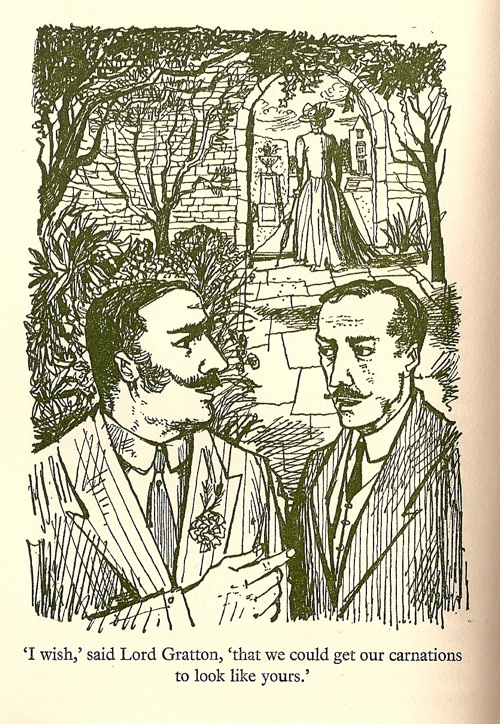

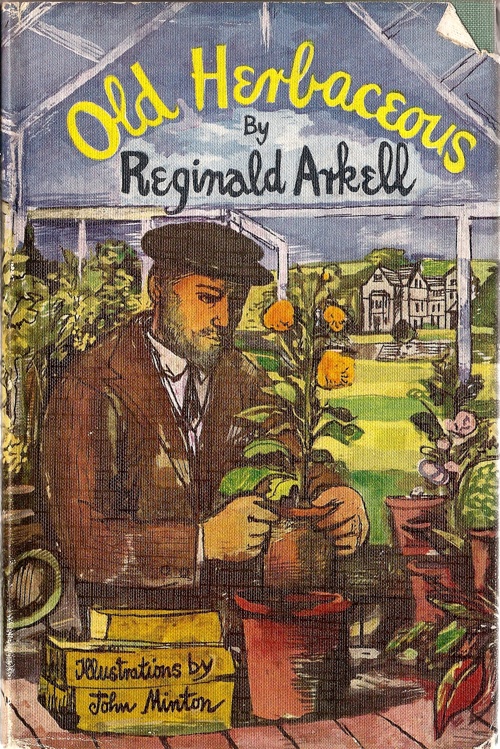

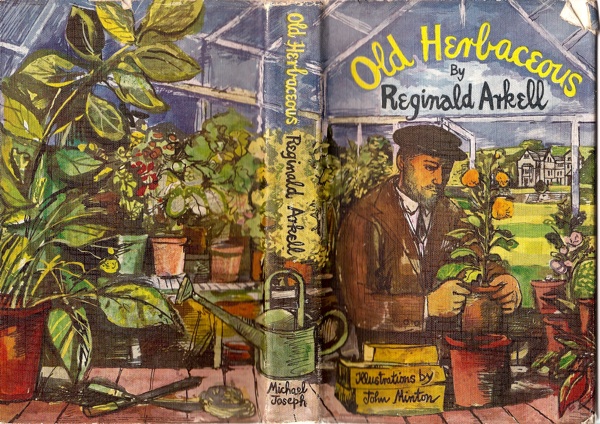

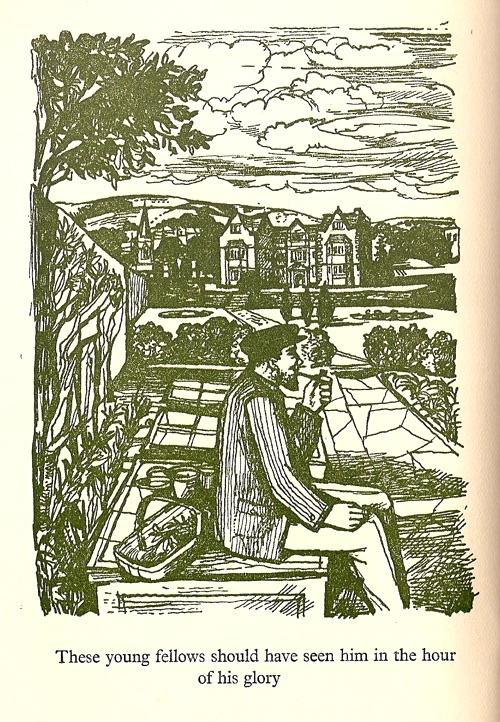

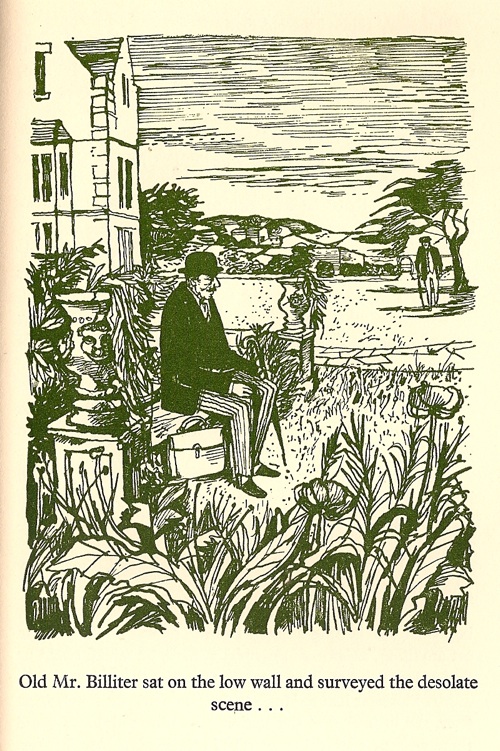

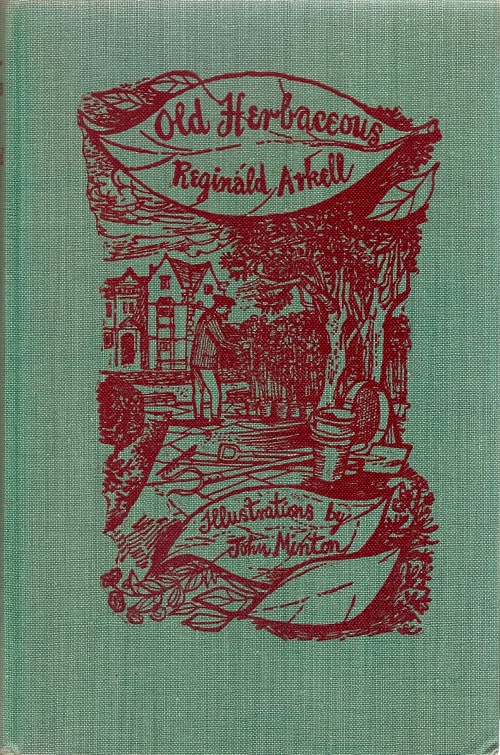

As it’s not only Valentines Day but sunny, some flowers. With accompanying gardener, both by John Minton.

I got this for the grand sum of £5 at the weekend. An antique shop in our town has now started selling second-hand books; there is an open wood fire and a wing-back armchair to one side in which to consider. It’s perfect. And the books are underpriced too, so I really can’t fault it.

But there’s more to this book than a bargain. It’s also a thought about the world after the war.

Over the last few months on the blog, I’ve been wondering out loud about the tensions between modernism and another current in British graphics and posters – an urge towards tradition, the rural, a sense of Britishness rather than pan-national design styles (here and here, for example if you want to go explore this in more detail). Alexandra Harris calls it British Romanticism, and the proper expression of it is entirely her idea.

All of which begs the question, well what happened after the war? Did this survive, or was it washed away by the urge to build a bright new world out of primary colours and light wood in the style of the Festival of Britain? A modern world, cleared at last of clutter and romantic nostalgia? I don’t know the answer to this question, and so for a while now I’ve been meaning to take a slice through a year, perhaps 1949 or 1950, and see what can be worked out from the works I turn up.

I’ll still do that one day but now instead, in the way of all coincidences, I have this book, published in 1950. And there’s no brave new world here. Rather, it’s hard to find an illustration which doesn’t speak of nostalgia for a time and a social order which has now passed.

This mood is whole raison d’etre of the book itself, as it’s the (fictional) memories of an old gardener. Nostalgia, class and the rural all bound up in one story.

It’s the natural successor to Recording Britain, because once the old world has been destroyed, it can only be recreated in fiction. And illustration of course.

He could have illustrated the book in a more modern style but Minton has also chosen to make other references to the past, like these delightful chapter numbers, each one hand drawn, which look forward to the Regency references of the early 1950s. Modern, it is not.

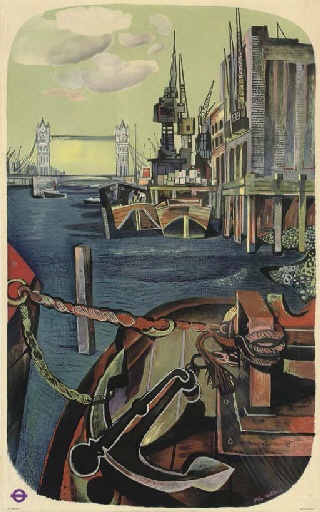

Now this is one book, illustrated by one man, but this mood runs through a lot of Minton’s work. His Thames for London Transport is, at best, timeless – and also clearly the heir of the romanticism of Sutherland and Piper, made slightly more friendly for a commuting audience.

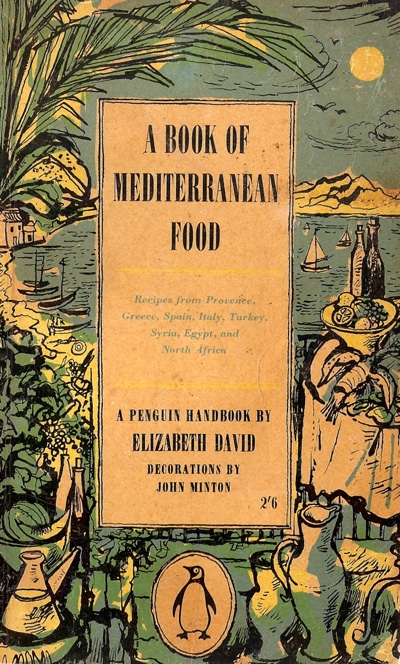

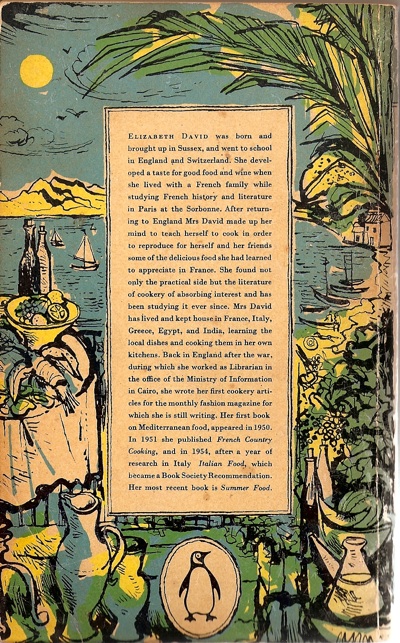

While perhaps his most famous illustrations – for Elizabeth David’s Mediterranean Food, published in 1950, the same year as Old Herbacecous, are also exercises in if not actually nostalgia then certainly escapism (excuse the state of it, this is my working copy and was clearly someone else’s before that).

Because this book isn’t a Jamie Oliver manual on how to cook better, it’s an exercise in conjouring up a world of sunshine and pleasure that was almost completely inaccessible in Britain in 1950. Food was still dull and rationed, olive oil was medicinal and currency restrictions ensured that only the very richest of all could think about travelling to the Continent. Mediterranean Food was written not as a set of instructions (as anyone who has tried to cook from it can testify: “Take a silver bowl” – but where from, Elizabeth, where from?) rather as an act of rebellion.

Hardly knowing what I was doing […] I sat down and started to work out an agonised craving for the sun and furious revolt against that terrible, cheerless, heartless food by writing down descriptions of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cooking. Even to write words like spices, olives and butter, rice and lemons, oil and almonds, produced assuagement. Later I came to realise that in the England of 1947 these were dirty words that I was putting down.

It’s all to easy to believe that the post-war world sprang into life fully formed at the Festival of Britain, sprightly and cheerful on its spindly metal legs. But to start with, that leaves out six whole years. Six years which seemed to those living through them to be grim, colourless and dreary, a time of hardships without any of the frisson and purpose of the war. As the country desperately tried to pay for the victory, there were no bright colours or new products in the shop, everything that could went for export. In this world of suet, cabbages and perpetual rationing, it’s hardly surprising that escapism of one kind or another was popular. A popular modernism had to wait until a bit later, when the bright new future at last seemed to be within reach.

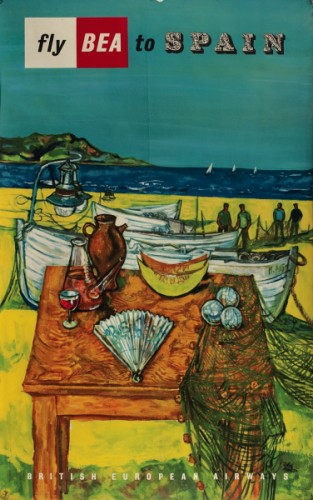

This world of yearning does seem to have been Minton’s natural territory in his illustrations – here he is in 1950 again, producing the same vision for BEA, although this time for the few who could afford it.

It’s both a still life and a vision of an almost unattainably different place. (This poster is available from Sotherans at a surprisingly reasonable £295 if you are interested. I almost am).

Two small asides. This is halfway between a look at Minton and an essay, and probably not quite managing to be either properly. Lest you think I’m reading too much into one man’s work, there’s also David Gentleman and Roger Nicholson, producing the same kind of nostalgia for a lost world of food at almost exactly the same time, in a style which, then, owes very little to International Modernism.

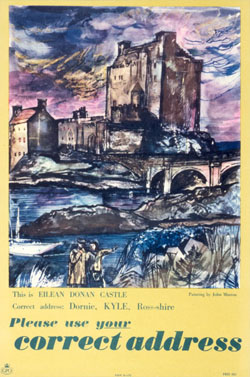

And if you’d like to know a bit more about Minton’s poster work, Martin Steenson at Books & Things has written an overview of exactly that. To which I am able to add this GPO poster from 1957.

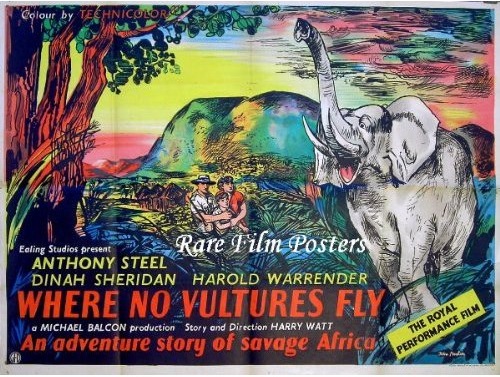

And this film poster too.

Bizarrely, this is for sale on Amazon (are there other posters out there? must find out) and for £850. Which is too much anyway, but especially for something which would give me a headache within ten minutes of sharing a room with it. Let’s end with something more restful, shall we.

After all, there’s always a place for escapism on Quad Royal. Especially on Valentine’s Day.

It’s interesting how much more together the design is when it has Minton’s hand-lettering, rather than a block of type dropped in

I find the tensions between modernism and ‘Britishness’ fascinating and one I return to frequently. I love where your thoughts are going in this piece…

Thank you both. And yes, I agree re the Penguin book. Minton did do a more illustrative cover, I think for the hardback, but I don’t have it (and wouldn’t dare use it for cooking from I suspect).