Survivors

When I wrote about poster hoardings and their rather surprising effects last week, the comments section ended up as a bit of a debate on how posters survive. Were the few that remain only saved because the designers and a few other far-sighted people connected with their production and display collected them (the Malcolm Guest model)? Or were there more which were sold on to the public of the time as well?

I promised to go away and try and find out as much as I could and report back. There’s lots more research that can be done, so this is very much a work in progress. But by asking the questions here, I’m hoping that I might get some answers from you as well. So please do pile in if you can help.

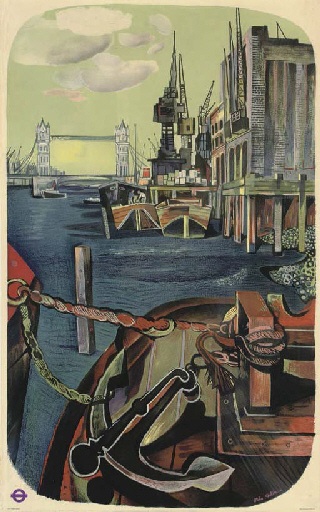

John Minton, London’s River, 1951

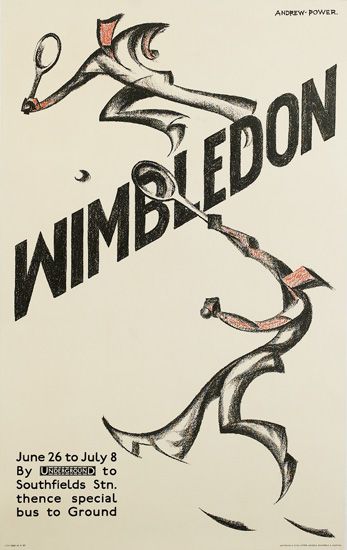

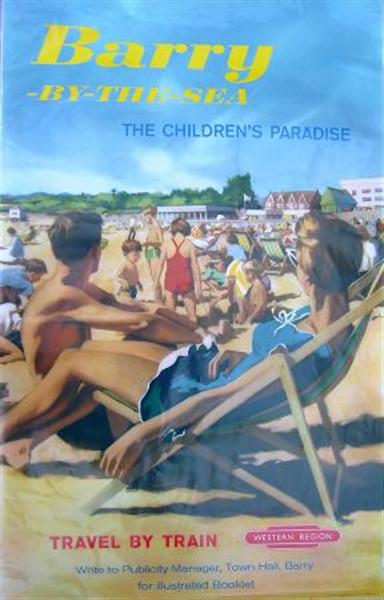

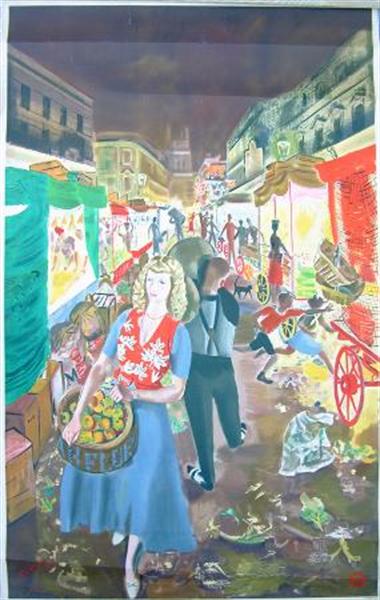

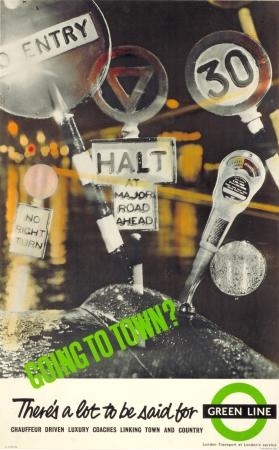

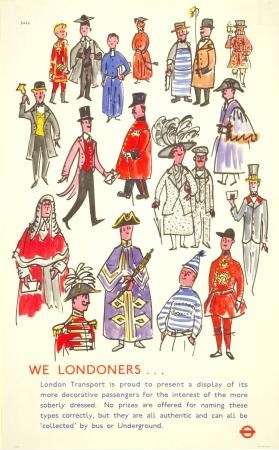

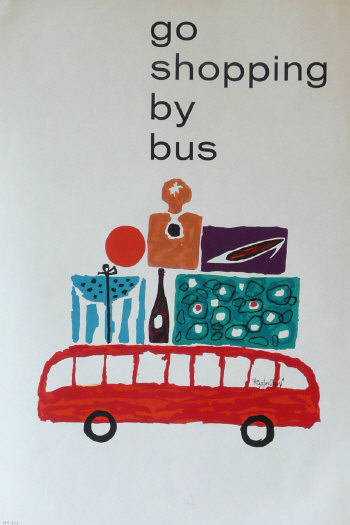

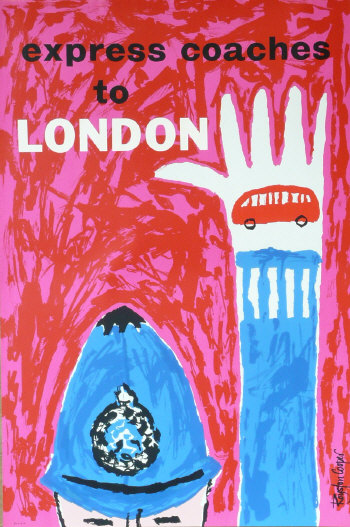

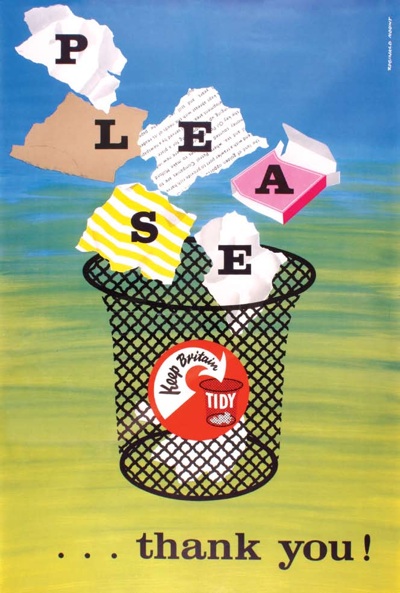

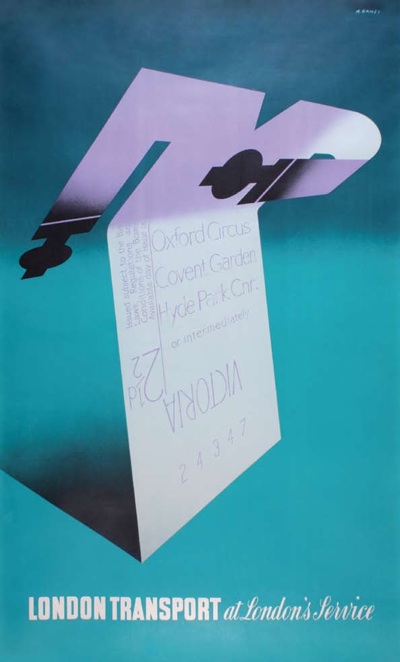

What strikes me is that some kinds of posters survive in disproportionate quantities. Any auction, or even a look at eBay will show you a lot of London Transport posters or railway posters, with lesser amounts of Shell and Guinness items too. But very little British commercial advertising survives at all – you can go through swathes of auction catalogues without seeing any for months or even years.

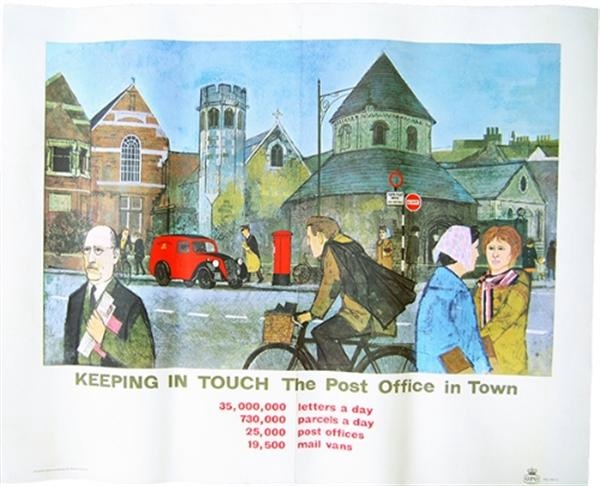

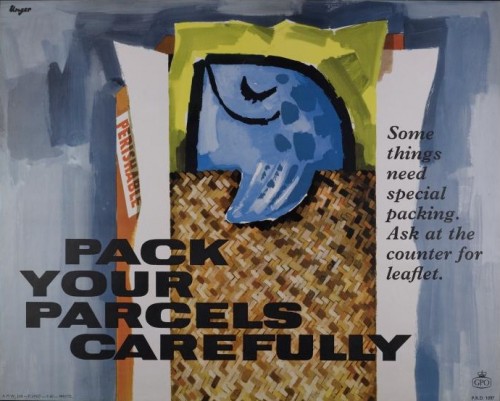

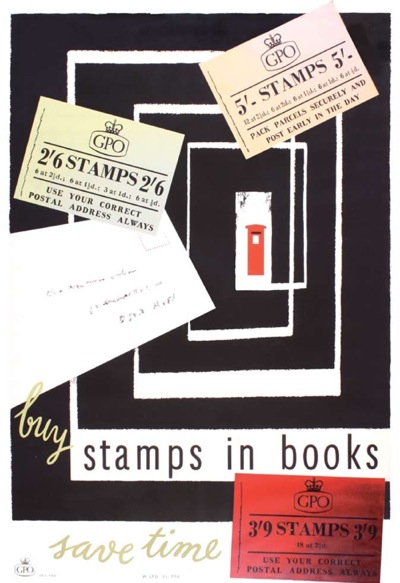

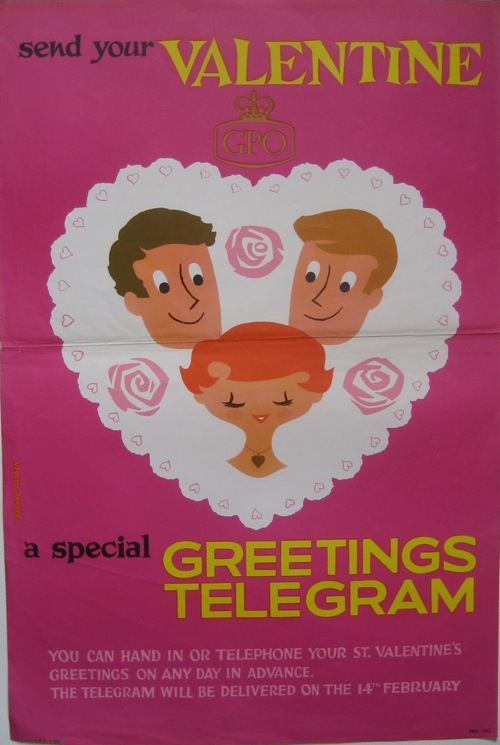

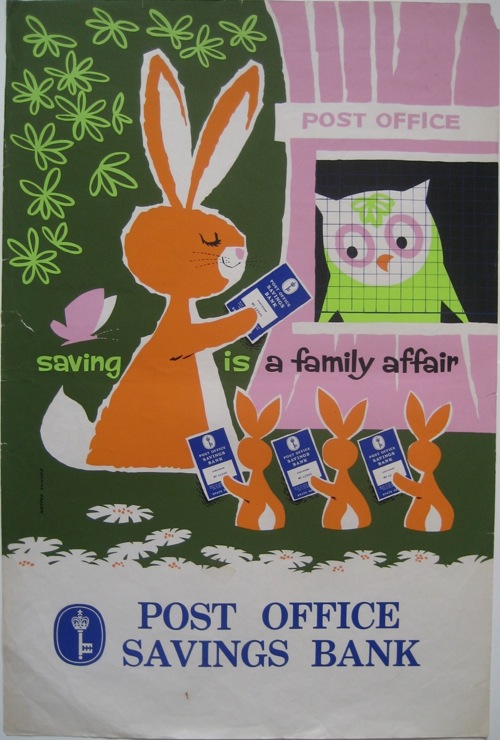

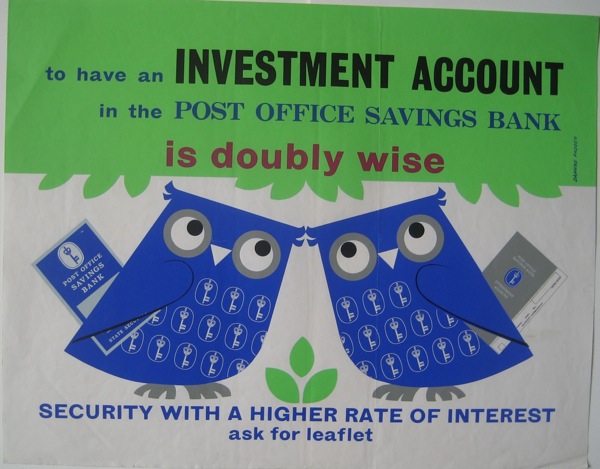

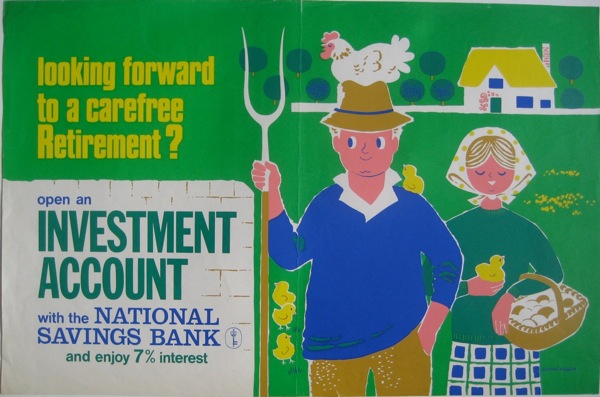

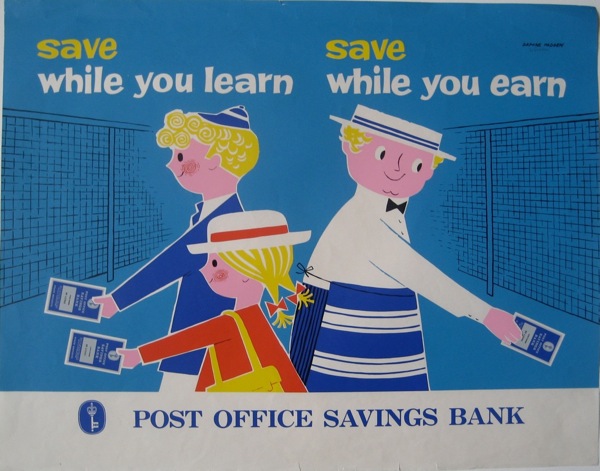

The same is true of GPO posters – which are examples of great design but nonetheless come up very rarely. (To give you an idea of how rarely, Christies catalogue archive can turn up only 10 or so GPO posters which have come up for sale. Put in “shell poster” and you get hundreds of results. I daren’t even type in railway poster.)

So my suggestion would be that the kinds of posters which survive in numbers were also sold on to the public one way or another.

There is no dispute that this is what London Transport did (as mentioned on here before). Here’s Oliver Green of the London Transport Museum on the sales pattern in the 1920s:

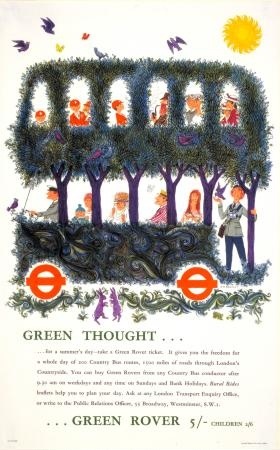

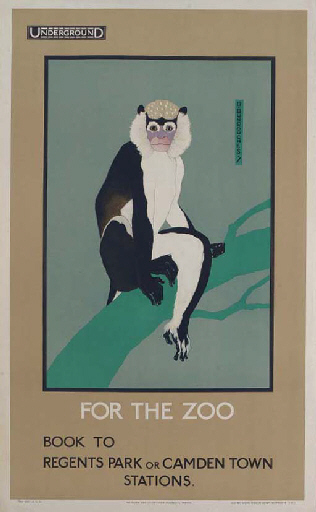

A typical print run in the 1920s was 1,000, of which 850 were required for posting on the system where they were displayed for one month. The remaining 150 copies were available for purchase at the company’s head office for between about two and five shillings, depending on the printing cost. Posters in demand with the public were invariably those which followed the more traditional artistic designs, such as Gregory Brown’s St Albans, Fred Taylor’s Kew and Dorothy Burroughes’ For the Zoo. These three were all in the top ten of a bestsellers’ list which was announced by the Underground in 1923.

Dorothy Burroughes, 1922

By 1931 the best sellers were selling over 300 posters each, and London Transport were selling a total of 10,000 posters in a year. But even the modern art posters did sell to some.

Edward Bawden has also recalled that he and Eric Ravilious, when students together at the Royal College of Art in the 1920s. looked forward eagerly to the appearance of a new Kauffer Underground poster which was then, literally, one of the cheapest forms of good modern art available.

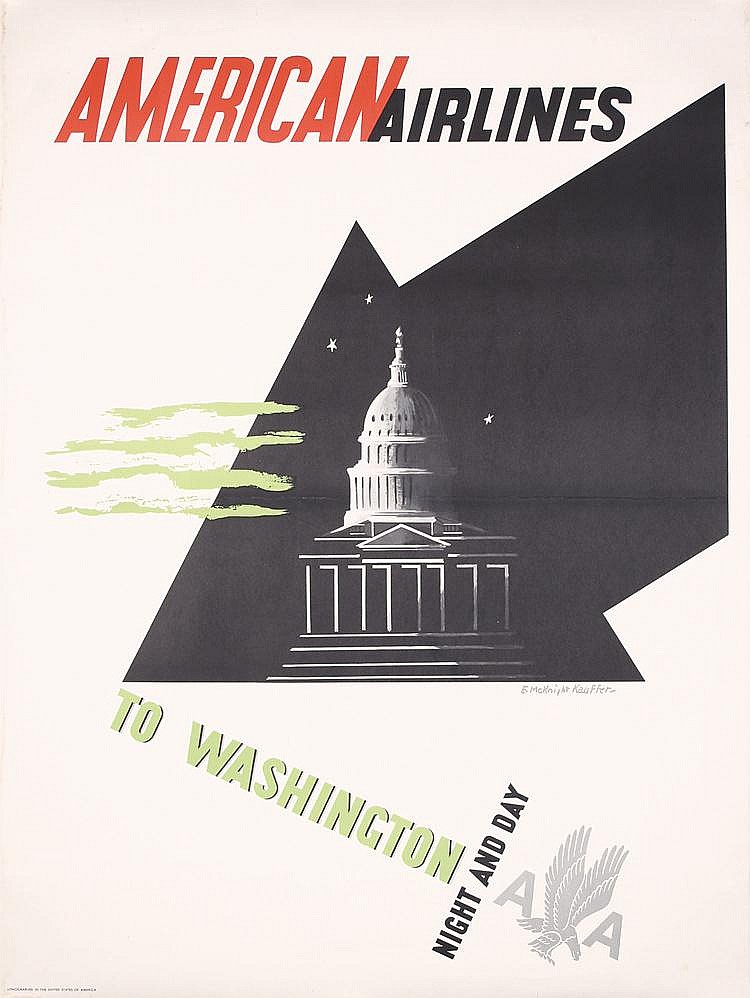

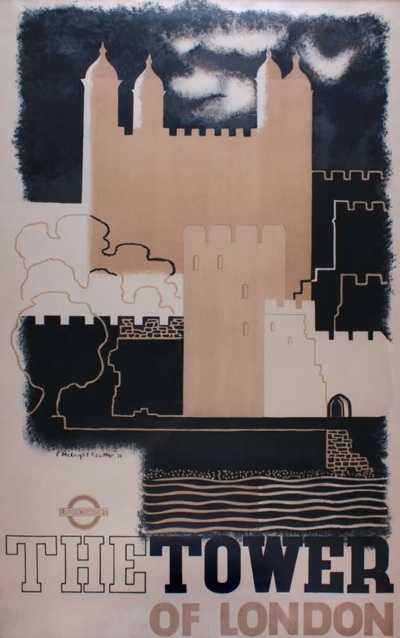

McKnight Kauffer, 1934

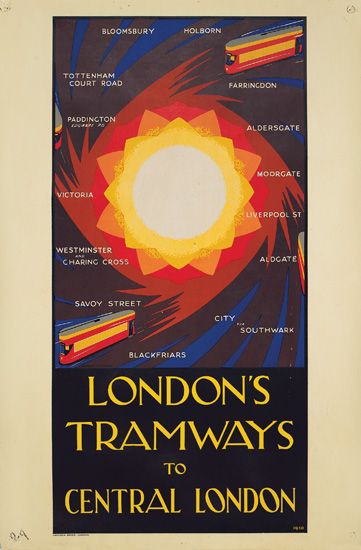

In 1933 the London Transport poster shop opened in their headquarters at 55, Broadway, and designs were, it seemed, commissioned specifically with shop sales in mind.

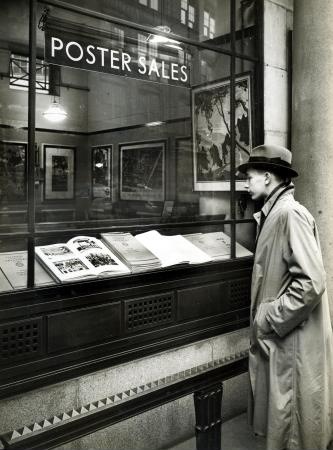

London Transport shop,c.1935.

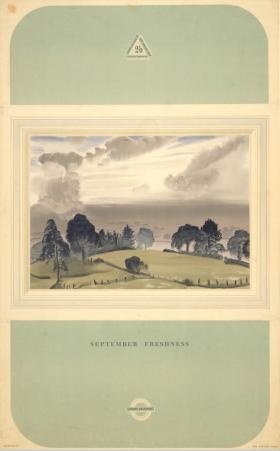

Furthermore, some posters were also created so that they could be easily cut down for framing and display in the home.

Laura Knight, September Freshness, 1937

Poster sales continued on and off, with a break for the war, sometimes only to schools and other educational establishments, sometimes to the public. Claire Dobbin writes about it in some detail in her essay in London Transport Posters if you want to know more.

She also mentions is that London Transport held poster exhibitions too, at Burlington House in 1928 and the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1949.

London Transport poster exhibition at Burlington House, 1928

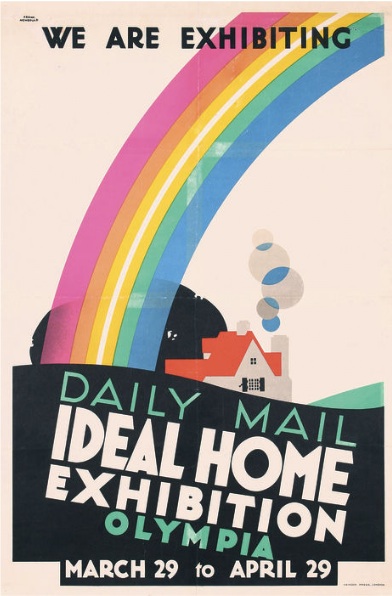

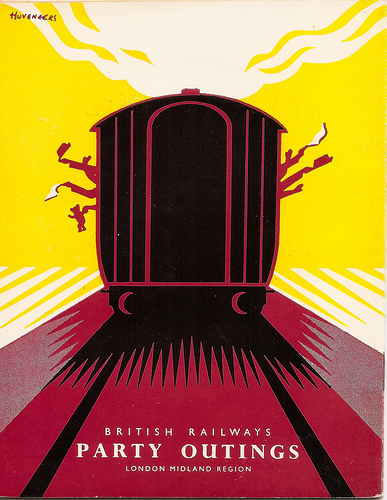

For London Transport, these were infrequent special events, but in the case of the railway companies, exhibitions were a regular feature of their promotions. David Watts catalogues them in the essay I was referring to the other day.

Annual poster exhibitions were held at the LNER’s King’s Cross station in London between 1923 and 1927. Between 1928 and 1933, with the possible exception of 1931, they were held in either the New Burlington or Grieve’s galleries in the West End. In 1936 a private exhibition was held in Marylebone, presumably at the LNER station. In 1937 the exhibition reverted to the West End. LNER poster exhibitions were held annually in Edinburgh between 1924 and 1938. Their exact location is not stated, except for 1935, 1937 and 1938, when it was Waverley station. Numerous other localities hosted occasional LNER poster exhibitions, including: Aberdeen (1929–30, 1934), Barnard Castle (1934–36), Bournemouth (1934), Bradford (1934–35), Brighton (1936), Cleethorpes (1935), Dundee (1934), Gateshead (1936), Glasgow (1929–30), Grimsby (1934), Ipswich (1935), Kingston upon Hull (1932–36), Leeds (1934), Lincoln (1934, 1936), Manchester (1935–36), Newcastle upon Tyne (1930, 1934–36), Norwich (1933), Shef?eld (1933, 1936–37), Yarmouth (1934) and York (1932–36). […] It is likely that other localities also hosted exhibitions of LNER posters and that those listed above held them in more years than shown here. Exhibitions seem not to have been systematically recorded.

That’s quite a lot of exhibitions.

Now, I can’t lay my hands on any proof that posters were sold at these events. But posters were definitely sold by railway companies. Pre-war artists had contracts which paid them for every copy sold to the public, for a start.

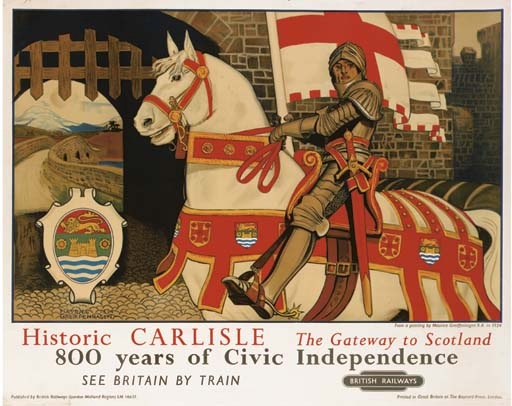

And the LMS marketed posters to the public – possibly by the same system of writing in as London Transport used. When the company produced a series of posters designed by Royal Academicians in 1924, they “sold well”, and Maurice Greiffenhagan’s image of Carlisle was top of the pops, selling to the public “in large numbers”.

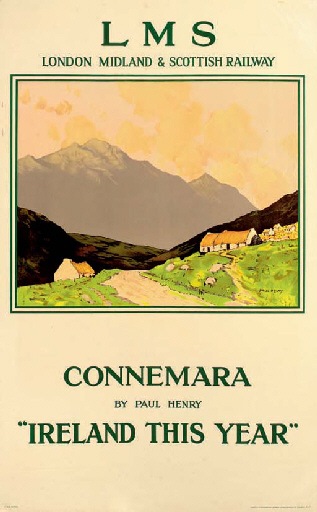

In 1931, the LMS even published a list of its six best-selling posters. Like the railways, traditional art was what the public wanted to buy, with Paul Henry’s views of Ireland taking the top two places.

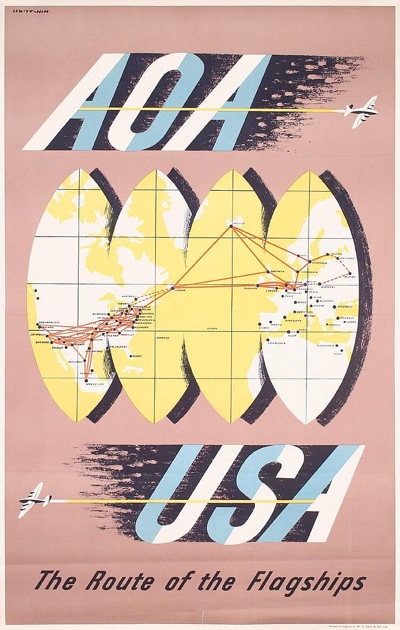

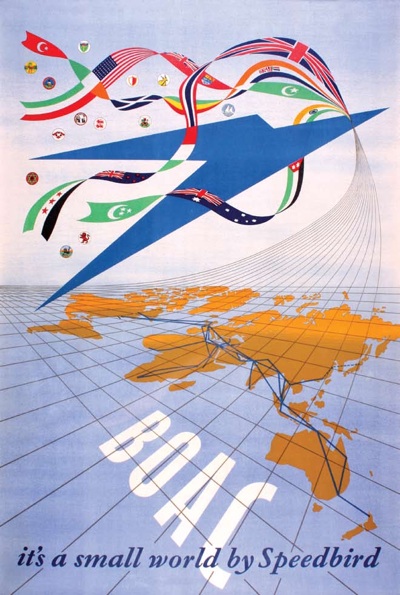

So railway posters were definitely for sale. Which just leaves Shell and Guinness posters to account for.

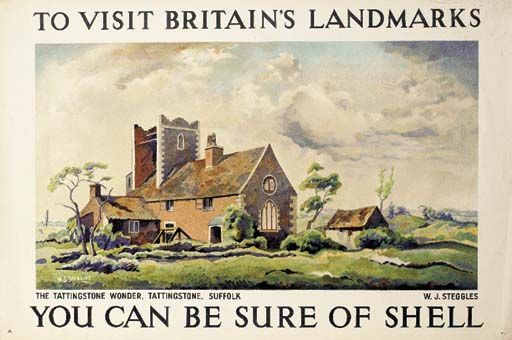

W Steggles

Shell held exhibitions of its advertising too. The first was at New Burlington Gardens in 1931 and then later they were held at Shell-Mex House and around the country. These were reviewed in the press and attracted thousands of visitors. And, yes, the posters were for sale. Michael Heller has reseached Shell’s inter-war corporate branding.

Its posters rapidly became collectors items, available by subscription from Shell or through its popular published catalogue collections.

Which just leaves Guinness posters, about which I can find out nothing right now. But I think I might be prepared to make a guess that they also were sold given that they survive in the numbers they do.

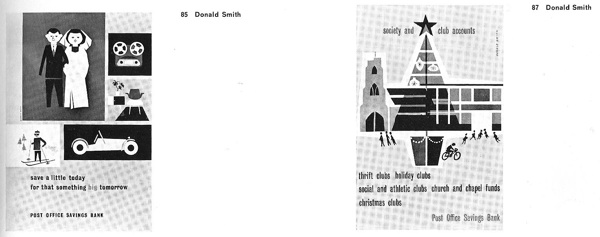

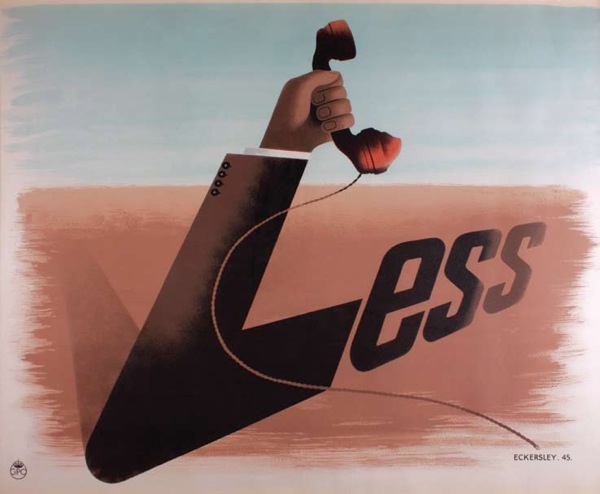

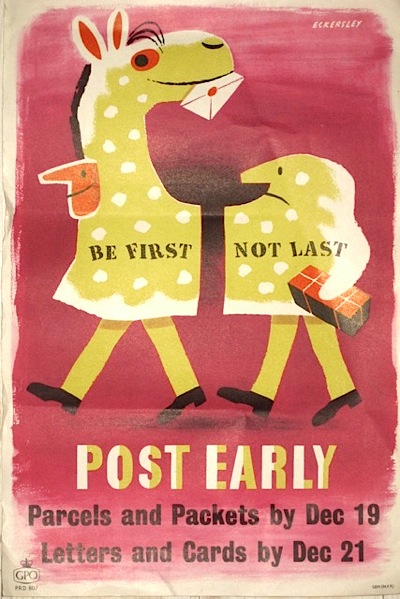

By way of a contrast, let’s go back to the GPO posters. We’ve got a fair number (in fact a rather embarrassing quantity), but what’s interesting is that I know the direct provenance of most of them. A few came from the Malcom Guest collection, a few more (all by her) from Daphne Padden’s estate. But the greatest number came from eBay, sold by a man whose uncle went to his local post office in the early 1950s and asked if he could have their posters when they’d finished with them. They’re not just floating about like the railway and London Transport posters, only thanks to rare and chance collections are they kept.

Tom Eckersley, 1955

Which makes me think that we’re very lucky that Shell, London Transport and the Railway Companies wanted to improve the nations taste by selling posters. Otherwise practically nothing would survive.

Sources

I haven’t given references in this, mainly because footnotes and blogs don’t mix well. But most of the information came from these books:

London Transport Posters: A Century of Art and Design

Underground Art: London Transport Posters, 1908 to the Present

Art for All: British Posters for Transport (Yale Center for British Art)

as well as from Michael Heller’s paper, Corporate Brand Building at Shell-Mex Ltd in the Interwar Period. Do ask if you want any more detail and I will do my best.