I have on my desk two books, a thick one and a thin one. The thin one is Melanie Horton’s book on the Empire Marketing Board Posters at Manchester University. But, rather counter-intuitively for a Friday, I’m going to go for the doorstop sized one instead, which is Distinction

by Pierre Bourdieu.

It has been, I discovered today, voted one of the most influential sociological books of the 20th Century. Wikipedia can summarise it, as they do this rather well.

Bourdieu discussed how those in power define aesthetic concepts such as “taste”. Using research, he shows how social class tends to determine a person’s likes and interests, and how distinctions based on social class get reinforced in daily life.

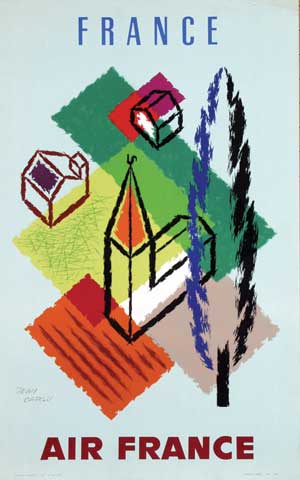

Jean Carlu, 1958

He does this by micro-analysing the taste and cultural choices (whether that’s music or interior design) of a vast number of French families and people in the early 1960s, over 500 pages and with myriad tables, diagrams and interviews.

I was forced to read it as part of my Design History course. But I’m actually rather glad I did. Because although the book is undoubtedly ‘very French’ (as the translator’s foreword warns) his approach is also a very useful way of thinking about design. It earns its keep simply by reminding us that there is no such thing as pure good design or taste, that everything we choose, or turn away from, is a determined by class and culture as well as our own personal preferences.

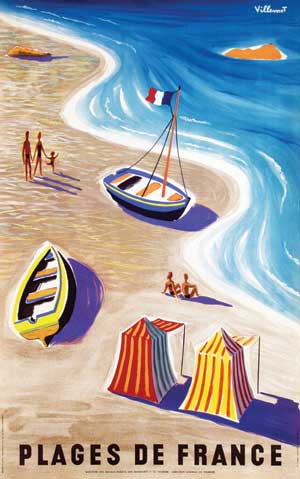

Bernard Villemot, 1955

That’s not the only reason why I’m writing about it here, though. The book may also answer the question, why do I (why do we?) collect posters? I will try to distill the argument from his rather dense and sociological prose to see if it stands up.

One of his key ideas is that the ruling classes don’t just have economic capital but also social and cultural capital. While the first two can be acquired, cultural capital tends to be inherited. And he argues that it is perhaps the most important means by which social classes differentiate themselves. (For example, if you have economic capital, but no cultural capital, you will tend to be pigeonholed as nouveau riche).

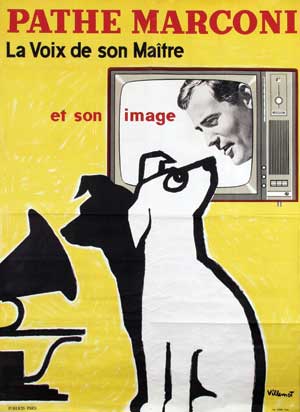

Paul Colin, 1945

But what’s great about the book is that he microanalyses these ideas and how they work in real life. So, he points out that while many people agree on the cultural capital of appreciating art, there is a big difference between the middle classes who go to see it in a museum, and the very small fraction of the upper classes who own it themselves.

The appropriation of symbolic objects with a material existence, such as paintings, raises the distinctive force of ownership to the second power and reduces purely symbolic appropriation to the inferior status of a symbolic substitute.

Roughly translated, too many people are able to ‘appreciate’ a Leonardo da Vinci painting for it to be exclusive enough. But if I own a Leonardo, I can lord it over you and feel superior, because you may only go and see in in a museum. In visiting a museum, you’re trying to reproduce the experience of owning it, but you know that this isn’t as good. I think that’s probably as true of the English upper classes than the French. After all, the English aristocracy let us into their stately homes, so that they can be certain we know that they have lots of nice paintings and we don’t.

Bernard Villemot, 1960

He also argues that art objects are particularly key examples of the way the upper classes distinguish themselves, because while they take a long time to know about and appreciate properly, they are, in the end, pointless.

[I could type that bit out but it’s fairly headache-inducing, let me know if you want to see it, it’s on p281 of my edition.]

Nonethless, the upper classes don’t get it all their own way. These views can be challenged or subverted. And the people who are most likely to do it, are those with plenty of cultural capital but less material capital. Plenty of good taste, but no money. The problem – as Bourdieu sees it – is that these people like ‘good’ art but can’t buy it.

But in the absence of the conditions of material possession, the pursuit of exclusiveness has to be content with developing a unique mode of appropriation.

The trick is to find ways round this, either by liking things differently or – and can you see where this is going – liking different things.

Intellectuals and artists have a special prediliction for the most risky, but also most profitable strategies of distinction, those which consist in asserting the power, which is peculiarly theirs, to constitute insignificant objects as works of art.

So if I can’t afford a Picasso, I’m damn well going to go and define something else as a work of art. And then own it.

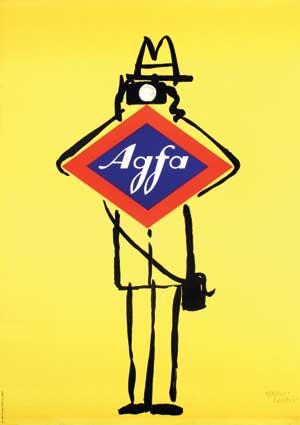

Herbert Leupin, 1956

Now, Bourdieu wrote the book in 1962, and I would argue that there are more people than just intellectuals and artists playing this game now. More and more people have no choice. Fine art prices have risen so much that only oligarchs can think of buying the real thing these days. Yes you could go down the Walter Benjamin route and buy yourself a print – and plenty of people do. But not everyone wants to do that, for whatever reasons. (In my own case, Bourdieu would blame the accumulation of cultural capital caused by a spell at art college, with the distinct lack of economic capital caused by the kind of career which results.)

So if we (if you are with me on this) want to buy art, we have to designate something else as art. So how about posters? They are originals, they are limited, they have the patina of age. We can collect them and display them in our homes, we don’t have to go to galleries to see them. We can, in short, be as upper class and tasteful as we like without having to pay a million pounds for the privilege.

Herbert Leupin, 1952

I think that there are a few peculiarly British twists to the story, though. One is the way that the left-minded section of English upper-middle classes have always rather enjoyed defining themselves against the aristocracy, and so have repeatedly embraced modernism as deliberate snub to posh people’s gilding and decoration (the Herbivore tendency of the Festival of Britain is a classic example of this kind of person in operation). The other is the simple fact that the British tend to have a very small aristocracy (compared to the French bourgeoisie) and a huge, squeezed middle class that can’t afford a grand house and a Van Dyck and there have always been a lot of people who to find another way round good taste.

If that’s fascinated you and you’d like to read the whole darn thing, well you can, here, thanks to the wonders of the internet. Don’t all rush at once.

Next week, Empire Marketing board posters from the pleasingly thin book, and, so help me, even more posters for sale.

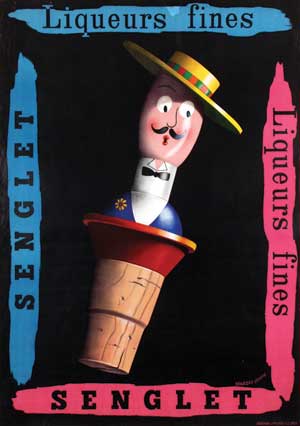

Oh, and in case you’re wondering about the images, not only are they all very French, but they’re also all for sale at the next Van Sabben poster auction on December 11th so you can buy them too. If you’ve got the material capital to afford them.

Having purchased a couple of LT reproduction posters (loudly proclaimed as such at the foot of the image) as ‘rejects’ from you & mrcrownfolio, I have followed this argument with interest. The Bourdieu text is new to me, though. And I think he has the matter in a nutshell (maybe a very large & complicated nutshell …). For me, the guiding principle is the fact that the posters were printed using the original plates & are therefore artwork just as the artist originally intended. But I am also aware of a lurking awareness of the sheer relish involved in ‘going against the flow’ & esteeming something on my own terms, an esteem that I really wouldn’t extend to a photographic reproduction – whatever its size. These latter are art without the necessary craft to make the intention & execution ‘whole’. So, I still get to be snobby about ‘Art’ but I can also afford to put these posters on my wall!

Speaking of size, though, I strongly suspect (but haven’t yet checked by measuring) that these LT repro prints are just a little bit too large to fit in a DR frame .. its that pesky legend at the foot of the image …

The Burninghams are quite lovely & I would have been proud to call them my own if I could have afforded to import them! They are something quite special (especially the umbelliferous winter landscape) … & we may never see an original … so, may you have many years of enjoyment of them & never regret your purchase!