Bossiness, it seems, is all a matter of context. After musing on bossy World War Two posters the other week, I’ve been doing some more digging, and found John Gloag considering the subject of propaganda as it was happening in 1941.

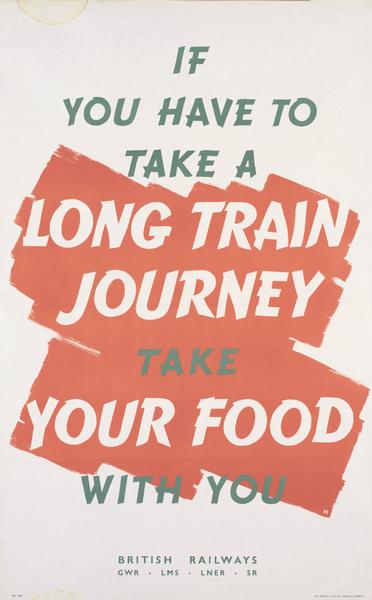

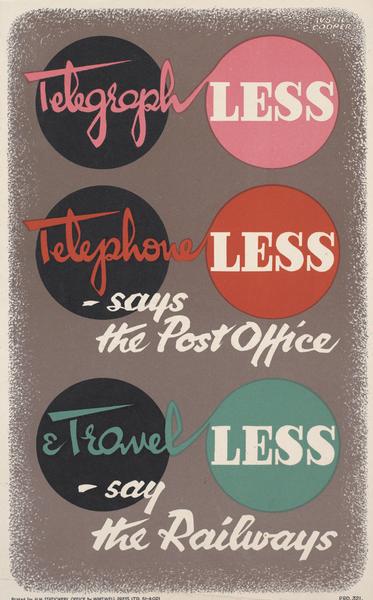

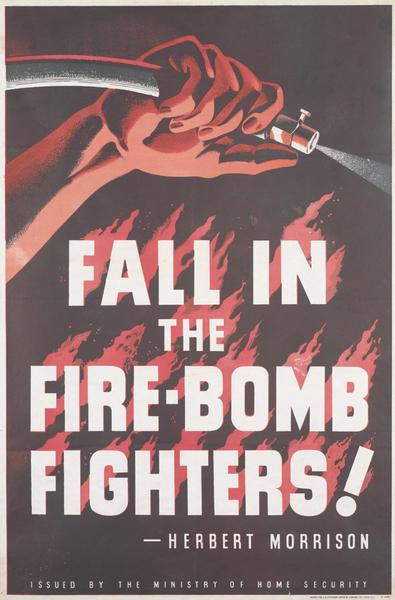

Now, I find posters like these (once more from the Imperial War Museum, via VADS) at the very least, a bit abrupt.

But to Gloag, they are the very epitome of restraint.

Unlike the admonitions, threats, boasts and hysterical appeals that foam and froth from totalitarian propaganda departments, offical propaganda for home consumption in Britain has been sober, restrained and well-planned. […] There have been suggestions, not bleak instructions, often conveyed with real human understanding.

Now I don’t think Gloag is necessarily wrong – he also makes some very good points in the same essay about humour being the secret weapon of British Propaganda which I think are definitely true. What interests me is the gap between how he sees the propaganda of the time, and how we perceive it now.

Sixty years on, we have a very different attitude to authority, and we don’t much like our posters giving us orders, however understated they are about it. Although I am sure that the note of this one would have wound me up even under the conditions of total war.

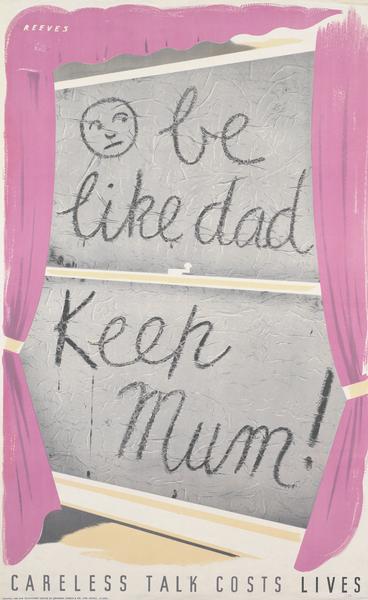

There are suggestions, too, that I wouldn’t have been alone in my resentment. This slogan – used on a range of posters – caused an exchange in Parliament that seems strangely contemporary.

Dr. Edith Summerskill asked the Minister of Information whether he is aware that the poster bearing the words “Be like Dad, Keep Mum,” is offensive to women, and is a source of irritation to housewives, whose work in the home if paid for at current rates would make a substantial addition to the family income; and whether he will have this poster with drawn from the hoardings?

Mr. Cooper I am indeed sorry if words that were intended to amuse should have succeeded in irritating. I cannot, however, believe the irritation is very profound or widely spread.

Dr. Summerskill Is the right hon. Gentleman aware that this poster is not amusing but is in the worst Victorian music-hall taste and is a reflection on his whole Department?

Mr. Cooper I always thought that Victorian music-halls were then at their best.

Dr. Summerskill Is the right hon. Gentleman aware that if he goes to modern music-halls, he will find that this kind of joke is not indulged in and that this suggests that he is a little out of date for the work he is doing?

There are also signs of a more general resentment. One Mass Observation reporter wrote in 1941,

Taking a short walk from the office where this report is being written, you will see forty-eight official posters as you go, on hoardings, shelters, buildings, including ones telling you:

to eat National Wholemeal Bread

not to waste food

to keep your children in the country

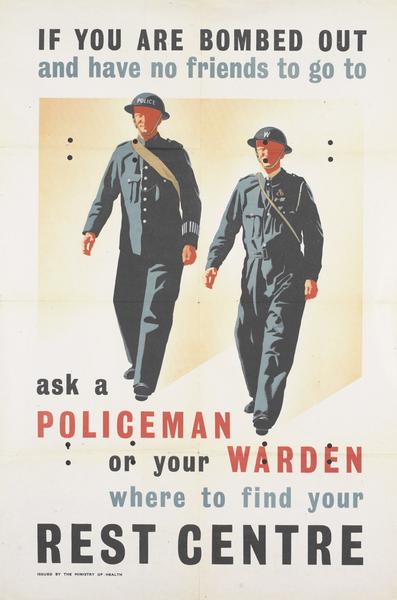

to know where your Rest Centre is

how to behave in an air raid shelter

to look out in the blackout

to look out for poison gas

to carry your gas mask always

to join the AFS

to fall in with the fire bomb fighters

to register for Civil Defense duties

to help build a plane

to recruit for the Air Training Corps

to Save for Victory.

It’s hard not to hear a note of brow-beaten exasperation in there. Probably intensified by the fact that, while we tend to see only the most memorable and best designed posters of the time, the vast majority of that list wouldn’t have been much to look at.

So was Gloag right or not? I don’t really know. He was writing in the middle of the war, so his essay was itself a piece of propaganda, keen to show the differences between the propaganda of the totalitarian regimes, and the gentle, herbivore suggestions of good old democratic Britain. And I think he’s keen to protest so loudly, partly because there is an underlying fear that this total war, which requires conscription, directed labour and mountains of propaganda, might seem to be turning Britain into a less gentle and more authoritarian place.

But how would we react to Gloag’s suggestions now? Or get the British public to mobilise in this way? Now that I really don’t know.

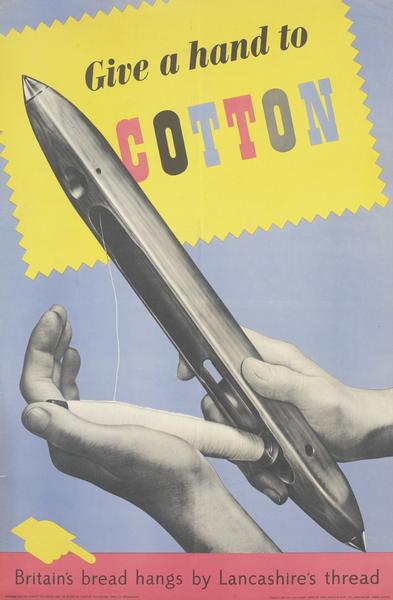

Finally, I have no idea at all what this poster wants me to do, but I do like the design.

Next week, more auctions I think.

I think I might adopt a strident tone if I were trying to motivate a nation through posters! But the ‘mum’ one is particularly bad.

The final cotton poster / message probably makes reference to the importance of the Lancashire cotton exports to the nations coffers. And thence the provision of bread – which remained unrationed for longer than most foodstuffs, I think.

Now scarily, as I have been reading a book about Austerity (lots of tables of figures, good late night stuff) I can tell you all about bread rationing. And you’re right, bread wasn’t ever rationed during the war (although white bread was verboten) as the theory behind the food ration system was that people could get enough calories from bread, potatoes (also not rationed) and going to National Restaurants. But after the war – when things were actually more difficult and ration amounts went down, it was rationed for a while (1946-48).

And I’m sure you’re right about the poster too; but I’m still very bemused about what it wants me to do. Eat less bread? Learn cotton weaving? Bake some eccles cakes in solidarity?

The extraordinary change and emphasis in use of language over less than a century fascinates me. The directness of these “messages” as propoganda or in commercial advertising belong to and reflect a different time, different set of values and circumstances, in effect I suppose they are historical statements telling the recipient what to do. I would be interested to know if there were any adverse reactions from the public to these kind of posters at time of publishing – I suspect few if any. Cultural and legislative changes have put us in a different place, full of sublety and nuance, we are now “advised “or given “suggestions” to think about things – which are intended to influence us into action. I wonder what will be said of the “sophisticated” messages in the various governmental and advertising media that bombard us these days in a century or so?

I think you’re right about all of that. There has been an enormous shift in the culture, specifically our attitudes to authority. So that now they only dare offer ‘suggestions’.

But I think that something else has changed, something that I can only really describe as the register of language. No one would construct these sentences any more, and I’m probably not alone in hearing them spoken in the clipped RP of a wartime film.

The question of reactions to posters is one which fascinates me too, and I’m still digging around trying to find the answers (or to be precise, trying to find a way of knowing this without having to make the trek to the Mass Observation Archive in Brighton!). There were definitely a few posters which were felt to be irritating at the time – but equally some, like the Fougasse ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ cartoons, were celebrated even as they were published. And the posters were probably more irritating once the war was over and the sense of necessity was past – the opening page of 1984 is one expression of this.

I love this post. What an insight into a nation at war, the info seems abrupt by today’s standards, but gets the message across. Thanks for sharing

Thank you for the kind words. Every so often I look at these kinds of poster and wonder how useful my generation would be in the event of total war and this kind of austerity.

The ‘Lancashire Thread’ poster refers, I think, to the post-WW2 Board of Trade recruitment drive to get workers back into the mills, and cotton industry in general when it was suffering from a severe labour shortage. There’s a fascinating film – whose title currently escapes me, that was issued as part of this campaign. It was, in retrospect, the last ‘fling’ of the industry that was primed to spearhead the late 1940s export drive when it was on the cusp of its terminal decline.

Ah, that makes sense. A Lancashire poster for Lancashire people, then. Thank you!