Exhibits A and B for today’s argument come from eBay.

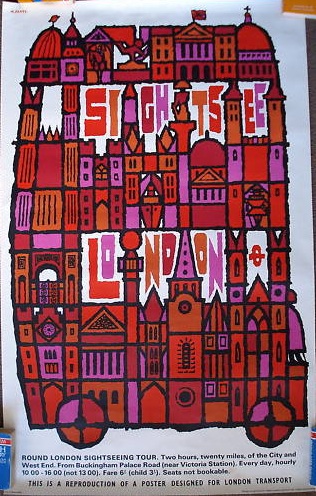

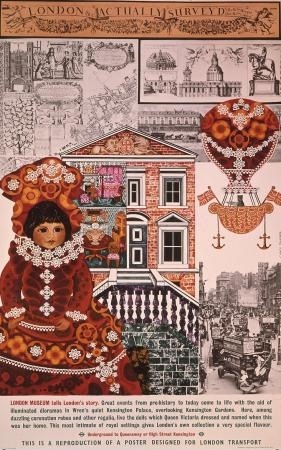

This is a London Transport poster by Abram Games from 1968.

Except it also isn’t. Here’s the description from the listing itself.

“Sightsee London” by Abram Games 1968. This is an authentic LT poster printed by Sir Joseph Causton & Sons in 1971 for sale in the LT shop and carries the line “this is a reproduction of a poster designed for London Transport” – it is not a recent reprint.

So, I don’t want to buy it because it says all over the bottom that it’s a reprint. An old reprint, true, almost as old as the original poster, but still a copy.

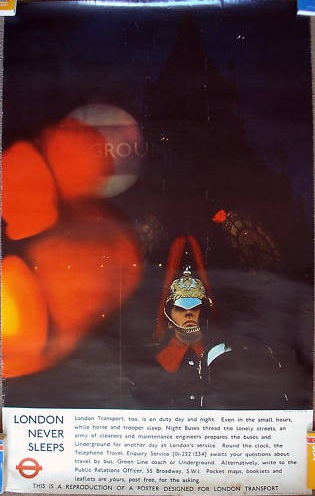

There’s another one too, a rather natty bit of swinging 60s design.

And I’m not going to buy that one either, for just the same reason.

But why should this matter? It’s still an old poster. Come to that, why don’t I buy a giclee print of whatever poster I fancy instead of spending time and money in pursuit of the originals?

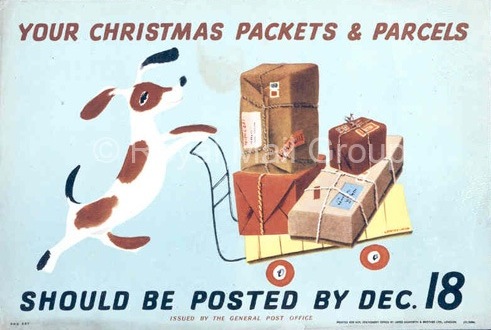

Mr Crownfolio asked that question the other day, and I didn’t have a good answer. If we buy posters for the good design and because they are lovely images to have around, a reprint, of any kind, shouldn’t be an issue. I could have this Lewitt Him for £30 from Postal Heritage Prints,

which is considerably cheaper than the amount we actually paid for an original copy. And yet I still don’t want it. Why is that?

There are some relatively straightforward answers, like the thrill of the chase and the bargain, and that the originals will make much better investments. That’s all true, but there’s more at stake here than that. And to explain it, I may have to use some theory (but don’t worry, there will be nice pictures as well along the way).

Back in 1936, the critic and writer Walter Benjamin (in an often-quoted and pleasingly short essay called ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’) argued that the original work of art had an ‘aura’ – its presence, uniqueness, history and associations. Now this, for me, is what an original poster offers. Its past life, its direct connection with the artist and their times, its apparent authenticity compared to a giclee print, all of these make a poster more interesting than a later copy.

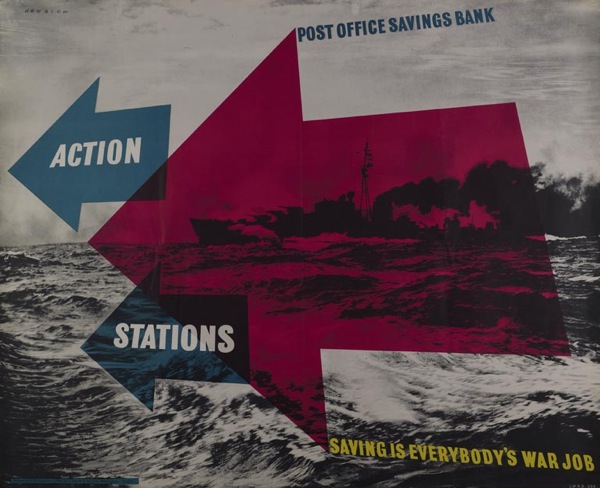

F K Henrion, Post Office Savings Bank poster, 1944

Seems sensible, but it would have had Benjamin foaming at the mouth with fury. He believed that even fine art works would lose their aura once high quality printing and photographic reproduction could make them accessible to everyone; while modern creations like films and photographs (and, by implication, posters) would have no aura at all, because there could be no original.

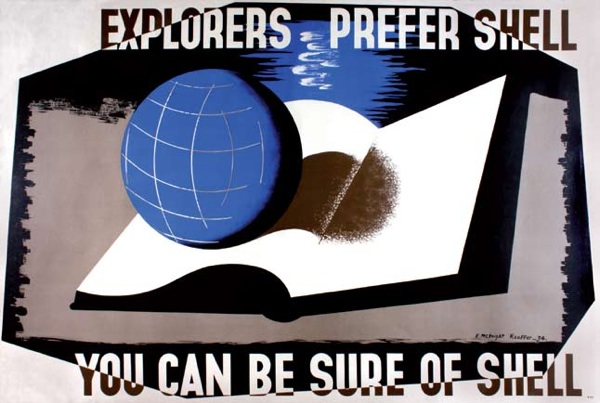

McKnight Kauffer, Explorers Prefer Shell, 1934

And without an aura, he thought that art would have to change entirely. Being of a Marxist persuasion, he thought that it would have to be about politics instead of reverence for the individual work. Which is why he’d be so infuriated by my faffing about, worried about which London Transport posters are original and which are not. Somehow (the mighty and indistructible powers of capitalism in all probability), we have managed to transfer all of our myths and beliefs about individual art works on to these reproduced, never-original copies. Benjamin must be spitting tacks.

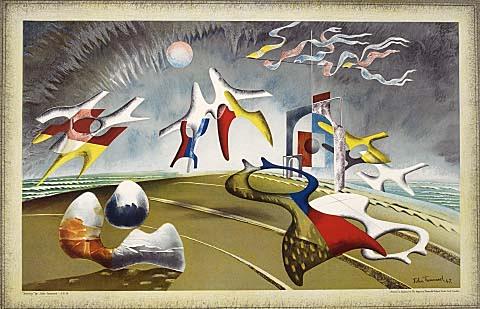

John Tunnard, Holiday, School Print, 1947

The sad thing is, he came quite close to being right. In a very British, watered-down way, ideas like the ‘School Prints’ series were an attempt to put his theories into practice. In the late 1940s, fine and avant-garde artists including Henry Moore, Picasso and Braque created lithographs that were designed for reproduction and offered to every school in the country, making the best of modern art available to everyone who wanted it (nice article here if you want to know more). These artworks were designed to be reproduced, in theory infinite in number, just as Benjamin would have liked them to be. This should have been art without an aura, easily encountered on the walls of schools and hospitals rather than art galleries, in a political gesture very typical of the egalitarian post-war period.

Michael Rothenstein, Essex Wood Cutters, School Print 1946

But, of course, it didn’t end up as he had hoped; we now collect them, value them, treasure them for their limited availability. The Henry Moore is worth close on £1000. If you can get hold of a copy of course.

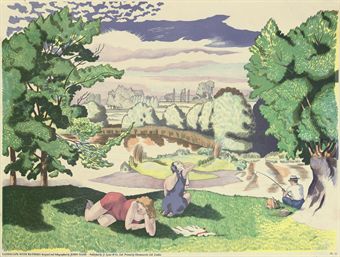

The School Prints were not alone either. The late 40s and early 1950s were a Benjamin-esque frenzy of art for all. Lyons Tea Shops commissioned prints from modern artists between 1947 and 1955 with much the same motivation. (Like the School prints they are now valuable, collectable unique items. There is a slew of them on offer today at the Christies auction, as mentioned a few weeks ago.)

John Nash, Landscape with Bathers, Lyons print, 1947

And I’ve already blogged about the way that London Transport Shell and the GPO commissioned fine artists and avant-garde designers to design their posters both before and after World War Two with some of the same motivations. Art was no longer the preserve of the privileged, it needed to be made available to everyone in this new, modern, reproducible world. All these prints and posters were Benjamin’s theories made flesh.

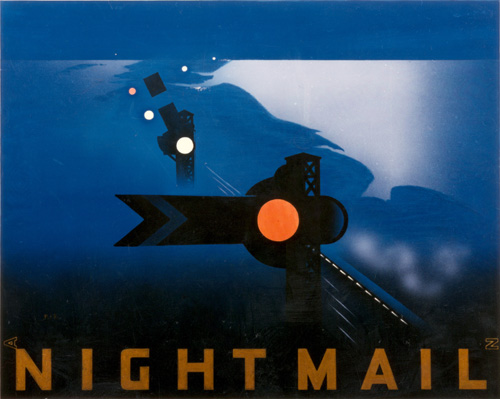

Pat Keely, Night Mail, GPO, 1939

But each and every one of these objects are now unique, collectable, valuable. They’ve all acquired an aura. And so I do mind whether or not I get a print, whether my poster was printed in 1968 or 1971. I am, frankly, a lousy revolutionary.

Two other points to bear in mind. One is that I used to work in a museum, so there are other reasons for collecting old things as well. I’ll blog about them one day too, when I’ve articulated what on earth they are.

I also need to admit we’ve bought a couple of these reprints before now. Like this Carol Barker.

(I’d like to blame this on initial naivete, and some slightly dodgy eBay listings, but I think lack of attention to detail may have had something to do with it as well. Repeat after me: I must read descriptions more carefully.)

Once again, the reprint is only a few years later than the ‘original’ but it still wrong and we’ll probably sell it on at some point. Walter Benjamin would be very disappointed in me; I just can’t help seeing auras.

Apart from the aura of an original, I think the quality or appearance of a reproduction seldom lives up to an original, although modern technology has improved this. Reproductions are also often reduced to more manageable dimensions which can reduce their impact.

Have you ever had an LT reproduction next to an original? How different are they? Same size? Same paper? Same printer? Why indicate that it is a reproduction?…

And another thing…I’m sure I have seen occasional examples of old railway quad royals printed on thicker, superior paper than usual, presumeably contemporary with the standard versions but for exhibition purposes. Are these originals? (I think there was a collection of Norman Wilkinson posters sold at Christies some years back that were like this)

The London Transport posters are originals!

They were overprinted with the text and distributed for, I guess, educational purposes. The text may also denote posters that were sold through the LT shop in London.

One of the interesting things about Benjamin’s essay is that it refers to work that, by todays standards, would be understood as craft based.

One of the problems with posters is their scale. So, people often print them small as they can be displayed conveniently. To print digital files in large scale is still quite expensive.

Part of the aura of old things is their patina. Old posters have all sorts of traces upon them.

Thank you both for the interesting thoughts.

mm: Funnily enough, I think we do have one LT poster as both a reproduction and an original, so I will compare the two and see if there are noticeable differences – and quite possibly report back on the blog. The idea of ‘exhibition’ copies is also interesting – it seems completely plausible, although I’ve never seen one. I wonder if the Norman Wilkinson ones were done for the artist himself?

Paul: completely agree about the patina, that’s so true.

What a great blog post! Thank you for this illuminating dissection of Benjamin’s essay, and for the wonderful pictures.

I think part of the reason I collect posters is because I’m attracted to the ‘survivability’ of these otherwise ephemeral objects. Posters are supposed to be rain-splashed and torn down, so I wonder whether their survival, which goes against their intended purpose, imbues them with a kind of ‘aura’.

T

What do you reckon about the value of a poster that has had museum quality archival restoration imposed upon it?By putting it onto a canvas backing and removing all the folds and having the rips repaired to an exacting standard of the original is it as valuable as one which has its patina of time?Is it still an original if another person has restored it?

That’s a really interesting question, and one which I don’t think has a right answer.

I can think of arguments for both sides. If the poster is cleaned and flattened, you are able to see it and appreciate what it is trying to do, and I don’t think many people would have a problem with that. But I think – and museum people please do correct me if I am wrong – that museums these days prefer not to have their posters mounted, and for any work that is done on it to be reversible (learning a lesson from oil paintings where many misguided restorations of the past have ruined an artwork beyond repair). But as a person, not a museum, I’d rather have something which is pleasing to the eye, and clean and flat is definitely more pleasing to me. Perhaps you can have too much patina sometimes

But once you get into the realms of retouching and repairs, it’s a very different matter, and it’s a matter of judgement here whether a restorer is adding to the value or detracting. Having said that, we have a Tom Purvis poster which had some bites out of the sides. It’s been restored for framing, but these were just patches of flat colour, and the restoration makes it very clear where they have been replaced. We wouldn’t have the poster up otherwise (and wouldn’t have been able to afford it had it not been a bit battered). so in that case I am all for it.

Carol Barker illustrated ‘Achilles The Donkey’ to which H.E. Bates wrote the story. The Bates estate would like to find Miss Barker. If anyone can help please mail me: vickywicks@hotmail.co.uk. Many thanks.