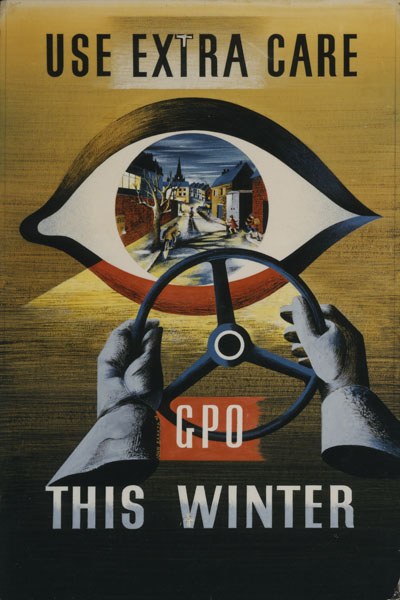

I’ve been meaning for a while now to dig out some old blog posts from the archives. This isn’t just to do with the current constraints on my time, but also because I’ve found myself wandering through the Quad Royal archives in search of this and that, and coming across things that perhaps could do with another chance to be seen. But in this case I have found myself so surprised that I really did have to repost it. In search of my endless promises to find out more about Kraber (represented here by a GPO poster) I came across this, which not only do I not remember writing, but which contains thoughts I don’t even remember thinking. Although perhaps your memories are better than mine.

See my urgent book.

I have had to read it very quickly, because tomorrow it goes back to the British Library for someone else to read urgently too.

Now its subject – modernism, bombsites and English culture – might not seem immediately applicable to our concerns here on Quad Royal. But in fact it’s been surprisingly enlightening, mainly because it has forced me to think about British Surrealism. Now this is a style which in the 1930s spreads very quickly from fine art into the world of graphic design.

But then, during the Second World War, it goes underground (a fine place for the art of the subconscious to be) and is seen no more. According to this book (Reading the Ruins if you want to buy it yourself rather than be hectored by the British Library) Herbert Read asked in 1951 what had happenned to surrealism?

The break-up of the Surrealist Movement as a direct consequence of the Second World War is an historical event which has never been adequately explained…

The book’s answer to this question is a very interesting one, which is that war itself was so surreal that it rendered the artworks redundant. This was Stephen Spender’s view too, in 1945.

The immense resources of all the governments of the world are now being devoted to producing surrealist effects. Surrealism has ceased to be fantasy, its ‘objects’ hurtle round our heads, its operations cause the strangest conjunctions of phenomena in the most unexpected of places,

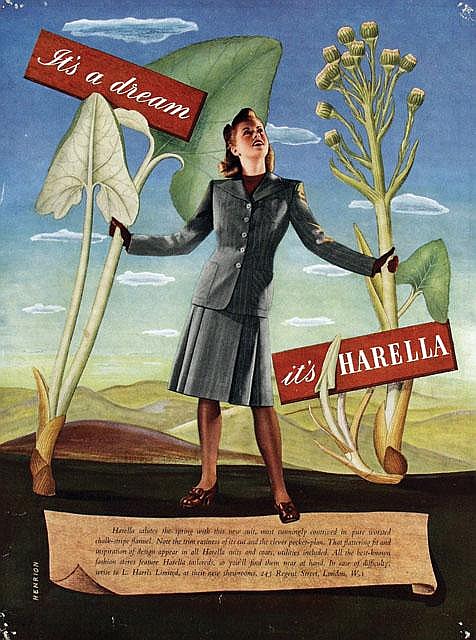

That’s an idea I’ll come back to in a moment, but what surprised me most about this was the idea that surrealism had disappeared. Because in graphic design that definitely wasn’t the case. We bought this quite recently – it’s by Henrion and I think dates from 1947.

His ‘Agriculture and Country’ pavilion at the Festival of Britain was also described at the time as surreal, with a giant white oak tree growing up through the space, while large swathes of Britain Can Make It also featured the same kind of odd juxtapositions of scale, space and objects too.

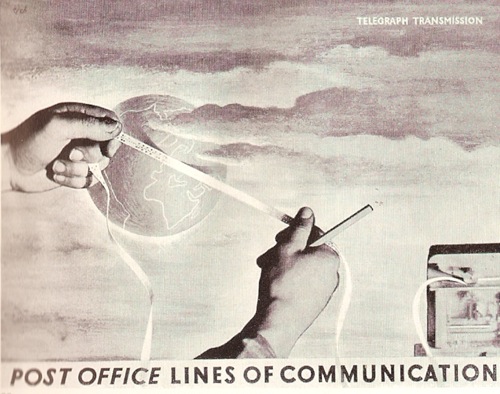

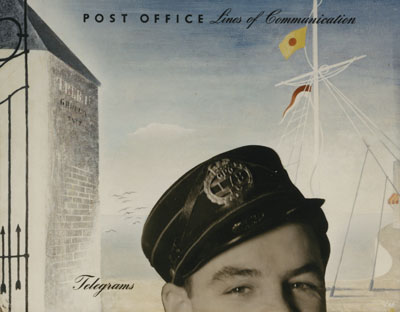

And remember those Lines of Communication GPO posters I mentioned a while back? There’s a strong streak of surrealism to be found in some of those as well.

And I am sure there is more elsewhere, too.

But thinking about World War Two posters (something I’ve been forced to do quite a bit recently), the surrealism is simply not there. Just as in the art world, it disappears; but the difference – compared to fine art – is that the style does come back after 1945.

Stephen Spender pins down very clearly the reasons why surrealism disappears during the war. Humankind can only bear so much strangeness, and the every day world offered more than enough during World War Two. Here is novelist Inez Holden remembering an episode during the Blitz.

One morning I walked back through the park, and saw the highest branches of a tree draped with marabout, with some sort of silk, with two or three odd stockings [and] … balanced on a twig was a brand new bowler hat. They had all been blown across the street from the bombed hotel opposite. A Surrealist painter who I knew slightly was staring at this, too. He said: ‘Of course we were painting this kind of thing years ago, but it has taken some time to get here.’

How this operates visually can be seen in the career of the photographer Lee Miller. Before the war, she had been a surrealist photographer. During the war, she is also a surrealist photographer, but this time it is called reportage.

(source Telegraph/Lee Miller archives)

The world is inside out and the surrealism of the subconscious is now on the surface. There is no need to invent it any more (If you want to see more of Lee Miller’s photographs, there is a good website of her works here).

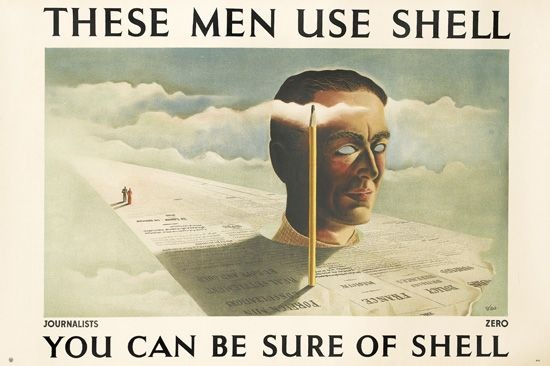

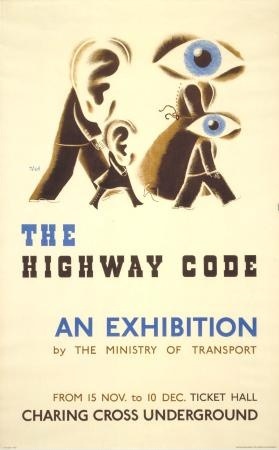

There are other, more pressing reasons for turning away from surrealism too. The disembodied hands – or in the case of this 1937 poster by Schleger eyes and ears – are now too disturbing to portray.

Because they are now not the fantasies of the imagination but the kind of body part that you might be unlucky enough to find on an ordinary street after a bombing raid.

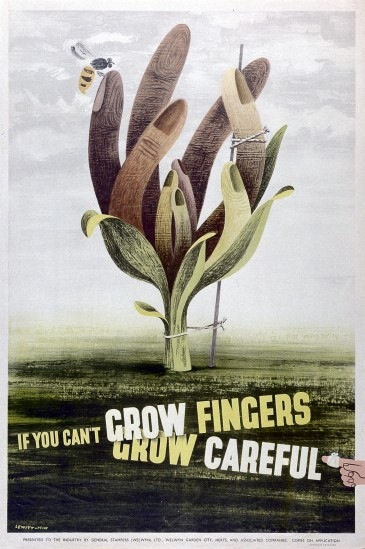

Interestingly, pretty much the only surrealist wartime poster I can think of – this safety one by Lewitt Him – is in part relying on this horror to make its point.

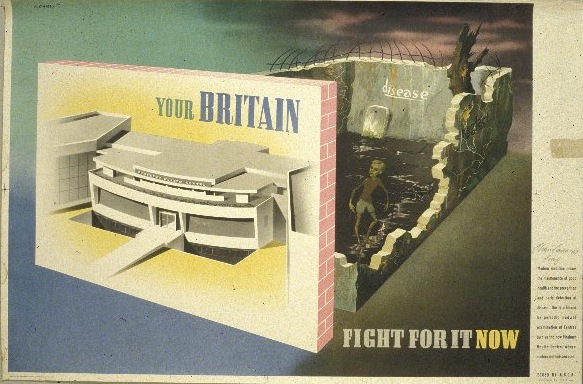

But this is a rare exception; the style of the war is modernism, not surrealism. And this is not only from a fear of the bombed out body. I don’t believe that people wanted to look into their subconscious during the war, there was too much fear and horror in there to be acknowledged. The black thoughts of death, fate and atrocity had to be banished into the underworld for daily life to go on. Instead it is the brighter future promised by modernism which helped them to get through.

Interestingly the Games poster above does have a surrealist element to it, but it is safely contained in a narrative structure; the black underworld is in the past, the bright modernism is in the future.

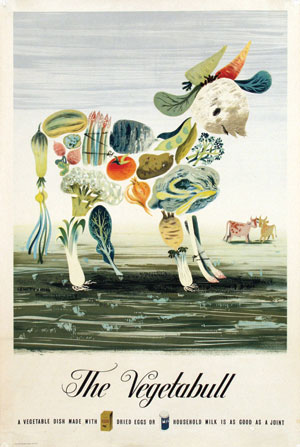

While its possible to argue that other posters like the Vegetabull have elements of surrealism in them, they have exchanged the true strangeness of surrealism for a cosy humour.

I’d call that whimsy instead. Humour was a favourite way for the British to cope with the war, and whimsy was a way of dealing with the surrounding surrealism, of defusing it.

Only after the war could the true strangeness of surrealism – and its underlying fears – be looked at properly, because, finally, it was safe to do so. Designers can choose to be odd and uncanny because the world around them no longer looks like that.

Indeed choosing to recreate this disorder in a controlled way, these designs are, in a small way, healing some of what has happened during the war.

So the way that surrealism flourished again for a while in the late 1940s and the very early 1950s makes perfect sense. Which only leaves one big question, why this did not happen in art as well? Or was Herbert Read wrong? I’m not enough of an art expert to answer that question one way or another, but there are enough British surrealist paintings about to make me suspect that he might have been.

Perhaps everyone was too busy looking at Paris and New York to have noticed. But here I am treading into areas which I don’t really know about – so if anyone else has some thoughts on this, I’d love to hear them.

This, by John Rowland Barker (aka Kraber) is a little surrealist:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/portsmouth-future-24440

That is rather good as eel, isn’t it. It has the air of a mural produced for post-war rebuilding, I wonder if that is actually the case?