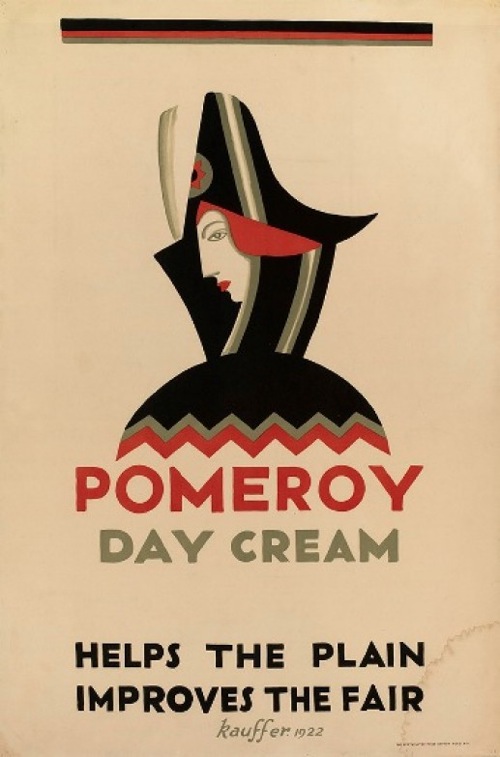

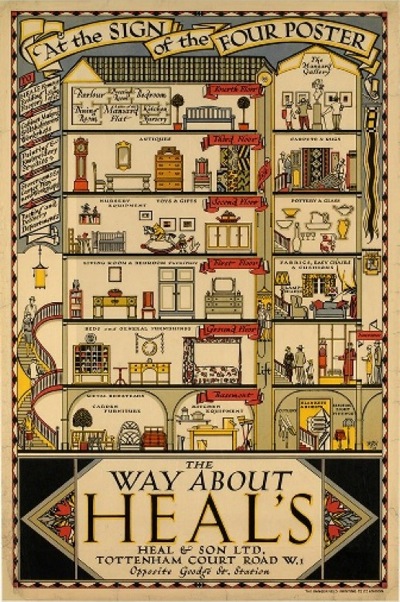

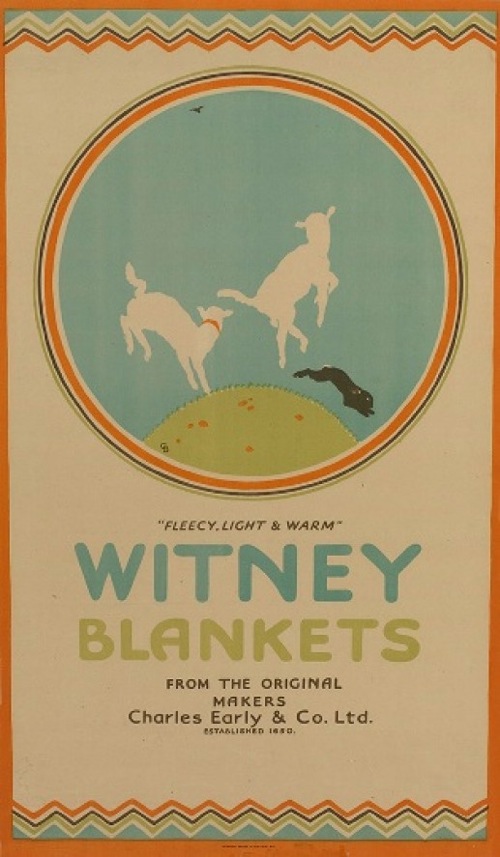

So, finally, after several advance mentions it’s time to have a look at the new V&A book about posters, British Posters: Advertising, Art and Activism .

.

I don’t think that the fact that this has been sitting around on my desk for a week or two is just an accident of circumstances. It took me a while to start reading it, even though I knew I ought to. Every time I picked it up and flicked through it, I wasn’t inspired to carry on. When I’d made myself read it, I then didn’t really know what I wanted to say about it. I’m still not sure whether I like it or not.

To some degree this is as much my fault as the book’s. The title sets out its range quite clearly – art and activist posters as well as the commercial design that I tend to prefer – which means that large swathes of the book are not really my cup of tea. Although I do also think that it could have tried to persuade me a bit harder that these things are worth my time. At the same time the things I am most interested in – commercial posters pre and post war – don’t get enough of a treatment for my tastes.

But let’s accentuate the positive. The book does have some thought-provoking ideas in it. I’ve already mentioned the fact that it sets out a very useful history of outside display. While reference to the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 may sound dry, it actually matters. The decline of the poster during the 1950s can be seen not just as result of the rise of television, but also of the restriction of poster sites. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, local authorities used the act to ‘clear poster sites from rural and residential areas’. There were arguments for the poster as an integral part of the urban scene, but mostly the planners won. Poster sites were no longer huge billboards, but instead decorous display columns in shopping centres. No wonder the power of the poster was on the wane.

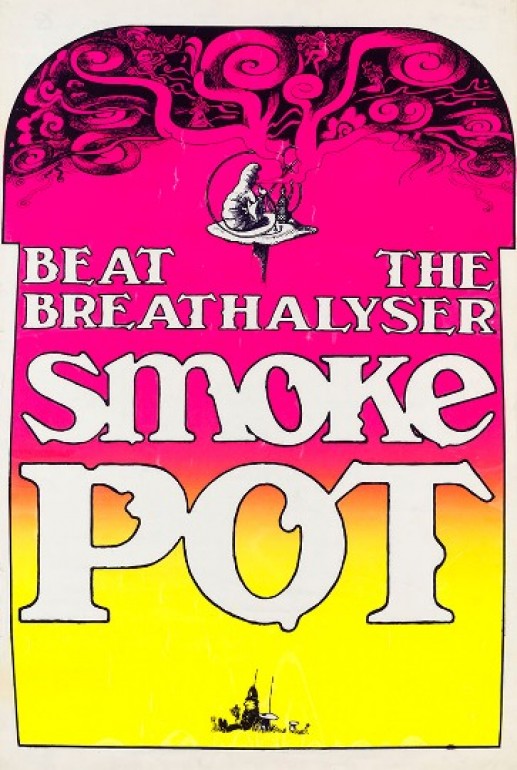

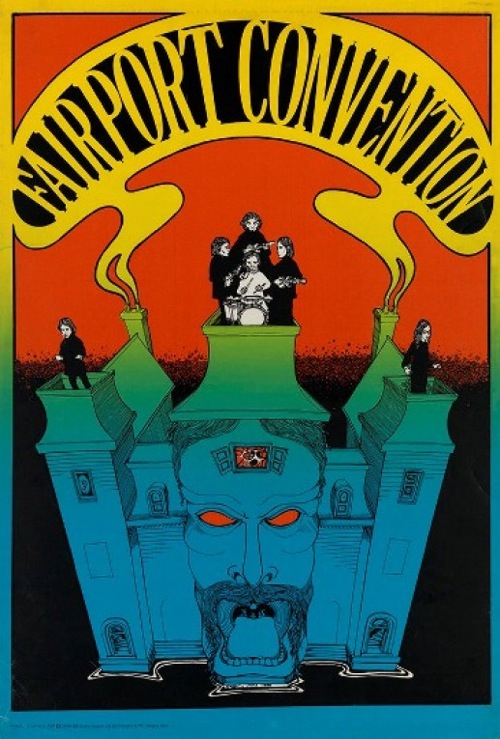

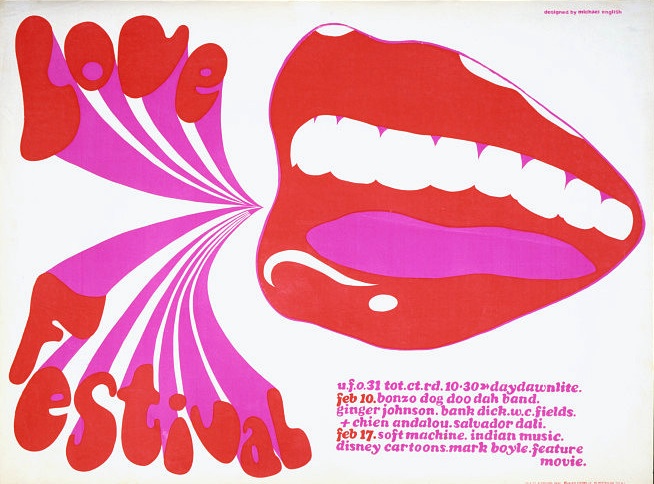

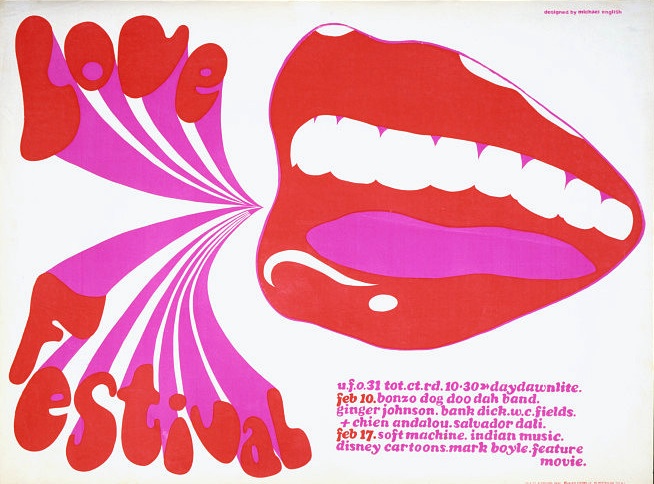

Another one seems blindingly obvious, which is that the meaning of the poster changed significantly between 1950, say, and 1970. No longer did it mean a piece of advertising, instead a poster was something that you bought from Athena to decorate your room (students, this means you). While this is something that we all understand at some level, it’s important to articulate it, as it has all sorts of interesting implications for how we think about posters. So interesting in fact that I’m going to give them a blog post all of their own one of these days.

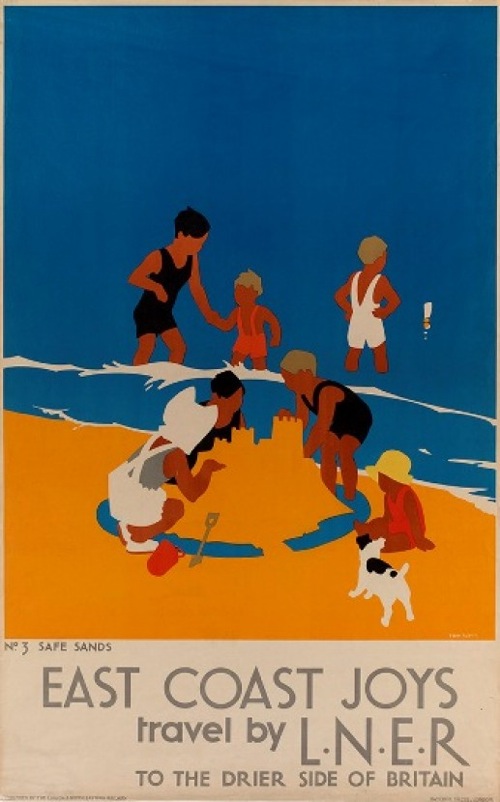

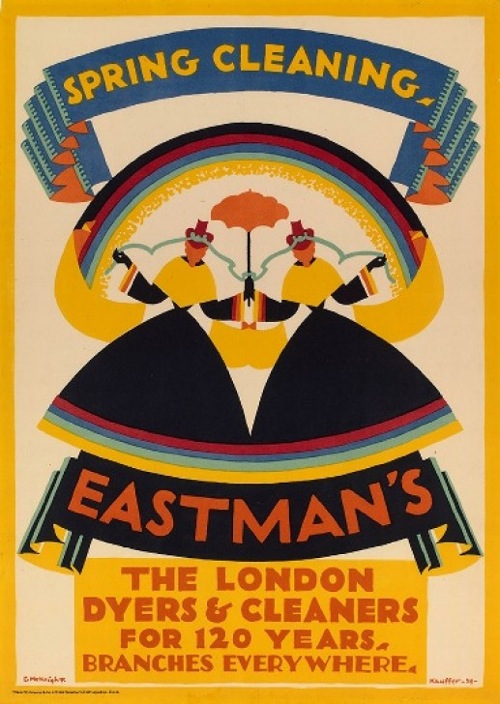

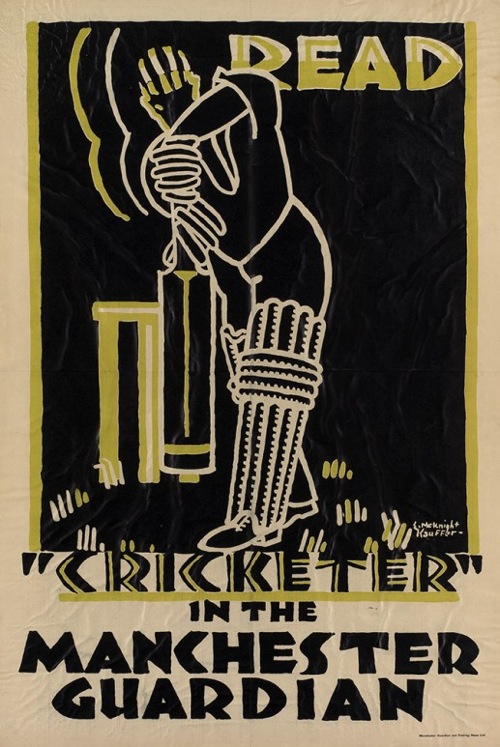

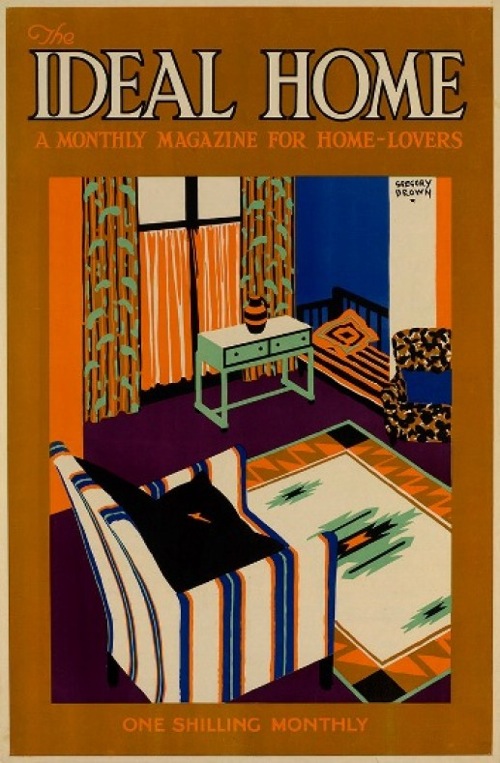

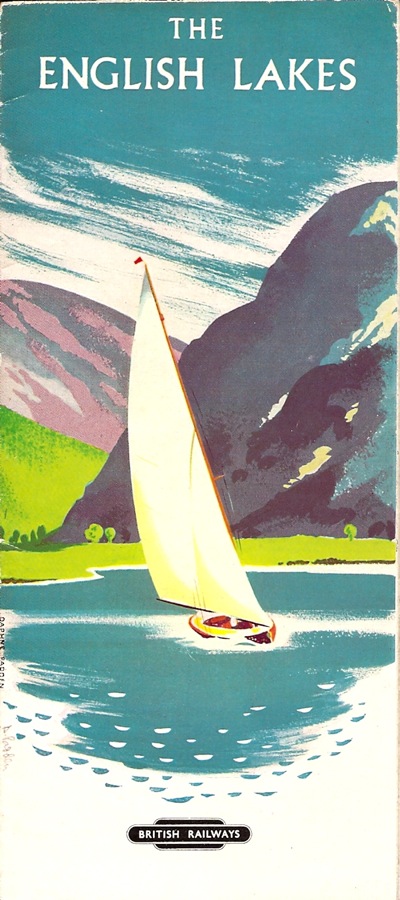

Another thought worth holding on to is the way that posters have, for a whole host of reasons, been singled out from the greater mass of graphic design. Flood ascribes this to the vogue for posters in the late 19th century, which set the habit of collecting, cataloguing and admiring them. I’d also argue that now it is also because they are most like art, in that they are flat pictures which can be framed and hung on the wall. But at the same time they are also very unlike art – I’m thinking here of railway posters in particular which continued the British tradition of landscape art when the vast majority of fine artists had abandoned it entirely. Work that one out then.

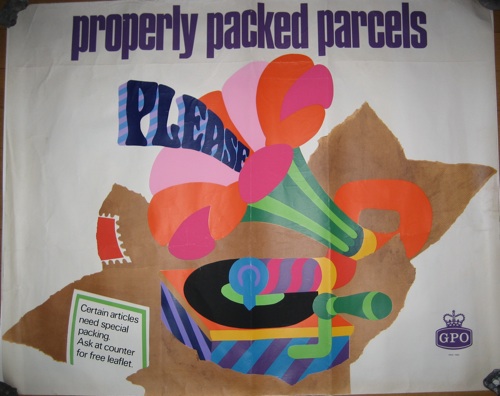

The development of the poster market is also something I’ve never seen considered before either. I was particularly interested in the account of a man named Bob Borzello, who ran a poster import export business from Islington during the 1960s psychedelic boom.

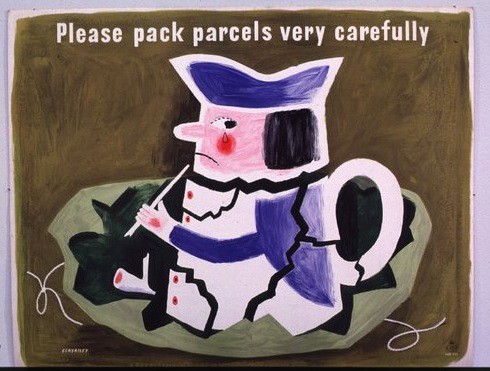

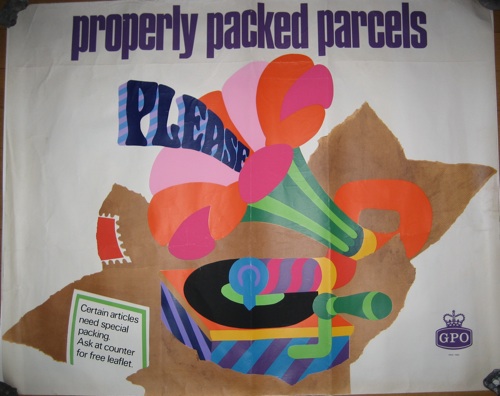

He selected British posters for the American market: posters for theatre companies, London Transport and the General Post Office proved popular, and he claimed he could charge more for anything with London on it.

Where have all these GPO posters gone then? I need to know.

In between these flashes of interest, though, there is a lot which isn’t quite so enthralling. In part this is because this book is trying to cover an awful lot of ground in not that many words, so ends up being very general by default.

There is also the fact that I cannot bring myself to care about 1970s agit-prop posters in the way I care about Tom Eckersley or Barbara Jones. I would guess that the slightly scattergun choice of subjects is a function of the V&As collecting policy. I can see the political reasons why, if you’re a curator at the V&A, there would be a political reason for taking the collections as both a reasonable depiction of a subject and a fait accompli, but for the rest of us on the outside, it makes for a bit of a disjointed read.

Back in the days when I was doing my time in the V&A, their entire depiction of the ceramics of the 1950s consisted of the studio pottery of Bernard Leach, Hans Coper and Lucie Rie. It was all lovely stuff, but I wouldn’t have liked to write a history of 1950s tableware on that basis. They also had failed to collect any mugs at all. It’s all very different now, but museum collections do still have their biases and absences, and it’s perhaps better to address these rather than take a collection as gospel.

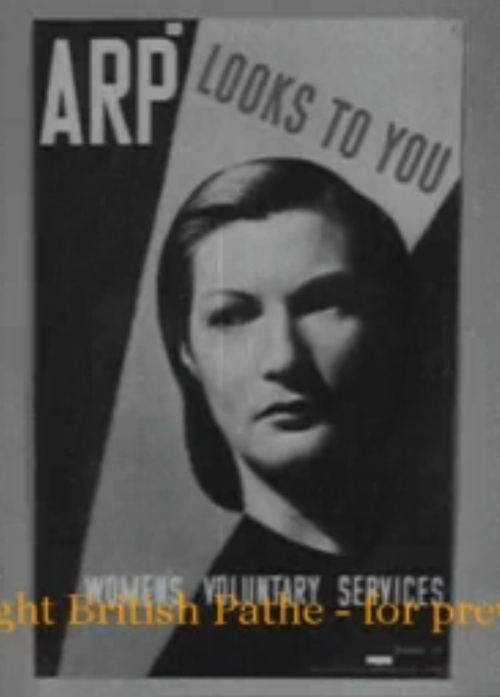

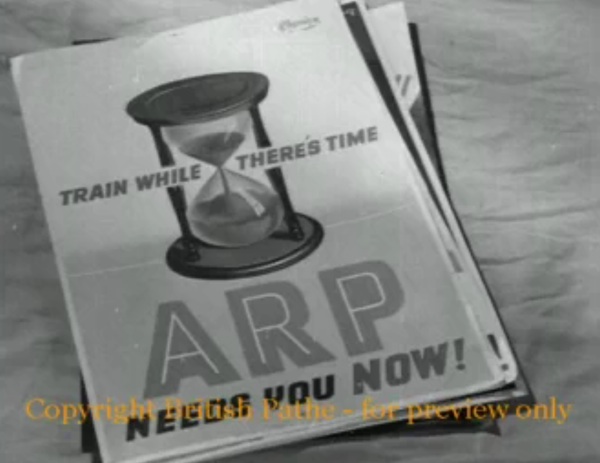

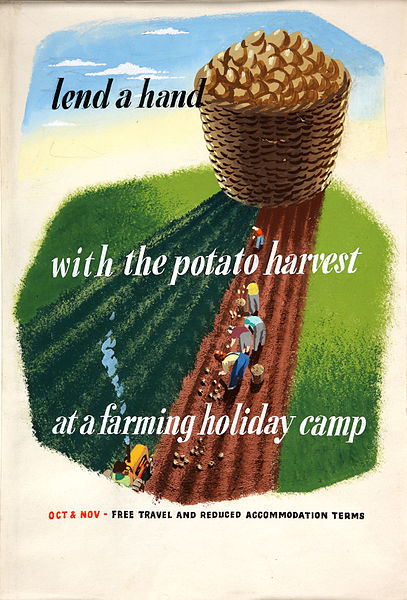

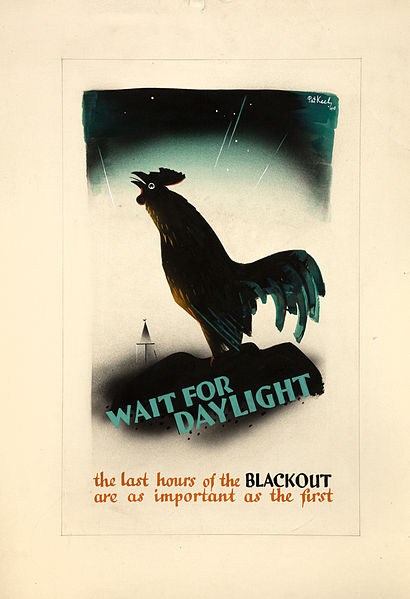

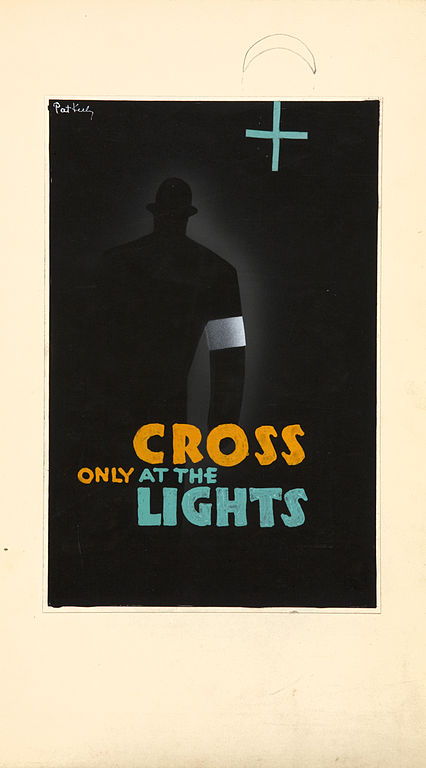

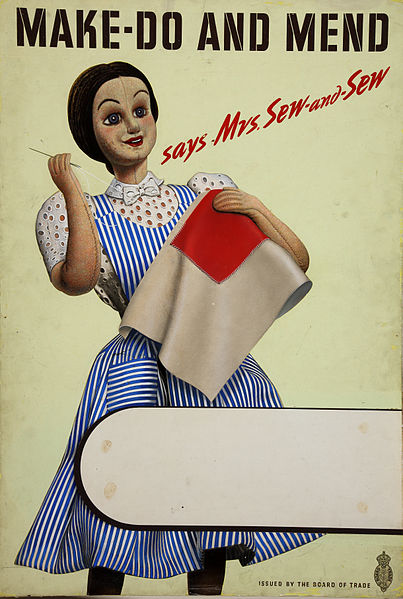

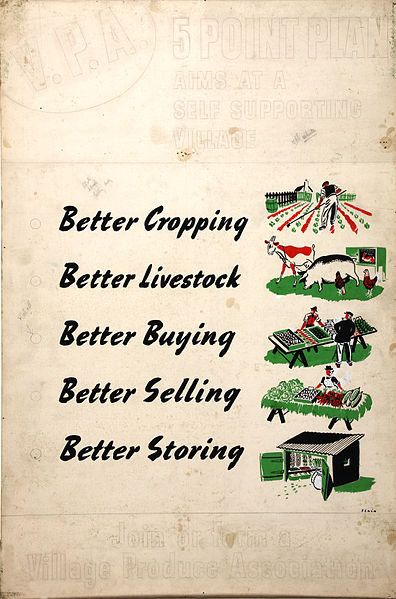

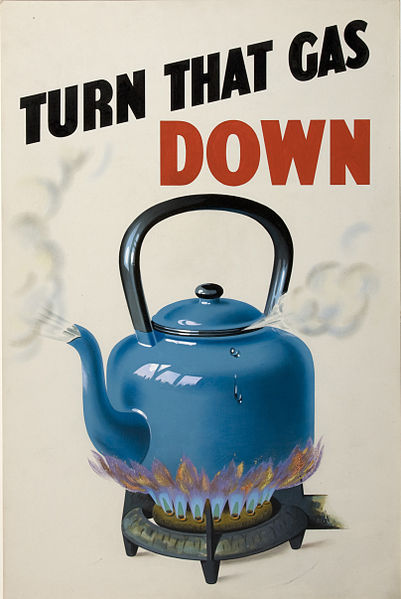

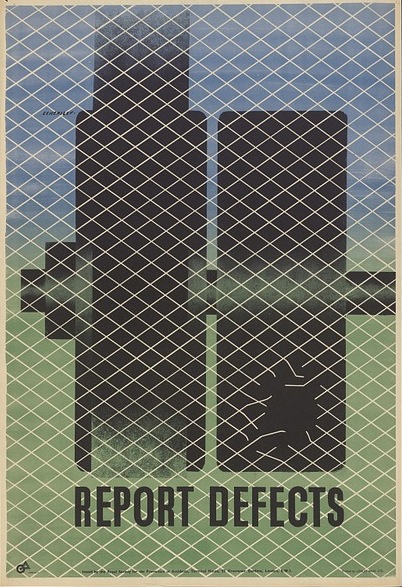

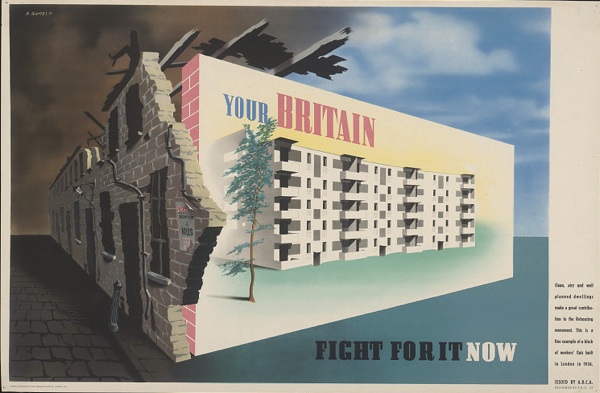

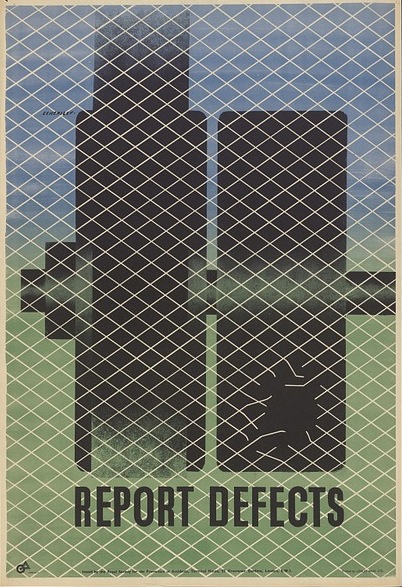

The other problem, though, is that curse of academia generally, the use of a language so abstract that it ends up utterly disconnected from its subject and floating away into the ether. Here is one sentence, on my current favourite topic of World War Two posters, as an example.

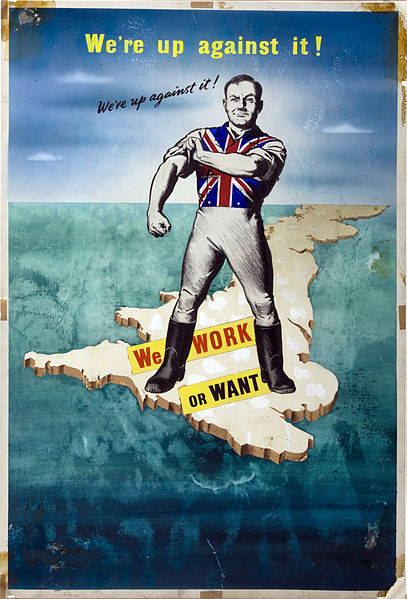

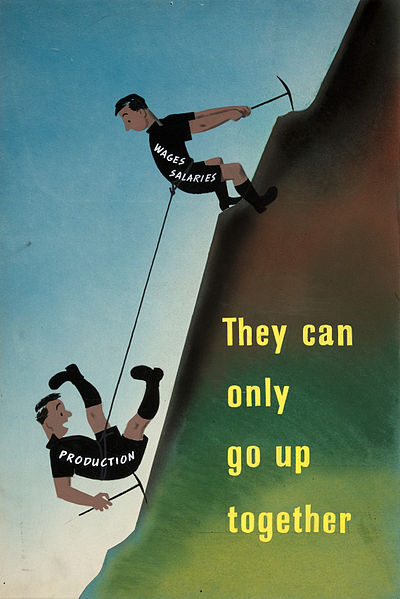

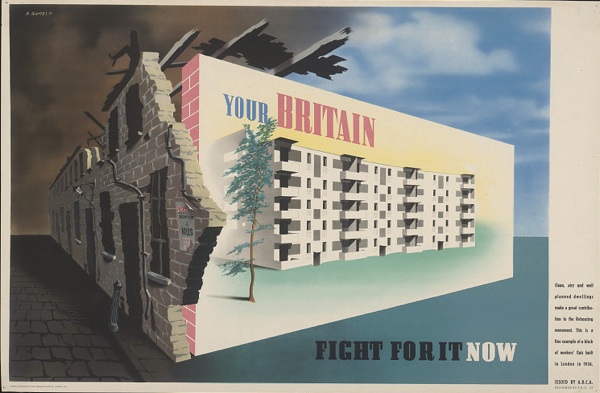

By balancing themes of collective sacrifice and citizenship with increased state responsibility for informing and protecting the people, war posters had set out a form of social contract between the government and the British people.

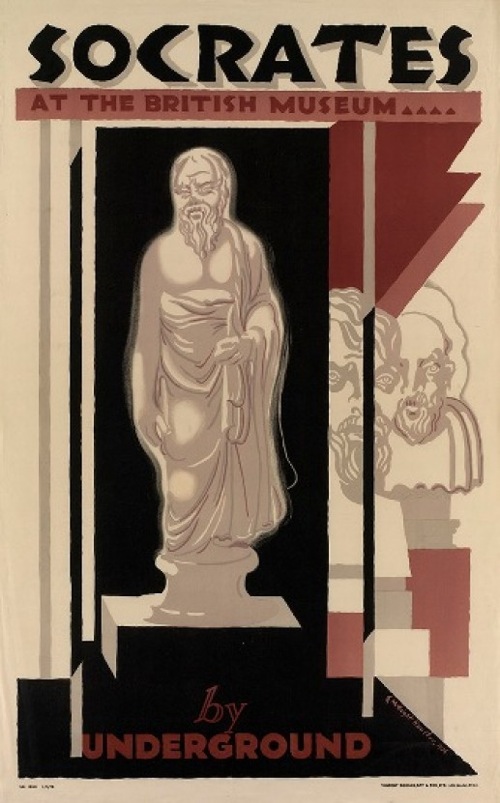

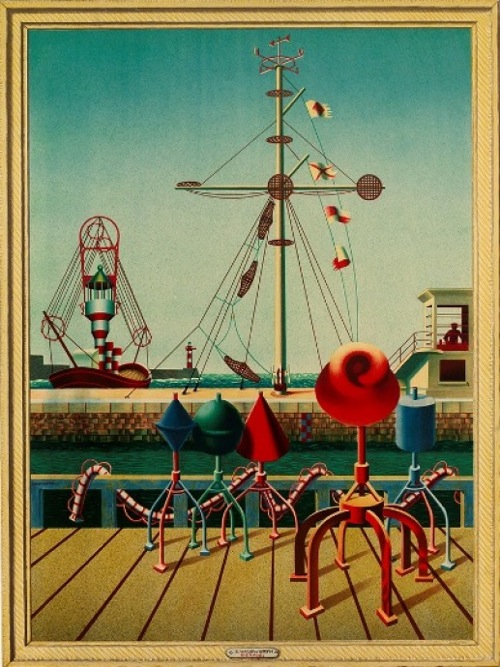

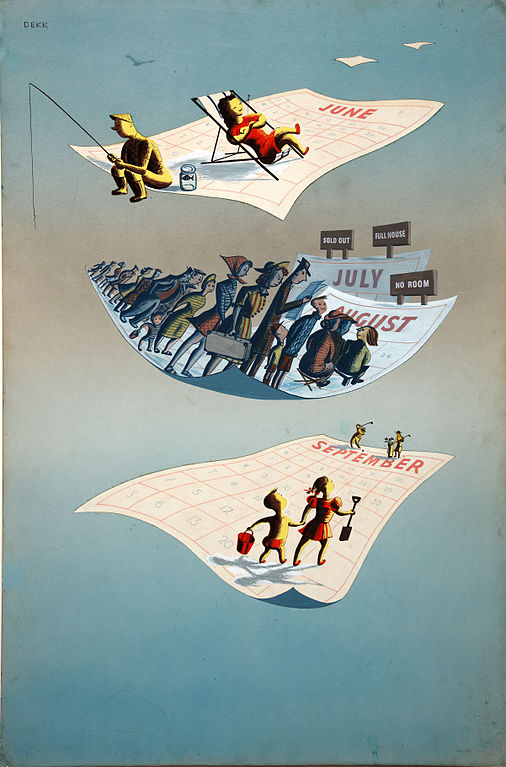

The only concrete noun in all of that is the word poster, although I might also allow contract at a push. But this does at least tell us something. Where I find the abstraction particularly galling is when the abstraction is given precedence over the posters. Take this, a fine piece of London Transport pair poster from 1950.

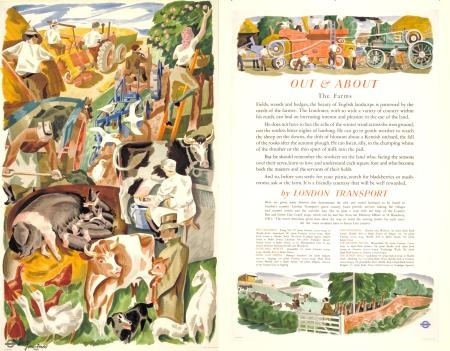

The poster is introduced by the idea that – oh it’s so abstract I can’t even paraphrase it – here you go in her own words.

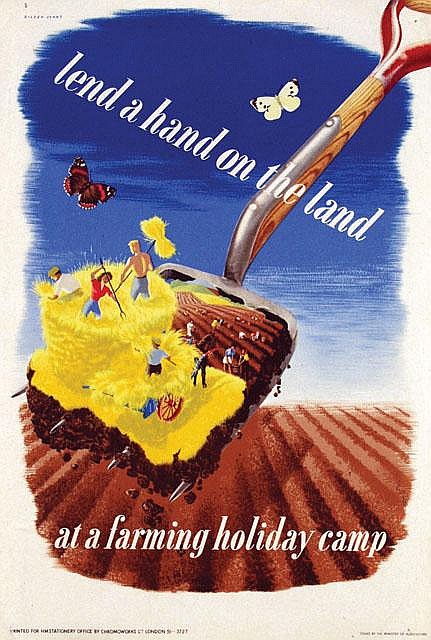

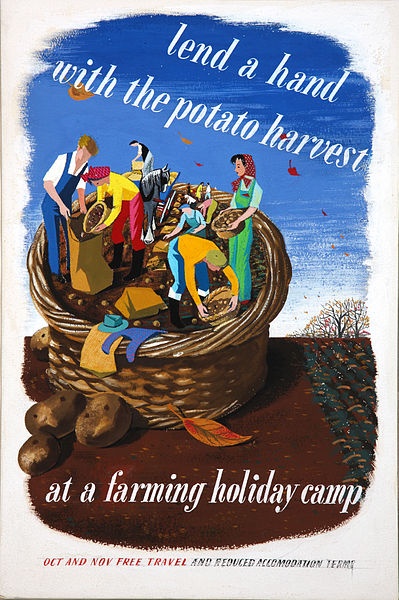

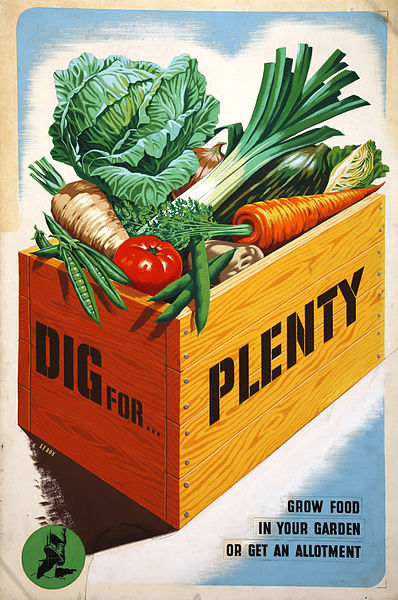

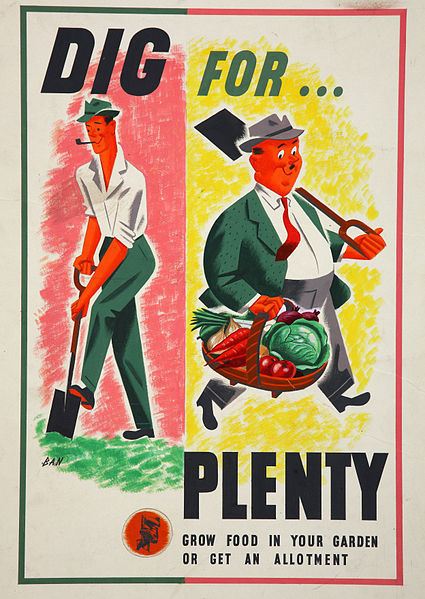

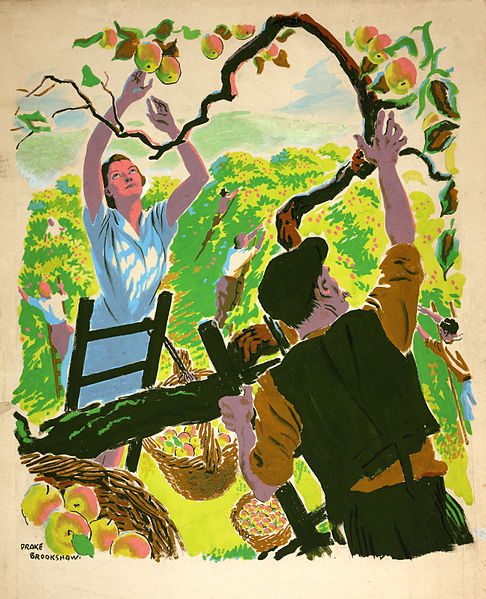

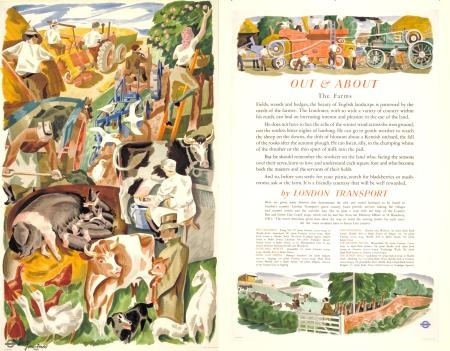

[posters] encouraging people to travel out of London had helped to foster an idea of the British countryside as a site of collective heritage and recreation. This romantic but democratic idea of the land gained institutional currency after the war with the creation of National Parks, Green Belt policy and the expansion of the National Trust, but was offset by the urgent need to increase agricultural production and drive forward the mechanisation of farming.

Land. I know what that looks like at least. But the language itself is not so much the problem – there is a point here and I can discern it floating high up there in the abstractosphere – as the conclusions it leads to.

Tractors and stockbreeding, two king-pins in the modernisation of farming, have a prominent place in the composition.

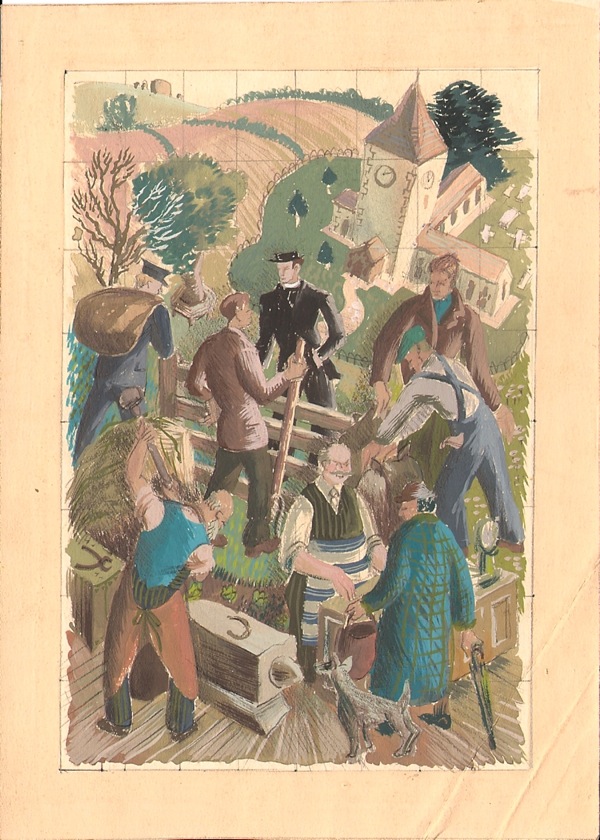

Now I could say a lot of things about this poster – probably starting with the implicit contrast of rural life when depicted in the very urban and mechanised environment of the underground, moving on to the neo-Romantic rather than modernist style, possibly influence of Stanley Spencer in the apple-picker and generally that it is rather good. If we were looking at the text too, perhaps it would also be worth noting that the poster feels the need to instruct the Londoner on why the countryside is good and how to behave in it, showing an estrangement between urban dwellers and the countryside. But the mechanisation of farming is hard to see in it, especially given that the steam powered thresher – given far greater prominence than the tractor – was even in 1950 a relic of the last century.

What’s happening here is one of my bugbears, an argument into which posters have been dragooned as supporting evidence. I’d far rather start with the poster and see what it might have to tell us.

So should you buy this book? I still don’t really know the answer to that question if I’m honest. If you’re more interested in art and protest posters than I am, then yes probably. If you’re me, or something akin to that? Well then yes, I do still think you should. Not only will you end up knowing more about the history of poster display, you may even end up having a creative argument with it to boot.

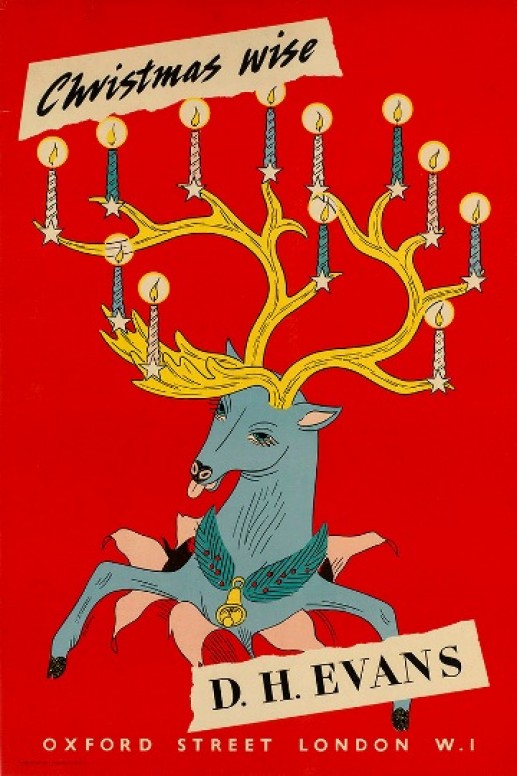

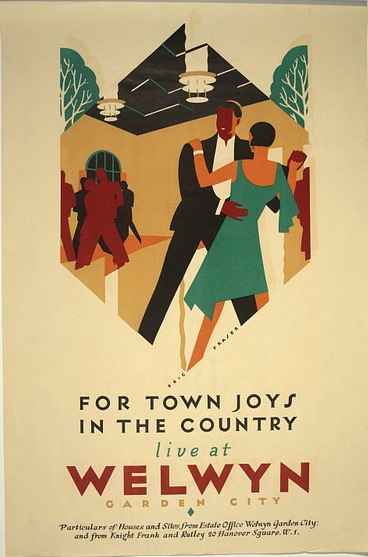

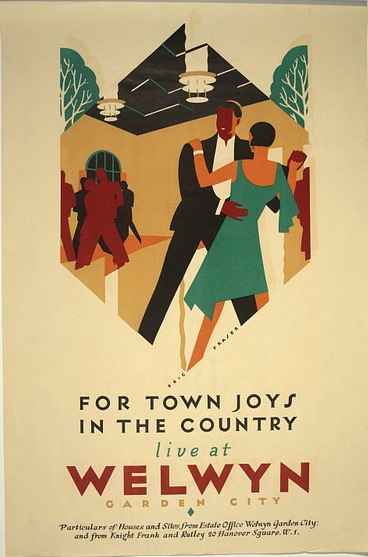

(Most of the images illustrating this post, incidentally, come from the V&A’s online archives. Now this is not only a selection by curatorial choice, but also further limited by the fact that only some of the entries have images with them. Even so, I find it strange that I couldn’t find a single English railway poster in there – the Welwyn one above was as close as I could get. It’s a very partial story indeed.)