Back in my student days, now rather some time ago, I was sent to chaperone some Belgian friends of the family when they made a short visit to London, to assist with the language and the mysteries of the London Underground. There are three things that I remember clearly from this trip: a meal out at an Aberdeen Steakhouse (an experience I have never found it necessary to repeat), seeing what was apparently ‘the last bomb site in the City of London’ on a guided tour, and taking them to the Imperial War Museum. From the last I brought back souvenirs, postcards of World War Two posters.

This has to have been one of the experiences which turned me into a poster collector, although at the time I had no idea that such a thing was even possible. I just bought the postcards and stuck them on the wardrobe door in my student rooms.

I have said this before, but it is very satisfying to now have a genuine copy of the James Fitton hanging on the wall when it was one of the ones which I had picked out as a postcard.

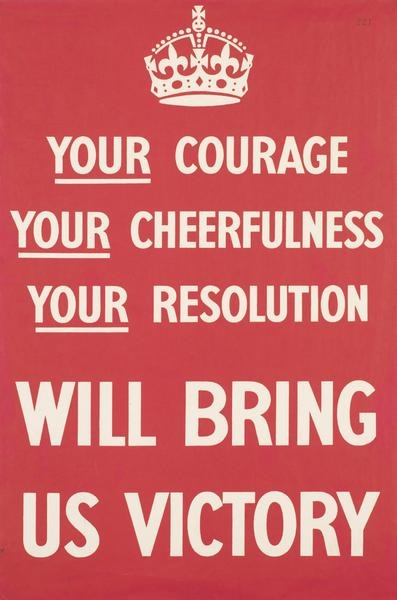

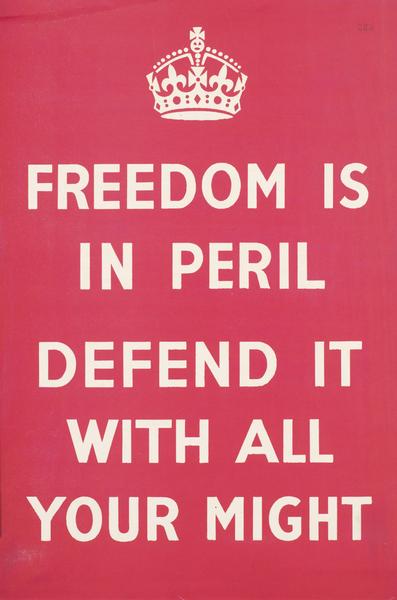

But this isn’t just an anecdote about one of the ways in which I discovered posters, I remembered it because I’ve been thinking about how World War posters are used. Both then and now, it seems that we only want to see in them a highly selective version of the Home Front experience. This is something I say about poster history often enough, but I do find these choices and omissions particularly revealing. There were a huge number of posters produced during the war, and so the relatively few we pick out end up telling us as much about ourselves and our present day anxieties as it does about the war. After all, why would we need propaganda anyway these days?

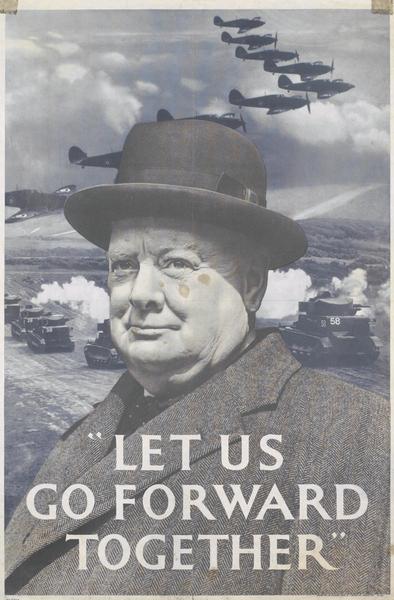

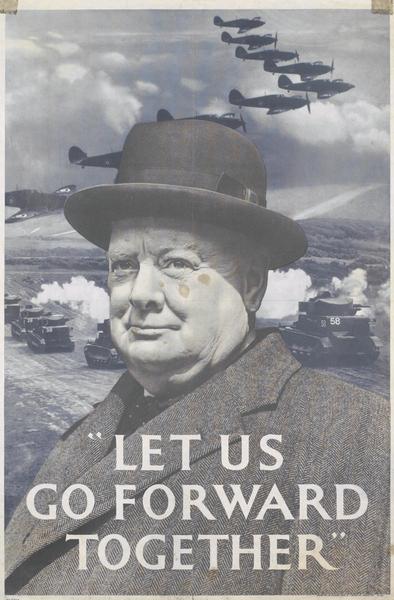

That there is a ‘myth’ around this era, a vision of World War Two as the high point of the British nation when everyone pulled together selflessly and class-consciousness disappeared in the heat of the battle, is not a new idea. It was first expounded by Angus Calder in The Myth Of The Blitz in 1991 and is now an established part of historical thinking about the period.

in 1991 and is now an established part of historical thinking about the period.

Myths don’t arise just by accident, though, they always have their uses. Calder, in his preface, is completely open about why he wants to question the established story of Britain during the War,

My anger, firstly over the sentimentalisation of 1940 by Labour apologists, then over the abuse of ‘Churchillism’ by Mrs Thatcher during the Falklands War, led me to seek, every which way, to undermine the possibility of the mythical narrative.

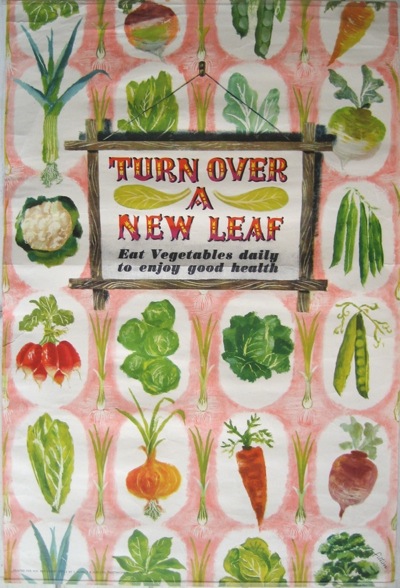

Even though Calder exposed its mechanics, the myth has refused to disappear. The darkest days of World War Two still represent an apotheosis of Britishness, and one of the ways by which we maintain this idea is through the Home Front posters that we choose to like.

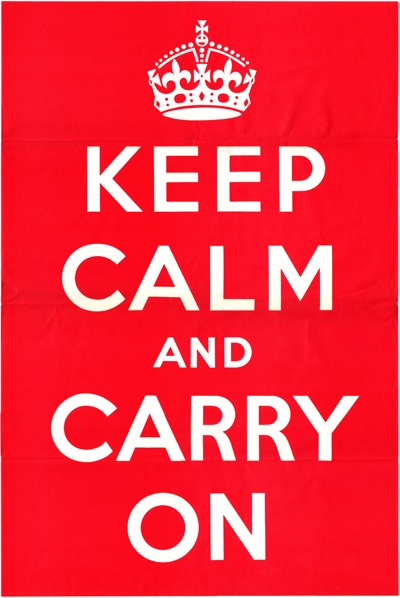

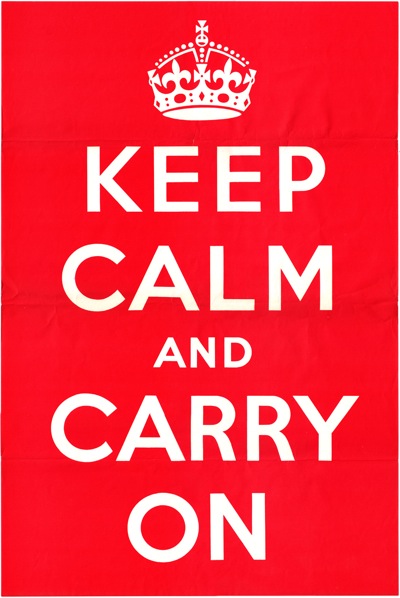

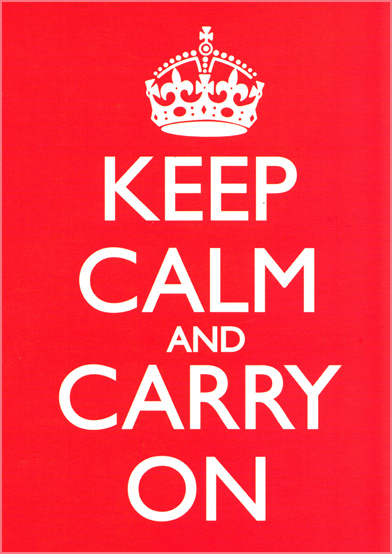

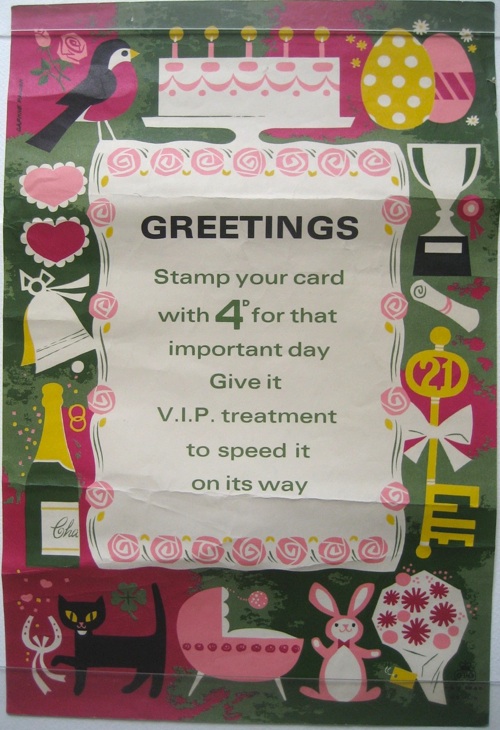

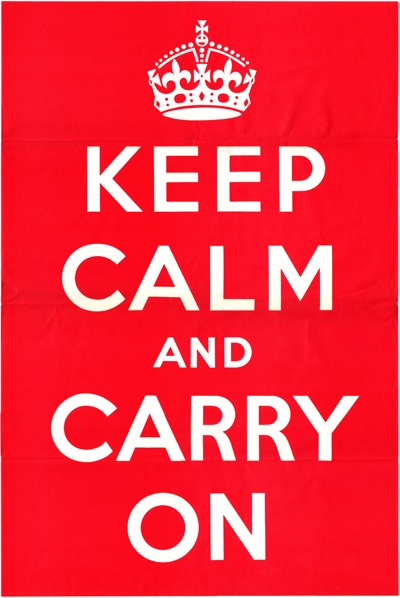

People certainly do like them. Not only do they fetch increasingly high sums at auction when they appear, but a single Home Front poster, Keep Calm and Carry On, has become the Athena poster for the start of the twenty-first century, reproduced, parodied, everywhere. So why do we want to keep repeating these stories, and what use are they to us now?

The core belief is the same as it was when Calder described it:

a myth of British or English moral pre-eminence, buttressed by British unity.

This is still the ideal which has singlehandedly sold almost every copy of Keep Calm and Carry On. But there is not just pride in our achievements here, behind it also lurks anxiety. We wouldn’t need to keep reminding ourselves that Britain was once great if that was still indisputably true. The fear is now that we may be a second-tier nation, dependent on others; perhaps also we are afraid that we have lost our traditional grace under pressure. Perhaps, even, we are afraid that if we were tested so severely again we might be defeated this time. And so we need to keep reassuring ourselves with the story of the war and how well we did.

These are thoughts which are not often articulated elsewhere in our culture. So the posters function like dreams, dragging thoughts up from our subconscious which are not quite safe to express in any other ways. Like dreams, they are visual more than verbal too, so we don’t have to put into words the ideas they express, which might force us to analyse these uncomfortable truths.

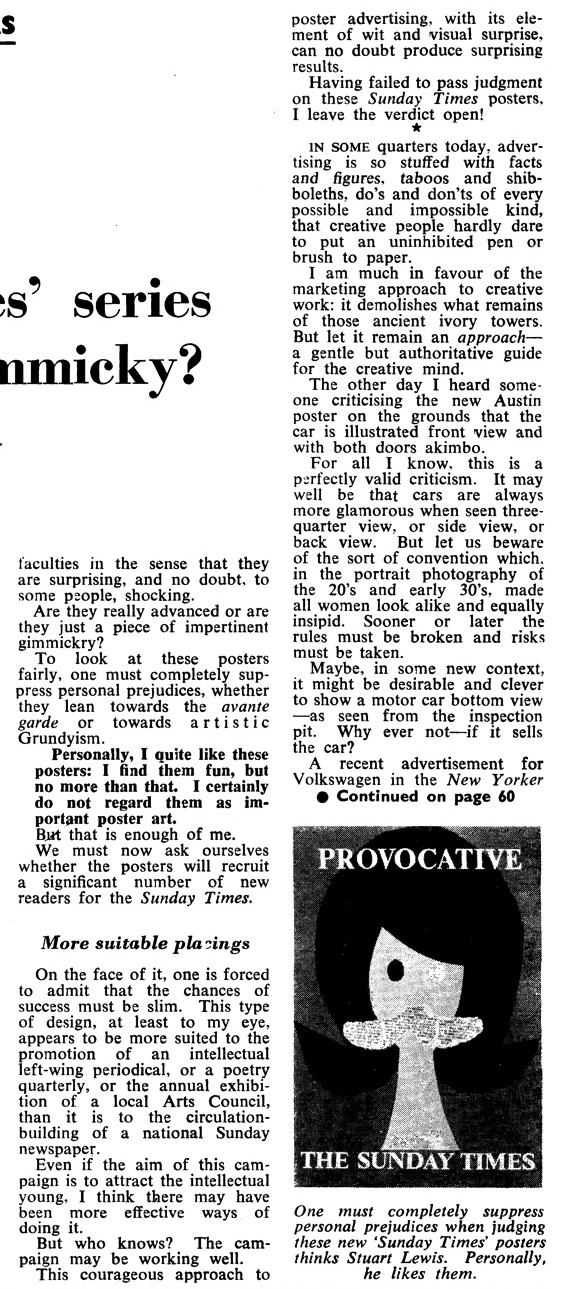

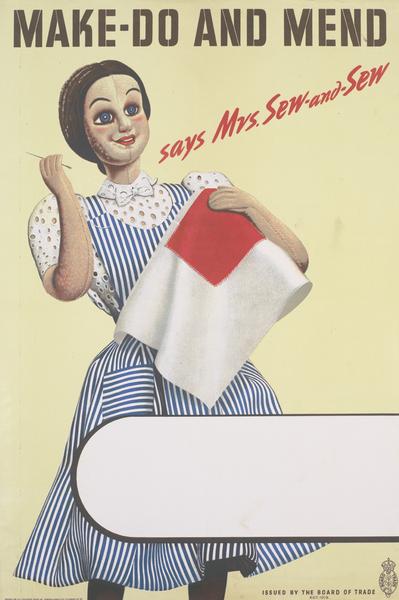

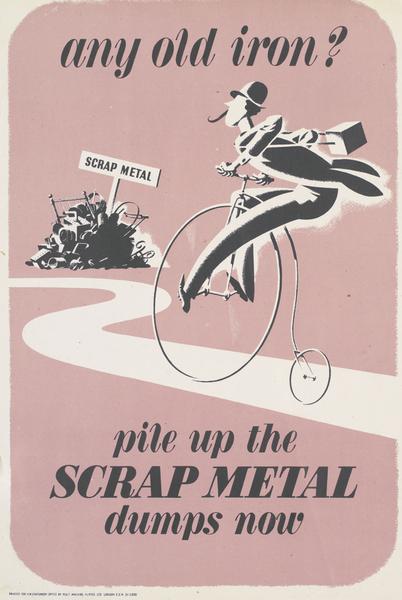

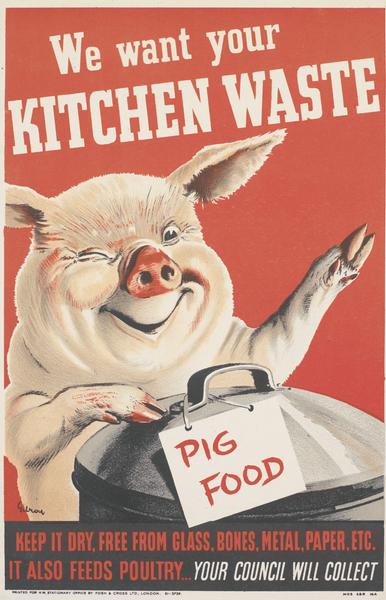

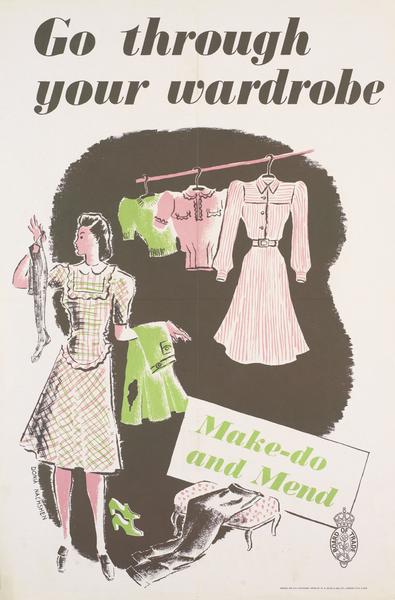

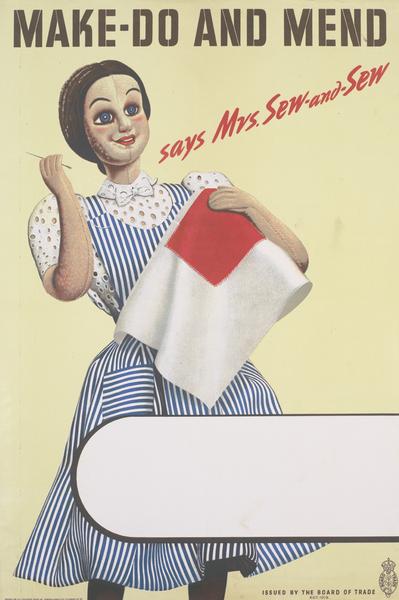

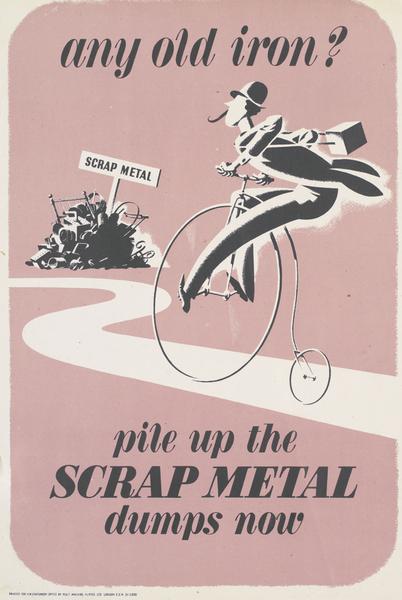

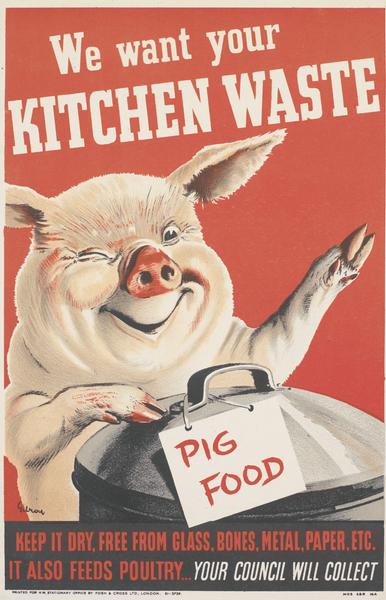

Behind other posters lurk other fears too. Still much-loved are those for the various kinds of salvage and austerity; we repeat the slogans and reprint the images.

Some of these, particularly ‘Make Do and Mend’ weren’t in fact popular then – housewives felt that they were already doing as much as they could to reuse and repair and some of the tips were therefore a bit insulting. But they are popular now. Even as we buy more phones, more fast fashion and throw more food away, we also know that we consume too much and waste too much. Perhaps we would be better people if we did not, perhaps we might even be more British.

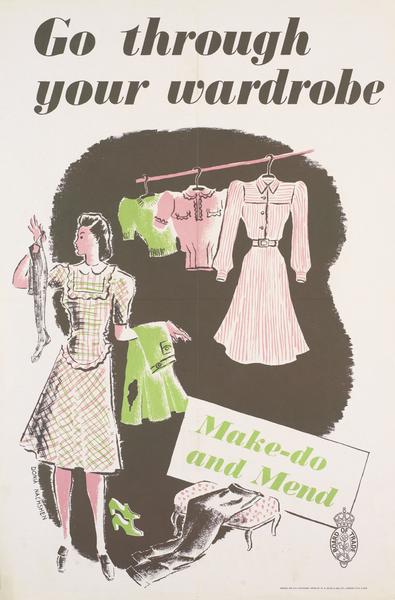

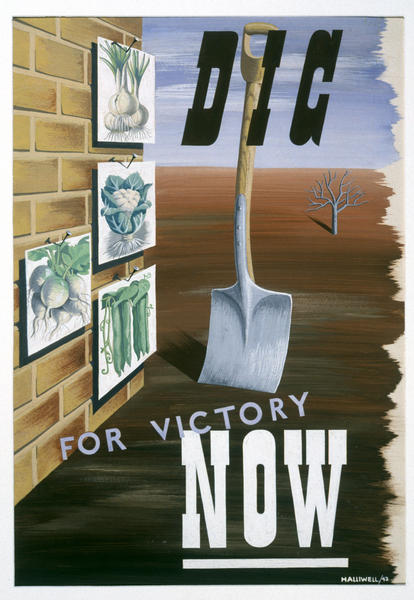

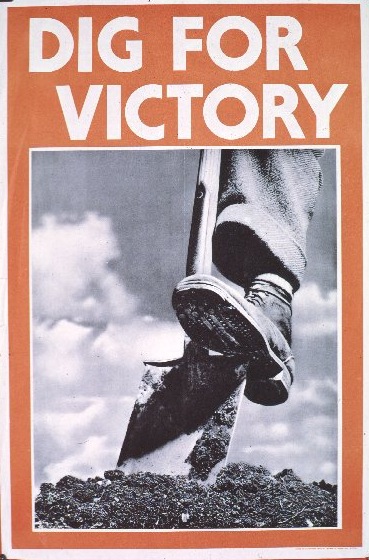

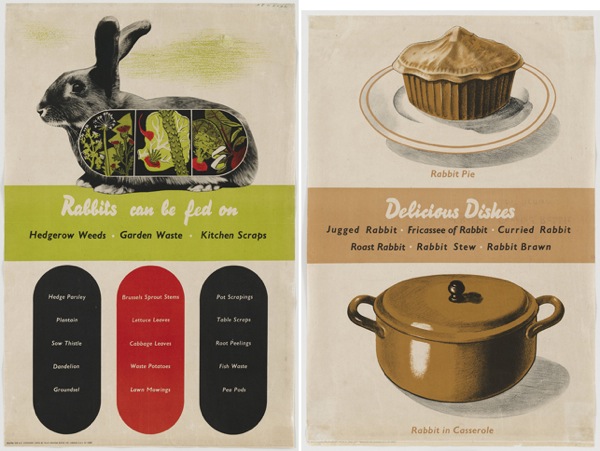

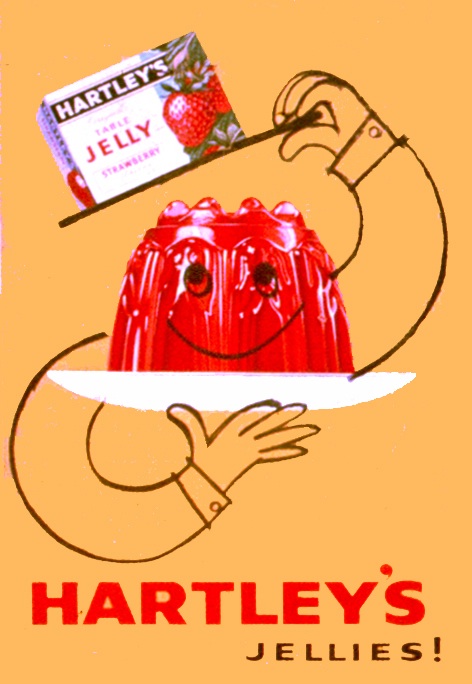

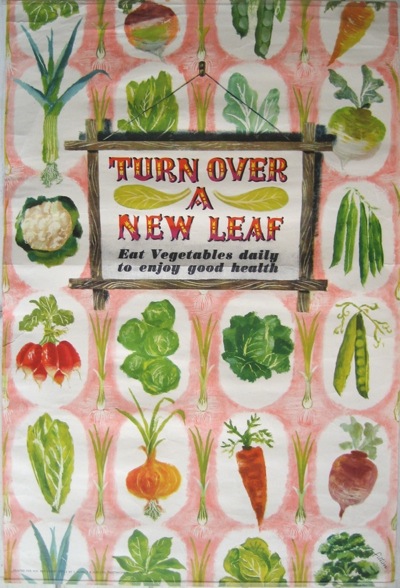

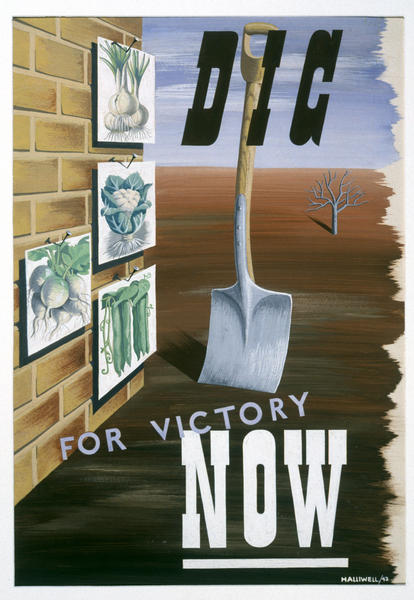

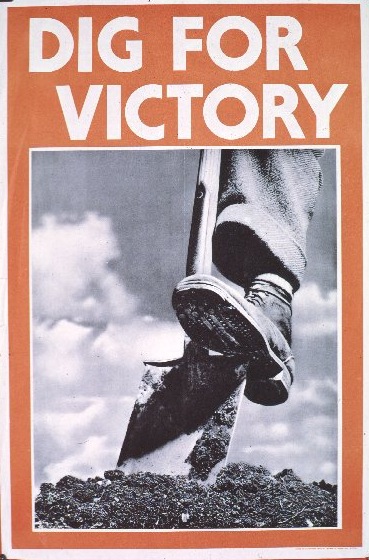

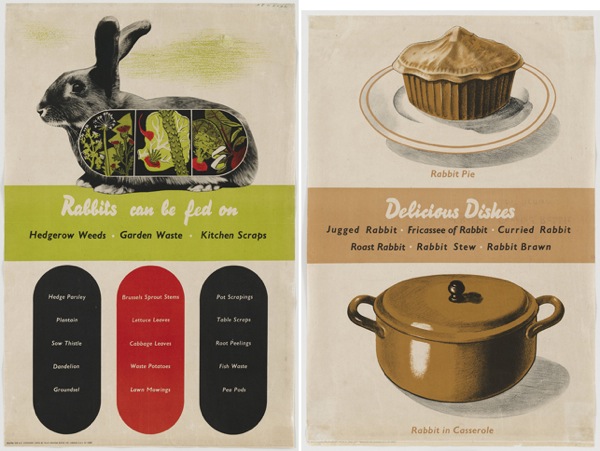

The other really popular category are those about food, and in particular, growing your own. It’s no surprise really that the ‘Dig for Victory’ posters are popular in an era where allotments are over-subscribed and the provenance and Britishness of food is becoming more important.

Their message seems quite clear if we want to read it, that we are too dependent on the supermarkets, we don’t know where our food comes from, that self-sufficency has to be a good thing.

But there’s also a deeper undertow at work here. One of the cores of Britishness is an identification with the land and the countryside (see David Matless and Patrick Wright

and Patrick Wright if you want to read some much deeper thinking than mine on the subject). So there is also a fear that as we become more urban, more detatched from the land and its produce that we are losing sight of our essential selves. If we all had a spade and a piece of soil, might we also be better Britons too?

if you want to read some much deeper thinking than mine on the subject). So there is also a fear that as we become more urban, more detatched from the land and its produce that we are losing sight of our essential selves. If we all had a spade and a piece of soil, might we also be better Britons too?

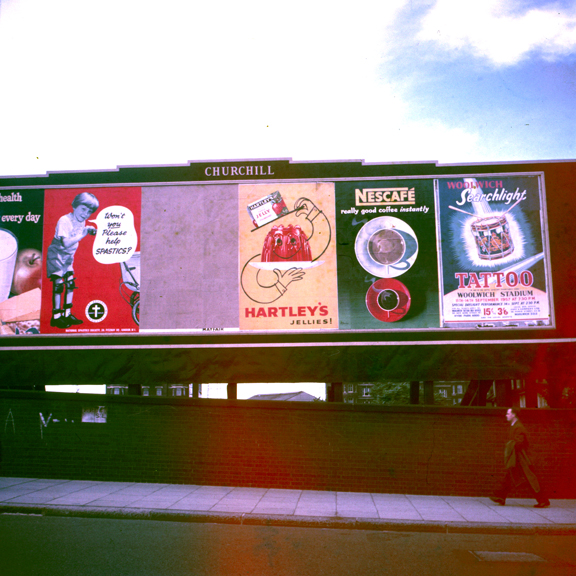

At this point you may be thinking, yes, well, this is all fine and good but isn’t it reading just a bit much into some old posters which people like because they are pretty and cheerful? Another way of making the point, though, is to look for the absences, the posters that we don’t tend to look at and remember.

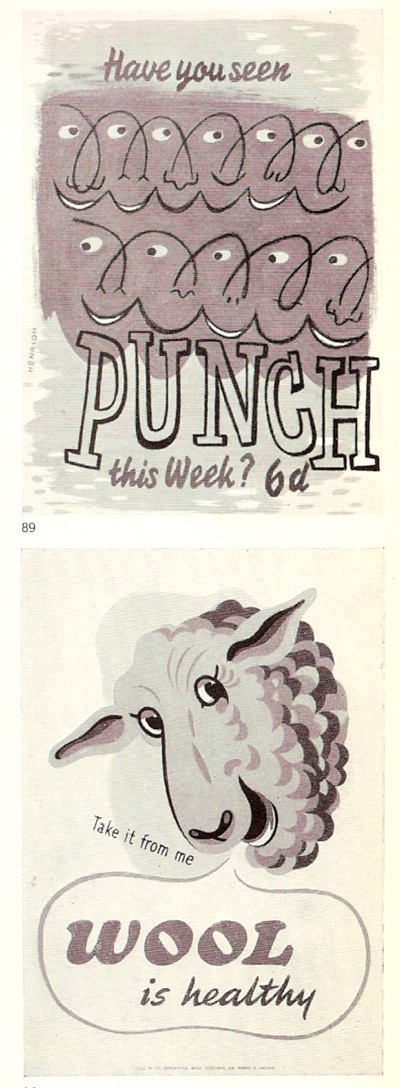

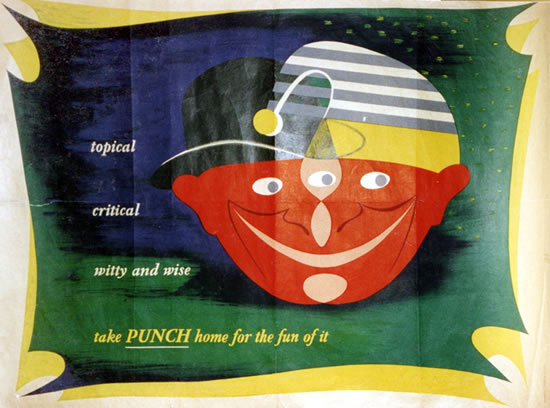

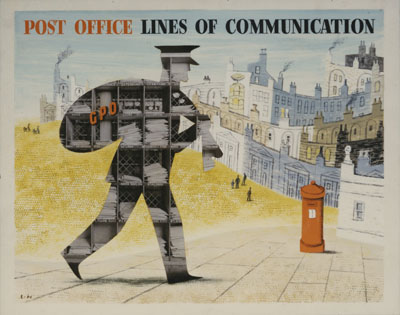

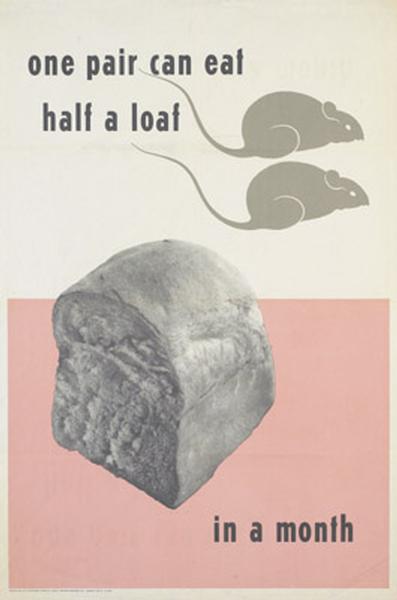

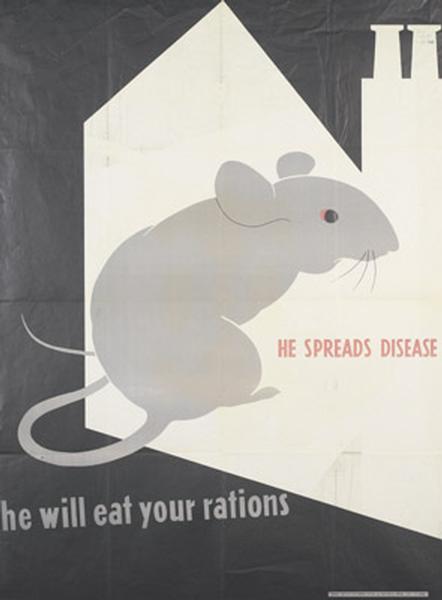

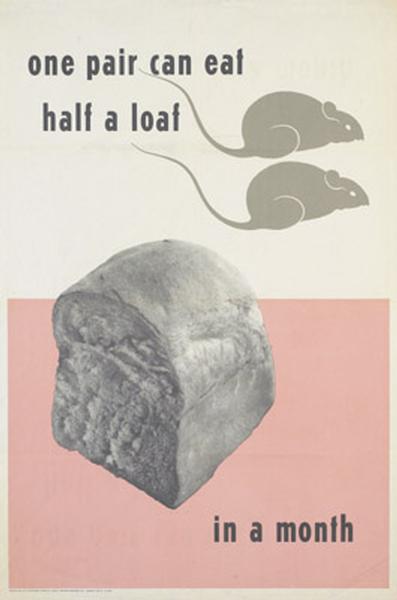

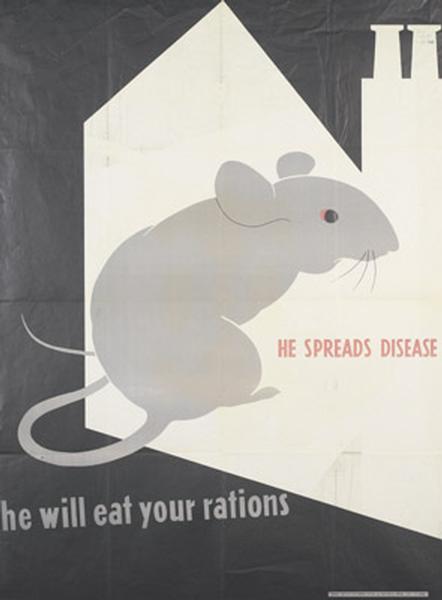

A fascinating example of this came with the MoMA exhibition about kitchens earlier this year, which included a set of British Home Front posters by Henrion and the mysterious Herbert Tomlinson. They don’t tend to get reproduced much in this country, even though they are on the perennially popular subject of food.

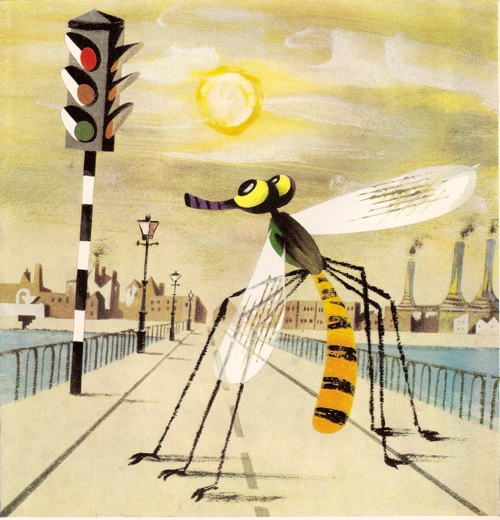

MoMA has as its founding principle a wholly other myth, which is the inescapable rise and total superiority of International Modernism. These posters (unlike the vast majority of Britain’s wartime output) fit into that very nicely, so the museum has collected and displayed them. Over on the other side of the Atlantic, though, this is not how we want to remember the war, as a grubby fight against vermin in bomb-damaged homes.

And we certainly don’t even want to think about eating rabbits which have, in the last seventy years, almost completely made the journey from food group to pet. So we have edited them out of the collective record (despite the fact that these are all in the IWM collections too).

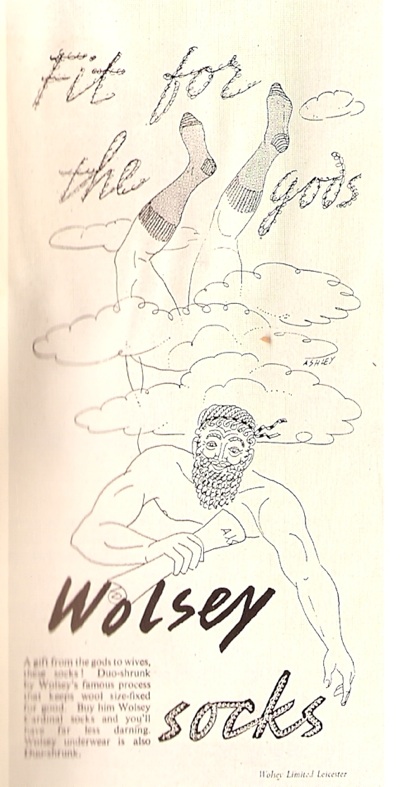

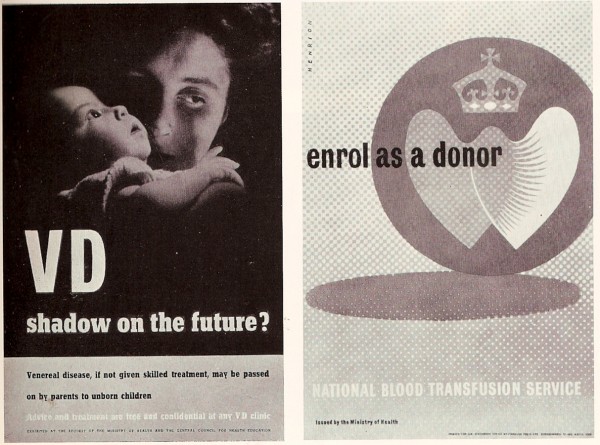

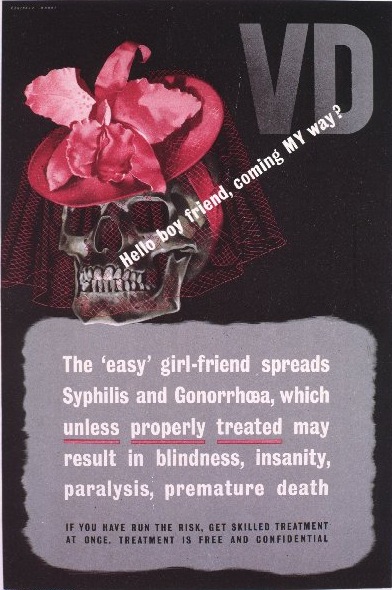

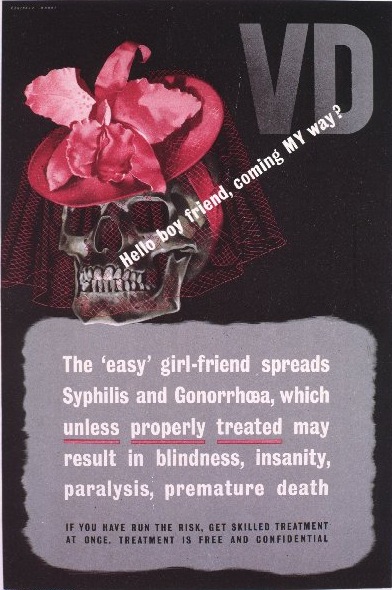

The same might be said about posters informing people about VD. This design by Reginald Mount is a design classic, but that still doesn’t mean you’re likely to see it republished very much.

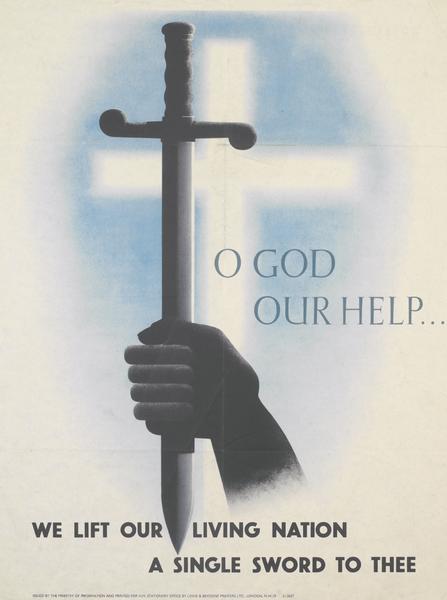

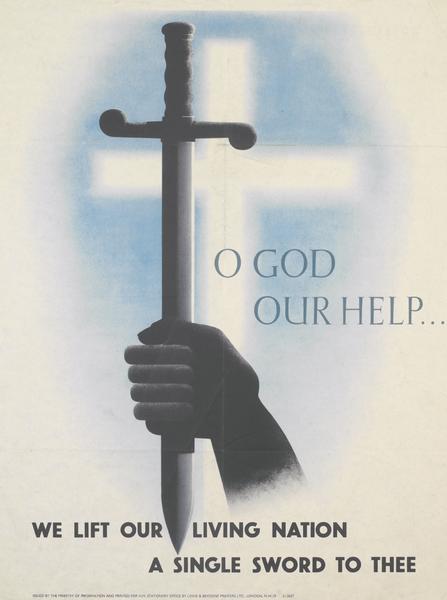

Nor, indeed, this one, for slightly more complicated reasons. The lines are from G.K. Chesterton, the sentiment almost impossible to imagine nowadays.

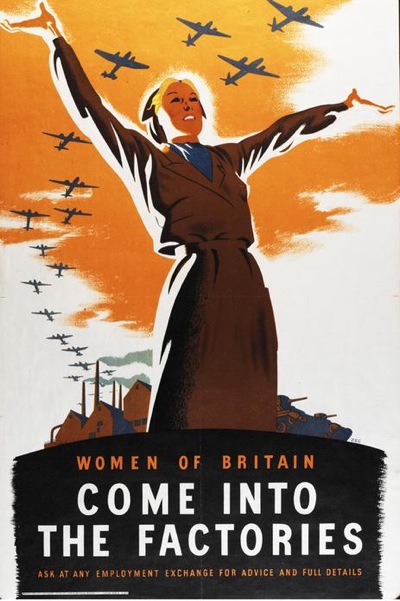

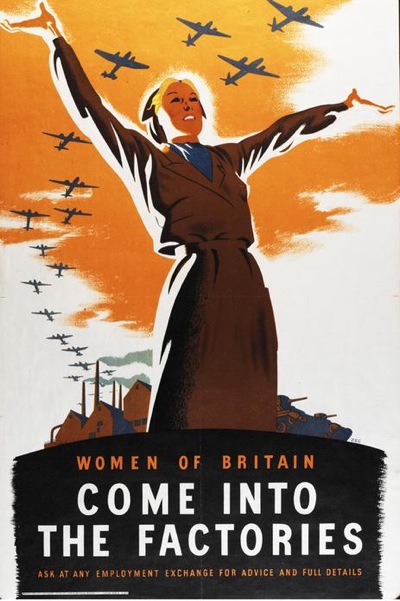

A more subtle example is provided by this Zec poster, which is one of the ones I bought as postcards from the IWM all those years ago.

Then, it was very popular, but this was a time when feminism was more vocal and more active, campaigning for greater workplace equality for women rather than proposing pole-dancing as a form of liberation. So the war could and was represented as a time of emancipation for women when they could do any job they chose, including the dirty factory ones. Nowadays we believe, whether it is true or not, that this particular battle is over and women can do whatever they want; there is no anxiety there any more so we no longer need the poster to express our thoughts and it has sunk below the horizon once more. Its Sovietesque stylings may also have been its undoing too, now that there is little of the heroic to be found in Communism any more, not even for students.

Sometimes the myth requires that we ignore the evidence which is in front of our eyes. One of the reasons that we want to remember the Home Front is the sense of collective effort, the idea that every single person’s attempts to salvage or save or grow some greens made a difference to the common cause. It’s a satisfying idea, and not a belief which is easy to have today.

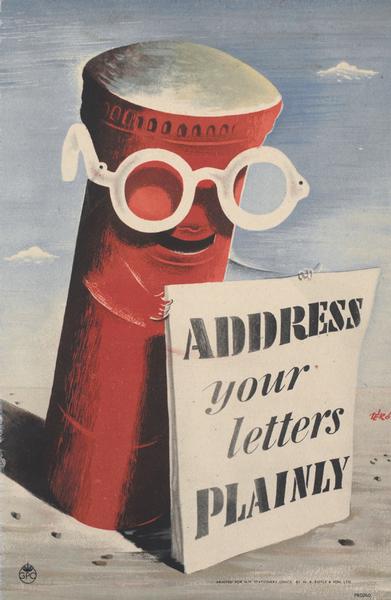

But at the time, the British self-image was very much one of individualism, in clear contrast to Germany, where the individual was subsumed into the masses of the Nazi state. So if you look at these, and indeed almost any World War Two poster, what you will find time and again is a single person (or indeed elephant) doing their bit out of choice, not as part of a mass movement.

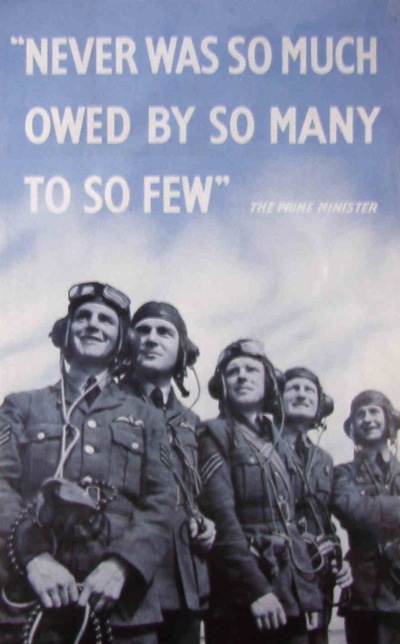

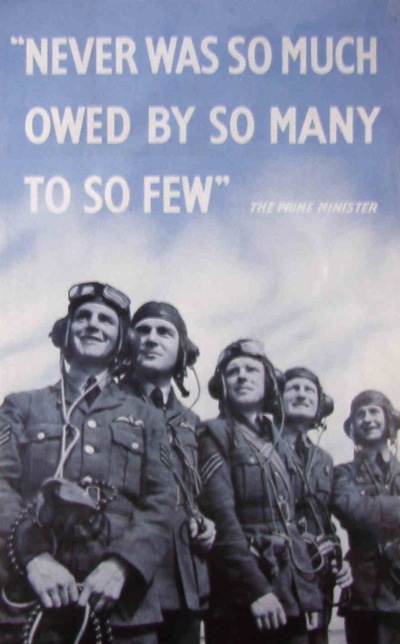

Even in the case of the forces, where you might think that it was good to show that we did have plenty of man-power, the image is much more likely to be of a single ship than a whole marching platoon of men. The poster below is perhaps one of the more populated ones that British propaganda ever produced.

But even then, the men are not only clearly represented as individual people, but also characterised as ‘The Few’. However much we like the idea of the wartime social spirit, we’re never really going to find it in the posters.

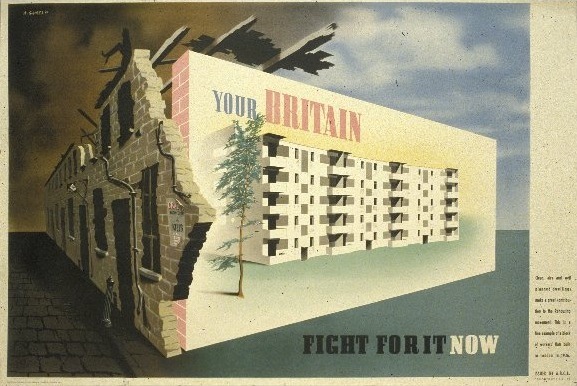

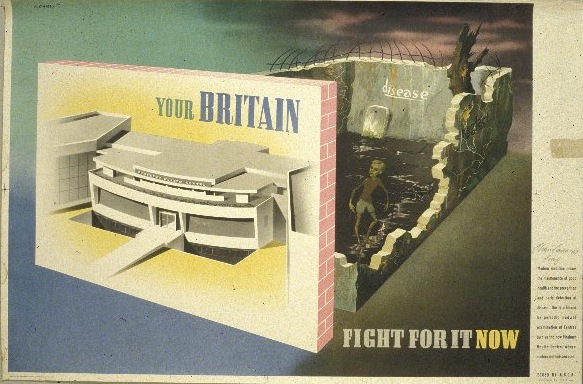

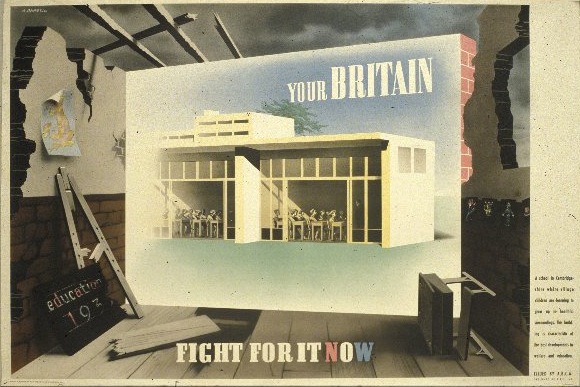

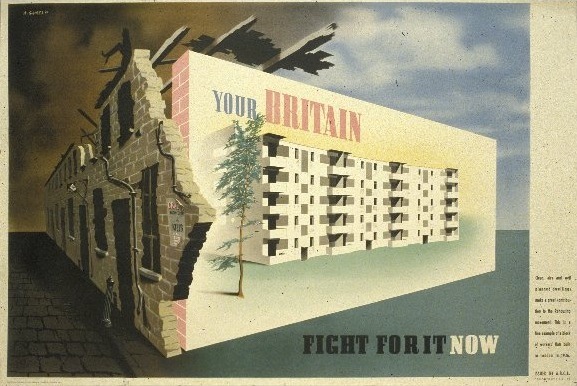

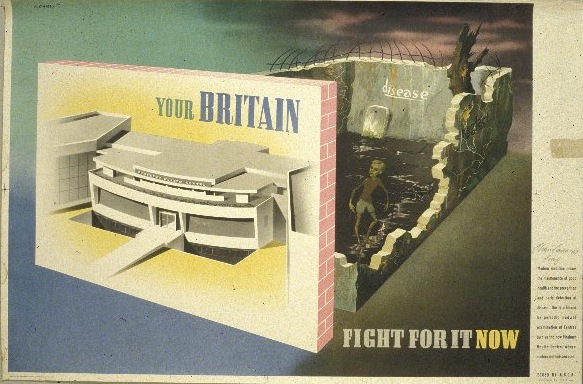

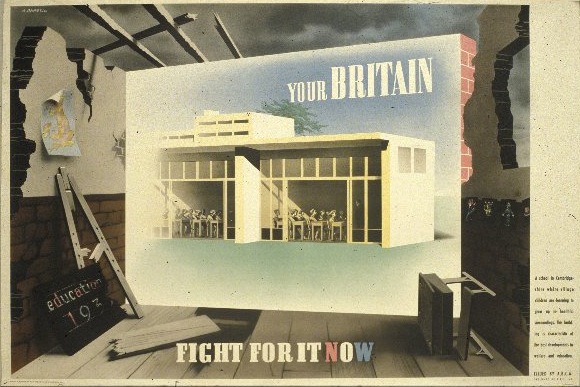

A more complex example are the set of posters by Abram Games imagining post-war life in comparison with what had come before. They are (and I will come back to this aspect of Games’ work during the war another day) quite exceptional, in that generally British posters and propaganda avoided considering the world after the war had ended.

The poster of Finsbury Health Centre below is particularly famous, mostly because Churchill very much took against it. He ordered the poster to be suppressed, complaining that it was a ‘disgraceful libel on the conditions prevailing in Great Britain before the war’.

It could be argued that it was the controversy which made the poster’s mark on history. But other poster controversies during the war ended up forgotten; these posters are remembered because they have important resonances as well. For a long time World War Two has been seen as the crucible which dissolved class consciousness and lessened ingrained inequalities, an achievement which was an essential part of the myth. For Calder, this was one of its redeeming qualities.

…at least the Myth had fostered the notion of the mutual responsibility of all for the welfare of all.

But there are not many posters which reflected this ideal, so the few which do are particularly valuable.

Or at least they were. We live in a time when many of the egalitarian achievements of the post-war reconstruction – universally available higher education, council housing, a moral investment in state education and social care – are being undone, will these posters in their turn disappear from view? I hope not. Now more than ever we need the reminders that these values are still very much worth striving for.

(Almost all the images are from the Imperial War Museum collections on VADS).