I’ve been meaning for a while to do a series of posts looking at the different archives that sit out there on the web, just waiting for you to rummage through their files of wonderful vintage posters. These resources have exploded in the last few years, and it’s now easy to find out incredible amounts about the history of posters without ever leaving your chair – the kind of research that would have taken years and many many train journeys in the past, even had it been possible at all. So, while the archives may not be making me fitter, I am certainly now both better off, and considerably more informed than I would otherwise have been. Hurrah for the internet.

My thoughts were that I’d start with one of the straightforwardly brilliant ones, like the London Transport Museum catalogue – a complete itemisation of every poster and artwork they own, image-led, designed for users rather than museum curators. But in fact, I find myself wanting to begin with two really quirky ones. So today’s is the BT archive, which until a couple of weeks ago, I didn’t even know existed.

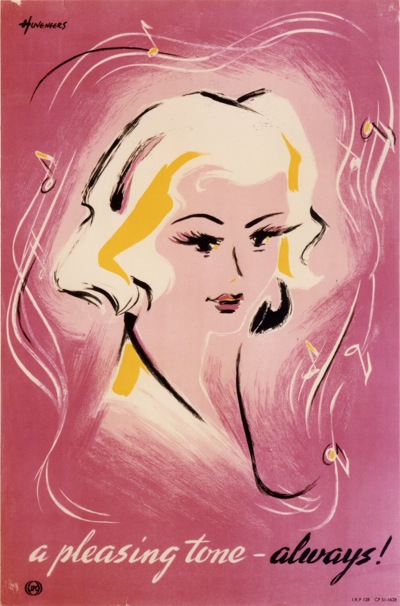

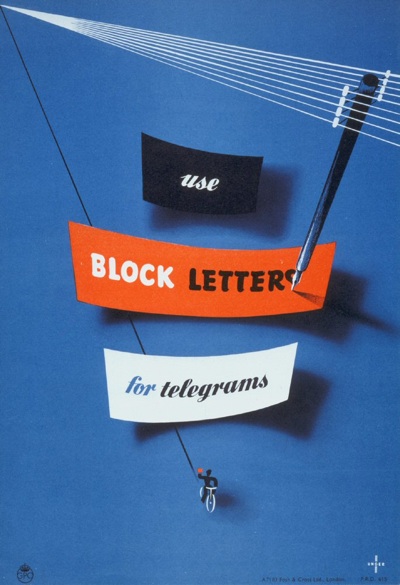

Pieter Huveneers, c1950.

The archivist at the BPMA very kindly pointed me in their direction, because the two collections are separated siblings. When British Telecom was split off from the GPO in 1980, they got the posters about telephones and telegraphs, and the Post Office got the ones about letters. But the artists, the poster sizes and even the cataloguing systems are very much the same.

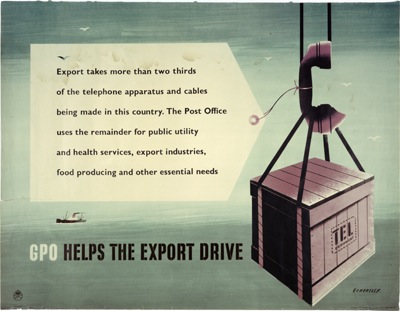

That, sadly, is where the resemblance ends. The BPMA catalogue interface is lovely; it’s reasonably intuitive, I can find what I am looking for with some confidence, and all of the pictorial material is illustrated. The BT catalogue is, if I am entirely honest, a pig. The search logic follows its own rules, there is a wierd link called “ContextRef” which throws up an apparently random list of related material (which then defaults to the search page if you click on anything), and, worst of all, only about 10% of the material is illustrated. What’s particularly annoying about that is that, in researching this, I’ve found a company who claim to have had the contract to digitise the entire BT archives. So where have all these pictures gone then? Although, on the plus side, I did find this 1948 Eckersley on their blog, and I swear I’ve never seen it before (if you have, please do say in the contact box below).

But, as you can see, I have spent rather longer than I intended sifting through page after page of slightly dry records (I don’t, I have to say, like reading catalogue numbers) in search of the few illustrations that do exist. Because the few that are there are wonderful. This wartime Henrion is particularly wierd – I’d like to find out more about him, some of the images are really quite disconcerting.

Although this one, from 1951, is quite benign.

Then, after the best part of an evening reading ContextRef numbers and swearing, I found out how to buck the system. Some, and quite possibly all the images are available through the BT image sales website. Which is organised by picture, and theme, making finding images less of a needle in a haystack hunt.

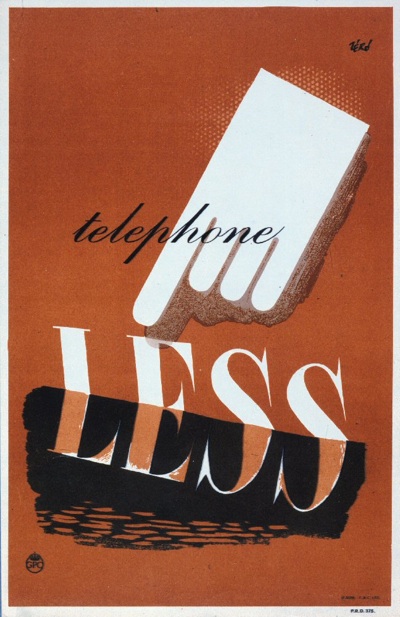

Reiss, 1945

There are disadvantages, like the fact that there are rather more pictures of trimphones and Busby than there are posters, and the images are watermarked.. But it does at least, in the advertising and wartime sections, give you a rough overview of what kind of posters the GPO was producing and whether or not you might want to look at some more.

This isn’t the first time I’ve used the image sales get round; for a long time, the only way to find out what posters the National Railway Museum held was to go via the Science and Society website. The NRM now do have a searchable online catalogue (of a railway buff kind) which is better than the slightly random selection that Science and Society used to dole out. But if you’re searching an archive through image sales (do you hear me V&A as well?) it’s a sign that they could, possibly, do more towards making them available on the web.

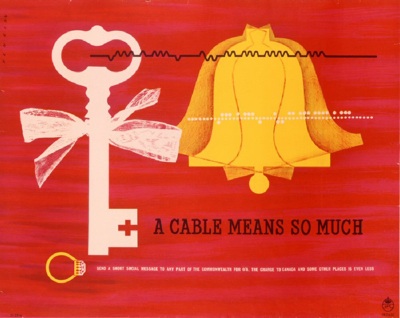

Moan over. So here’s one last nice poster to cheer ourselves up, a faultless Unger from 1951. Pip pip.

Do you know about the Eckersley Archive at LCC?

Well worth a look.

P

Yes thanks, I do – I blogged how much good it has done for Eckersley’s modern reputation here a while ago: