You may need to bear with me on this post. I’ve been thinking about writing it for at least a year, possibly longer. I’m sure all the ideas made a lovely linear argument when I first had them, but I’ve pondered them so long that they’ve all turned into some kind of thought soup. The ingredients include bombs, posters and a very famous John Betjeman poem. Only writing will tell me if they still make sense together, so here goes.

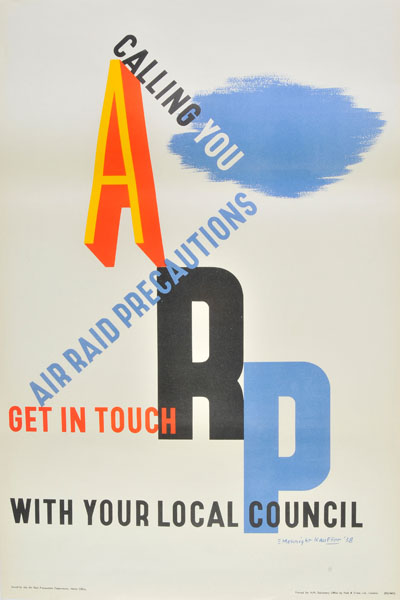

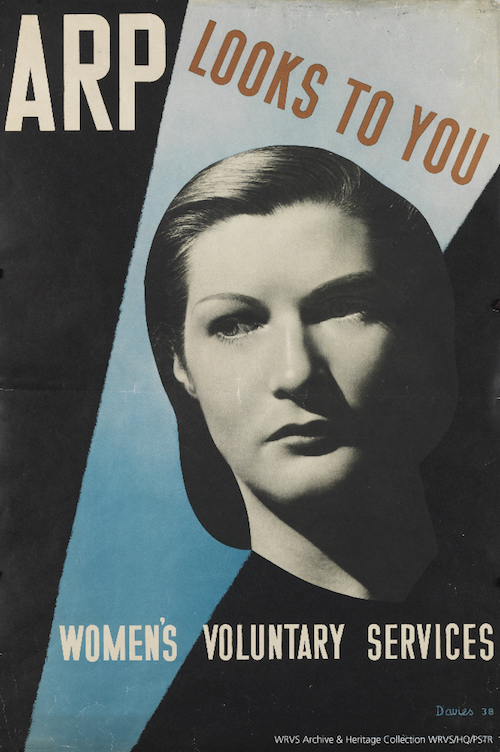

The easy part is the poster, which is this design by Edward McKnight Kauffer, commissioned by the Air Raid Precautions Department of the Home Office in 1938.

Every so often I come back and think about this poster, and not just because we’ve got a copy framed on our walls. I’m intrigued by what living through those years of the late 1930s must have been like, with people trying to live their normal lives as much as possible, but all the time knowing that war was looming dark and unavoidable in the very near future.

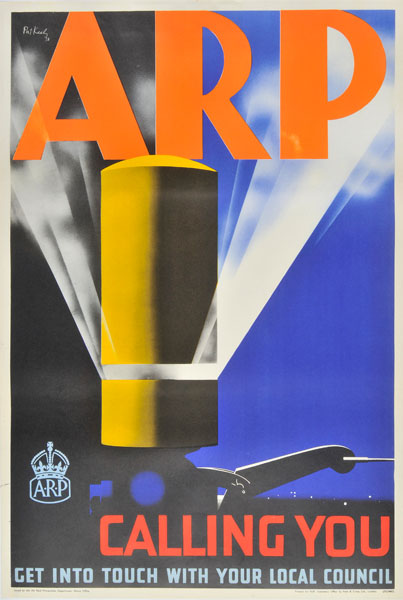

I’ve always thought that the allusiveness of the poster – you are invited to join ARP without any clue about what you might be joining or what the organisation might do – was because no one was very clear about what the war in the air might involve. Pat Keeley’s companion poster is similarly vague.

Perhaps it was the misunderstandings behind the Keep Calm and Carry On poster which led me to think that no one really foresaw the reality of bombing raids, but that’s certainly what I believed. The posters show nothing because back then no one really knew what was to come.

How wrong I was, it turns out. People, not just the army, not just the government, but ordinary people in the streets, newspaper readers and casual observers, knew exactly how the bombers would come when war was declared. It had been shown to them for years, and the evidence was actually there in plain view, if only I knew where to look.

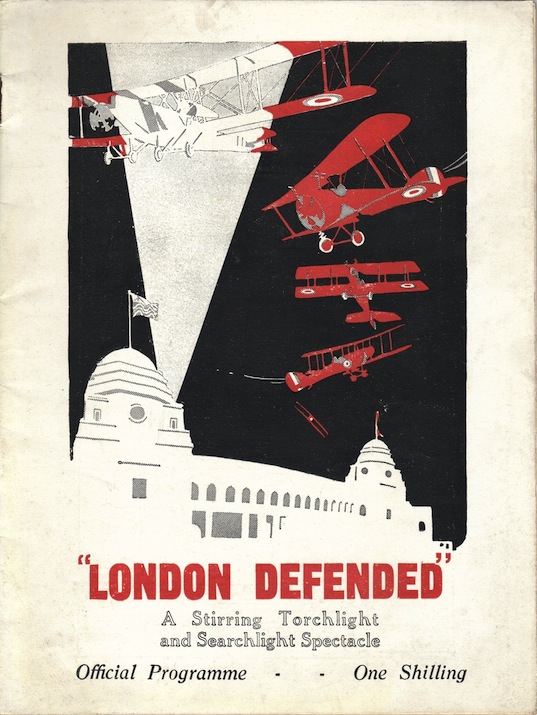

The first clue to this came in a history of the inter-war years, which I was reading for another reason altogether, but piqued my interest by mentioning ‘London’s Great Air Battle’ which was staged in 1925. Here’s the account from the News of the World, as reprinted in the book.

Powerful searchlights…stabbed into the path of darkness overhead, sweeping the skies for the menacing machines….Guns manned by alert teams rattled away as they spat out their imaginary stream of shells into the heavens and the invaders circled round and round loosing their cargoes of destruction from the heights.

Someone clearly had a very good idea of what the next war would do to London. But who? I nearly broke Google trying to find out (London’s Great Air Battle wasn’t actually what it was called, so this made life a bit more difficult than it might have been).

Until I eventually – and really this did take a couple of days – found a perfect blog. It’s called Airminded, and it’s subject is Airpower and British Society 1908-1941. I’d say that it couldn’t be more perfect, were it not for the fact that the author of the blog, Brett Holman, has also written a book called The Next War in the Air: Britain’s Fear of the Bomber, 1908-1941. Which is exactly what I needed to know. Except it’s an academic book, and so costs £75. But never mind, the blog gives us more than enough information to look at the posters in a new light.

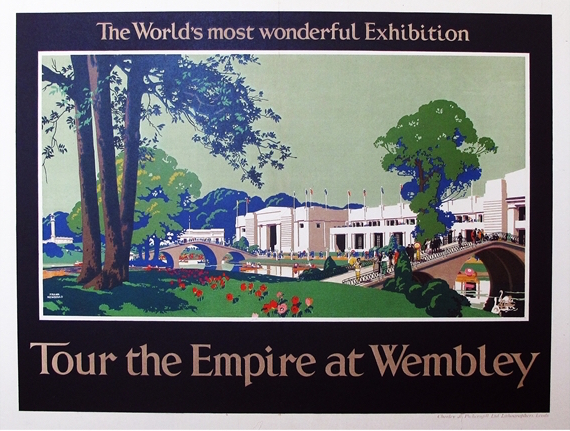

It turns out that these displays were put on as part of the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley in 1924 and 1925.

One of the many attractions was that No 32 Squadron of the RAF simulated the bombing of London in a thrilling display of pyrotechnics that included anti-aircraft guns and fire engines. And not just one display either, these ran six days a week for nearly a month.

As Holman points out, this was a lot of time, energy and aeroplane for the RAF to commit, so they must have been convinced that there was a propaganda purpose in all the spectacle. They wanted people to know that the RAF was the most modern and exciting of the fighting forces, they wanted people to understand that the next war would be fought in the air and so the RAF would be essential. But a side effect was that it made clear to people that, should the next war ever come, London would very definitely be in the firing line. (It’s also notable that the Air Raid Precautions Department that commissioned the posters was also founded in 1924, which given the propaganda nature of the displays may be rather less than coincidence).

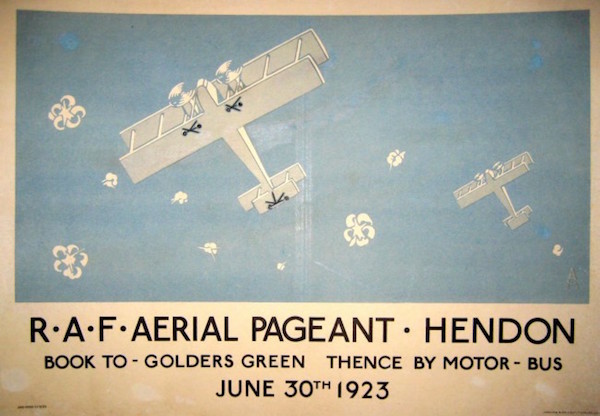

This wasn’t the only place that the RAF were showing their workings either. The RAF Aerial Pageants had been held in Hendon since 1920 – and it’s worth noting that a lot of lovely London Transport posters were produced to advertise them too (this image from Kiki Werth).

In 1926 and 1927, one of the high points of the spectacle was set piece displays of the bombing of London. The pageants, too, were large scale events – 150,00 people visited in 1926 alone. None of this was a secret.

However, back then in the twenties it wasn’t necessarily clear then that another war was imminent. So the shows could just be seen as hypothetical displays. Perhaps even the results of the Air Defence Exercises that ran alongside the Wembley and Hendon events were not as frightening as they seem now with hindsight. Each summer, starting in 1927, the RAF High Command tried to bomb London with some squadrons, while others tried to defend it. The results were clear each time, the bomber almost always got through. And this conclusion was widely reported in the newspapers when it happened year after year. By 1932, the results must have felt at least a bit ominous though.

As the decade turned and the 1930s rolled on, it must have been apparent to even the most casual observer that was would be very different next time round. No more trenches, no more stale mate. The new war belonged to bombers, and the bombs would not be falling on soldiers alone, everyone in Britain would have to be prepared for what might come.

The final piece of evidence for this is John Betjeman, and perhaps his most famous lines of all.

Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough!

It isn’t fit for humans now,

There isn’t grass to graze a cow.

Swarm over, Death!Come, bombs and blow to smithereens

Those air -conditioned, bright canteens,

Tinned fruit, tinned meat, tinned milk, tinned beans,

Tinned minds, tinned breath.

These lines aren’t the result, as somehow I’d always assumed, of hindsight, the poet summoning the bombs back in the 1950s to do their work again. Although Betjeman published the poem in 1937, he actually wrote it in 1928. This is ten years before those ARP posters, and yet there’s no explanation in the poem, no need for him to explain what the bombs will do. Everyone understands.

All of which means that when I now look at the posters again (this is a third one, produced for the WRVS but in 1938 as well) I have to see them in a very different way.

Their vagueness isn’t the result of evasion at all. On the contrary, everyone is so clear about what the next war will involve that the realities don’t need to be mentioned at all. No one wants to see the blasted corpses, the broken homes, the dead children. All that needs to be said are the three letters of ARP, and the viewer of the poster knows what has to be done. Because war is coming, and this time the war will come from the air and no one will be spared.

That is all very clear, cogently expressed and strips all the glamour off these ARP posters, leaving them more than a bit chilling. Particularly that last one. Brrrrrrr.

Cogent, well-argued, fascinating. Thank you for posting.

It’s always amazing when our curiosity about a favourite thing leads to these trips into exploratory country. That’s why I like blogging. I’m thrilled when there are follow ups to things I write in all innocence thinking I’m talking to the wind.

Anyway your article was really interesting. I can’t see the appeal of the initial poster myself (pleb that I am) but understand how it set you off on a trek! And how interesting that despite the massive destruction of WW1 we were prepared to put on such a show to the public. I can’t imagine that happening after WW2 but we did get the Festival of Britain…much nicer! Thanks

Thank you everyone.

And yes, it’s an interesting point you make about the reactions to the two wars. ‘The War to End All Wars’ gets Hendon and the Empire Exhibition, not the Festival of Britain…

As ever, a thoughtful and engaging piece – and I ‘ve seen very few of these images before.

Last year, I became aware of the German “Blackout” poster campaign. It wasn’t quite so austere as McKnight Kauffer’s work.

Image here: https://www.dhm.de/fileadmin/medien/lemo/images/pl004404.jpg

PS I hope you received my email about Hans Unger.

Neil

What’s the date on that German poster, do you know? It’s interesting because it very much lines up with what John Gloag was saying about German propaganda in about 1940. And yes, I did get your email, have been v busy but will a) answer and b) post as soon as I can.

Hi, a copy was sold last year that seemed to have a lot of helpful information in the listing, but I’m afraid I didn’t make a note. Getty Images, places it around 1943, which makes sense if you accept that the gruesomness of the image is as much a reaction to previous horrors as much as a warning. My history is shaky here, but I think the UK didn’t pursue a civilian bombing policy until 1942 into 1943 (Hamburg etc). Fascinating that the Germans had a similar campaign to us, it’s almost like we were all human beings or something….All best, N

Fascinating and thoughtful once again, thank you. Could I persuade you to give a talk to the Art Workers’ Guild the year after next?

It occurred to me yesterday, looking at the images on the Spitalfields Life website (http://spitalfieldslife.com/2015/10/02/scars-of-war/), that many people would be aware of the potential of bombing in WWII as a result of the Zeppelin bombing in WWI.

Neil, that’s interesting. I suppose I ought to look at the evolution of blitz posters after the bombs had started dropping. But the UK had a very definite anti-shock policy as far as posters were concerned, so would never have produced anything like that.

And yes, the Zeppelin raids must have had an influence – I will read Brett Holman’s PhD thesis (which is, he tells me, online and free) and let you know about that one in a bit.

Finally, my 2016 diary is currently entirely clear, so I wouldn’t need too much persuasion…

Fantastic, thank you! I’m putting together the programme for 2017, not next year, so plenty of time…

Funnily enough, my 2017 diary is also entirely clear too, so plan away.

I suggest that the Zeppelin raids were never more than a minor nuisance, and by 1917 had been controlled, if not defeated, by the defence. The WW1 bombing campaign with the greatest impact was the Gotha aircraft raids of 1917/18. [The 7/7/1917 raid mentioned on the Spitalfields site above was by Gothas, not by Zeppelins.] The Japanese bombing of undefended Chinese cities in the 1930s probably had a limited impact in Europe because of minimal interest by the media, but the results of the bombing of Guernica in Spain 26/4/1937 were extensively publicised, and probably did the most to increase public and governmental perception of the risks.

I completely agree with you that Guernica must have been a turning point, but the awareness existed even before this, as the Betjeman poem shows. I will read some more and come back with answers!