On Display

Having already written in praise of the ephemeral last week, it’s time to explore some more things that can never be recreated.

I ordered this book ages ago, but it arrived just before Christmas after a slow sea crossing of the Atlantic.

The wait was worthwhile, because it is full of wonderful things, even if, sadly, the cover is the only bit of colour there is.

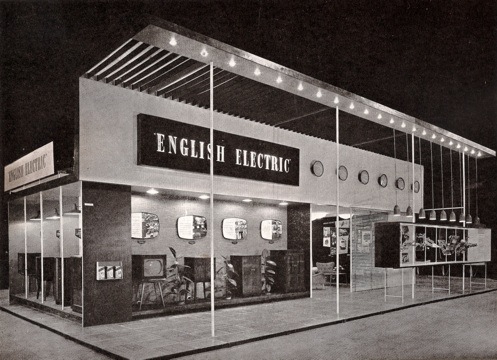

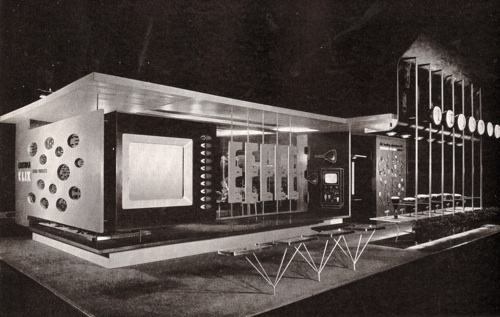

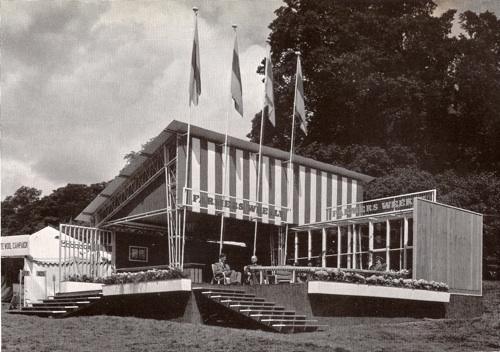

The book covers the full range of display and design, ranging from grand stands at trade shows, like this one for English Electric at the Radio Show at Olympia,

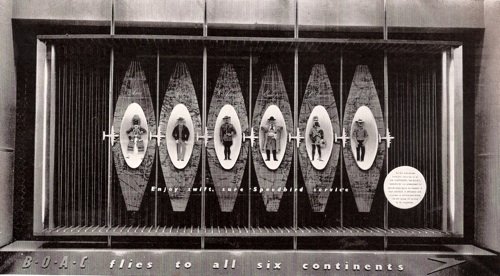

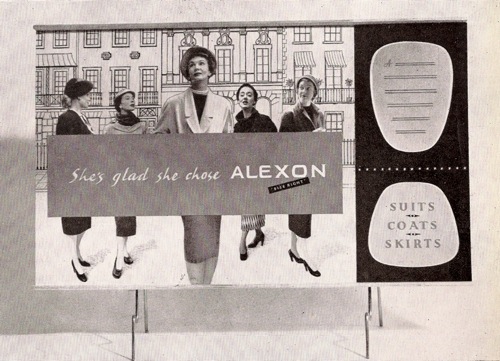

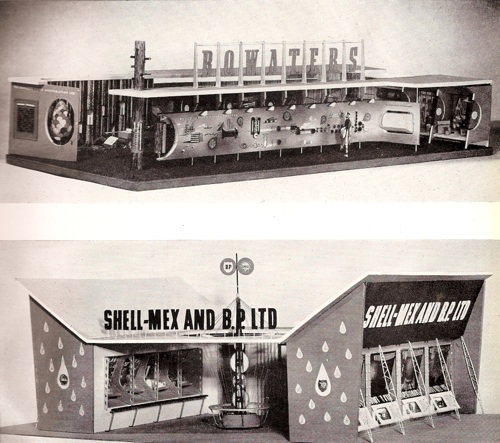

to small portable displays and shop windows.

In addition, there’s plenty of practical advice too, with examples of Pick’s own models for his designs – this one intended for shop windows. He’ll even tell you what glue he used to keep a particularly difficult model together.

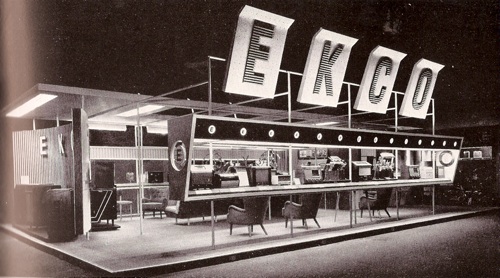

But it’s the exhibition stands I love the best. This is another one from the Radio Show, for a manufacturer of wireless components.

This love isn’t just about a wallowing in ephemeral nostalgia on my part, I also think that the exhibition stands are architecturally important, and too often forgotten.

Pick’s book was published in 1957, at a time when British architecture was only just getting on its feet again after the war. Although a great deal of buildings were being built, houses and flats in particular, the pressures of wartime reconstruction meant that they were mass-produced and kept simple as a result. Almost everything being built was commissioned by governments and local authorities, with private building licences almost impossible to procure, so the scope for architectural innovation was very limited indeed.

Schools were almost the only buildings which allowed for any kind of experimentation, and even this was constrained by the limited materials available, along with the pressure for quick and low-cost rebuilding of war damage. This is Great Barr School in Birmingham, finished in 1958.

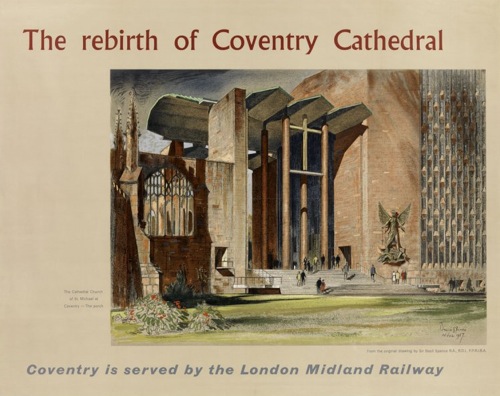

All of which meant that the architecture of the first half of the decade (what tends to be called ‘The Festival Style’) never really got built. By the time that less urgent, more extravagant buildings were being commissioned, the architectural fashion had changed, and Brutalism was coming to the fore. It’s been said that Coventry Cathedral (commissioned n 1951 but only finished in 1962) is one of the few buildings outside the South Bank to be a full expression of the style. Certainly it was seen as old-fashioned even before it was completed.

Although, I personally do have to nominate the Toast Rack building in Manchester as another classic in the style, even if Pevsner calls it the first Pop building ever.

This used to house the Domestic Science College, and thus also had the fried egg building next door.

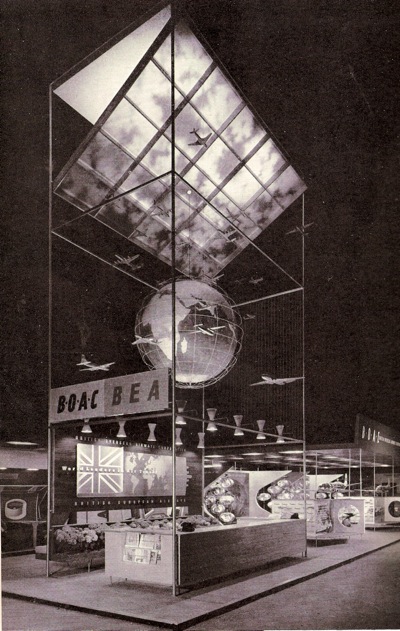

Arguments about the precise number aside, the fact that there are so few of these huildings is why the exhibition stands are worth looking at. Because for the first five years of the 1950s, perhaps even longer, exhibition design was the main expression of cutting-edge architectural taste in Britain.

These stands are not buildings, they never will be, and often they were designed by different people, exhibition designers rather than architects. But they are still among the best expressions of the style of the early and mid 1950s that were ever built, and perhaps all the more exuberant because that architectural imagination simply couldn’t be channelled anywhere else.

Beverley Pick, in his book, is mostly concerned with the design process and mechanics of display rather than the theory, but even he acknowledges that architecture and exhibition design were very intermingled at this point.

In the years after the war, many architects, forced by building restrictions to devote much of their time to exhibition work, by necessity, acquired valuable training in display and presentation. Conversely, display designers, entrusted by their clients with the responsibility of producing their exhibition stands, became well versed in architectural and structural matters.

This is also a reminder that Pick was just one of many designers working in the field. His book only illustrates his own work, but there are plenty more to be found (and goodness only knows I have spent enough time poring over them) in the Designers in Britain series. I particularly love this Farmers’ Weekly stand by Misha Black and Alexander Gibson from about 1950.

This Robin Day design for ECKO dates from about the same year too.

Day also did this ICI pavilion for the Royal Agricultural Show in 1955 or 1956; here the spindly festival style is developing into something sleeker and a bit closer to International Modernism.

I would like to live in this as my house please, with a giant Quad Royal logo towering over the roof.

More seriously, I am really surprised that more attention hasn’t been paid to these exhibition designs, however ephemeral they were. The start of the 1950s – and indeed what is seen as the birth of serious design at this time – is always constructed in terms of exhibitions: Britain Can Make It in 1946 (below), and then of course the Festival of Britain itself in 1951.

Both of these exhibitions are very thoroughly documented, which does help. But all sorts of exhibitions on every scale continued throughout the decade and, mostly, their design has been completely ignored.

This amnesia goes back in time, because a lot of pent-up architectural design was being channelled into exhibition design during the war as well. Here are a couple of rather striking Army exhibitions.

The one above is in Cardiff in 1944, that below on the site of the bombed-out John Lewis department store on Oxford Street a year earlier.

It’s clear that the Festival of Britain style was already in the making during the war, rather than springing out of nowhere on the South Bank.

As well as the big budget extravaganzas, there were smaller ones too, many of which were held at Charing Cross Station (did they tour in the provinces after, or was the newspaper coverage enough I wonder?)

Again, the wartime exhibitions are also a subject which has not been much covered as far as I can tell (and if I’ve missed something please do let me know). All I’ve found so far is this article, and the fact that it was produced as part of a Henry Moore Institute Study Day about Sculpture in the Home shows just how much the subject has slipped between the cracks of different disciplines. It’s a shame for what seems to me to be a really important piece of the design history of Britain. There’s a lost architectural story to be told out there for the telling, if only we can be bothered to look in different places to find it.