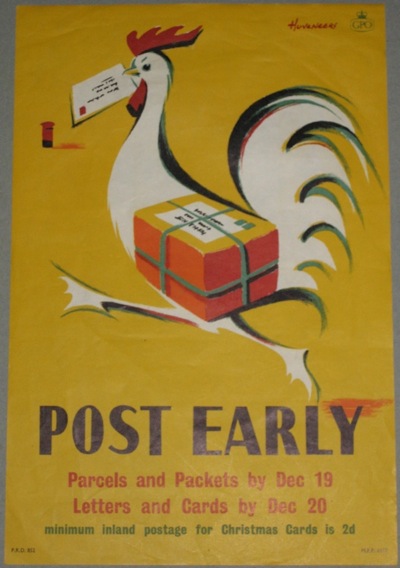

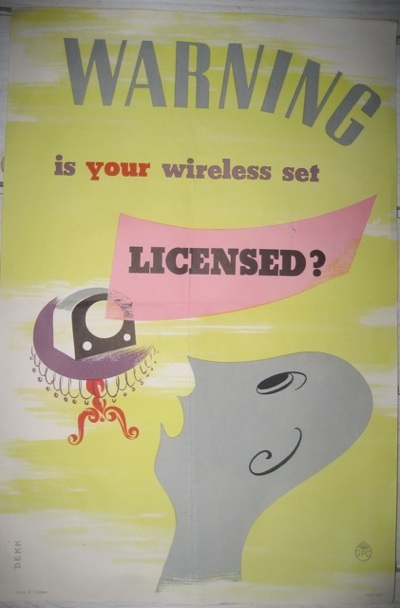

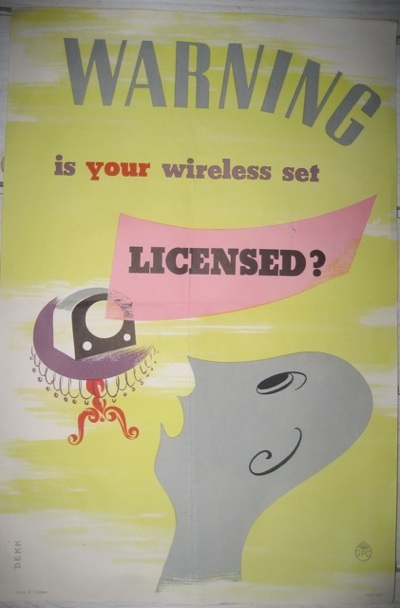

This great little GPO poster (a Crown Folio, naturally) was recently on eBay

as a Buy It Now (for £20, it didn’t last long).

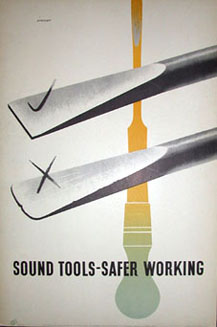

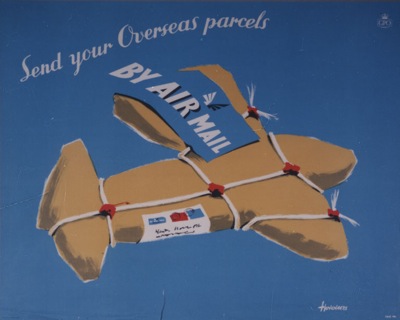

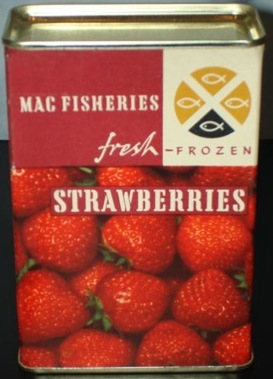

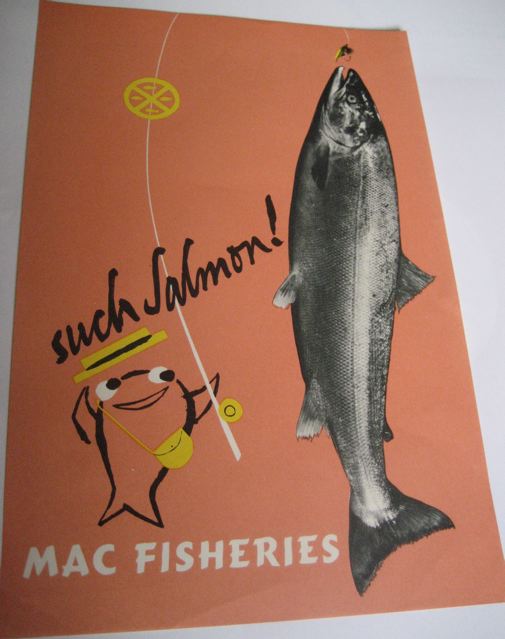

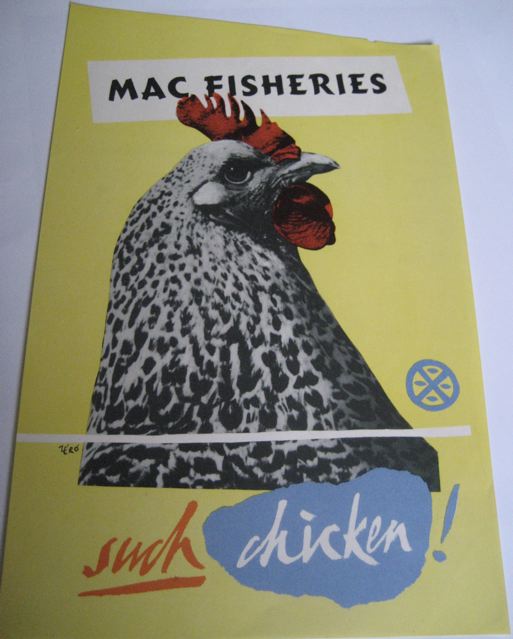

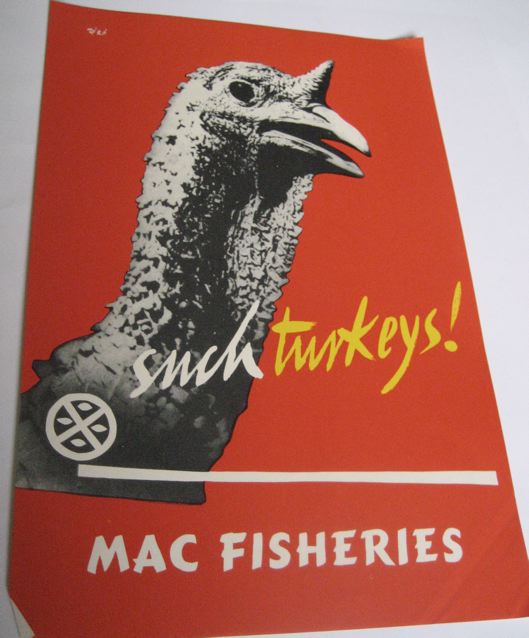

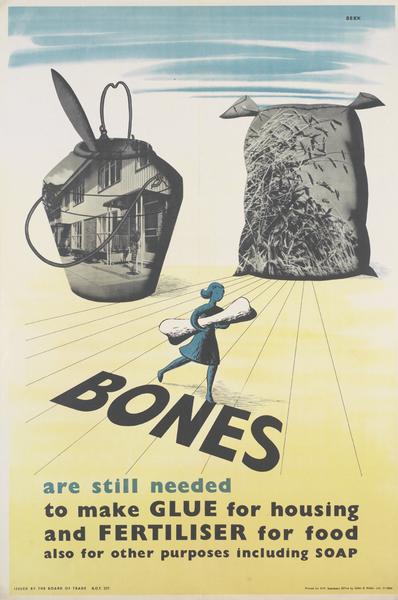

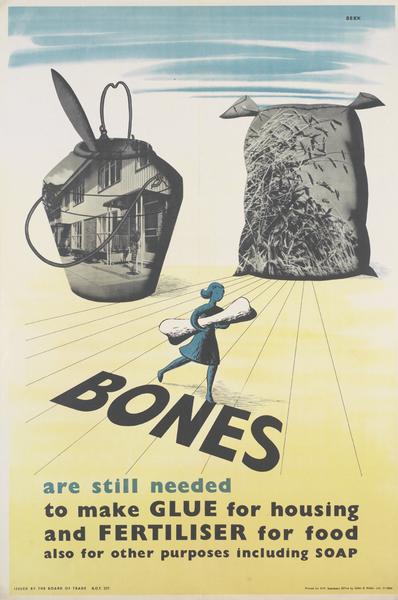

From 1949, it’s by Dorrit Dekk, who, despite designing some iconic COI posters like this one

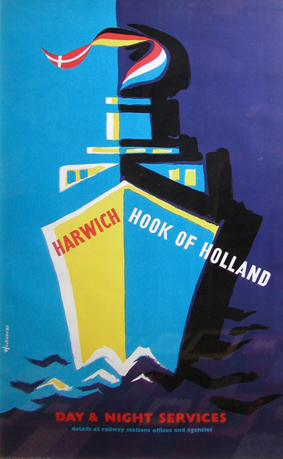

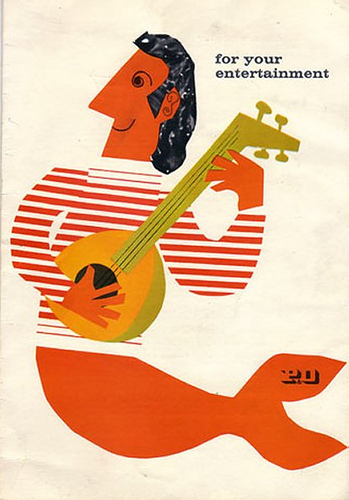

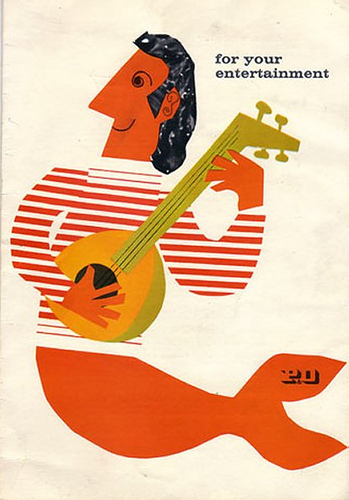

and some very smart later stuff too, such as this P&O menu design

isn’t as well known as she rightly ought to be.

But more than just posting some lovely images of her work (there are plenty more of her later designs on a nice Flickr set here), I also wanted to point you at an interesting, if slightly strange set of interviews with her.

They come from Your Archives, which is an attempt by the National Archives to create some Wiki-style content. The Dekk interview is part of a World War Two artists section, although it’s about the only bit of original content that I’ve managed to find in there. Most of the articles are just standard bios with link to relevant artworks in the archives. Which would be alright if the National Archives had any thumbnail images in there, but they don’t.

There’s a perfectly servicable biography of Dorrit Dekk included, so I won’t repeat what they can perfectly well tell you themselves, but her career included an apprenticeship in the COI under Reginald Mount and Eileen Evans, as well as designing for the Festival of Britain.

Amongst other things, she explains how Reginald Mount gave her the pen-name Dekk:

Now one day, when the printer came back to collect the art work for the first poster I did and I was still finishing it off. He said “Well, you haven’t signed it” and so I said “I hadn’t thought about signing it.” And then I had a problem. I said “My married name was Klatzow” – which was a Russian name – and in those days a foreign name would have been difficult and unpronounceable. K-L-A-T-Z-O-W: that would be fashionable now! I didn’t like my maiden name, Fuhrmann. So then, Reggie said “So what are your initials?” and I said “DKK” and so he said “There you are: DKK. We put in the E” and Dekk was a good thing because was easy to understand on the telephone. It was not like having to spell Klatzow or Fuhrmann and, written down, it was good for signing. And it looked foreign which was an advantage – I didn’t pretend to be English – but at least it sounded possible.

And how designing for the Festival of Britain was the fast-track to a career after the war,

…the fantastic thing about the Festival was that you met all the great designers because you always had meetings together: Misha Black and Jimmy Holland – of course I knew him by then – Henrion, Abram Games, everybody! Abram I must have met at one of those meetings. And without the Festival I wouldn’t have been successful – it was like a badge of honour. If you had been a designer for the Festival you had arrived. And I was quite young after all and I had no experience – just those two years at the COI. I mean I was green. And then after the festival, all the jobs came in. It was so easy to get commissions after that because I had met everybody and, if I approached people with my portfolio asking “Can I design anything for you?” I got new commissions.

But large swathes of the interview are dull, if not frankly borderline surreal. Instead of asking her more about what working in the C.O.I was like, or about her later work, the questions are about gouache, Tippex and paper quality instead.

A bit of digging around reveals that the purpose of the whole project (and hence the interview) is for conservators at the National Archives to

identify the paint and drawing materials (media) used by artists for propaganda artwork and illustrations during the Second World War.

Which I am sure is terribly useful for them, but a gigantic missed opportunity for the rest of us. Although I suppose that the lesson is that I shouldn’t rely on the journalistic nous of archivists and conservators if I want to find out about designers and their work.

Dorrit Dekk is still alive and working, incidentally. And if you want to buy one of her recent collages, they are available on eBay right now.