I’ve just got round to watching Saturday night’s Festival of Britain programme, and wanted to draw your attention to it as it’s only on iPlayer until this coming Saturday. (Apologies, as ever, to those of you who are outside the UK and so can’t get hold of it.)

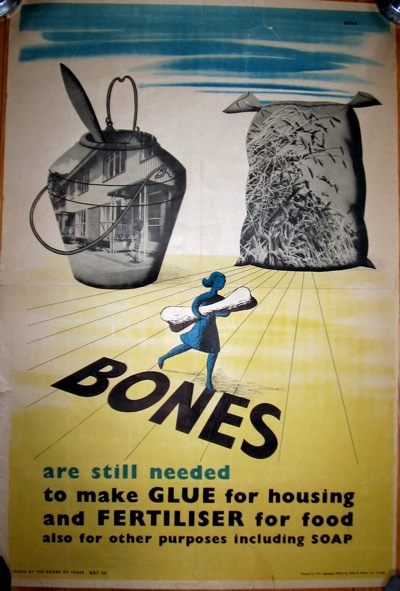

There are quite a few things to enjoy about the programme, not least seeing Dorrit Dekk interviewed on the television, and what’s more also spotting an archive picture of her with this poster in the background.

She wasn’t alone either, as they’d interviewed a whole host of original designers and visitors. Even better than that though, the programme is stuffed full of tons of contemporary colour footage of the festival, set to some great music. Whichever researcher found the calypso Festival of Britain song, which included amongst many memorable lines a paen to the Charing Cross pedestrian bridge, deserves a medal. And the editor too, for letting the whole thing run without interruption, so just sit back, put your feet up and let the festival spool past. (If you can’t be bothered to watch the programme, shame on you, but the song is by Lord Kitchener and you can find it here.)

There were, of course, irritations too. The same care in casting had not been applied to the modern day pundits, so representing the historians we had Dominic Sandbrook, who is it seems a compulsory part of any programme about this era, and Jonathan Glancey (ditto, any programme about the history of design and much else besides). Which meant, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the conclusions were no great shakes either. The Festival was very happy (this is probably true, but I’d still like another point of view one of these days). The Festival was Very Influential on architecture and design (stated, but never proven, and almost impossible to deal with given the programme’s almost infinitely all-encompassing definition of modernism). Council flats made people very happy in the 1950s (yes, but can we not try a little bit harder).

From all of this waffly unthinking, though, a couple of nuggets did manage to emerge. Despite Dominic Sandbrook’s ubiquity, he may yet have a purpose. He pointed out, and it’s true, that the Festival was a version of the future, not necessarily in the way it looked, but in its emphasis on technology and science, which prefigured the white heat of the 1960s. Interesting idea, give that man a television programme. Oh, hang on a minute, perhaps not.

The other thought came from one of the architects. Talking about how grey and depressing Britain was in the run up to the Festival, he said that no wonder the the whole country looked run down, because almost every house hadn’t had a coat of paint outside for the last ten years. It’s a small point, but one which makes that shabbiness as imaginable as can be. No wonder the Festival’s bright colours were so different, so appealing.

I really enjoyed watching this, especially seeing the Emett Festival Railway

The Hungerford bridge walkway was an army bailey bridge. These kinds of bridge are made up of standard parts and assembled on site.

The bridge was put up by Royal Engineers. My father, a national service officer at the time, helped with this job.

Putting up a bridge like that was an amazing achievement, especially when you consider the speed and volume of water in the Thames at that point.

The South Bank was designed to be approached from this river crossing and illuminated accordingly.

Best to you all

P