I have three ideas bobbing around in my head today, along with a suspicion that they are in some way connected, even if I can’t quite identify how yet. The only way to find out is to write them down, so apologies in advance if it turns out that they aren’t.

Let’s start with the most tangential, the North Sea Radio Orchestra. Who are brilliant, but so far off the topic of this blog that I won’t say much more than that, except that they are very English, historically rooted and pastoral (and thus also connected to yesterday’s post) but also modern. Trying to find out a bit more about them, thougb, I was struck by – that’s struck in the sense of really quite irritated by – a review of one of their concerts.

“it’s frequently a fine and lovely thing. But in some ways it can’t help feeling like a retreat… Certainly there are moments of beauty, but ultimately it’s like stepping back into an alternate, pre-war England where rock’n’roll – not to mention mass industrialisation and immigration – never happened. Which is fine for a night, but I wouldn’t want to stay.

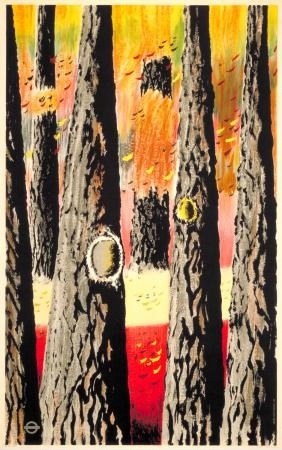

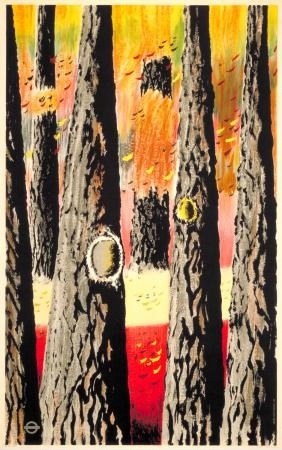

Out and About: Autumn Woods, Keith Cunningham, 1950

The implication here is that the modern world of cities and tarmac has wiped out the rural and romantic aspects of Englishness for good. Even at face value this is a fairly contentious statement: I live in a small town, the countryside is not very far from my front door and I can say with some certainty that, despite the factories, Tesco and a global economy, the fields and hedges are still there. But more to the point – at least for this blog – this sets out very clearly one point of view in a problem that I keep coming back to on Quad Royal, that of Englishness and modernism.

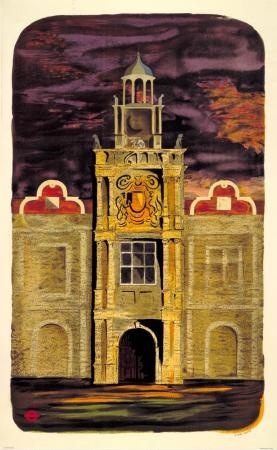

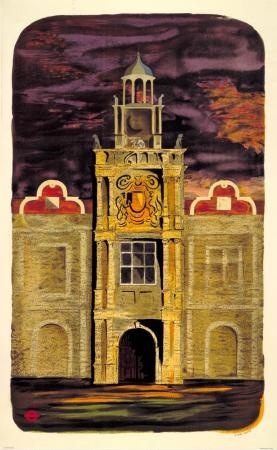

Out and About: Country Houses, S John Woods, 1950

For the reviewer (one Ben Graham, you can read his whole review here if you want), the modern tarmacadam world has made the ‘old’ version of Englishness, rooted in the pastoral and the historic, in the tracks over the fold of the hills, irrelevant. The real world is only now contained in the fluid city, in machines and cars and – for him at least – loud electric guitars. And while I’ve made the argument sound a bit daft here, this is in the end the central narrative of modernism. Only things which represent the streamlined bustling city can be modern, the rest is pointless, even reactionary. By which standards the English regularly and repeatedly fail at being modern in any way.

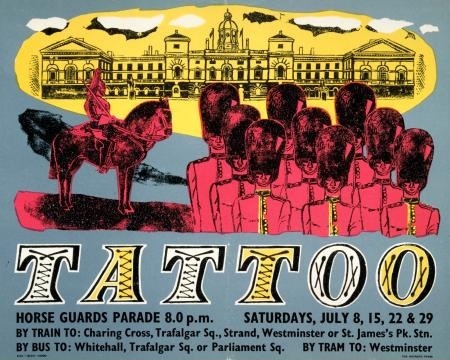

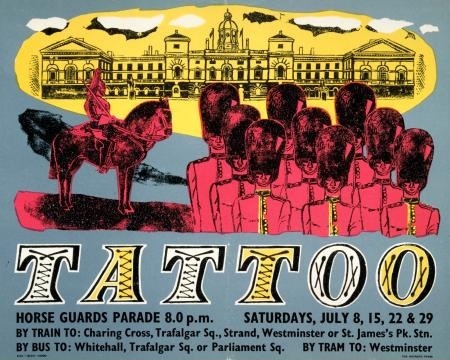

Tattoo, Anonymous, 1950

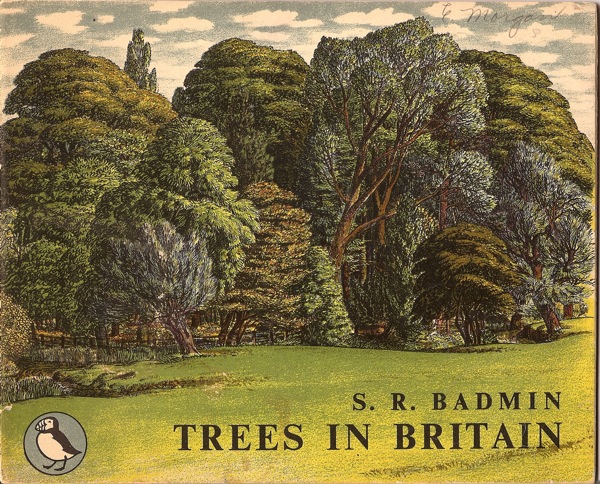

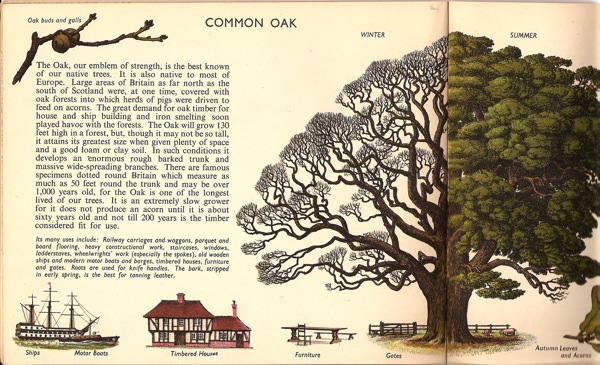

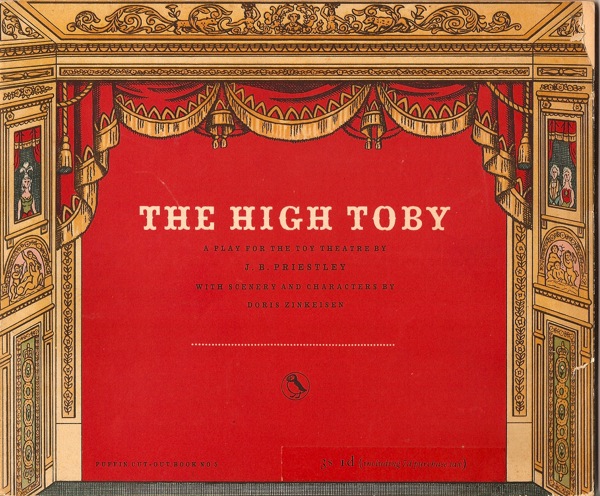

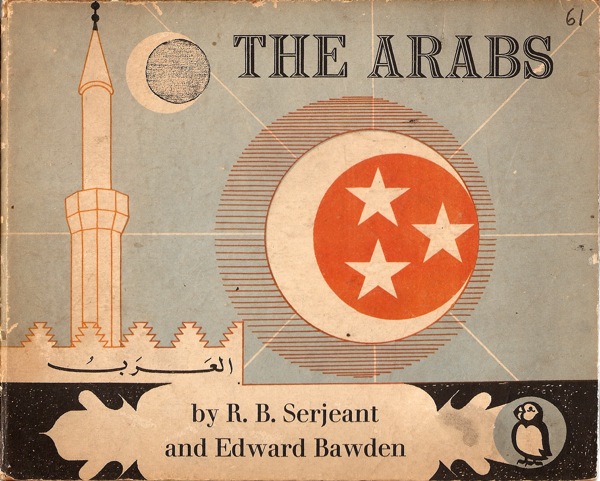

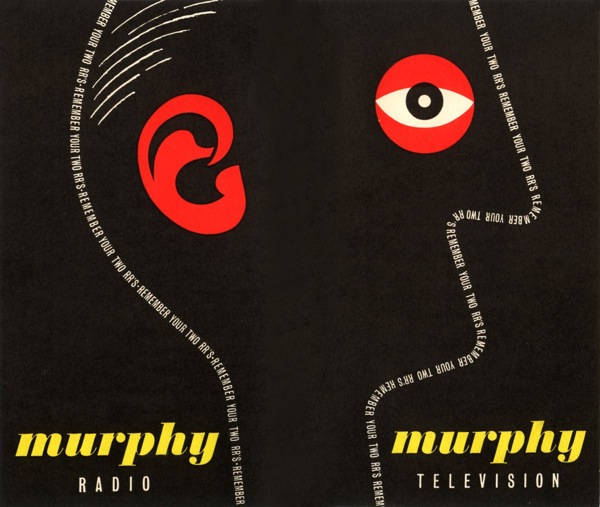

Another story is, though, starting to gain some currency (in this book this book for starters), which is that the British/English were producing modern design, and thinking about it very hard; it’s just that what they produced was a different modern which maintained a connection to older traditions as well. We live in a country which has both landscape and cities; modernism’s inability to reflect this was the failure, not us. So modern British design doesn’t always look like you expect. (And modern British music might not always have an electric guitar in it either).

for starters), which is that the British/English were producing modern design, and thinking about it very hard; it’s just that what they produced was a different modern which maintained a connection to older traditions as well. We live in a country which has both landscape and cities; modernism’s inability to reflect this was the failure, not us. So modern British design doesn’t always look like you expect. (And modern British music might not always have an electric guitar in it either).

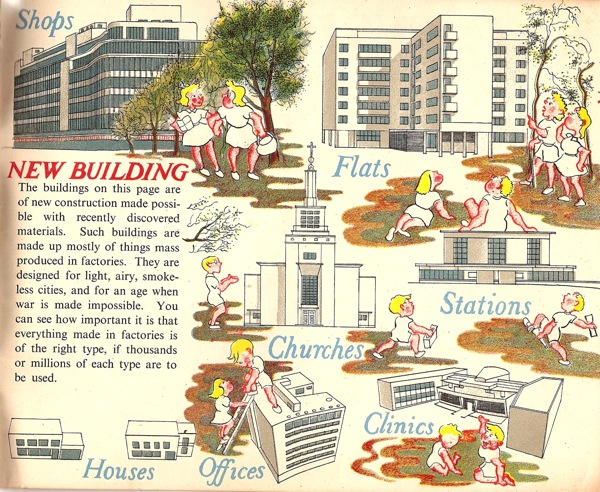

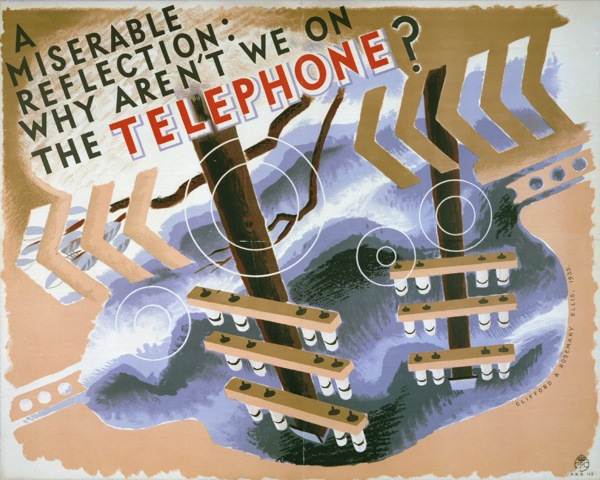

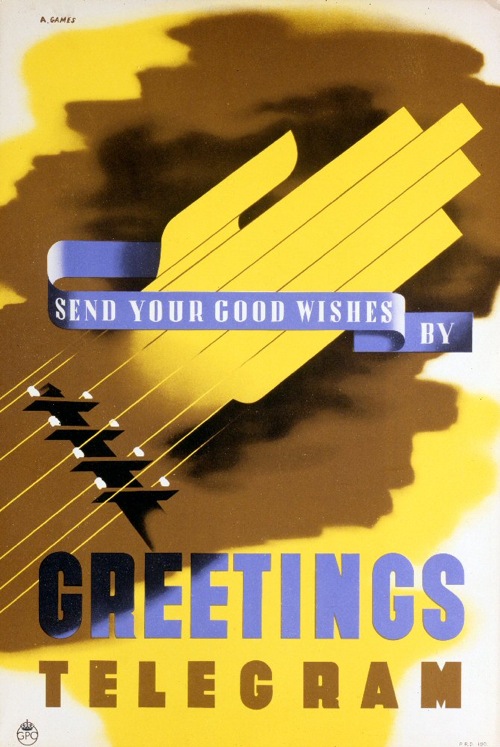

All of which brings me back to Graphis 31, the survey of British Graphic design in 1950. Now, if ever there was a moment in which Britain wanted to be modern, this has to have been it. A whole new post-war world was being built in which everything was going to be different, preferably with bright colours and all mod cons (this is, I know an over-simplification and I’ve put the opposite point of view on here before now, but I think it’s nonetheless true that if ever there was an urge for total modernity in this country, the early 1950s was that time).

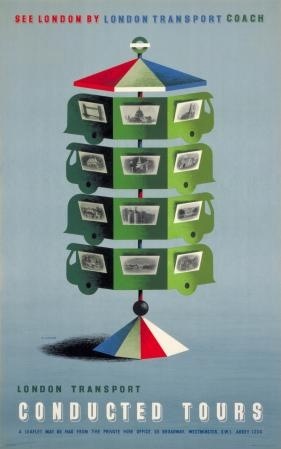

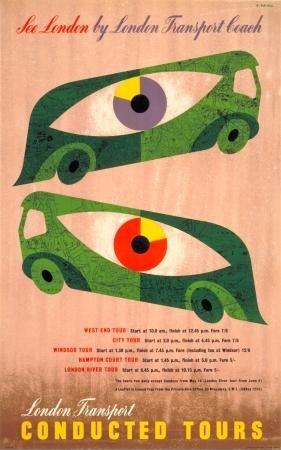

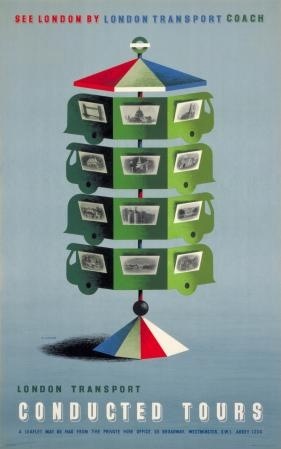

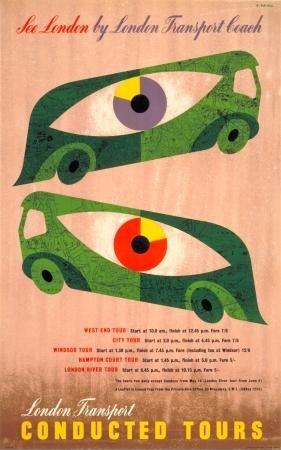

See London, Abram Games, 1950

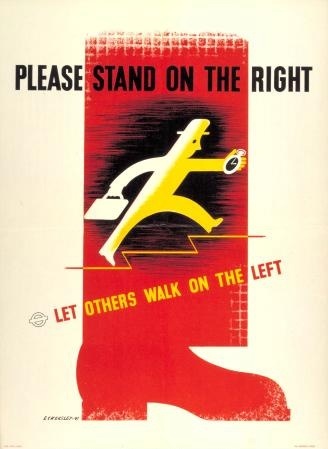

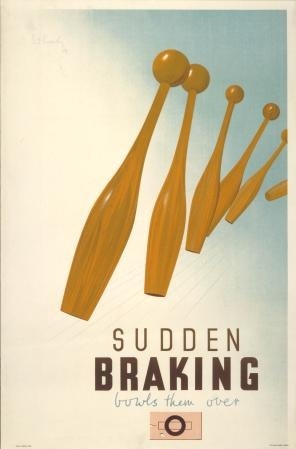

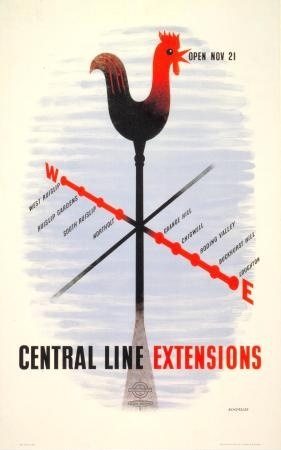

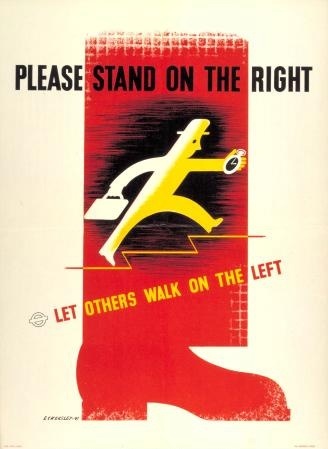

But when you look at the Graphis, the work just isn’t as ‘modern’ as you’d expect. Where I was struck by this most was in the case of the London Transport posters. Six are illustrated, and yes, some of them have the clean lines and modern styling that might be thought to signify this new world.

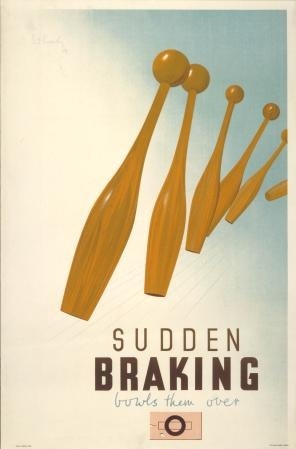

Sudden Braking, Pat Keely, 1945

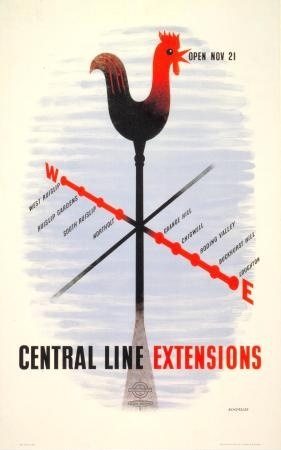

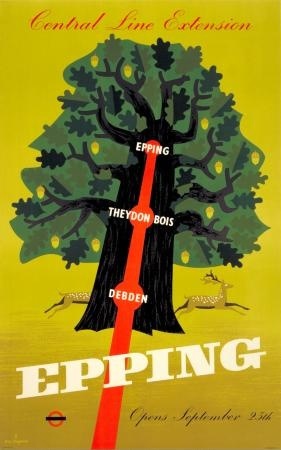

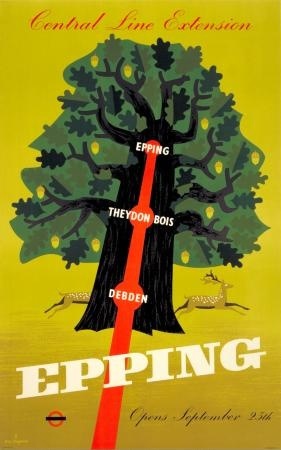

Central Line Extensions, Tom Eckersley, 1948.

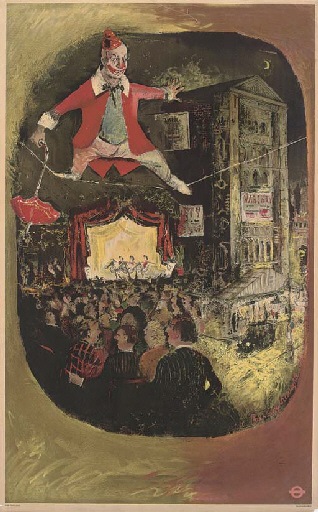

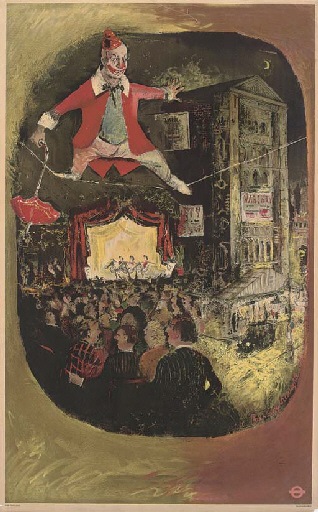

But quite a few of them don’t.

Lewin Bassingthwaighte, The Circus, 1949

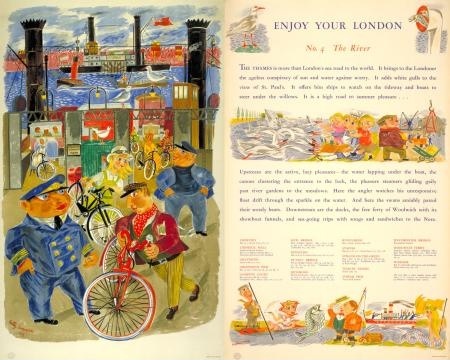

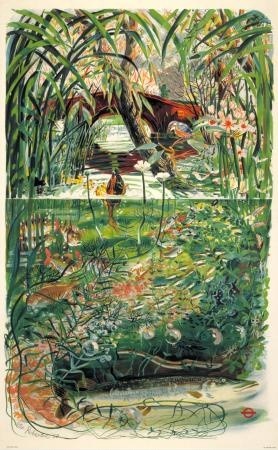

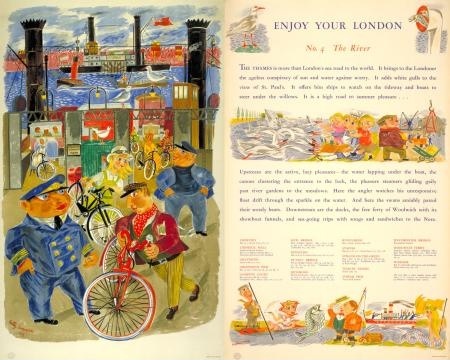

Betty Swanwick, The River, 1949

While this one just hovers somewhere in between the two.

Epping, C K Chapman, 1949

All of which brings me, by accident, to an idea that I’ve mentioned before, which is to take a slice through 1949 or 1950 and see just what the design really did look like then. I’ve always had London Transport posters in mind for this project, because it’s quite a comprehensive archive and one with, if anything, a bias away from conservatism (compared, say to product advertising), so it would be a tough proving of the theory.

Graphis has in some ways already run that test for me. The majority of the posters they reproduce are from 1949 (a year when, at least judging by the LT Museum archives, not that many posters were printed in that year anyway). I’ve supplemented this throughout the post with posters from 1950. And in terms of numbers at least, the victory is on the side of what we might as well call romanticism (i.e. the style of Graham Sutherland or John Piper) rather than the clean lines of International Modernism. What’s more, much of the modern design comes from the pen of just two designers, Tom Eckersley and Abram Games.

Please Stand On the Right, Tom Eckersley, 1949

See London by London Transport Coach, Abram Games, 1950

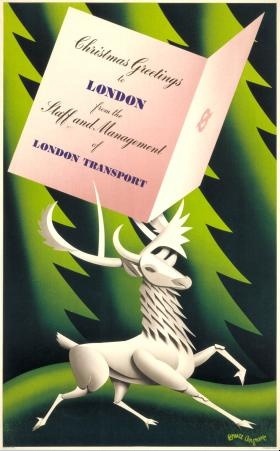

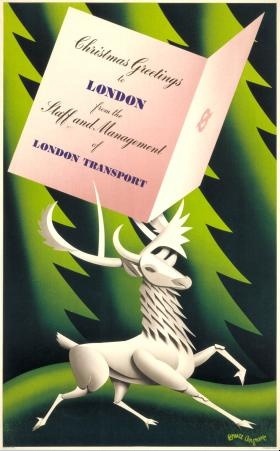

Although an honourable mention must also be made for this Bruce Angrave, just because it is great.

Christmas Greetings to London, Bruce Angrave, 1949

It’s also notable just how many designs use rural imagery too. Now this may be a function more of London Transport than the mood of designers at the time; after all, one of the purposes of the posters was to get people to use the Underground more, taking leisure trips out to the far flung – and still unspoilt – fringes of the network.

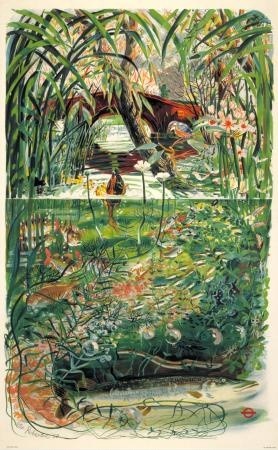

Out and About: the streams, Peter Roberson, 1950

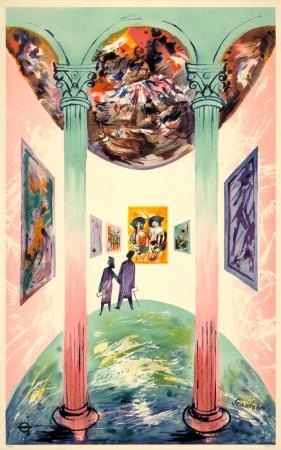

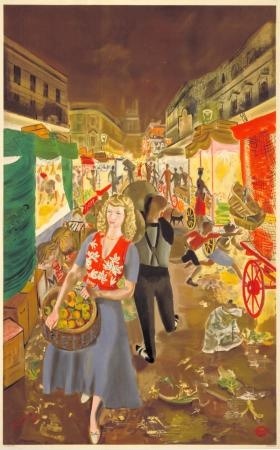

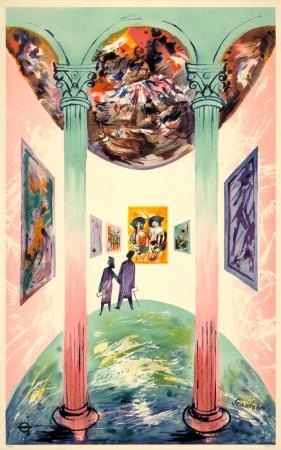

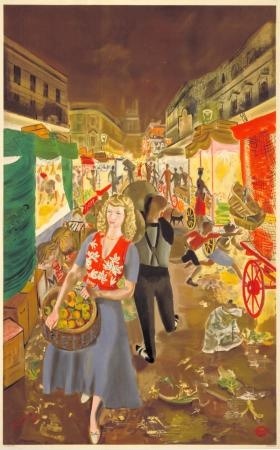

But even the images of urban life, of art galleries and street markets, are done in a similar style.

Enjoy your London: Art Galleries, R Scanlon, 1949

Enjoy Your London: Street Markets, A R Thomson, 1949

So does this mean that all those designs weren’t modern? Far from it. Because remember what I said up there about Sutherland and Piper? These were modern artists in the Britain of the 1950s, working in a new style. I’d be quite happy to bet that if you were a commuter standing on a Tube platform in 1949 or 1950, these posters would have seemed fresh and exciting, as modern as can be. Even though they don’t always represent the mechanised city in action, in the appropriate style.

Which leads me to two thoughts. One is that modern can perhaps only be judged at the time – if it seemed new, different, exciting to the eye of a bystander when it was produced (worthy of inclusion in Graphis, say) then it was modern. From a distance it’s all to easy to exclude things that don’t fit our historical preconceptions of a time, so perhaps we’re not necessarily best placed to judge.

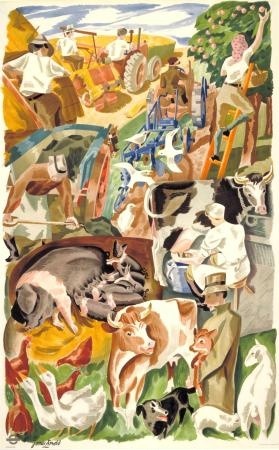

The other is that British or English modernism is perhaps more subtle and balanced than its European counterpart. To paraphrase Patrick Wright, we are always aware that we are living in an old country, and so we have to include this past into our depictions of the modern world, otherwise we are not telling the truth. The fields and their earthworks are always still there, however many industrial units we build.

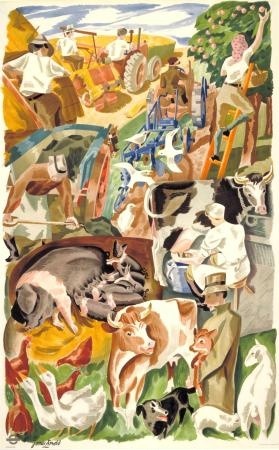

Out and About: the farms, James Arnold, 1950

Which means that modern design doesn’t have to have clean lines and sharp edges all the time. And our music doesn’t have to be rock and roll either. In which case I’d very much like to recommend I A Moon by the North Sea Radio Orchestra. It’s very modern, you see.

by the North Sea Radio Orchestra. It’s very modern, you see.