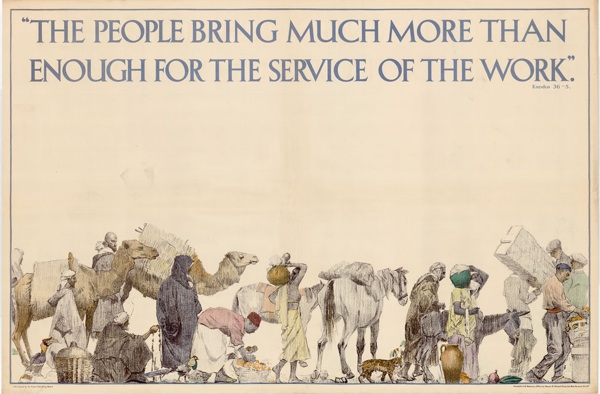

I’m back with the Empire Marketing Board posters once again. In particular this one, which neatly encapsulates the problem of Empire in a single image.

I rather doubt that it was intended to give exactly that message; nonetheless it is rather brilliant.

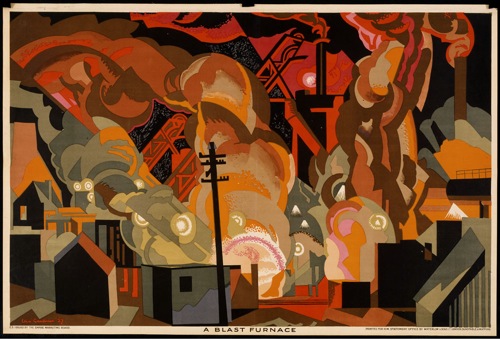

This treat comes from a wholly new archive of Empire Marketing Board output in the National Library and Archives of Canada, which I was introduced to by sometime commenter on the blog, Mike Meredith. It is a treasure chest of things I have not seen before – well over 400 of them in fact, and I haven’t finished sifting through them yet. Here are just a few for starters, these two by Clive Gardiner in a very modern style.

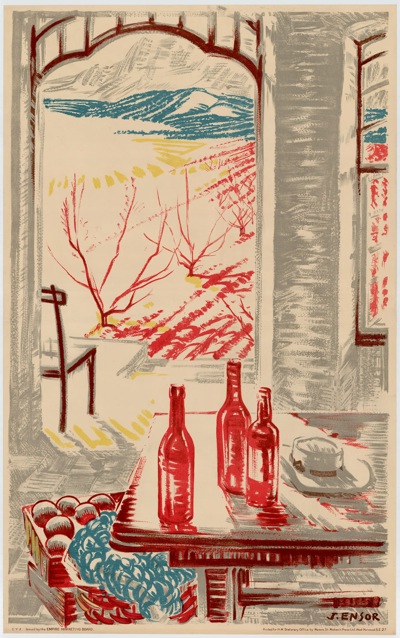

While this John Ensor is modern in a slightly different, almost early-1950s kind of way.

This collection is a reminder that the EMB was not just exhorting the British people to support the Empire, the colonies had to do their bit as well.

Not everything can be a work of art, you know.

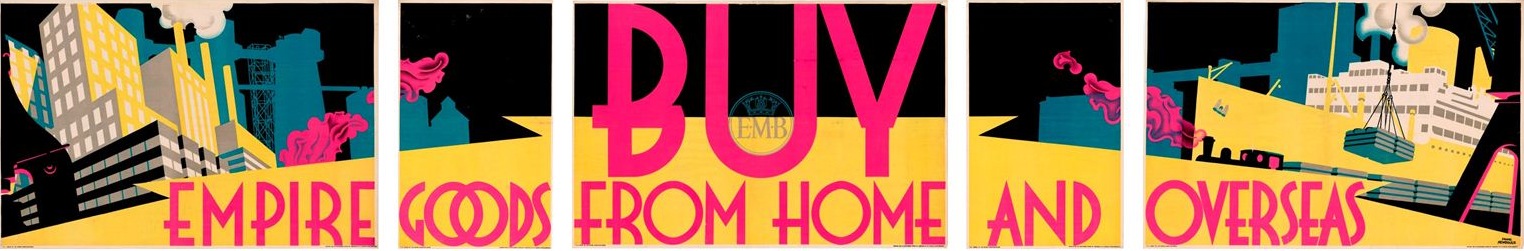

But Mike Meredith hasn’t just been looking through the archives, he has also been doing something rather interesting with these posters. He’s been arranging them as they were meant to be seen.

I’ve mentioned in passing before that the Empire Marketing board had special display stands for their posters. A rather interesting article (about the EMB’s relationship with the Irish Free State) gives a very good description of what these were like. The EMB,

displayed approximately one hundred poster series on specially built wooden frames.Each series featured five different posters:three 60 inch by 40 inch pictorial ones and two smaller posters that carried press messages offering details of the country being promoted or messages advancing imperial trade. The five posters on each frame endorsed a linked theme — for example, fruit from the tropics or the value of import – export trade with Australia. By 1933, poster frames at 1,800 different sites graced 450 British towns

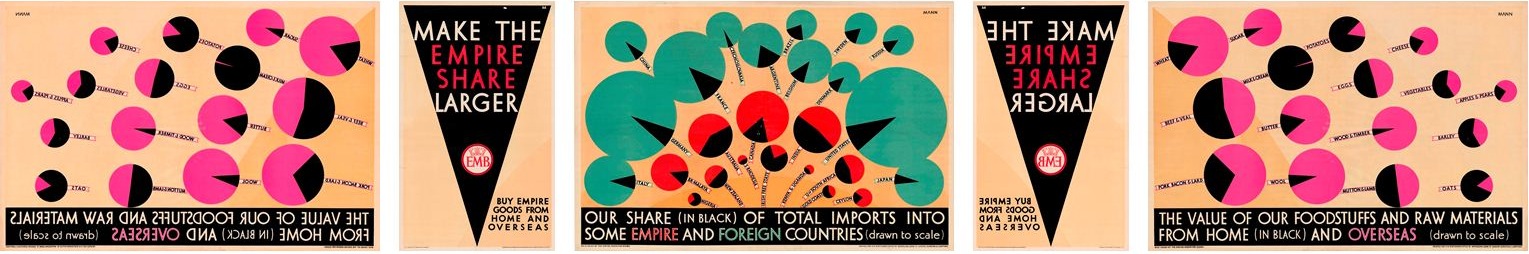

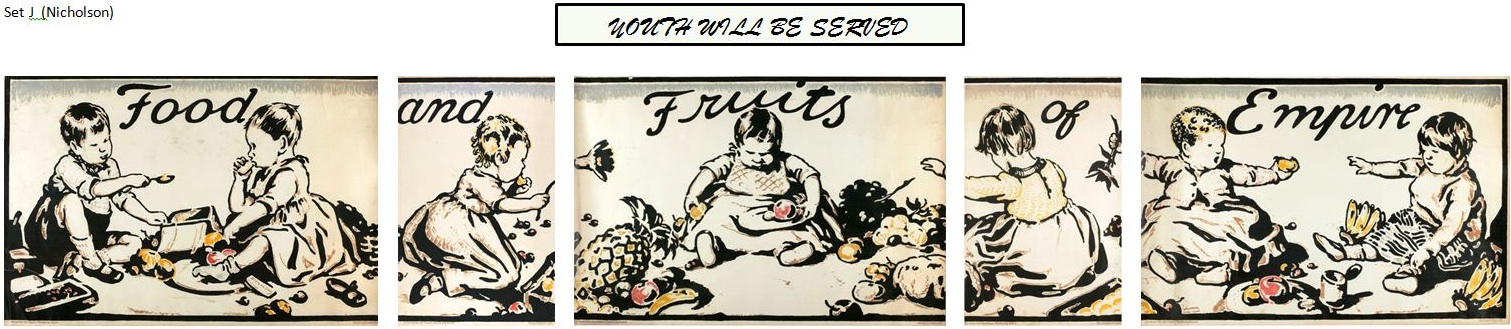

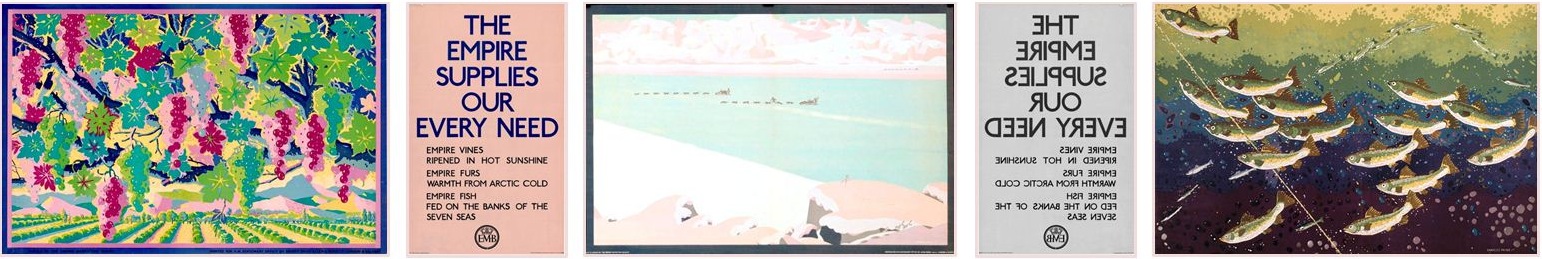

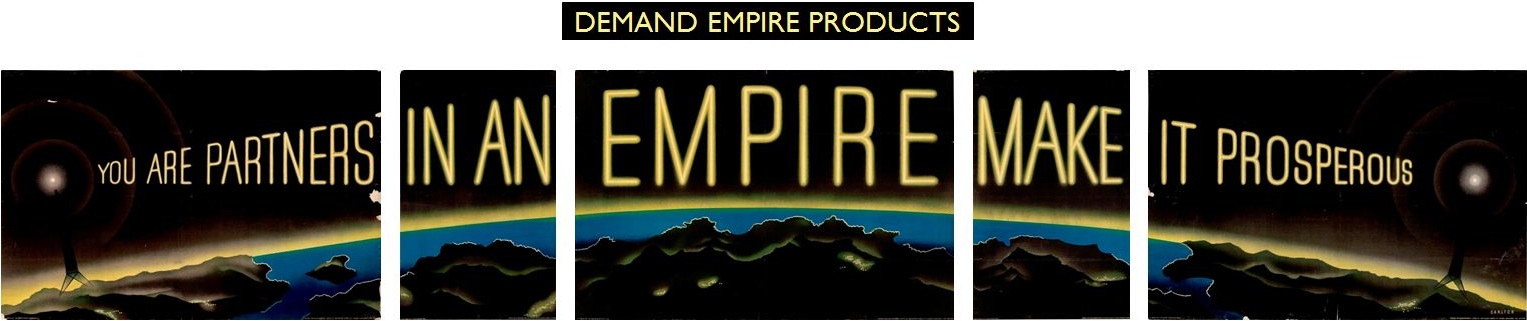

The only thing missing from that description is the title strip which ran across the top. But why should I just tell you about these when I could show you? Because what Mike Meredith has been doing is stitching together these posters from the archives to get a sense of what they would have looked like when they were on display.

Not only is it brilliant to look at, I also think it’s important too. Take a single poster – as I have been doing at the top of this post – and they are quite good. Take a whole set together and they are quite frankly stunning. (Click on the image below to see it at a decent size.)

They must have looked extraordinary on the streets of Britain in the 1930s, like nothing else that could be seen there. Surely not even the most jaded observer of city life would have been able to just let their eyes drift over these posters each time the displays were changed. You would have to stop and stare.

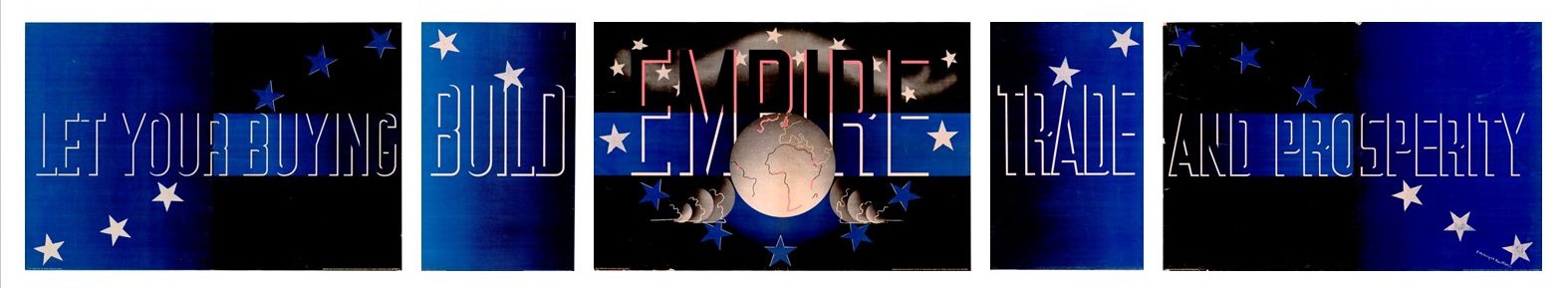

Especially at these McKnight Kauffers, which bring all of the glamour of a Hollywood title sequence straight onto the streets of a British town or city.

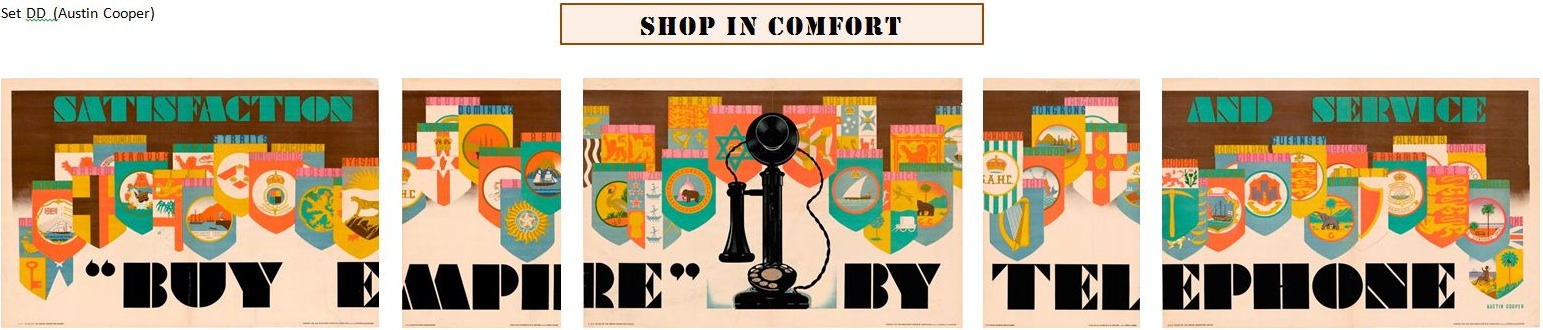

The cinema wasn’t the only referent of modernity, this Austin Cooper set links the old-fashioned Victorian Empire with the excitingly modern telephone.

Displayed like this, even graphs could become dynamic symbols of the modern age.

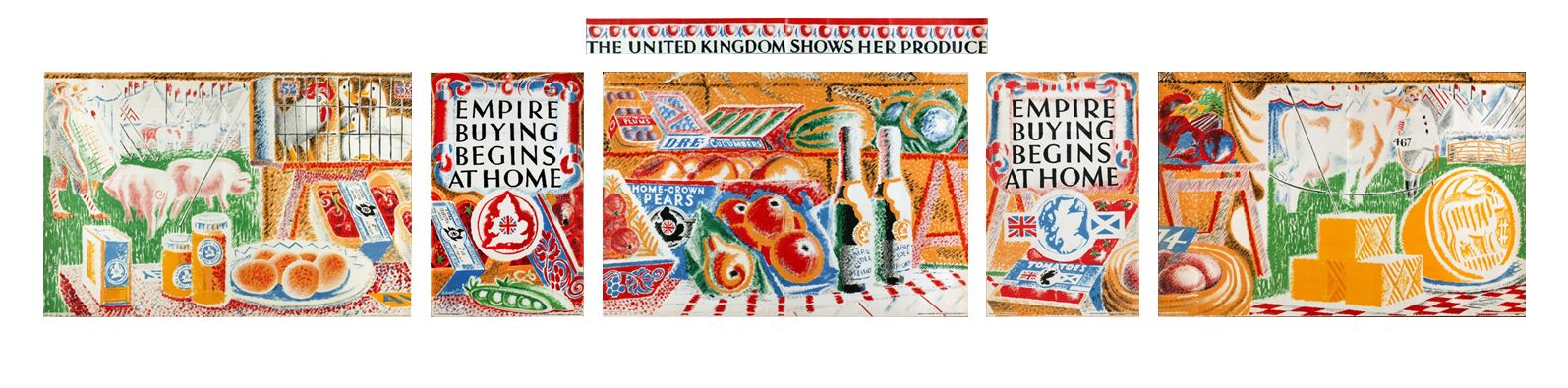

But even the more traditional designs have a very different impact when seen en masse.

This doesn’t just make me rethink the value of the Empire Marketing Board posters, and the ground-breaking nature of the Board’s work – along with its leading man Stephen Tallents. It’s also a reminder that, whenever we look at a poster, it’s essential to remember the context in which it was not only produced, but displayed.

Commercial posters of the 1950s were not only bright and jolly because that was the mood of the times. They were put up against a background of unpainted houses and crumbling war damage, a Britain that was agreed to be grey, dreary and run down. So their bright colours must have looked a thousand times more vibrant against that monochrome streetscape.

And the EMB posters which, on their own, can seem to be a bit like inoffensive railway posters or pieces of art, take on a whole new energy and surprise in their block displays.

Sometimes, we can appreciate a poster by looking at it against the white walls of a gallery as though it was a piece of art. But more often, as is very much the case with these Empire Marketing Board posters, we also lose a lot that way. A poster, or indeed a set of posters, is not a timeless object, but is produced not just in a single moment and place but also for that moment and place as well.

So if we don’t pay attention to that when and where and how, we will never hear much of what that poster might be able to say to us.

I believe you meant James Ensor. Not to be a thorn in your side. I have always enjoyed your posts!

I do mean that, thank you .

Thorns are always very welcome, it stops me from getting sloppy with the facts!

I have much enjoyed reading this article – thank you!

‘John Ensor’ is correct, rather than James. Arthur John Ensor (1905-1995) was born in Wales, and spent much of his life in Canada. He studied art in London at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Art in the 1920s, and from there won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, obtaining a Diploma in Mural Painting. Ensor was a close friend of the artists Thomas Hennell (1903-45) and Clifford Ellis (1907-85), both of whom he met at the Regent Street Poly.

Thank you, that’s really interesting info.

Hello Jessica,

You are correct with the information about John Ensor. I knew him personally for many years. A sweet, charming man with a delightful sense of humour.

Sandra