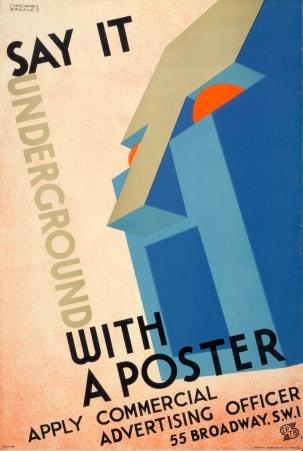

Say it with a poster

This week really isn’t going according to plan, and as a result I have not had much time to write. Apologies for this. I would like to say that the service will get better next week, but it’s the school holidays and I have a pub to rebuild. Hey ho.

Not all of this unexpectedness is bad, however. One good thing is that Quad Royal has been noticed. To be precise we’re one of the Top 50 Blogs of 2012 in BBC Homes and Antiques Magazine, sandwiched between All Things Considered and Spitalfields Life, which is illustrious company indeed, and I am very grateful.

Shall I tell you what they said too (just in case you can’t be bothered to click on the link)?

The authors of this informative, thought-provoking blog are two avid poster collectors, ‘Mr & Mrs Crownfolio’, with quite particular tastes – namely British posters and graphics from the Forties, Fifties and Sixties. Read it for the content (you’ll learn a lot), the images (fabulous) or the details of upcoming auctions.

You may consider me very chuffed indeed.

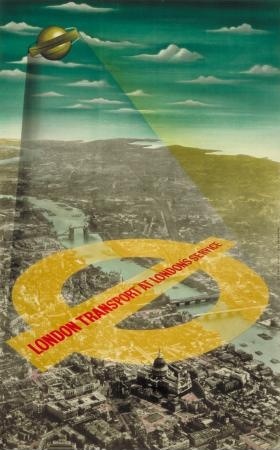

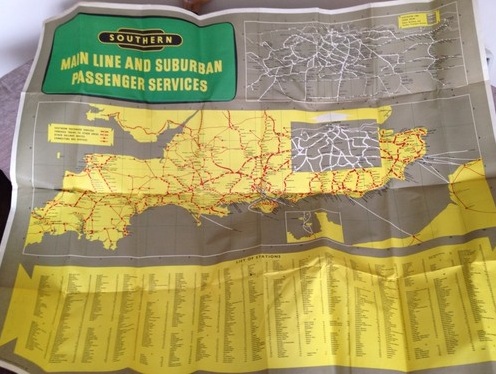

The other surprise was advance notice of the Christies October Poster sale. Yes, October, really; I was a bit hornswoggled too. But this is not your average Poster Auction, oh no, this is a London Transport Museum Poster Auction. Once again, I’ll let someone else do the talking.

The Museum manages one of the greatest poster collections in the world, thanks to the vision and legacy of one man: Frank Pick. When Pick became manager of the then failing Underground Electric Railway in the 1900s he initiated a modern, colourful, poster campaign which has been continued ever since. […] Fortunately, London Transport (as the Underground became known from 1933) kept duplicate copies of most of the posters it produced, and it is from this collection of spares that the selection offered for sale is drawn.

Although that doesn’t really give you a sense of the scale of the auction at all. You really need to imagine that they are selling all the London Transport posters you have ever seen, in museum condition, and then adding a few more on for good measure too. And then a couple more after that, just in case.

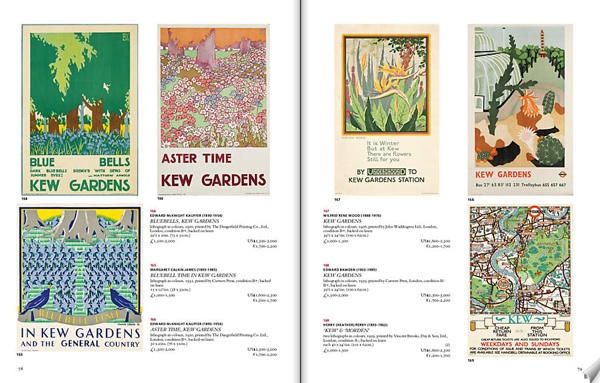

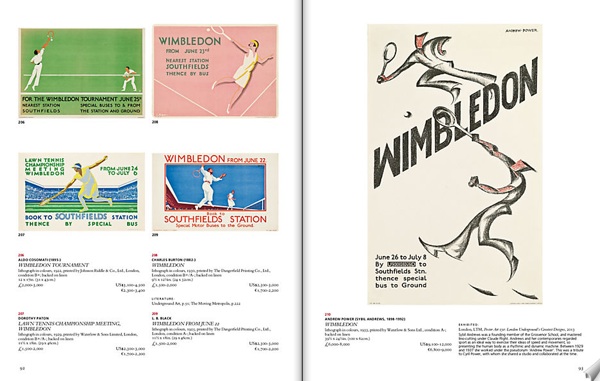

Taking individual posters out of context doesn’t really do the sale justice though, the e-catalogue, with its thematic arrangement, is much more impressive.

Normally I find these page-flicking simulacra rather annoying, but in this case it’s well worth the effort.

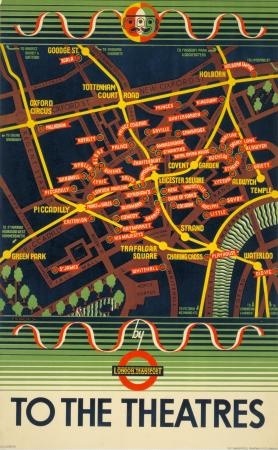

This is not only because of the scale of what is up for sale, although that is impressive enough. But they’ve also included pictures of the posters out in the wild, at Tube stations.

Like this poster.

Seen here at Osterley Station.

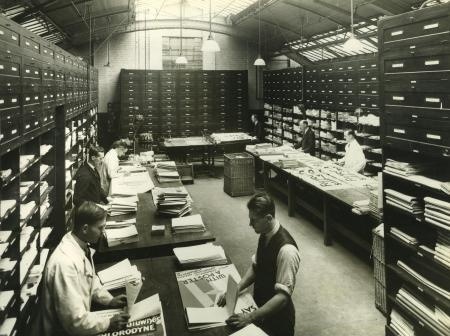

There is also a photograph of poster nirvana, the London Transport Advertising Store in 1933.

Another strong case for inventing time travel if you ask me.

There are 153 pages to go through, so all I am going to do in this post is scrape the surface of what is on offer. I’ll go back nearer the time and look more closely at prices and individual posters. I may even have to, heaven forfend, pay Christies for an actual copy of the catalogue just so that I can take it all in.

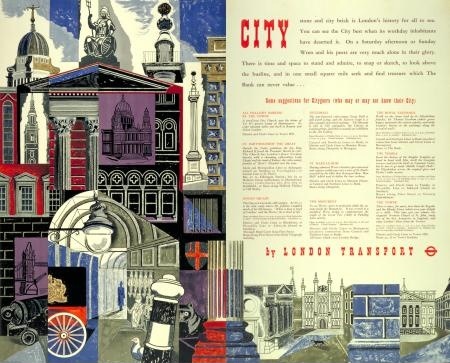

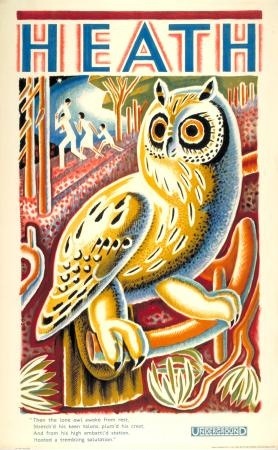

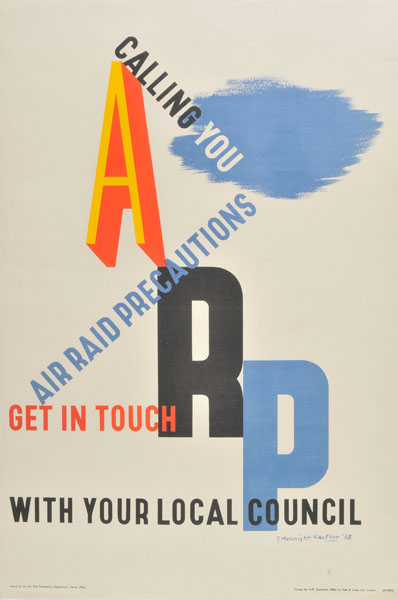

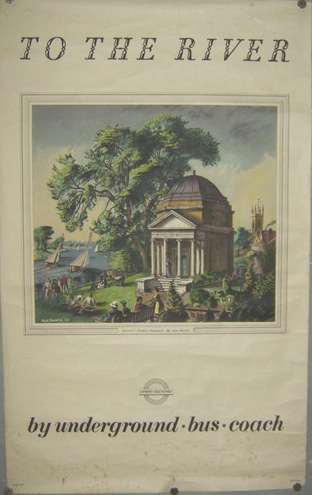

But one thing does strike me on a general level. In the nicest possible way, these are not my posters. There is the odd exception, like this Edward Bawden.

We sold a copy of the pictorial side of that pair poster a few years ago. And as is the case with almost every single half-decent poster that we have ever sold, I now wonder what on earth we were up to. But never mind.

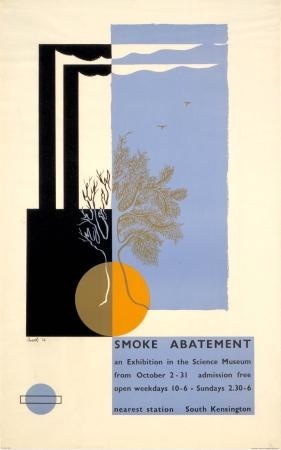

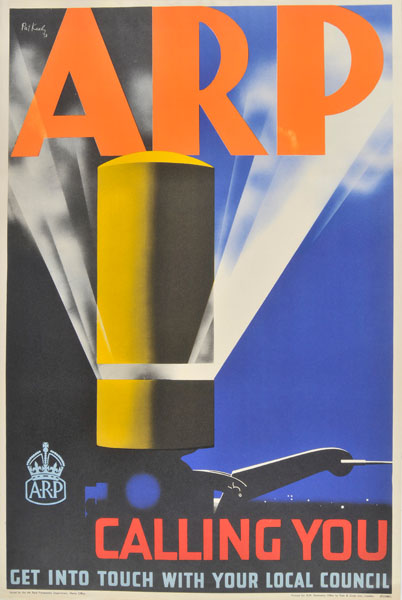

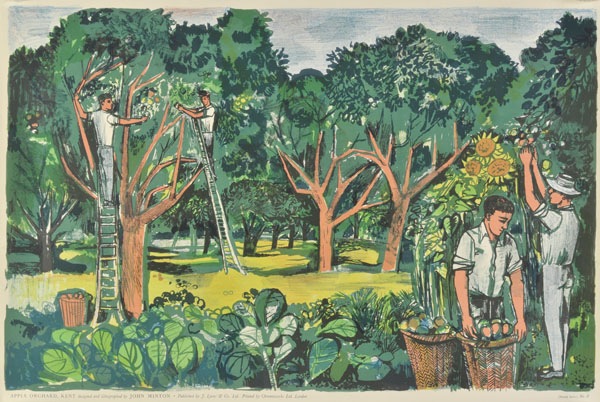

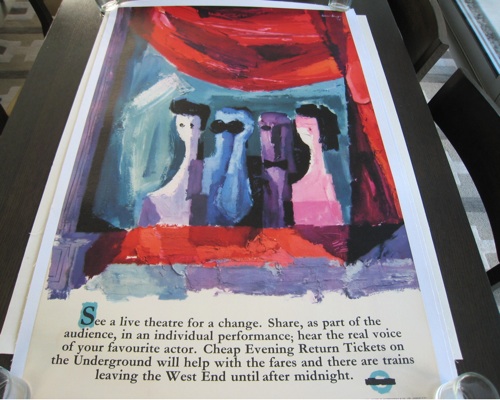

I also like this one too.

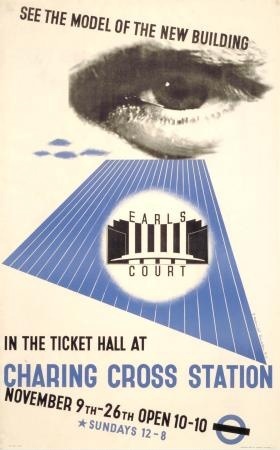

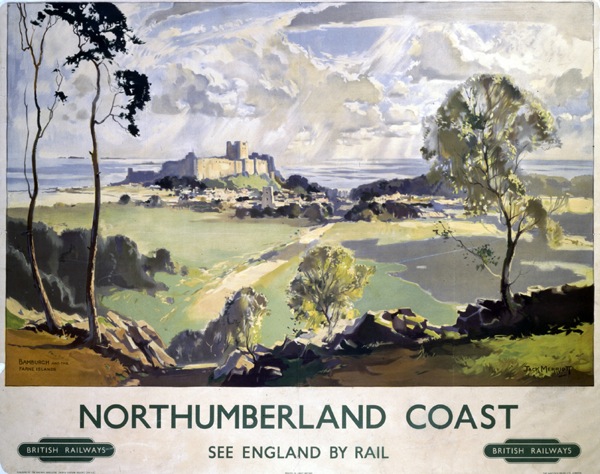

And this one.

Not that I can afford any one of them, but never mind.

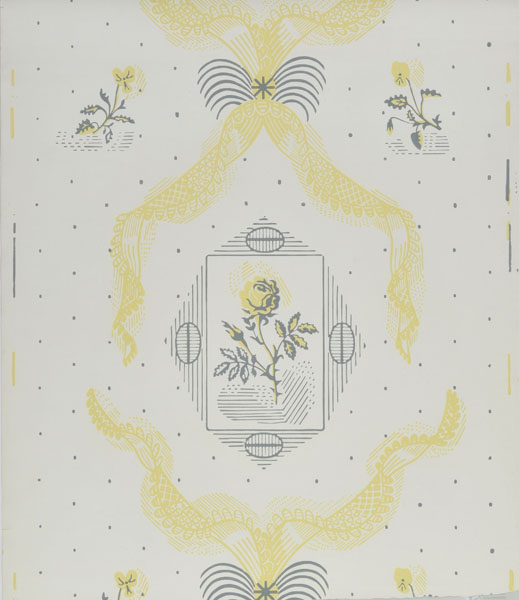

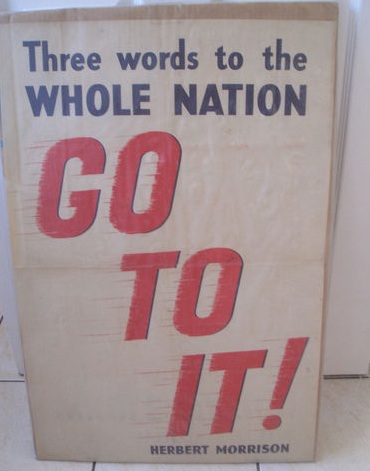

But these are almost entirely pre-1950s London Transport posters. I can pick out the modernist ones, but there is also acres and acres of Deco and decorative to wade through in the catalogue. But not a scent of very much at all post-war, bar the odd Bawden and this Abram Games.

Now this isn’t an accidental choice, I don’t think. The museum has made an interesting decision here, about what to sell and why – at least assuming that they have similar duplicates of the later posters too, which I am sure they do. The Transport Museum, along with Christies, may be guessing that the pre-war Deco-style posters have reached the top of their value. Whereas the later posters are worth hanging on to because their worth may yet go up further.

Now no one is ever going to admit this out loud, so it can only ever remain guesswork on my part. And of course all the Museum are doing are trying to be canny investors in their stock, which in this case is posters. They’re hoping that they are getting out at the peak of the market – but they might be wrong and the market might yet go up further. No one knows for sure, not even this owl.

But if they are right, then would you want to buy a poster from this sale? Well you would if it was one you’d been after for ages and wanted to hang on your wall, that would be very sensible. But if you are buying it as an investment? Particularly considering the, um, quite optimistic valuations on what’s on offer (or, if I am more cynical, the decision to put every poster at £1200+ apart from the really expensive ones).

Anyway, we’ve got plenty of time to consider this between now and October. But there is method in Christies’ madness; the announcement is now because 60 of the best posters are going to go on show at their King Street salerooms from now – I think – until 24 August. This might just be worth a visit. Because I don’t think I am going to be buying anything.

[And yes, the names of the poster artists aren’t on there yet because I have run out of time – this will be fixed at the weekend I promise!]