I’ve never written about the Keep Calm and Carry On poster on here until now, mainly because the internet is already thoroughly pock-marked with its image and the story done to death, so I was bored of the whole thing before this blog had even begun (and rather assumed that everyone else was too). But I’ve been delving into the history of World War Two posters recently, and rather to my surprise have discovered that a whole chunk of its history – and to my mind the most interesting part – never gets told.

Here it is then, exhibit A, Keep Calm and Carry On.

This is actually the original poster, as produced by the Ministry of Information in 1939. Most of the copies that are around today, not only on posters but also on everything from soap to golf balls (does the world really need this, I am forced to ask) have in fact been reversioned from the original and thus look slightly different.

And if you go and look on eBay (which I wouldn’t actually advise) you can find versions where the type has been bastardised even further from the original, but I don’t want to give these ones the oxygen of publicity.

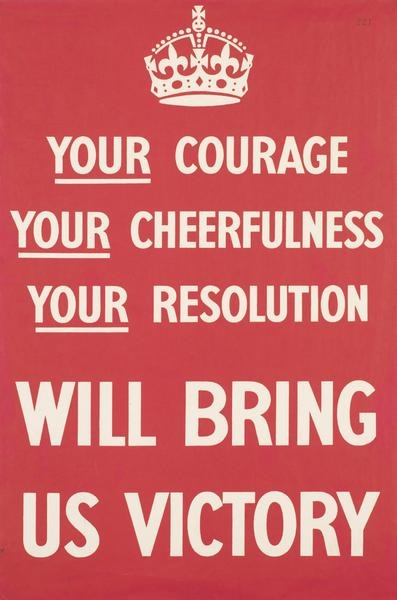

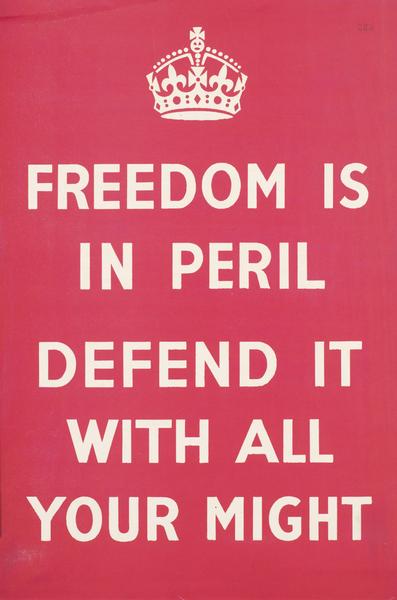

The backstory, as repeated all over the interweb in very similar terms, goes like this. In 1939, with war looming, the Ministry of Information commissioned three posters with the aim of reassuring the British public when the inevitable came. They were meant to be messages from the King to his people, and the three slogans were Your Courage, Your Cheerfulness, Your Resolution, Will Bring Us Victory, Freedom Is In Peril and, of course, Keep Calm and Carry On. Hundreds of thousands were printed, and the first two were plastered all over the country in their hundreds and thousands as soon as war was declared. But the third – Keep Calm – was held back in the case of invasion. This never came, and the poster was eventually pulped and forgotten. Until in 2000 a single copy turned up in a box of books at Barter Books in Alnwick. The owners framed it, and then were asked about it so much that they reprinted a few copies. The rest I think you know.

Now were I to be picky (which I’m going to be, because it’s fun) there are a couple of holes in this story. To start with, the posters weren’t designed by the Ministry of Information, because that didn’t exist until the day after war was declared. The government was in a tricky situation as war became inevitable. Although they knew that propaganda would be a vital part of the war, particularly as they would be fighting an enemy with a slick and established propaganda machine of its own, they were equally aware that any Ministry of Information would be very unpopular with the public. So the plans for the MoI were set up in complete secrecy, and the posters were commissioned by the Home Publicity Committee of a department which didn’t actually exist yet.

What’s more, Keep Calm and Carry On wasn’t designed in case of invasion – when it was commissioned the Germans were hundreds of miles across Europe, and few people imagined that they would be on the coast of the English Channel at any point in the future. What they did predict was that the start of the war would lead to a massive bombing campaign that would destabilise the country and shatter national morale. That’s why people would need to Keep Calm and Carry On, and that’s the real story behind this poster – and why it was never used.

Because although people know that Keep Calm and Carry On was created as part of a campaign of posters, what is never said (and I find it intriguing that it isn’t) is that this was a massive and thundering turkey of a failure. The two posters which were displayed – Your Courage and Freedom Is In Peril – were ridiculed by the press, criticised in the House of Commons and mostly disregarded by the public on the ground that they didn’t really know what they were meant to do. All of which makes Keep Calm’s success, fifty years on, even more remarkable.

So what was wrong with these posters ? Most of the criticism was of the Your Courage slogan, which people didn’t really understand (one complaint being that most people associated resolutions only with the New Year) and which wasn’t catchy enough to be memorable. More worryingly, some people (like Mass Observation) saw the idea that Your Courage would bring Us Victory meant that the general mass of the people would be making a sacrifice on behalf of the upper classes, who would reap the real benefits. This evoked memories of the last war, where many people felt that ordinary soldiers had suffered while the generals had got off scot free, which wasn’t a particularly good set of associations to be revisiting at the start of another conflict.

One of the other facts about these posters which is often repeated is that the phrase Your Courage was thought up by a career civil servant called Sydney Waterfield. The implied story here is that the poster was the creation of exactly what people had perceived in the slogan, an out of touch ruling class who had no idea what ordinary British people thought or felt (with the further implication that one of the good results of World War Two was that, as a democratising force, it put a stop to This Kind of Posh Thing). There is a grain of truth in all this, as the MoI floundered for a couple of years before it began to work well and at one point, amusingly, its Home Publicity was co-ordinated by Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery and Harold Nicholson, husband of Vita Sackville-West. It’s hard to imagine two people further removed from ordinary life. But in the case of Your Courage, it may have been thought up by a civil servant, but it had also been approved by a committee which included representatives from two of the big advertising agencies of the time, S H Benson and Odhams, so someone should probably have known better.

But that’s applying hindsight to the problem, because the real flaw with the posters was that they were designed for a situation which never actually happened. Almost all the planning for World War Two worked from one key assumption, which was that the start of war would immediately lead to wave after wave of bombing hitting the United Kingdom. This would not only cause destruction and casualties on a massive scale, but also hysteria and panic in the general public. Planners worked on the assumption that for every physical injury there would be three psychiatric cases, leading to three or four million cases in the first six months of the war. But when war was declared, the bombers never came. (Nor, as it turned out did the neurosis; in fact psychiatric admissions actually decreased during the Blitz). So the posters were designed to soothe the shattered nerves of a terrified population. Unfortunately, when they were displayed in the calm of the Phoney War, they just ended up looking a bit silly.

So Keep Calm and Carry On is not, as I’ve seen it described, “an inspiring poster which speaks to us across the ages”; instead it’s the forgotten remnant of a rather spectacular failure, a failure of planning, of understanding, but mainly just a failure caused by events. Although its modern success has lead to some versions which inadvertently bring up that history.

I think that’s a much more interesting story than the anodyne set of facts which tends to be repeated on the internet. What’s more there is no reason why the story shouldn’t be told – almost all the histories reference Dr Bex Lewis’s thorough thesis on World War Two posters, which contains pretty much all of the information I’ve put in up there (and plenty more besides, including a blog of all of the misguided uses to which it has subsequently been put). So why don’t people want to tell this story? I wonder whether, just as there is a myth of the Blitz, which is that everyone kept calm and carried on, there is also a myth of the Home Front Poster, which is that they were all uplifting and inspiring from the very start, and so people were always uplifted and inspired rather than bored and cross and irritated with them (as they were). And we wouldn’t want the facts to get in the way of that.

Yesterday someone showed me a book entitled, “British Posters of the Second World War” published by the Imperial War Museum last year. I didn’t get a chance to have a good look but from what I was told it sounds like they include the above version of the Keep Calm story.

The book contains biographies of a few artists,eg.FHK Henrion. Can’t remember the others. Not sure if it adds anything new. I’ll have to add it to my Christmas list to find out!

I also noticed that they dated your wonderful Turn Over a New Leaf poster to c.1942. (Some people are obviously better at searching eBay than me!)

Thanks for the comments! And yes, I think we do idealise aspects of the Second World War, but it’s something I’ve only just really started to think about, but I may well post about it in the next few weeks as I think – at least with regard to the posters – it’s well worth exploring.

I think we have an earlier version of that book (at least we have an IWM book with lots of useful biogs which did have one or two additional facts not found elsewhere), so they’ve probably reversioned it one way or another. I will summon it up and investigate it.

We aren’t very good at searching eBay either, it seems, as it was Shelf Appeal wot found it. A very odd kind of stealth listing, though, because it had all the right words in it, but somehow failed to come up on any searches. Which did at least make it affordable…

The constant reproduction of this image makes the original appear more significant than it actually was. No serious commentary on British propaganda suggests anything but that all these posters were a resounding flop.

The first efforts at propaganda were based on the idea that “ordinary” people would simply capitulate. The reasons for this are to do with the consistent overstatement of the efficiency of air-attack and also to do with a “moral-fibre” class-consciousness that prevailed amongst the social and political elite.

The best account of all this is Angus Calder’s “Myth of the Blitz” (1992), which unpicks how the British war experience of class solidarity and stoicism (keeping calm and carrying on) was assembled retrospectively. Calder doesn’t really account for poster propaganda specifically – it’s just one part of his story.

The general background politics of the early-war can be got from George Orwell’s essay – “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Picture Post’s “Plan for Britain,” and Evelyn Waugh’s “Sword of Honour” novels. The films, “Millions Like Us” and “A Canterbury Tale” also speak of the irrevocable political shifts that were part of the successful war effort.

It’s well known that, at the beginning of the Blitz, ARP was ill-prepared. The authorities were unwilling, nevertheless, to let ordinary people take refuge in the Underground. They feared that people would simply stay below for the duration! This lack of faith, on the part of the authorities, was never forgotten.

I agree with everything you’re saying there about how the myth of the blitz and the war more generally has been retrospectively put together and is in no way the whole story.

But what also intrigues me is why this myth is so potent right now, and so I would argue that, although Keep Calm and Carry On is a slight part of the story of World War Two, it is very significant now. (And the fact that its backstory is available in the books, but somehow never makes it into the popular histories of the poster is also of significance too).

Nowadays I think a slightly different myth of World War Two is being assembled, one which has particular resonances for the present day. Yes people did want to see parallels between the war and the financial crisis when Keep Calm was at the peak of its popularity. But more than that, we keep poking the war because it is a way of addressing our own anxieties about modern life and society – issues such as excessive consumption and inequality. I’ll try and do a proper post about this one of these days, as I think it might be worth unpacking the argument at a bit more length than I can do in a comment!

In a similar vein to the ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster…I was watching a short documentary made for the Ministry of Information in 1940 called London Can Take It the other night and noticed an enormous banner on one building in a London street saying, ‘ Carry On London and Keep Your Chin Up’! No idea who was responsible for it though. Probably a one off but it looked professional.

I think that has to be the next merchandising opportunity, don’t you.

Would be interesting to know who did it though. I would have thought it must have been quasi-official, otherwise how would they have got the materials to make it? Although it might have been possible that early in the war, perhaps.

Do you know who created the keep calm poster? I’ve tried to research it, and the closest I could come was possibly fhk Henrion. Is he the creator?

I don’t think it was Henrion. The short answer is that no one really knows – the posters were produced within the Ministry of Information before that officially existed, and I don’t know of any reference in the records to the artist. How have you come by the suggestion of Henrion? I’d love to know where that came from.

I think you will find that Vita Sackville-West was married to Harold Nicholson. Their son was Nigel, I just hate it when the facts are wrong.

You are absolutely right, that was au unthinking typo. Now changed, thank you for pointing it out.