Today, dancing about architecture. Or at least its close relative, podcasting about posters.

Actually, I’m being a bit unfair here. What I’ve been listening to is historian Scott Anthony on the BPMA podcast about Stephen Tallents, the man who brought artists to the GPO poster and Night Mail to the nation. Although the lecture did still have slides, and yes, I couldn’t see them.

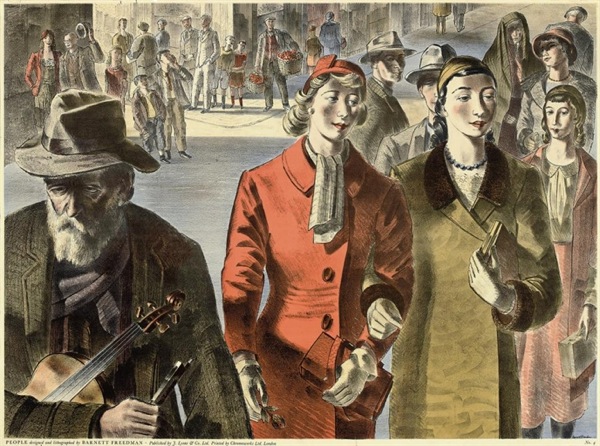

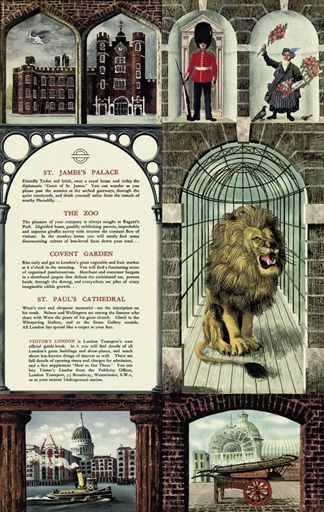

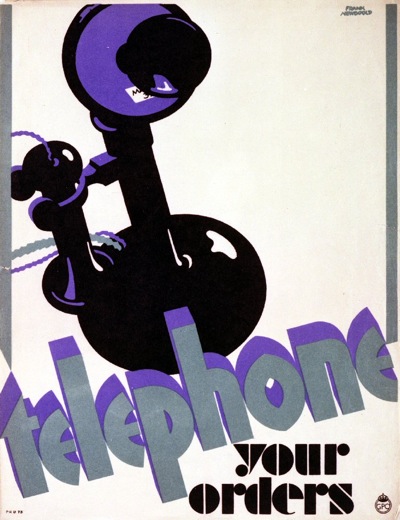

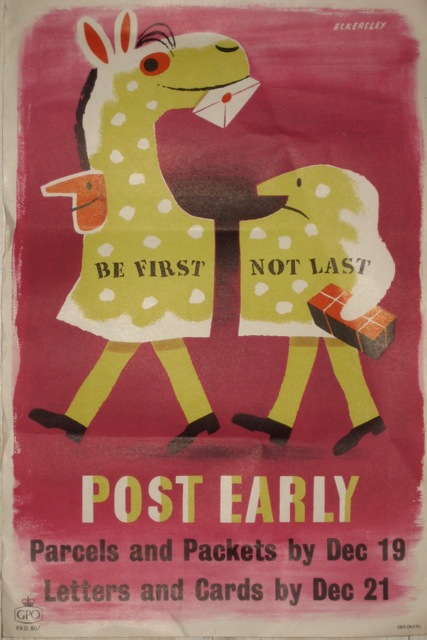

poster by Barnett Freedman commissioned under Tallent’s watch at the GPO

Nonetheless, this was a useful listen, not least as a reminder of just how huge and influential the GPO was in the inter-war years. The largest employer in Britain, with over quarter of a million employees, it had a monopoly of communications which is almost unimaginable today, including oversight of the BBC. So Tallents, as their head of public relations, had enormous influence to wield and a huge audience for his efforts.

McKnight Kauffer Airmail Routes for GPO 1935

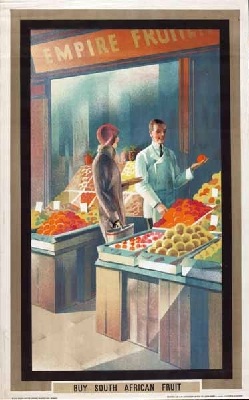

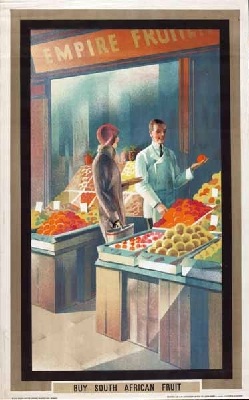

What fascinates me most is how much the great poster art of the pre and post war periods depended on the individual patronage of a few idiosyncratic individuals. This does not only mean Tallents – who first started using talented designers when he was at the Empire Marketing Board before joining the GPO.

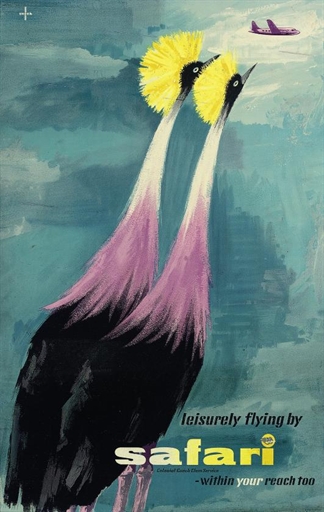

Austin Cooper for Empire Marketing Board, 1933

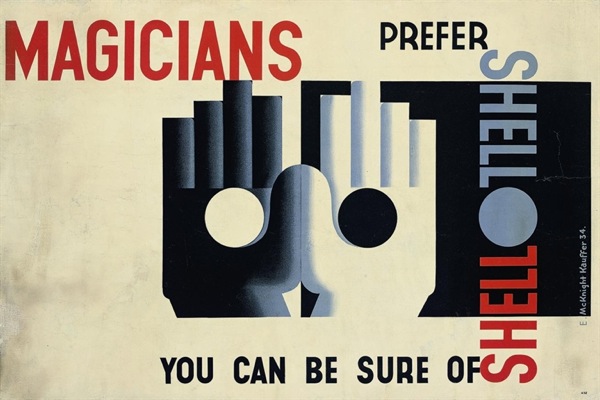

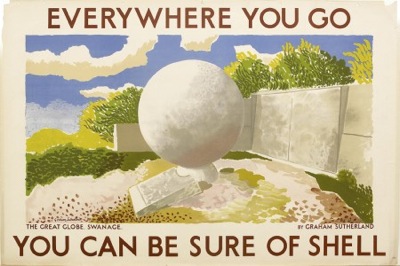

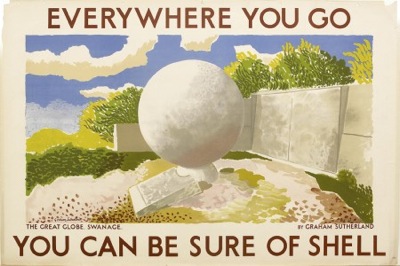

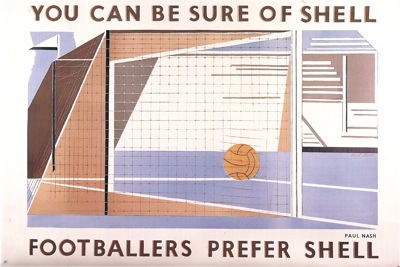

Also following a remarkably similar track were characters such as Jack Beddington at Shell,

Graham Sutherland, Swanage for Shell

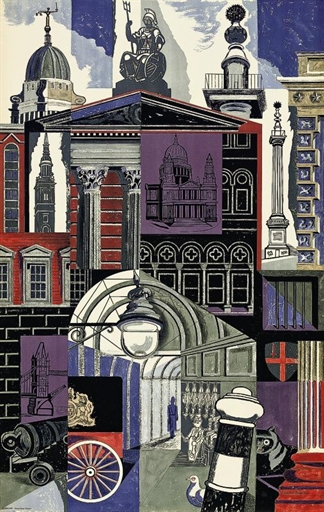

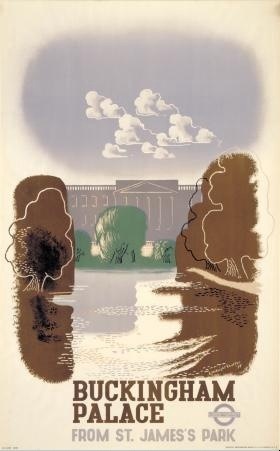

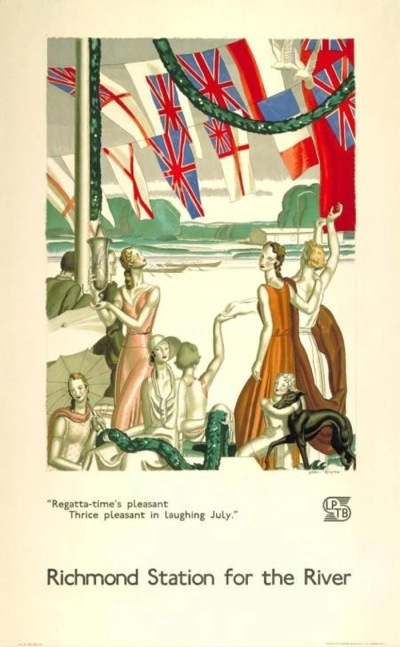

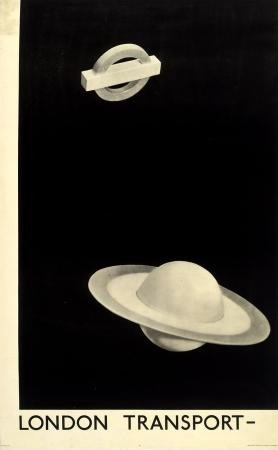

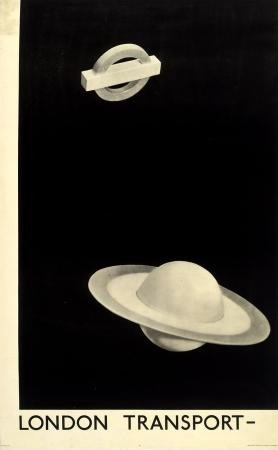

and of course Frank Pick at London Transport.

So why did they do it? It’s a question that I think is important, because their attitude lingered on well after the individuals themselves had left their jobs. Major companies and institutions employed great designers and artists to produce their publicity right up until the 1960s, simply because by then it was the done thing. So how, and why did it start?

Anthony believes that this is mostly the corporate expression of the age-old notion of patronage. Great designers and artists were employed because that’s what important people have always done; it’s just that, after the First World War, the important people happened to be companies and public institutions rather than dukes and kings. There is some truth in that. Nikolaus Pevsner said of Frank Pick that he was the “Lorenzo the Magnificent of our age”.

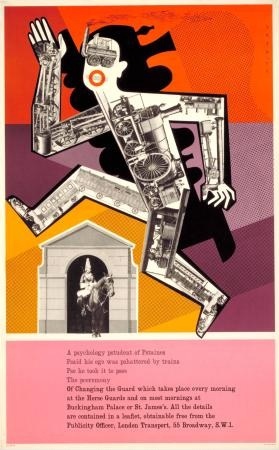

Man Ray for London Transport

It’s almost possible to justify this as a logical business decision: great artists = great corporate image, which is how Anthony sees it. But I also think that there is more to it than that. In particular, there is a very particular belief in this period, associated with British modernism-lite, that design can be Good For You. The lower orders will be morally improved, or at very least will stop liking chintz and veneers and pictures of kittens, if we just expose them to what great art and design is. In its later incarnations, it brings us Utility furniture (the nation’s taste will be improved by good design because we won’t let them buy anything else) and tower blocks, which will make them happy people via the medium of modernist architecture. But before the war, its main expression was in the commissioning of posters.

Both Jack Beddington and Frank Pick were trying to create art galleries which, while making Shell and London Transport look like forward thinking and enlightened companies, would also enrich the cultural lives of the people who saw them.

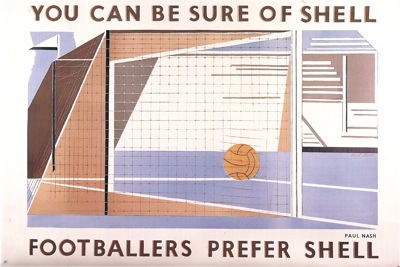

Paul Nash for Shell

And as a result they both – unlike for example the railway companies – tended to commission artists at least as much as designers. Shell used Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Duncan Grant and Ben Nicholson. While London Transport commissioned Man Ray as well as McKnight Kauffer. Even Stephen Tallents commissioned Vanessa Bell to produce a poster for the GPO (although it was never used)

Shell explicity referrred to their lorries which carried their posters on the sides as a travelling gallery, and as John Hewitt notes, they are displayed in a ‘frame’ of white space, with the text not allowed to encroach on the image, allowing viewers to see the design as an artwork as well as advertising.

Shell lorry with billboard, 1925

For London Transport, Pick was even more explicit. In 1935 he described the whole of London Transport as a work of modernist art.

…underneath all the commercial activities of the Board, underneath all its engineering and operation, there is the revelation and realisation of something which is in the nature of a work of art…It is in fact a conception of a metropolis as a centre of life, of civilisation, more intense, more eager, more vitalising than has ever so far obtained.

And how better to express that than in the modernist forms of McKnight Kauffer, for example?

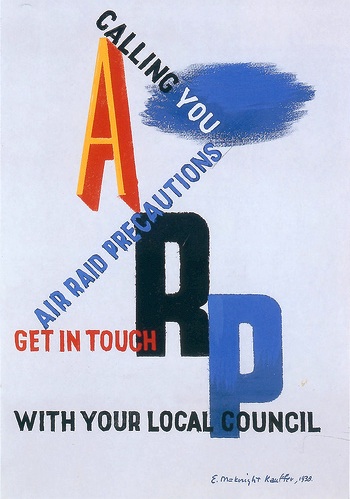

Even the GPO was not immune. Anthony pointed out in the podcast that there was a Poster Advisory Group, set up by Tallents, which was there to ensure that the artworks were only of the highest quality. Its members were Kenneth Clark, art historian and general arbiter of taste, the art critic Clive Bell and Shell’s Jack Beddington (Kenneth Clark opened exhibitions of Shell posters for Beddington; the world of good taste was a small one). Now, this for me is a real give away about the purposes of these posters. This committee isn’t a group of people who are going to have an opinion about the commercial effectiveness of posters, they are simply there to make sure that they conforms to the highest possible standards of prevailing artistic merit. The GPO, being such a huge national institution, has a moral duty to improve the quality of Britain, and Kenneth Clark and co are going to make sure that they stick to the task. (I’d quite like, incidentally, to read the minutes of this august body. Perhaps I’ll turn into a historian and do that one day).

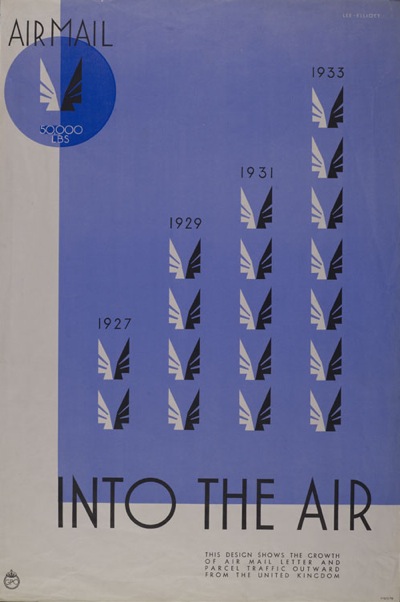

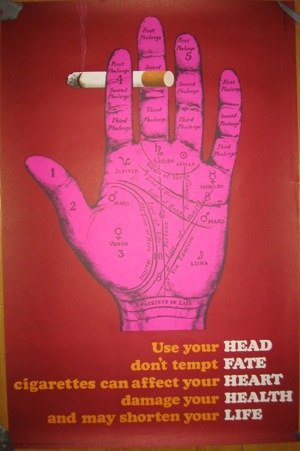

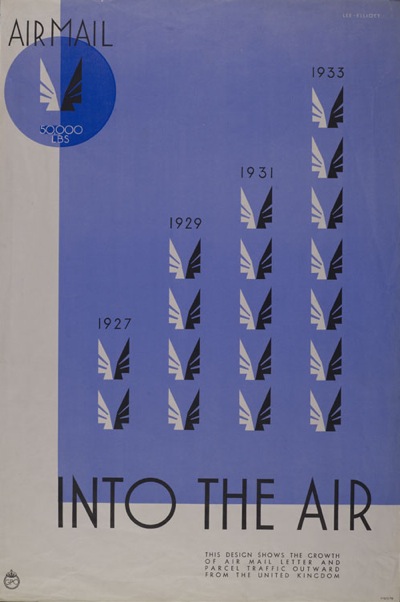

(This, by Theyre Lee Elliott was the first design they approved in 1935).

But now those attitudes have almost completely disappeared. We are too cynical to believe that good design, or indeed anything done by a corporation, can improve us. The only national institution which has a vestige of these attitudes remaining, is the BBC, which we still believe should do us good rather than make a profit. Whenever people talk about the BBC, though, these attitudes are always described, somewhat disparagingly, as Reithian. I think that’s a bit unfair on poor old Lord Reith. What Scott Anthony and all these posters have shown us is that the idea that great national institutions should improve our lives in some way, was all around between the wars. It’s just that Lord Reith’s ideas of how this should be done are pretty much the only ones which remain.

As if to demonstrate how much the ideas of what institutions should do for us have changed, an ad for the Post Office came up on Spotify while I was writing this. Twice. They’re giving away iTunes gift cards to coincide with stamps of great album covers. But the end line of the advertisement is “Win enough free music to annoy loads more people”. Need I say any more.

The next BPMA podcast, meanwhile, is Paul Rennie, talking about GPO posters. As someone who relishes a challenge, I’m rather looking forward to it.