Earlier this week, I made it down to London to take a look at the British Murals and Decorative Painting exhibition, as mentioned a few weeks ago.

I still love this.

Although I have faced up to the fact that we have neither the funds nor a wall space large enough. Mind you, it was tempting; it was starting to look cheap, at least next to the Edward Bawden which, it turns out, was for sale.

For £165,000.

But as ever, exhibitions never appear quite as you expect. Two things really grabbed my attention, and they’re the biggest thing on display and one of the smallest.

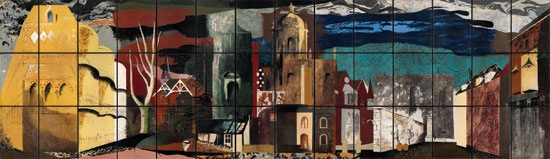

The biggest is the John Piper mural from the Festival of Britain. It’s unimaginably huge. Even on Bond Street they could only find a space that would fit two thirds of its panels.

Its size is also its undoing, because a reproduction condenses it so much that you simply can’t see how good it is. Take this detail, a cupola which is in part from Castle Howard with a bit of the Sheldonian thrown in.

Or even these houses behind Owlpen Manor, which just disappear in a reproduction.

Really it’s brilliant – a contender for one of the best things Piper ever did, and I could have looked at it for hours. And it really, really ought to be in a museum so that everyone gets the chance to do that.

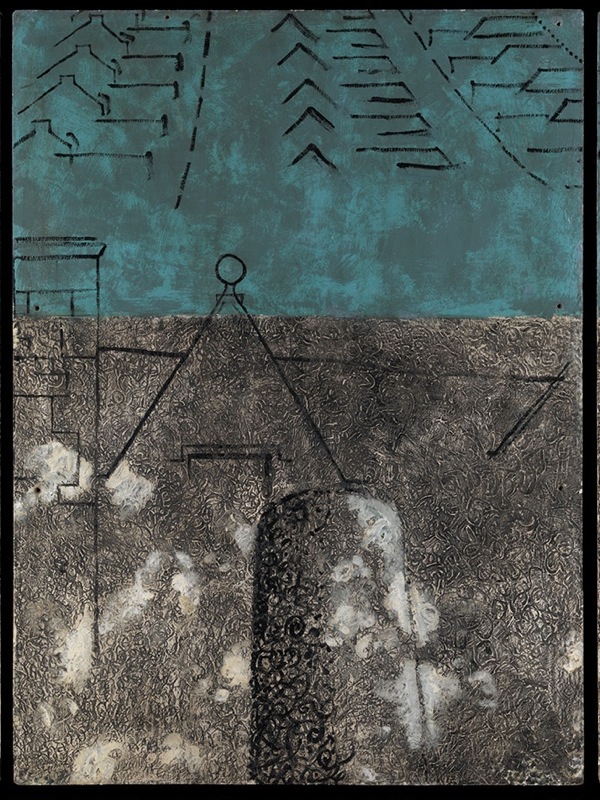

The other object that caught my attention is tiny.

This is a sketch by Kenneth Rowntree for a mural design for the British Restaurant in Acton in 1942. I like it as a piece of design, but I love it even more for what it represents.

The British Restaurants were set up by the Ministry of Food during the Second World War as places where people could get a reasonable meal (well, within the confines of rationing) at a fair price. They were set up in schools, in village halls, and, as Rowntree’s design shows, in churches too. But what absolutely astounds me, and fills me with joy, is that the Ministry of Food decided that it was important that the restaurants were decorated, and not just by anybody, but by some of the leading mural artists of the time.

Here, thanks to the Imperial War Museum, are some bureaucrats, examining a British Restaurant with a view to getting it decorated.

A flick through the book which accompanies the murals exhibition reveals that it wasn’t only Rowntree, a conscientious objector, who worked on the British Restaurants, many other of his contemporaries did too.

There is so much that is good about this scheme, but what I love most is the vision, the sense that even in a world where food and supplies are rationed, where every man and woman is being directed to where they can best support the war effort, art is important. But this isn’t an elitest intention, far from it; this art is designed for the most democratic of public places, it is genuinely art for all.

It’s a spirit that makes me thing that there was a country that I would have liked to live in. I know there were disadvantages, and I probably wouldn’t have liked the bombing and the deprivation, the constant fear of death. But even so, in its pride and its sense of what mattered in life, it’s a far better place than where I find myself living now.

With the Barbara Jones do you think there was originally another panel? The intersection of the bottom of the stairs and the hallway floor looks incomplete. Or did it make sense in the flesh?

I know what you mean looking at it on the screen, but it didn’t strike me that way when I saw it. I think what’s going on there, is that the back skirting joins up, but the nearer edge of the stairs is what looks awkward.

Apparently it came from her studio, so it ought to be complete!

It wasn’t only the visual arts which were brought to the masses in WW2; there were in London, for example, lunchtime concerts, intended for the general public, of classical music by internationally respected musicians. I think that these concerts were free [although I am open to correction on that]. I presume it was all part of the effort to maintain civilian morale.

Yes, absolutely, and I think that the commitment to ‘fine’ art has very much been recognised, along with the increased appetite that the general public apparently had for it during the war. What I find particularly pleasing about this, though, is that it is art integrated into daily life, without much expectation that it will ‘improve people’ in that slightly annoying top-down way, just that everyone deserves to have it around them, not only in Piccadilly but in Acton too.

So brilliant to have you back Quad Royal –

some fabulous and interesting pieces as always …..

thankyou …..

Christine