Category: Uncategorized

Door thirteen

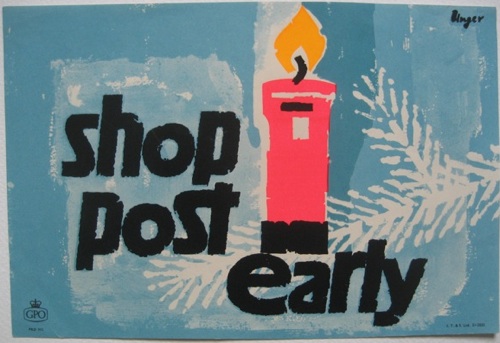

Oh I do love this poster.

It’s by Lewitt Him and was issued in 1948.

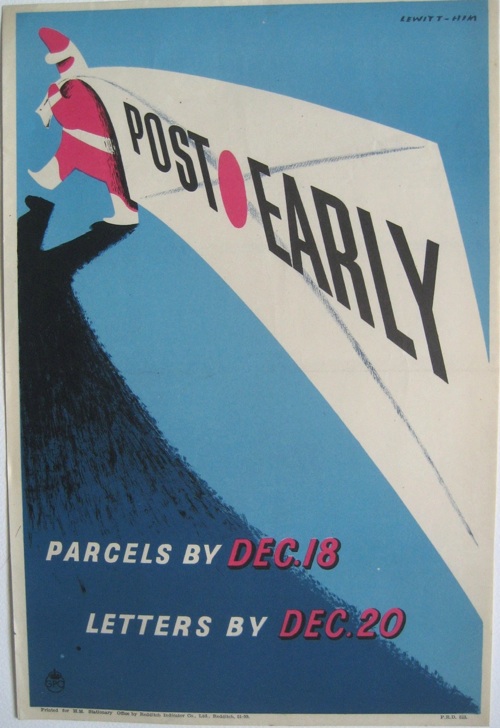

Now I always associate it in my head with this design of theirs (to the extent that I am continually surprised to find out that we don’t just have the same poster in two different sizes).

But this is a wartime one, from 1941, and has nothing at all to do with Christmas. It’s not just the twin outsized letters, I think it’s also the matching red dots of sealing wax that confuse me too. It’s a bit unfair really, because they’re not really recycling the design that much. I’m just easily confused, especially this time of year. They are both still brilliant, though.

Door 3

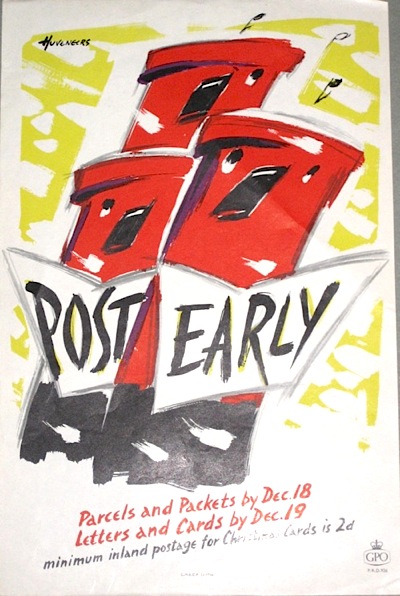

Another miniature today, but this time it’s singing postboxes. Obviously.

They’re the work of Pieter Huveneers in 1957. They also exist in portrait format (below) but I think I prefer these ones. Does anyone know where these small format posters were displayed?

Maybe four is a jollier number for carol singers.

(Apologies for the quality of some of the photographs by the way – they were only ever meant as reference shots for us, well before Quad Royal was ever thought of, never mind an advent calendar. I am going to go and reshoot some of the worst offenders when I get a moment.)

Further training

I’m really glad we don’t collect railway posters very seriously. Because we’d be stony broke by now. This year has just been sale after sale of high quality railway posters (with a fair slew of London Transport stuff too). And now, to round off the year, there’s another one.

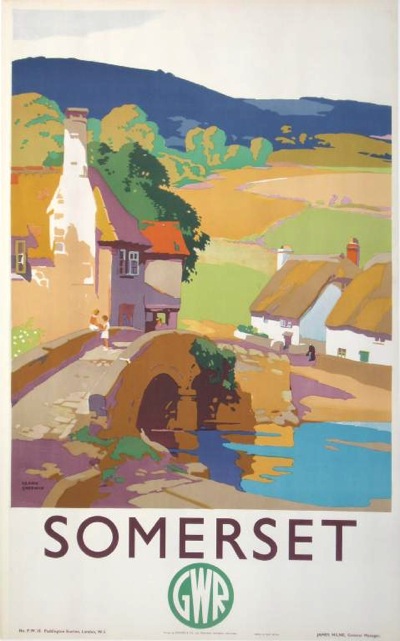

Onslows’s December sale titles itself Vintage Travel Posters including Fine British Railway Posters. Which means posters like this, by the dozen.

Frank Sherwin, 1930, est. £800-1,200

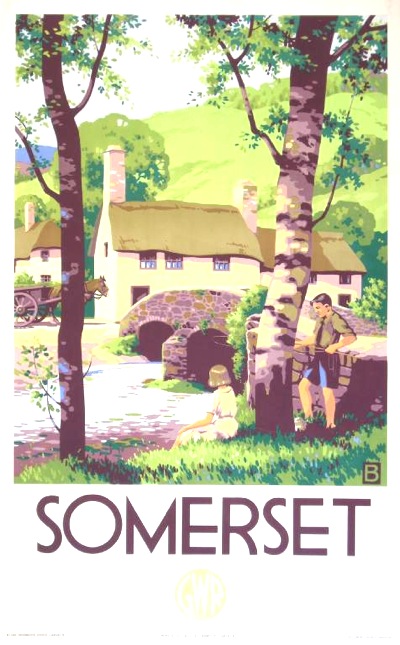

And this. Which is quite interesting, because it’s by Brian Batsford, of book cover fame.

Brian Batsford, 1930, est. £800-1,200

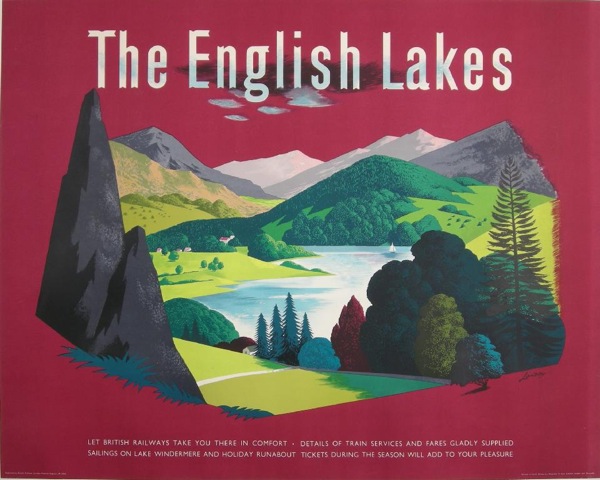

Although there is also this too, which, as I think I have mentioned before, every right-thinking home should have a copy of.

Eric Lander, est. £700-1,000

Plus there’s lots of pictures of trains too, but I shan’t be bothering you with those today, or indeed on any other day. Apparently most of the collection comes from a single estate sale, although I think I can recognise a few things which did also appear at Morphets earlier this year.

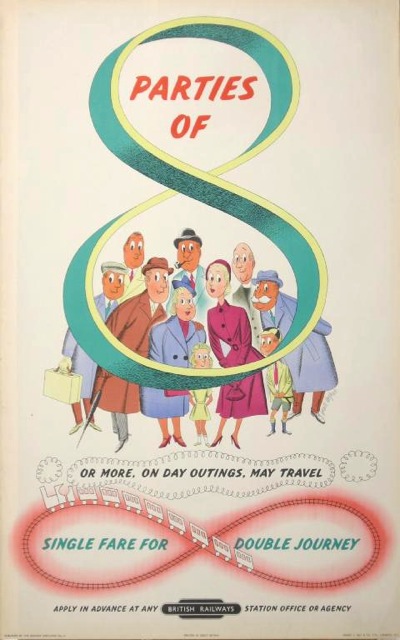

Bruce Angrave, est. £250-300

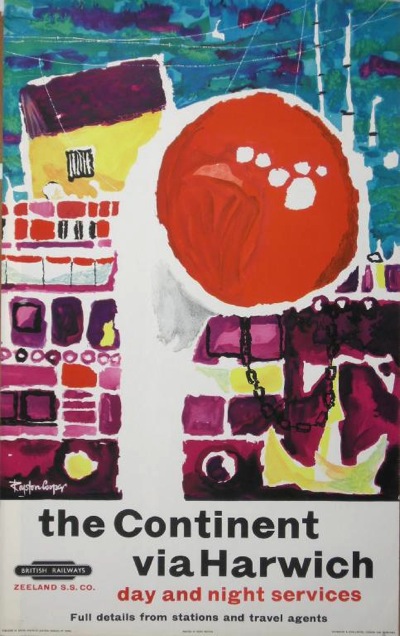

Royston Cooper, 1959, est. £200-300

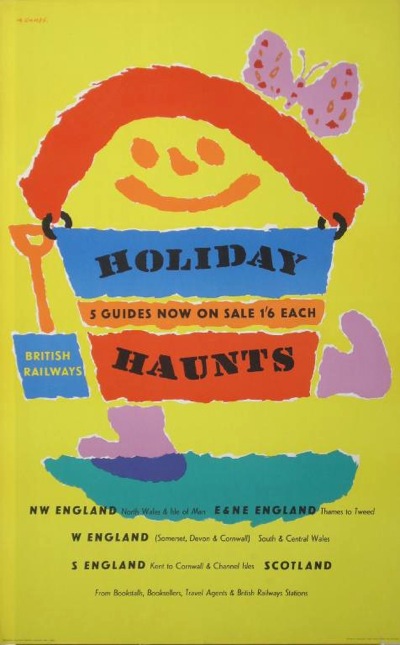

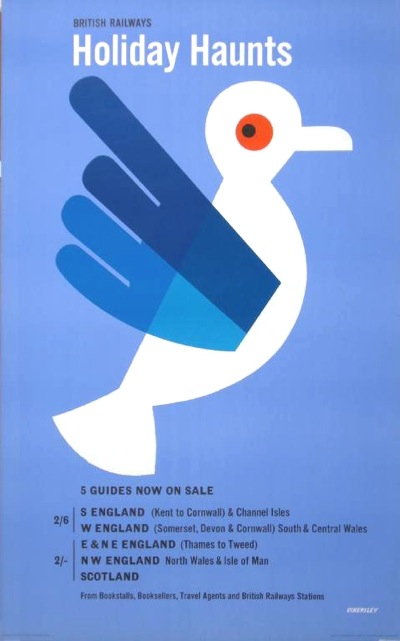

These Holiday Haunts posters by Abram Games and Tom Eckersley also appeared there as a single lot too – the Eckersley in particular is a fine thing.

Abram Games, 1960, est. £200-300

Tom Eckersley, 1962, est. £200-300

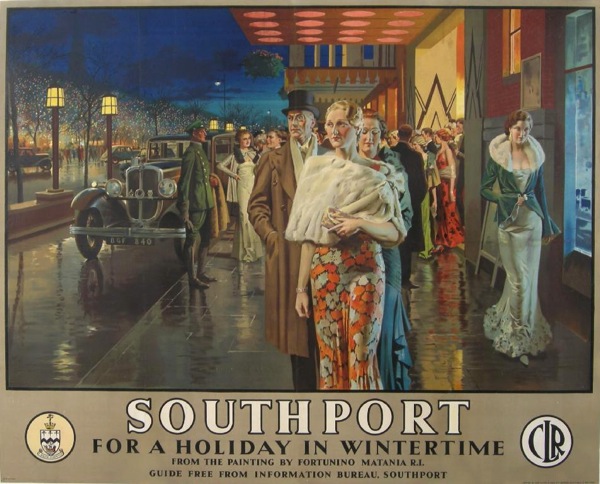

Elsewhere, it’s the usual Onslow’s miscellany. This poster seems to appear in almost every single sale they do, which at the price it goes for is quite an achievement.

Fortunino Matania, 1933, est. £6,000-8,000

This is the rarer version, apparently, because it’s overprinted with the logo of the Cheshire Lines Railway rather than the LMS. I have to say that I can’t quite bring myself to be bothered about the difference.

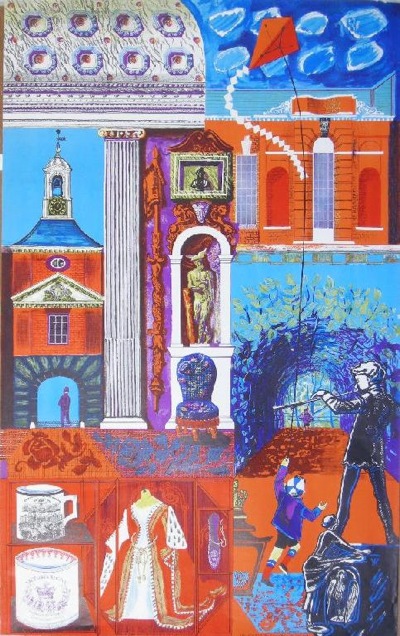

There’s also the usual selection of London Transport posters. I love this Sheila Robinson (which comes with four other posters, it’s all the rage these days).

Sheila Robinson, 1953, est. £200-300.

We once owned a LT poster by her and sold it. I still don’t know what was going through our minds at that point, and now every time I see one of her designs I am filled with remorse.

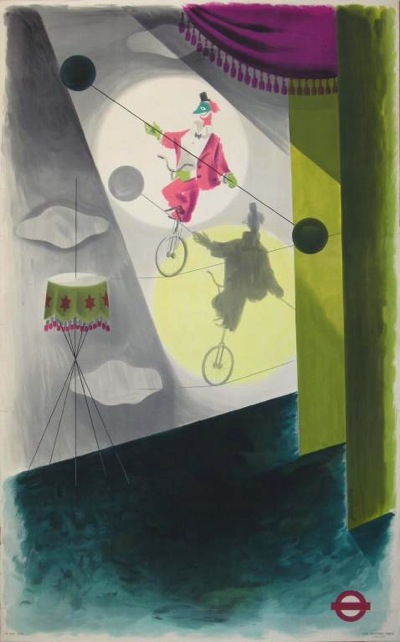

These James Fittons are also rather good too.

James Fitton, 1936, est. £400-600

James Fitton, 1937, est £200-300.

There’s also a complete set of four of these Austin Coopers, one of which featured in the last Christies.

Austin Cooper, 1933, est. £1,000-1,500

Although at that kind of estimate, a set of four is going to be a pretty substantial investment.

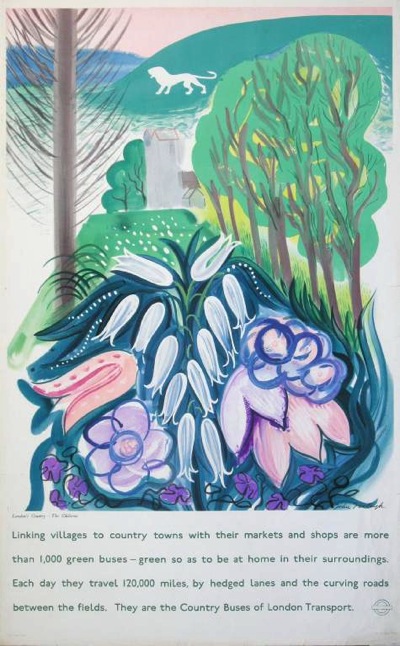

I also rather like this. And it’s a lot cheaper too.

John Farleigh, 1947, est. £200-300.

But then I am always a sucker for a chalk hillside figure.

There is still more to consider in there, but I’ve run out of time. So, World War Two posters and other miscellaneous bits and bobs next week. And an Advent calendar too.

You, the jury

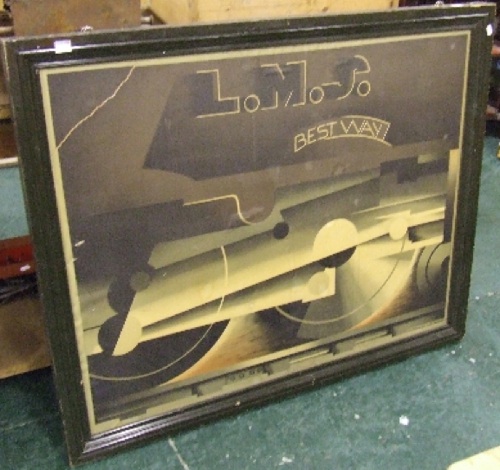

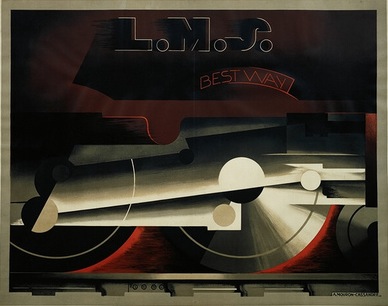

A quick question today. Which basically boils down to this: real or not?

And there’s quite a lot riding on the answer, because this is up for auction at Brown & Co in Lincolnshire with an estimate of £100-150. Which would be a bit of a bargain, for what might be a Cassandre which is in the collection of M0Ma in New York.

But is it the real deal? I don’t know. The colours are off, to start with.

And the dimensions are too – the auction version is 43″ x 33″, instead of the 40″ x 50″ it probably should be.

Plus the description says that it’s “doublesided” (although how they can tell when it is also framed, I am not sure).

So, I’m unsure enough not to have a go, and to throw it open to you lot to see what you think. Any thoughts, or tips, or opinions out there?

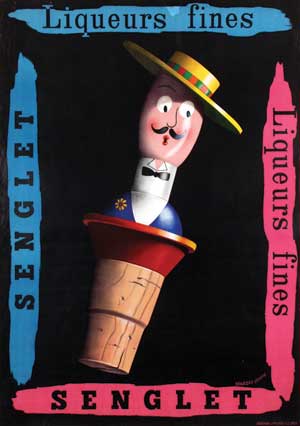

Mind you, even if it is a cropped reproduction, it’s probably still worth more than the estimate. Chisholm Larsson are selling this.

It’s a 1980s reprint, but they want $750 for it anyway. It’s a mad world, Mr Benjamin.

Distinction

I have on my desk two books, a thick one and a thin one. The thin one is Melanie Horton’s book on the Empire Marketing Board Posters at Manchester University. But, rather counter-intuitively for a Friday, I’m going to go for the doorstop sized one instead, which is Distinction

by Pierre Bourdieu.

It has been, I discovered today, voted one of the most influential sociological books of the 20th Century. Wikipedia can summarise it, as they do this rather well.

Bourdieu discussed how those in power define aesthetic concepts such as “taste”. Using research, he shows how social class tends to determine a person’s likes and interests, and how distinctions based on social class get reinforced in daily life.

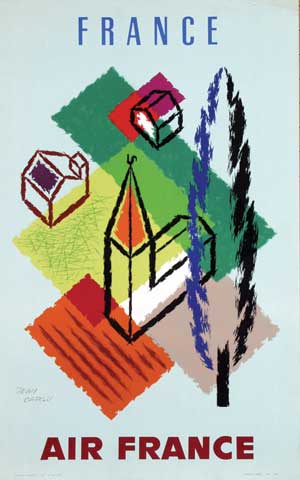

Jean Carlu, 1958

He does this by micro-analysing the taste and cultural choices (whether that’s music or interior design) of a vast number of French families and people in the early 1960s, over 500 pages and with myriad tables, diagrams and interviews.

I was forced to read it as part of my Design History course. But I’m actually rather glad I did. Because although the book is undoubtedly ‘very French’ (as the translator’s foreword warns) his approach is also a very useful way of thinking about design. It earns its keep simply by reminding us that there is no such thing as pure good design or taste, that everything we choose, or turn away from, is a determined by class and culture as well as our own personal preferences.

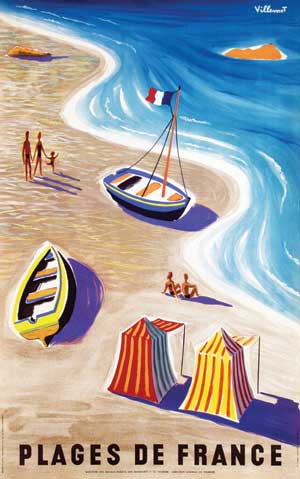

Bernard Villemot, 1955

That’s not the only reason why I’m writing about it here, though. The book may also answer the question, why do I (why do we?) collect posters? I will try to distill the argument from his rather dense and sociological prose to see if it stands up.

One of his key ideas is that the ruling classes don’t just have economic capital but also social and cultural capital. While the first two can be acquired, cultural capital tends to be inherited. And he argues that it is perhaps the most important means by which social classes differentiate themselves. (For example, if you have economic capital, but no cultural capital, you will tend to be pigeonholed as nouveau riche).

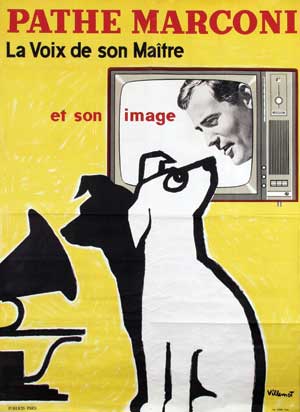

Paul Colin, 1945

But what’s great about the book is that he microanalyses these ideas and how they work in real life. So, he points out that while many people agree on the cultural capital of appreciating art, there is a big difference between the middle classes who go to see it in a museum, and the very small fraction of the upper classes who own it themselves.

The appropriation of symbolic objects with a material existence, such as paintings, raises the distinctive force of ownership to the second power and reduces purely symbolic appropriation to the inferior status of a symbolic substitute.

Roughly translated, too many people are able to ‘appreciate’ a Leonardo da Vinci painting for it to be exclusive enough. But if I own a Leonardo, I can lord it over you and feel superior, because you may only go and see in in a museum. In visiting a museum, you’re trying to reproduce the experience of owning it, but you know that this isn’t as good. I think that’s probably as true of the English upper classes than the French. After all, the English aristocracy let us into their stately homes, so that they can be certain we know that they have lots of nice paintings and we don’t.

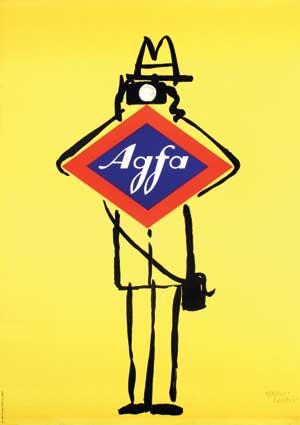

Bernard Villemot, 1960

He also argues that art objects are particularly key examples of the way the upper classes distinguish themselves, because while they take a long time to know about and appreciate properly, they are, in the end, pointless.

[I could type that bit out but it’s fairly headache-inducing, let me know if you want to see it, it’s on p281 of my edition.]

Nonethless, the upper classes don’t get it all their own way. These views can be challenged or subverted. And the people who are most likely to do it, are those with plenty of cultural capital but less material capital. Plenty of good taste, but no money. The problem – as Bourdieu sees it – is that these people like ‘good’ art but can’t buy it.

But in the absence of the conditions of material possession, the pursuit of exclusiveness has to be content with developing a unique mode of appropriation.

The trick is to find ways round this, either by liking things differently or – and can you see where this is going – liking different things.

Intellectuals and artists have a special prediliction for the most risky, but also most profitable strategies of distinction, those which consist in asserting the power, which is peculiarly theirs, to constitute insignificant objects as works of art.

So if I can’t afford a Picasso, I’m damn well going to go and define something else as a work of art. And then own it.

Herbert Leupin, 1956

Now, Bourdieu wrote the book in 1962, and I would argue that there are more people than just intellectuals and artists playing this game now. More and more people have no choice. Fine art prices have risen so much that only oligarchs can think of buying the real thing these days. Yes you could go down the Walter Benjamin route and buy yourself a print – and plenty of people do. But not everyone wants to do that, for whatever reasons. (In my own case, Bourdieu would blame the accumulation of cultural capital caused by a spell at art college, with the distinct lack of economic capital caused by the kind of career which results.)

So if we (if you are with me on this) want to buy art, we have to designate something else as art. So how about posters? They are originals, they are limited, they have the patina of age. We can collect them and display them in our homes, we don’t have to go to galleries to see them. We can, in short, be as upper class and tasteful as we like without having to pay a million pounds for the privilege.

Herbert Leupin, 1952

I think that there are a few peculiarly British twists to the story, though. One is the way that the left-minded section of English upper-middle classes have always rather enjoyed defining themselves against the aristocracy, and so have repeatedly embraced modernism as deliberate snub to posh people’s gilding and decoration (the Herbivore tendency of the Festival of Britain is a classic example of this kind of person in operation). The other is the simple fact that the British tend to have a very small aristocracy (compared to the French bourgeoisie) and a huge, squeezed middle class that can’t afford a grand house and a Van Dyck and there have always been a lot of people who to find another way round good taste.

If that’s fascinated you and you’d like to read the whole darn thing, well you can, here, thanks to the wonders of the internet. Don’t all rush at once.

Next week, Empire Marketing board posters from the pleasingly thin book, and, so help me, even more posters for sale.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering about the images, not only are they all very French, but they’re also all for sale at the next Van Sabben poster auction on December 11th so you can buy them too. If you’ve got the material capital to afford them.