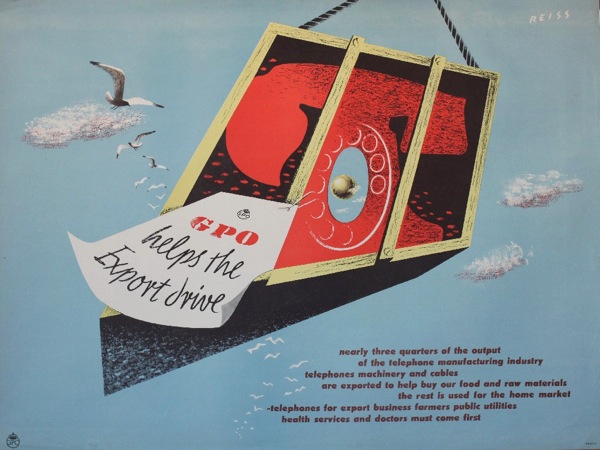

RIP COI

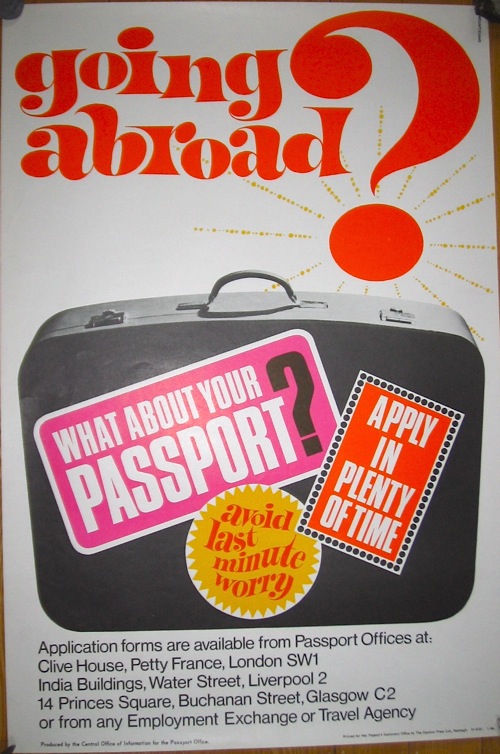

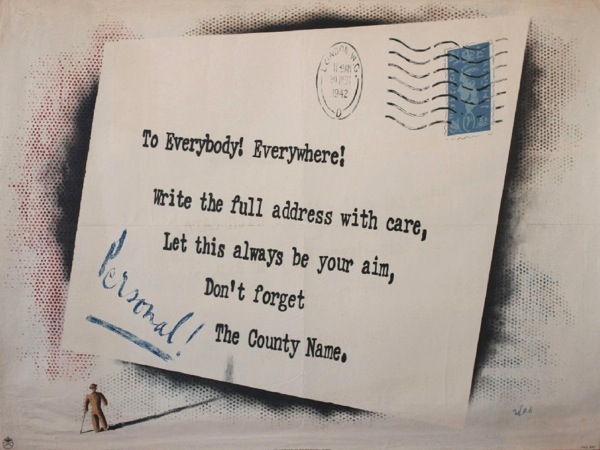

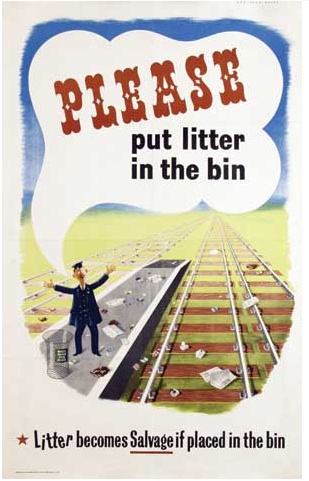

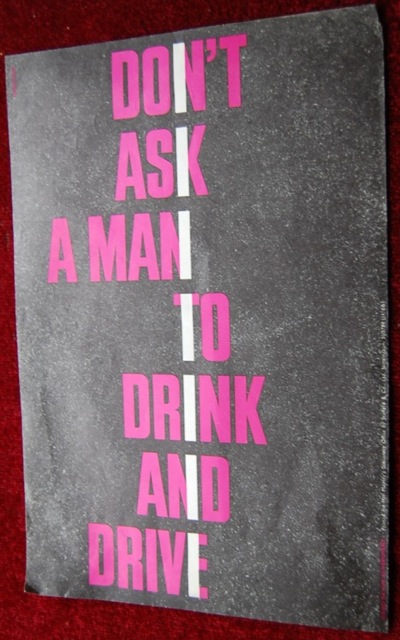

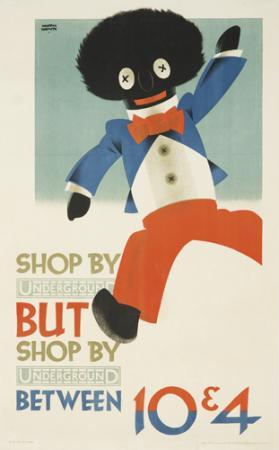

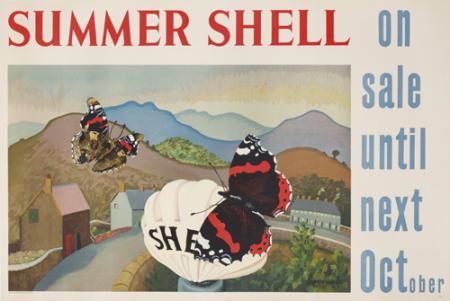

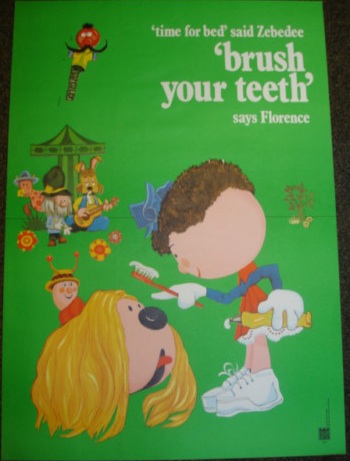

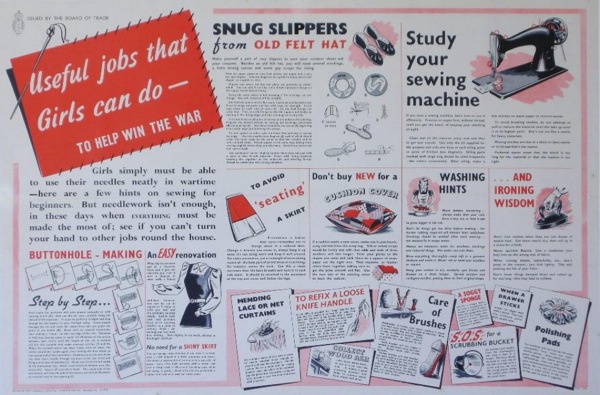

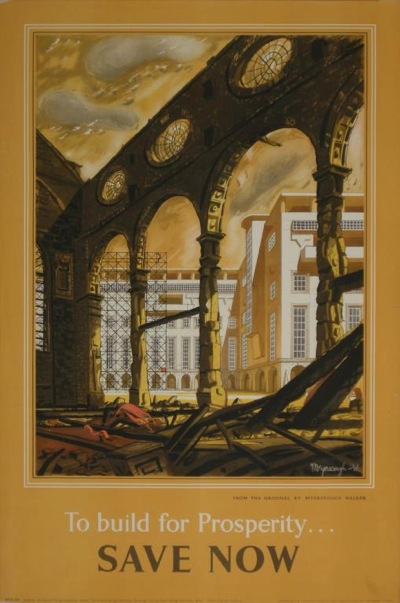

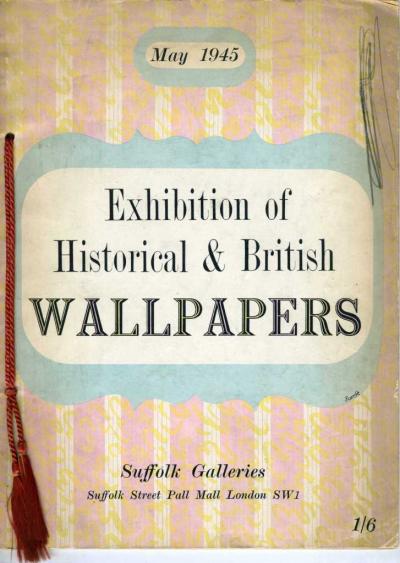

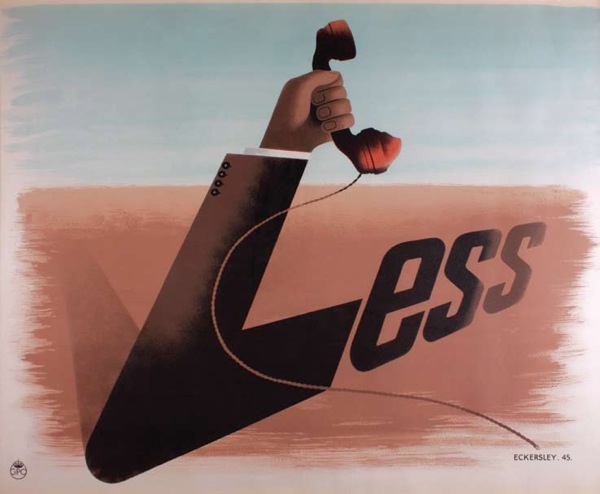

So the Central Office of Information is to be no more (news here in the Guardian). This is a sad end because once upon a time they produced some rather wonderful posters. Here’s a handy thought from them for this time of the year.

Coincidentally, I reccently bought a history of the COI from Abebooks. (I don’t suggest you do the same: this would be the driest book I have come across for some time, had it not been beaten by History of The Second Word War: Food Volume 2 – Studies in Administration and Control which currently sits on my desk, waiting to bore me out of my wits.) The real problem, at least as far as I am concerned, is that the book doesn’t mention posters much. Here’s pretty much the most interesting – or at least relevant – paragraph in the whole thing.

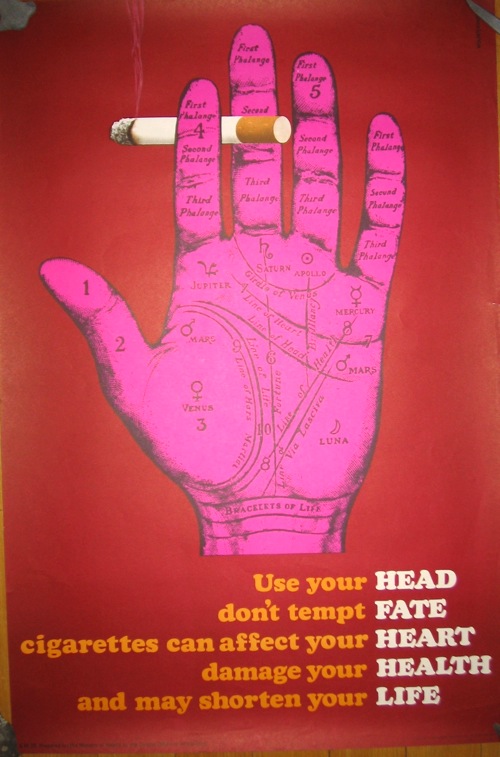

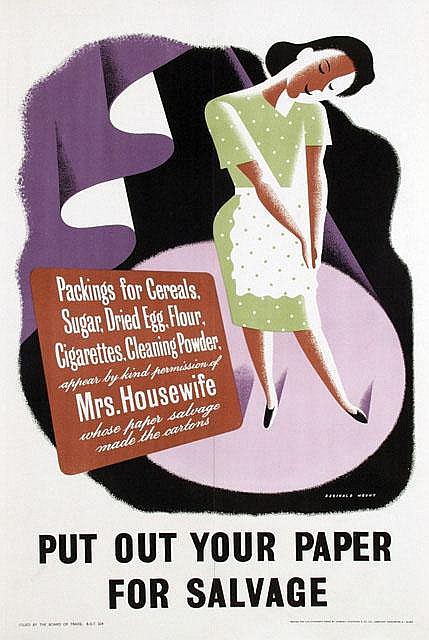

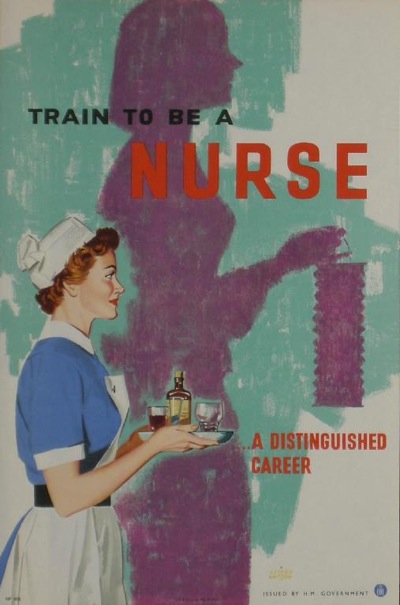

Over this entire period [i.e. since 1946] the COI has also had the part-time services of Reginald Mount and Eileen Evans as consultants and designers of a long succession of award winning posters, most notably for health education.

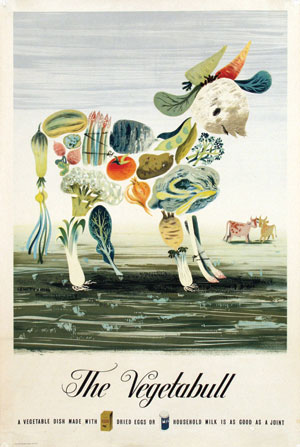

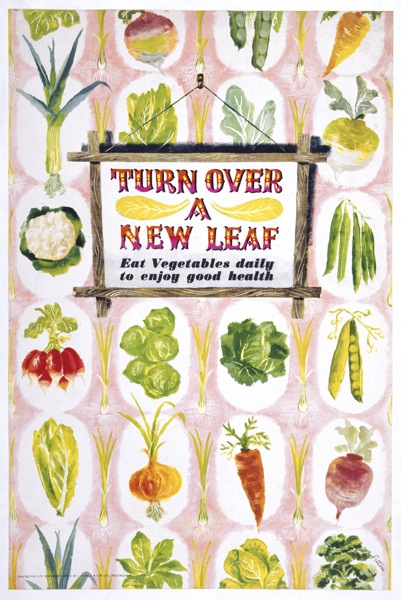

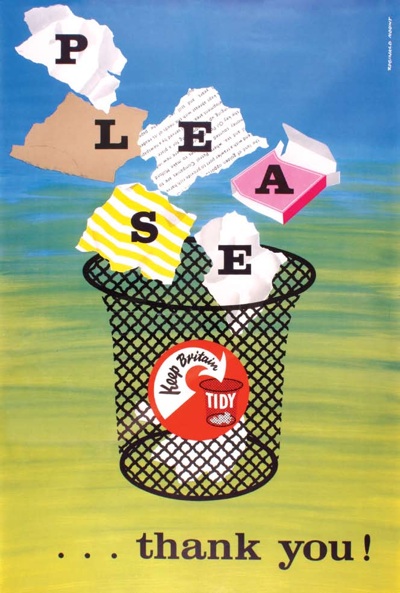

Posters like this.

Which does at least answer the question I raised a few weeks back, which was when did Mount/Evans leave the COI and set up on their own? Although the answer does seem to be a kind of Schroedinger-esque uncertainty principle in which they both left in 1946 when the COI was founded and at the same time never left. I suppose that as long as we never look in the Ministry box, it will be fine.

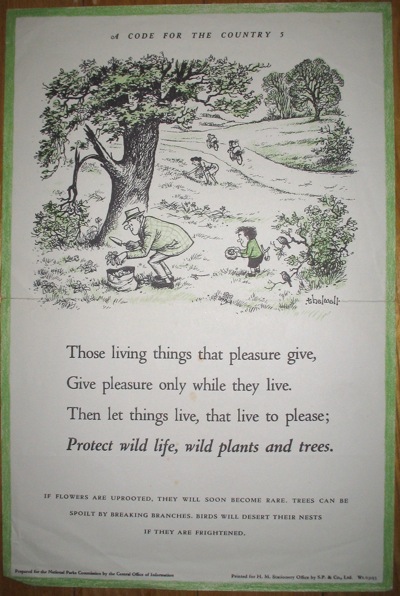

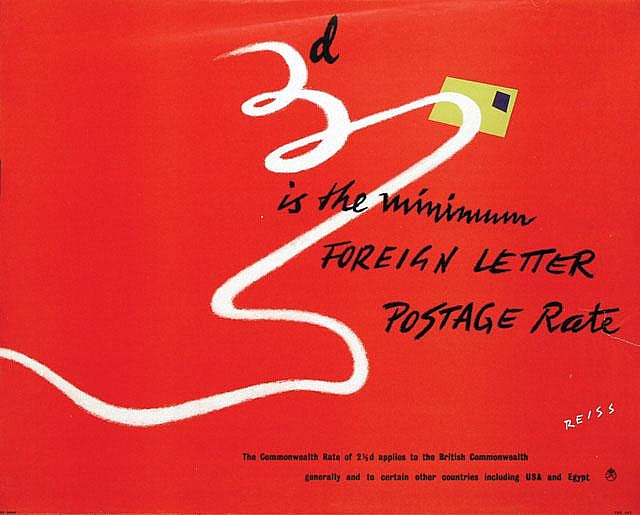

What does seem to be true is that the vast majority of the COI posters I have come across seem to be by either Mount/Evans or Reginald Mount on his own. My very slightly anal database tells me that we have had 28 COI posters at various times, but with very few other artists represented. One is Thelwell, who produced a whole series of Countryside Code cartoons.

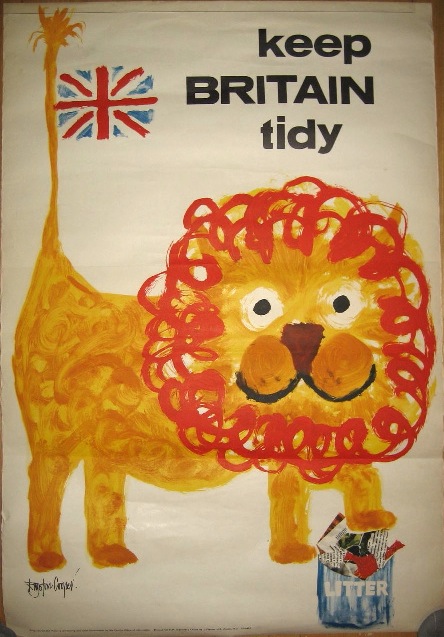

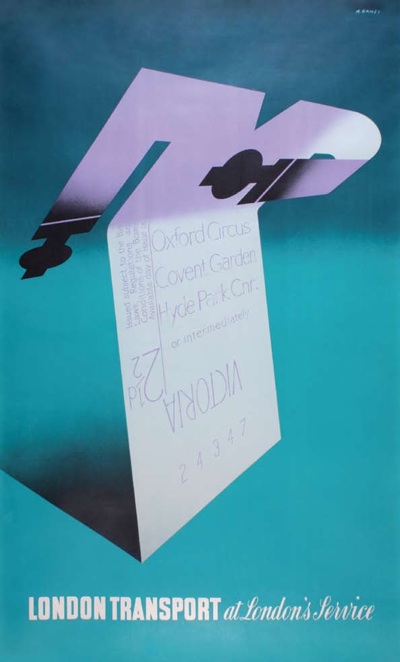

While the other is the magnificent Royston Cooper.

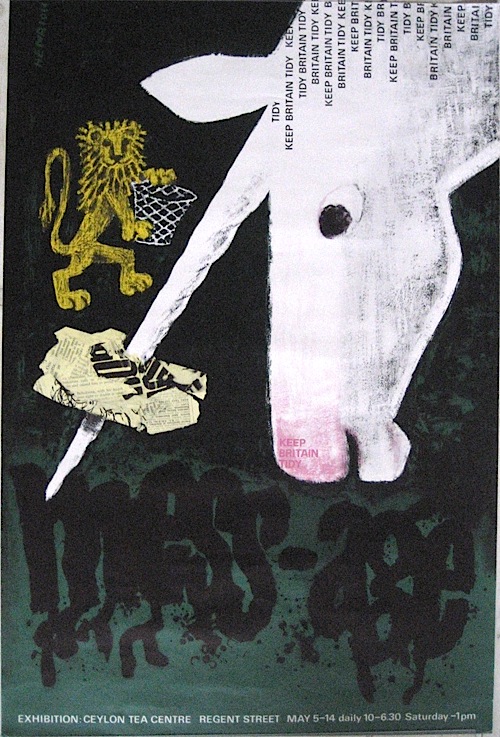

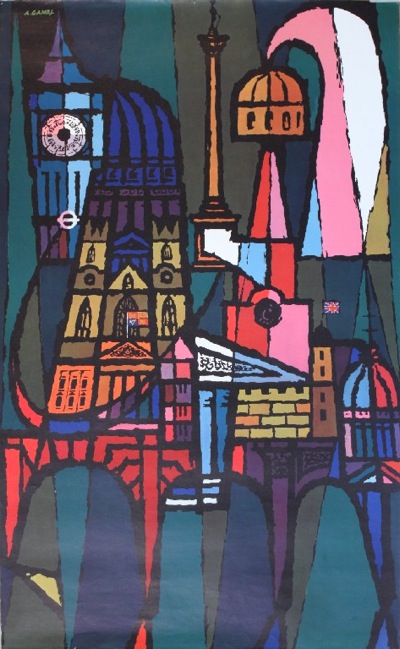

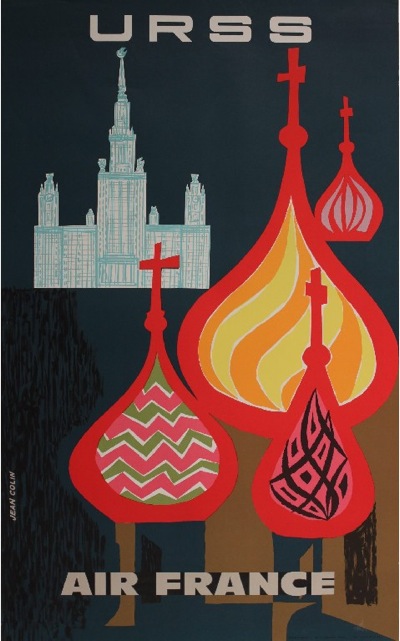

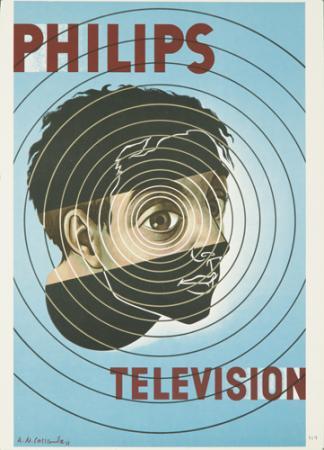

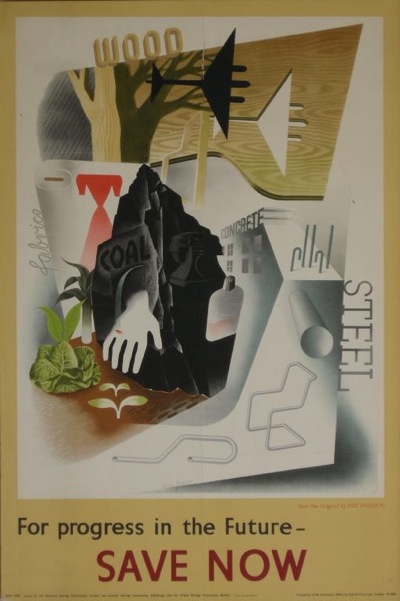

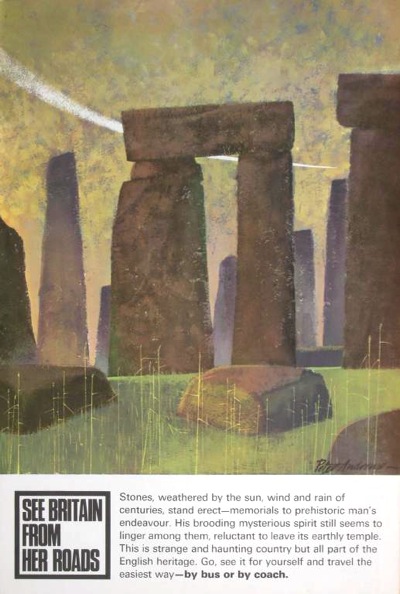

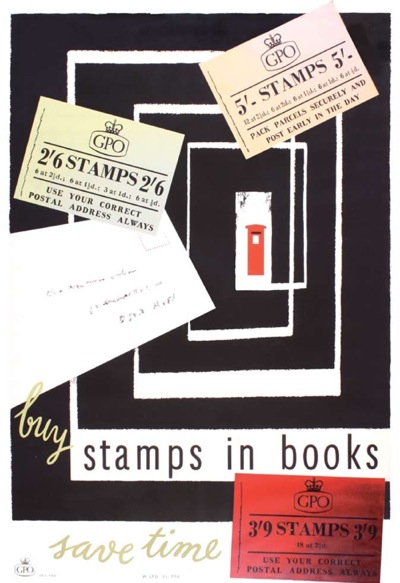

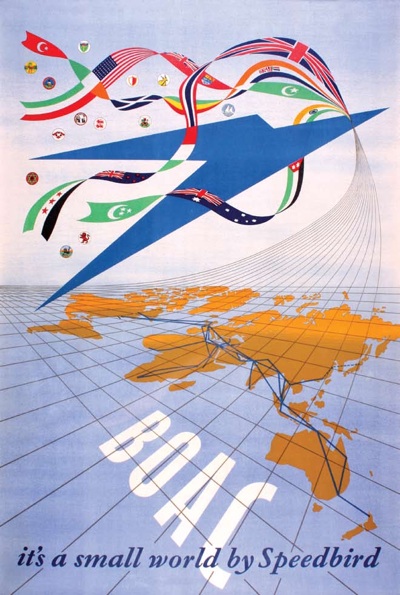

I also suspect that this Henrion may also be a COI production, but can’t prove it.

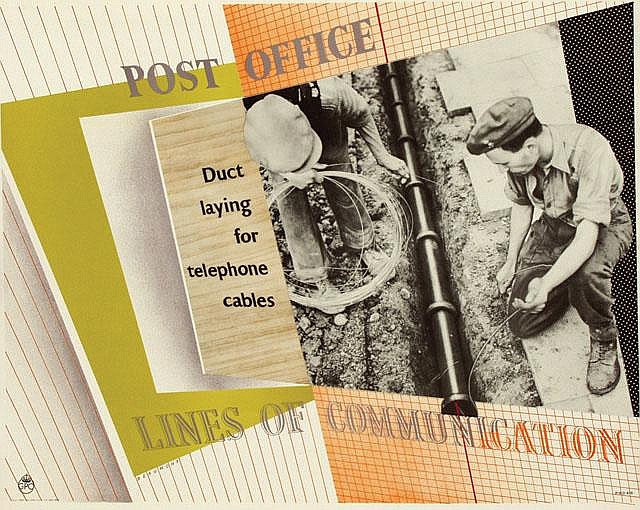

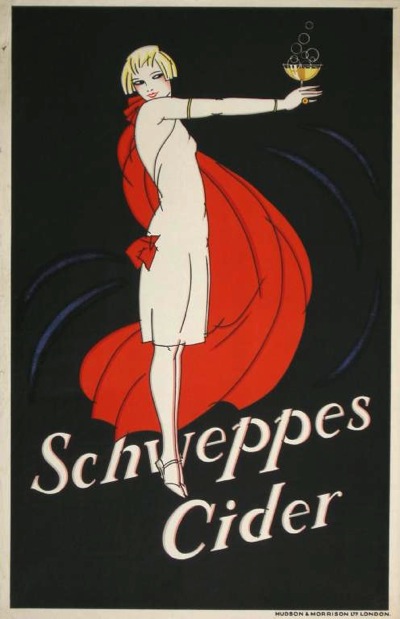

But that’s almost it. Which is surprising, because the COI book has a list of designers who worked for them, and it reads like a who’s who of graphic design in the 1950s and 60s.

For posters and book illustrations in the department’s lifetime these have included Rowland Hilder, Milner Grey, John Minton, Topolski, Ardizzone, Abram Games, Ashley Havinden, F H K Henrion, Hans Unger, Eckersley, Laurence Scarfe, James Fitton, Ronald Searle, Edward Bawden, Andre Amstutz, Tunnicliffe and the Crosby/Fletcher/Forbes group.

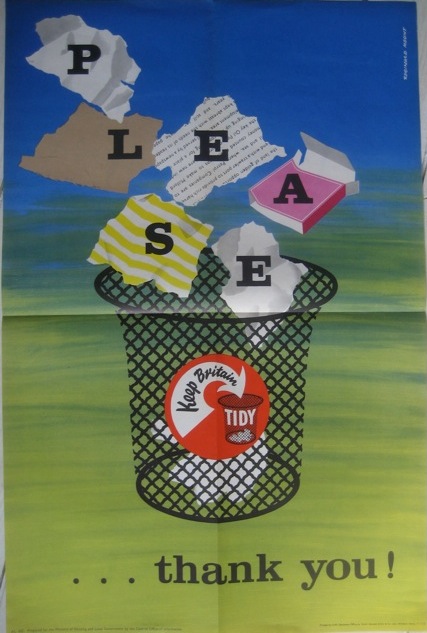

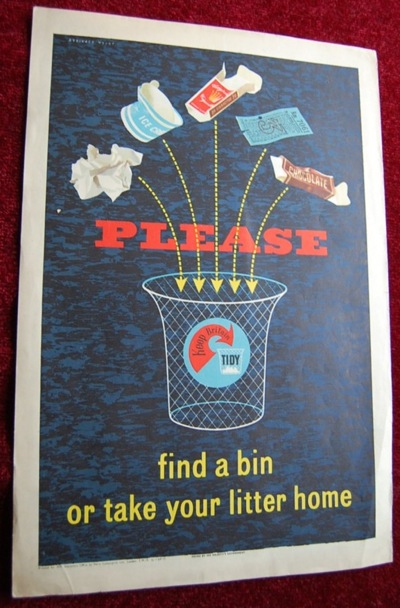

Now, I can see that our collection is a bit skewed, simply because we bought a lot of Mount/Evans posters at auction a few years ago when what I suspect was their studio archive was being sold off. But even then, whenever we’ve seen and bought other COI posters they’ve been by them too – like this Keep Britain Tidy design by Reginald Mount.

A search of auction houses and archives like VADS reveals pretty much the same pattern – much Mount/Evans and Mount, very little else from the COI.

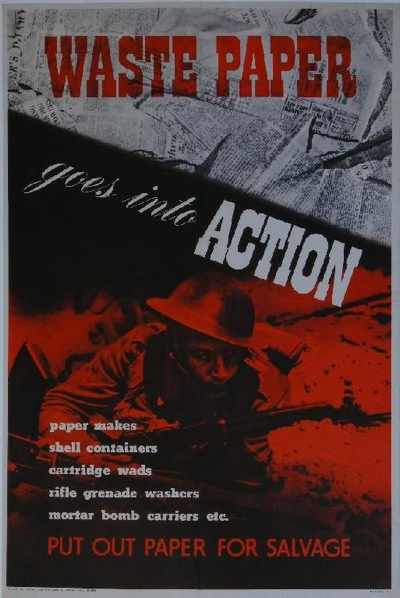

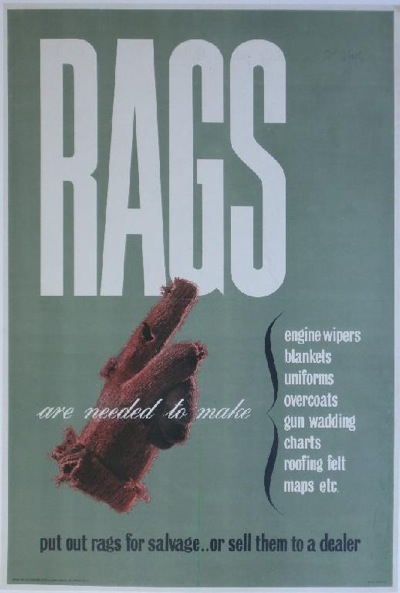

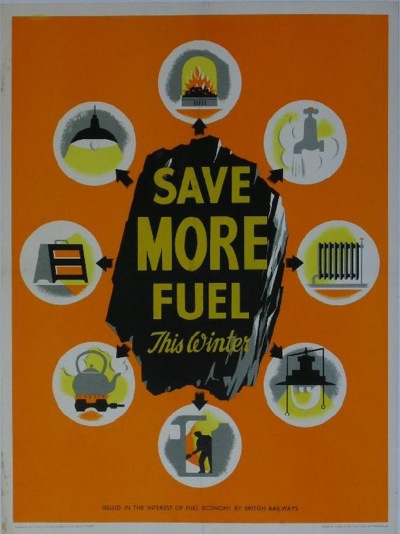

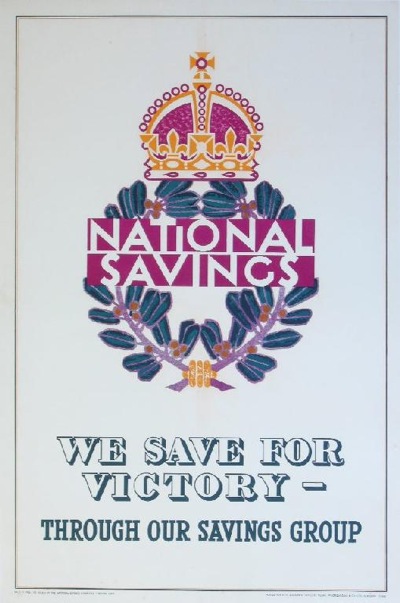

One reason for this may lie in the history of the COI itself. The Central Office of Information was formed in 1946 as a replacement for the Ministry of Information, which had produced most of the government’s publicity and propaganda requirements during the war. But for many people, propaganda of any time was seen as fundamentally not British and unsuited to a democratic state – i.e. this was something that the Nazis did and therefore, by definition, we shouldn’t. It could only be justified by the needs of war, and so the Ministry had to go at the end of hostilities.

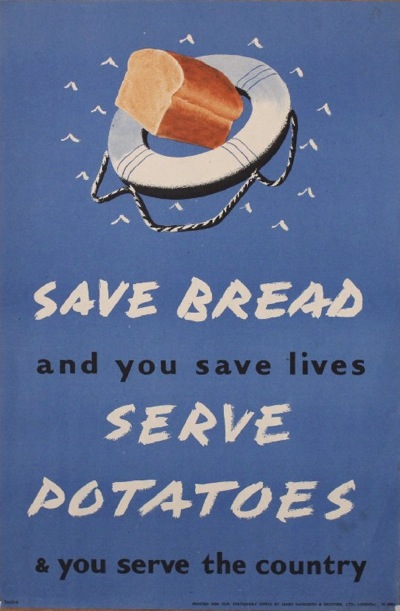

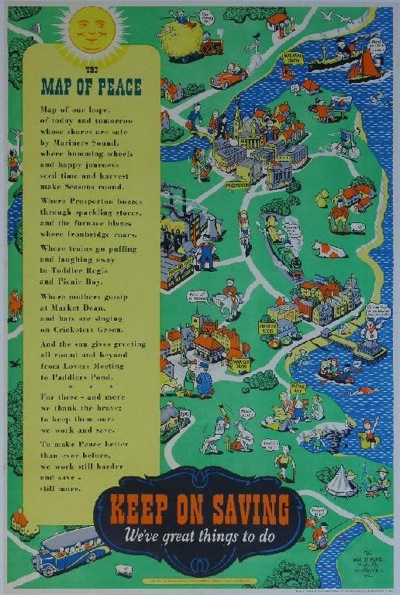

The problem with this was that the war itself didn’t finish so neatly. Austerity and rationing continued right into the early 1950s, and indeed was stricter in the late 1940s than it had been during the war. This in turn meant that much of the wartime instruction and exhortation to work hard and make a nutritious meal out of little more than cabbage had to carry on too. So when the Central Office of Information was founded, it had quite a lot of work on its hands, and I suspect that many of those artists worked for the COI in those early years.

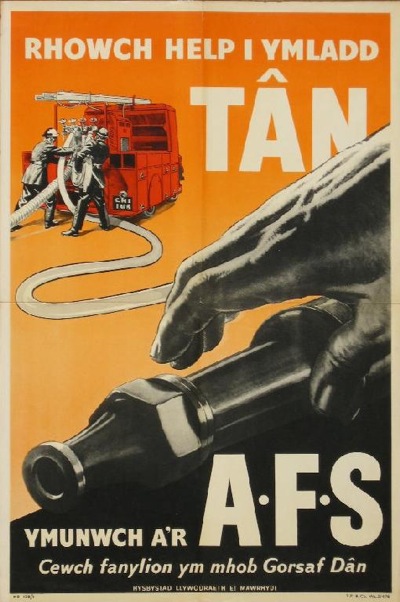

However it’s very hard to tell which these are; my suspicions are that most get lumped in under the heading of ‘World War Two’ posters. For example, I’ve seen both of these posters, by Lewitt-Him and James Fitton respectively, dated to 1947 rather than during the war itself.

Neither of these would have been produced by the COI, since the Ministry of Food ran its own posters and publicity throughout the war and I can’t imagine changed that afterwards, but they are good examples of how the wartime messages carried on past 1945. The only COI poster I know of which is definitely from this period is by Dorrit Dekk.

Dorrit Dekk only started producing posters in 1946, when she was demobbed from the WRNS and went to work for Reginald Mount at the COI, so this must be from between then and 1948 when she left. But without knowing this biography, it would be impossible to date the poster and it too would probably be ascribed to the war years as well. So I imagine that vast swathes of the COI’s early output has either disappeared, or been labelled as ‘wartime posters’ and, unless someone puts in a formidable piece of archival research one day, will never be known. I also suspect that those were the posters designed by that great list of artists in the book.

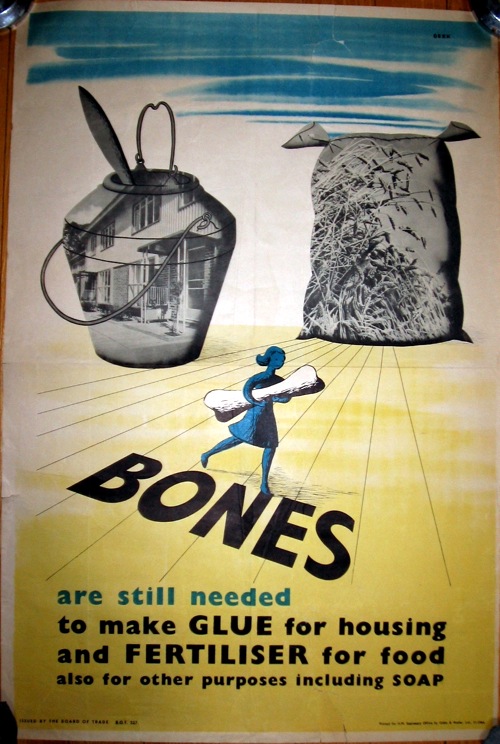

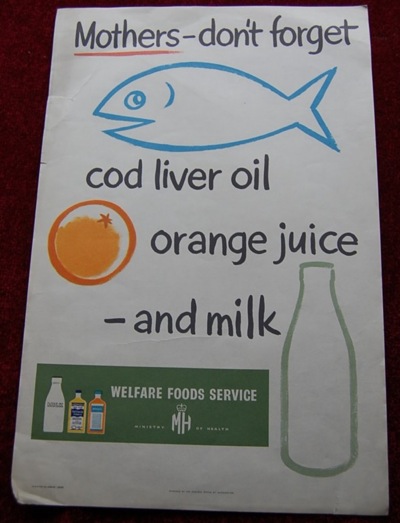

As the years went on, the need for government publicity decreased – although this anonymous COI poster is reminiscent of wartime appeals.

Judging by her hairdo, I’d put this at quite soon after the war anyway, but I’d be interested to hear if anyone else knows more.

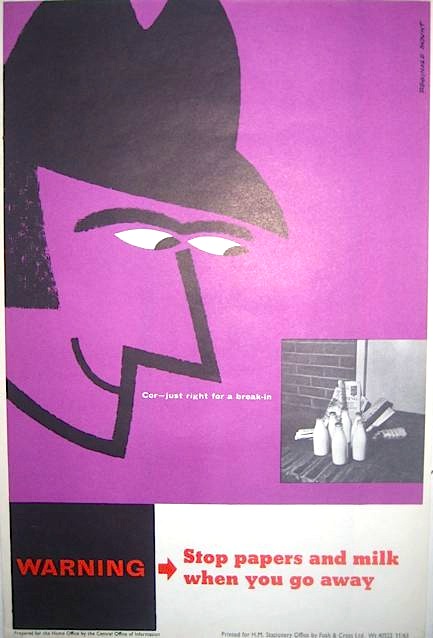

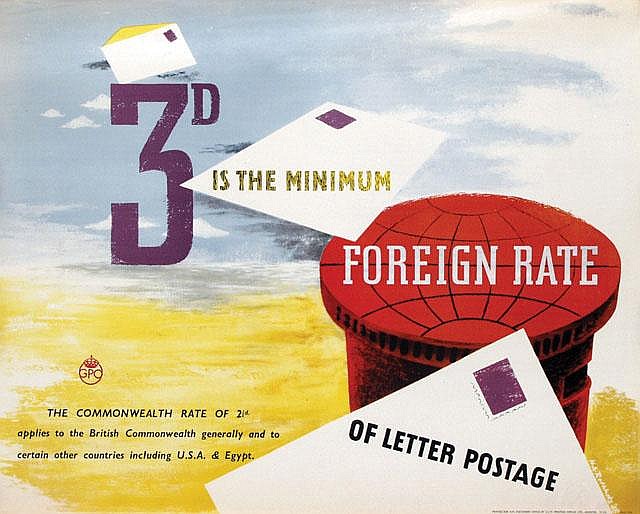

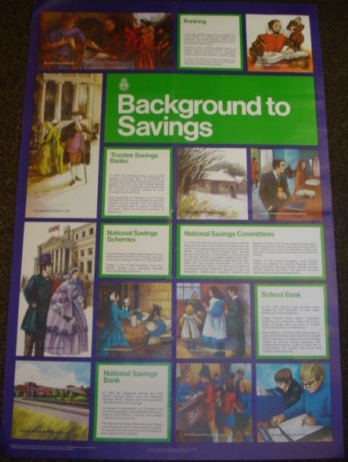

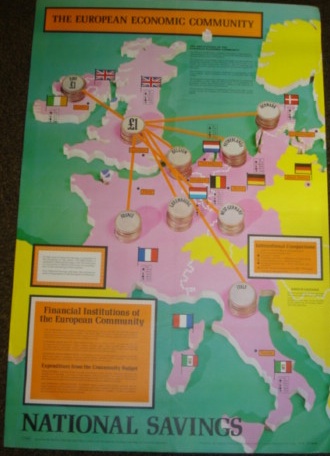

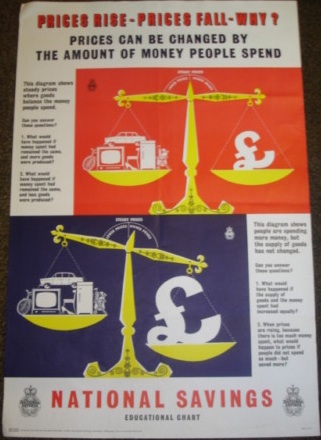

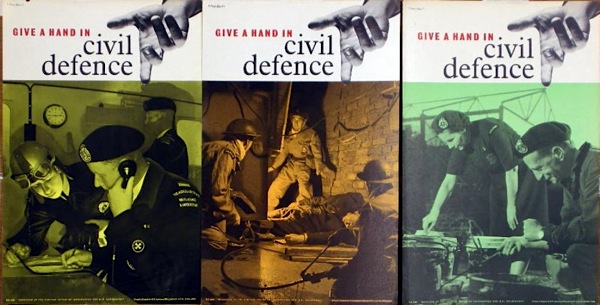

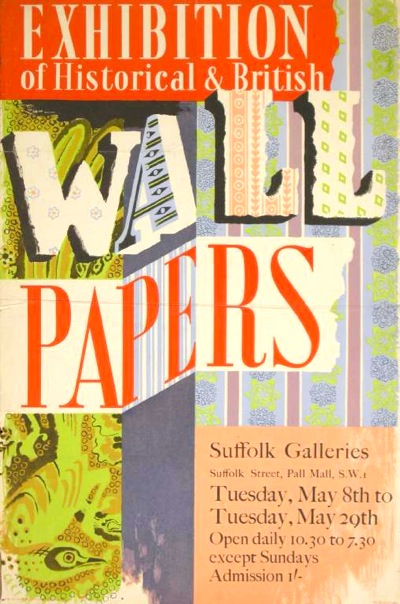

By the late 1950s or early 1960s though, the government just didn’t have as much to say. Get a passport on time, don’t drop litter, smoke a bit less. Don’t drink and drive. And remember to tell the milkman when you go on holiday.

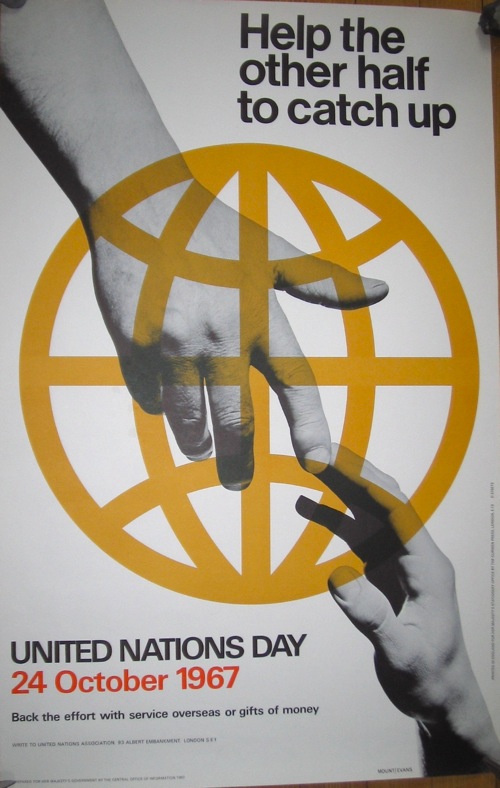

It doesn’t have quite the same heady excitement as the war years. Although the designers were allowed out for a few digressions, such as United Nations Day.

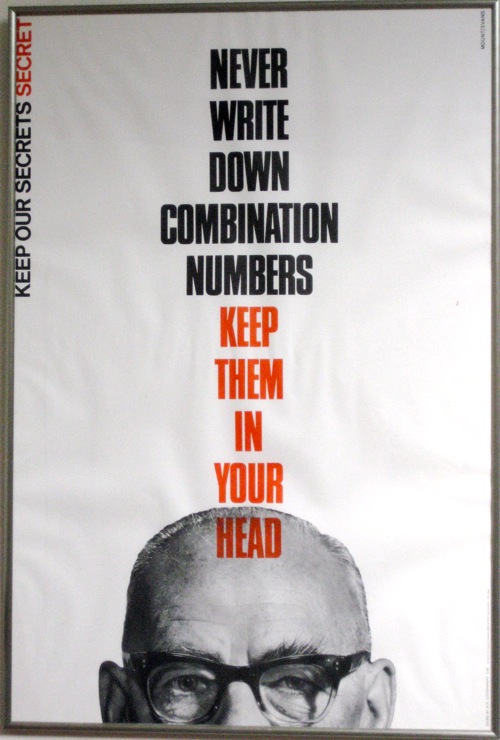

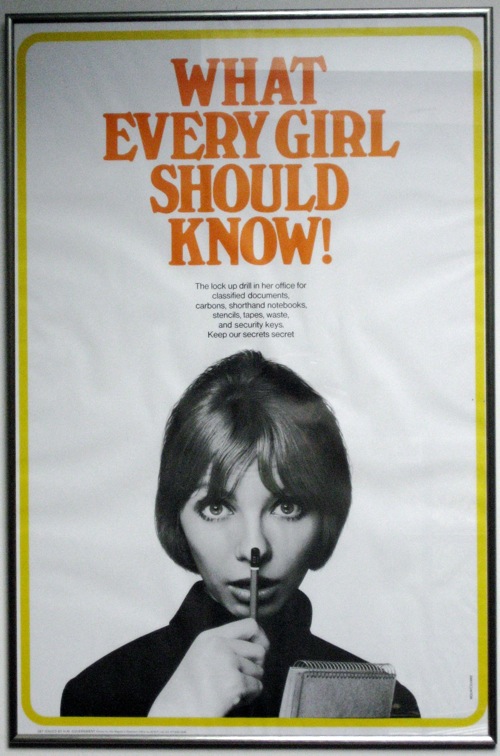

Not every COI poster was aimed at the general public either; Mount/Evans also produced a number of internal campaigns for the government, most notable ‘Keep Our Secrets Secret’ which I’ve mentioned before on here but which are so excellent that I can’t resist posting one more time.

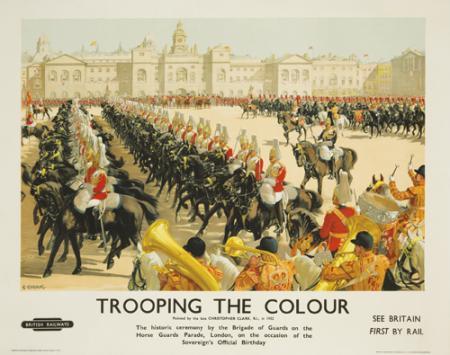

The other reason why there were fewer posters, of course, is that they were no longer the biggest game in town. More and more, the COI’s main campaigns were conducted through short films, whether in the cinema or in public information slots on the television. (Should you be interested, the National Archives have put tons of these online for your amusement). Only the less important messages like UN Day or internal communications would have been put out by posters alone.

But all of this has now gone, and every government message will just be put out by advertising agencies and be indistinguishable from commercial campaigns. Perhaps one day someone will produce an illustrated and possibly even interesting history of the COI, to show us just what design classics they did produce in their heyday.