Sometimes I make promises which turn out to be quite rash.

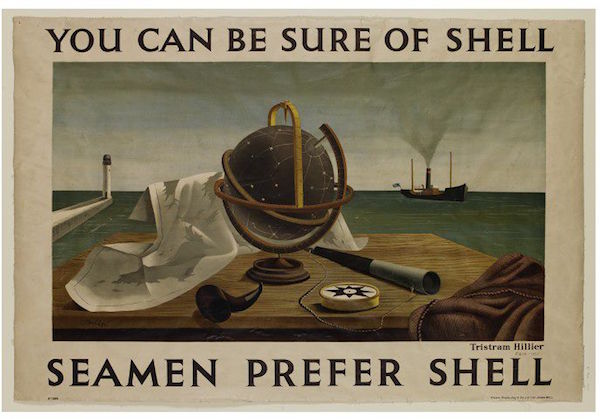

When this poster came up for sale a few weeks ago, I said that I would find out more about both Tristram Hillier and Jezreel’s tower and report back.

In both cases this has turned out to be a more difficult task than I thought. (I do also have a residual bitterness, because we tried to bid on this poster and were thwarted by the internet, and so it went to someone else for only £120, but I shall try not to let this cloud what comes next, even though I am a bit narked by it all.)

I thought Jezreel’s Tower would just be the ruin of some seventeenth century folly. If only. The building is modern, made from steel beams and concrete, while its story turns out to be far more complicated, with cans of worms concealed within other cans of worms, along with eccentricity, delusion and religion. And the Co-op. So what follows here is a very abridged version, with plenty of links to people who will tell you more.

The tower was begun in the late 1880s, by James White, who had become a follower of the prophetess Joanna Southcott (you can read her teachings here if you like – do report back as I haven’t gone that far). White changed his name to James Jershom Jezebel, decided that he was a Messenger of the Lord and set up his own church in Gillingham. This new sect had its headquarters in Gillingham, and combined religious fervour with a certain commercial acumen, as they managed to run several successful businesses in the town, including carpenters, joiners and printers, as well as a dairy, along with a greengrocers in Marylebone.

All of this meant that the sect had enough money to think about a headquarters, and White/Jezreel, bolstered, inevitably, by a vision from God, wanted this to be a grand one. The tower was planned in accordance with the Book of Revelations, although scaled down slightly after intervention by the architects (that must have been an interesting meeting) and the foundation stone laid in 1885.

The building was intended to hold many things, including acres of printing presses to spread the word and a 5,000 seater amphitheatre, along with bakeries, reading rooms and lifts, and the concrete construction was to ensure that the tower survived the conflagration of the Day of Judgement.

But it was never completed; Jezreel himself was dead before the foundations had been finished, and his wife Esther, who took over the sect, died only three years later. Work on the tower never restarted, and the buildings were sold in 1903. The new owners tried to demolish it, but gave up as the building was so solidly built. So what Hillier depicts on the poster, although it looks substantial, is only a part of what was constructed, and an even smaller part of what was planned.

The land and buildings were bought by the C0-op in 1920, who used the basements for a shoe repairing factory. There was also, at some point, a small factory on the site, producing hose clips stamped ‘Jezreel Tower Works.’ The last remaining buildings were demolished as late as 2008.

All of this would be worth telling for its own sake, as a reminder of just how much strangeness lives alongside us in daily life. But it also helps to explain why the tower might have appealed to Hillier. His painting is always informed by a sense of intense oddness in otherwise everyday objects. But as a Catholic schooled by monks at Downside, he also seemed to have an awareness of the closeness of death and judgement. Perhaps. He might just have liked the view.

I’m not sure I want to write much more than that about Hillier himself. Usually the more I find out about someone, the more interesting they become to me. But having read Hillier’s biography, I actually like the painting less. I’m not sure why that is: it turns out that he was enormously successful in the 60s and 70s, producing and selling huge numbers of his odd, humming paintings. And he lived only fifteen or so miles from here, so I can understand his images of these hedges and lanes too. But I still don’t like them.

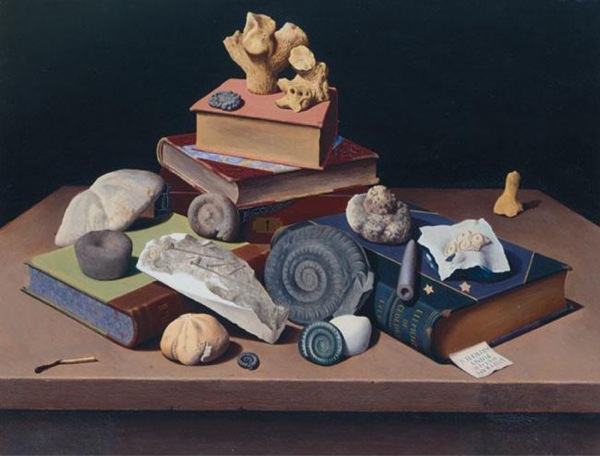

I came out the other end concluding that in fact I liked his commercial work more than anything else he produced. I’ve gone on about the Shell Nature Studies before now.

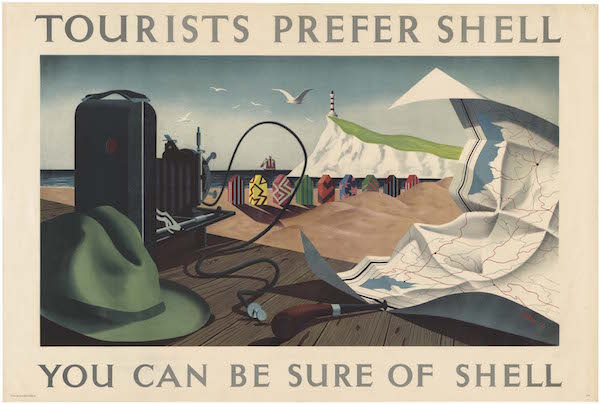

But he also produced a couple more posters for Shell, both of which are wonderful too.

I’m not entirely able to explain why this is the case – and why I am so clearly out of step with the picture buying public who snapped up his works back in the day. It could be that I expect more than just a frisson of surrealism from a painting, and so end up disappointed. But perhaps it is the other way round. Hillier seemed able to bring the same level of oddness to his commercial works as to his fine art. There are many strange artists, but here in the world of posters, he ended up doing something almost unique.

All of which is a bit of a falling note to end on, so to cheer you up, have this. From the splendidly titled series, Why Bring That Up? (why indeed), Pathé News will now explain Jezreel’s Tower.

Interesting stuff, as ever, Crownfolio. England is a weird place

That would be a great title for a blog…