I’ve been thinking a lot about hoarding recently – of various different kinds – which reminded me that this post probably deserved another airing. Two questions, has any more been written on this subject, and just what is the etymology of a poster hoarding anyway?

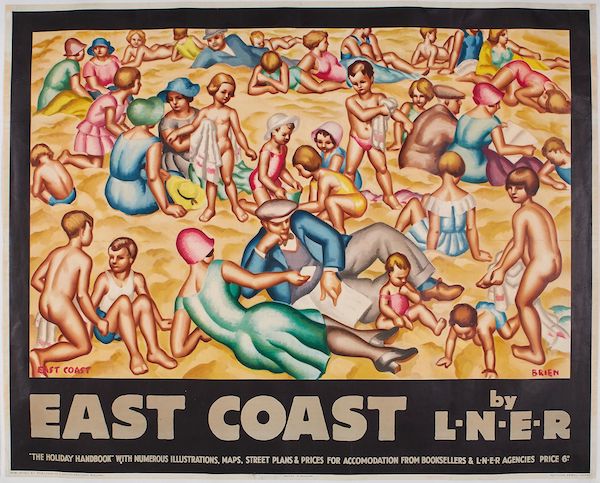

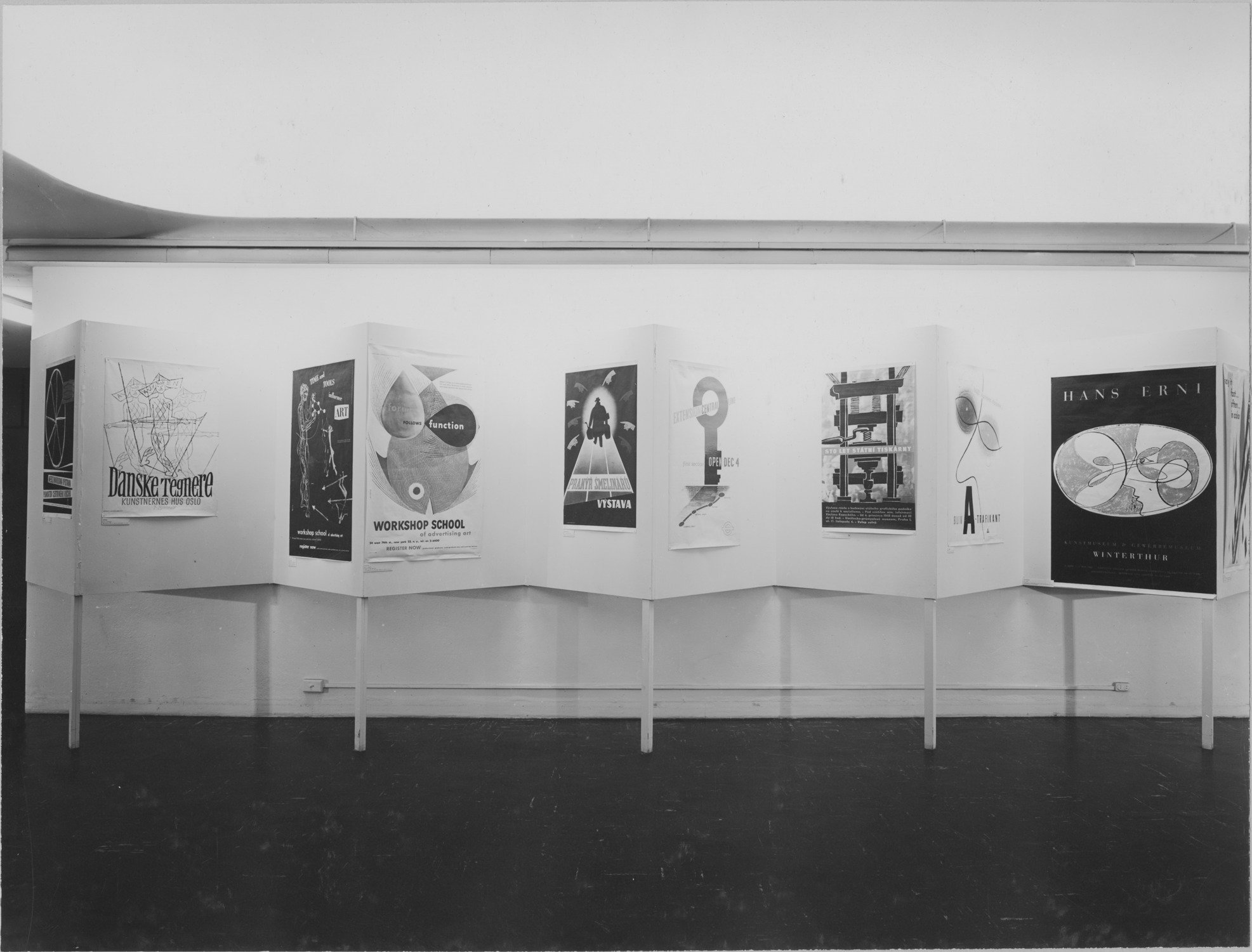

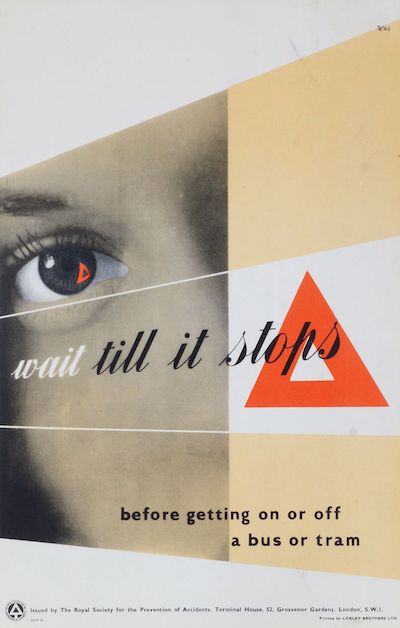

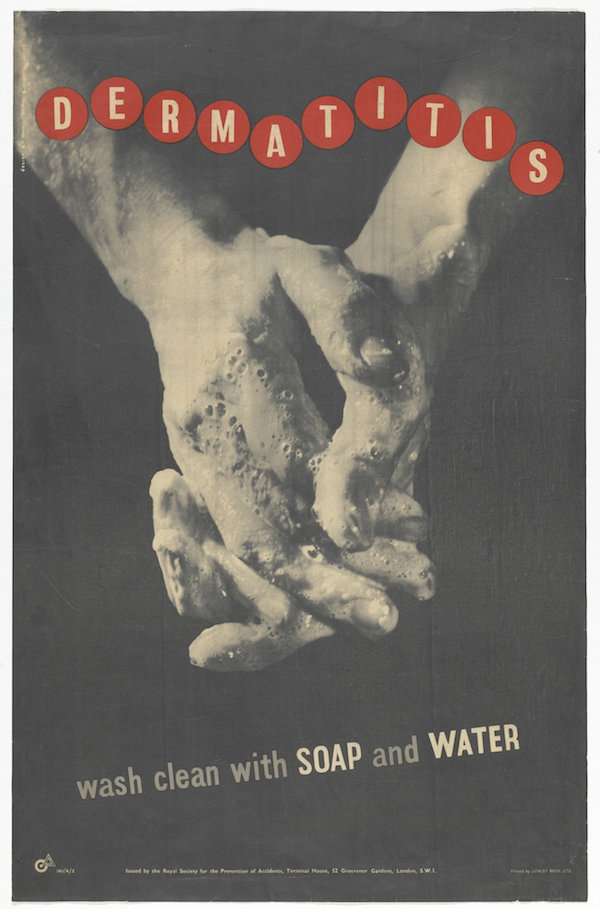

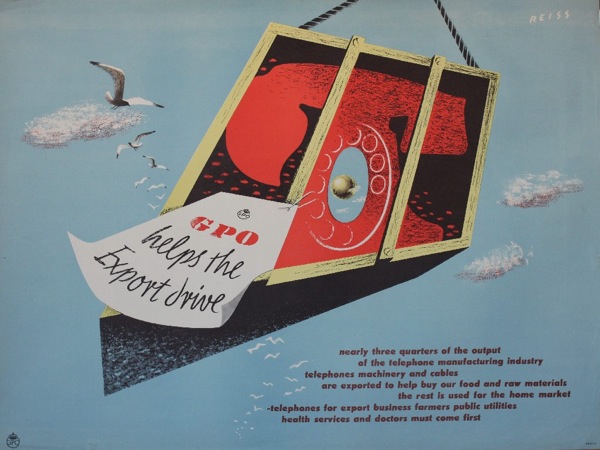

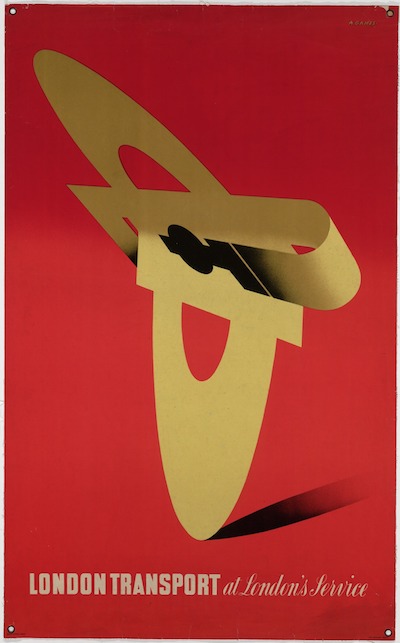

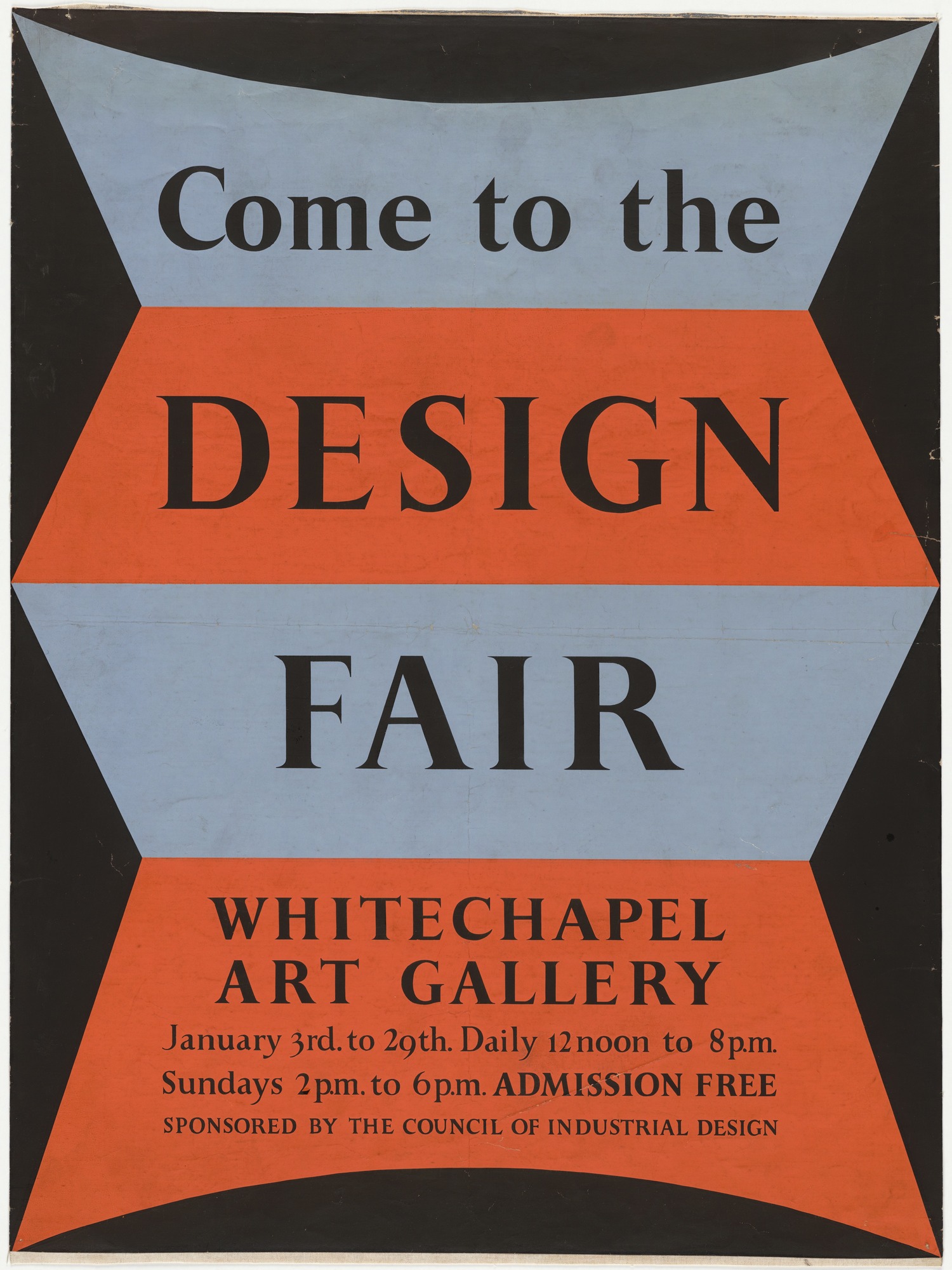

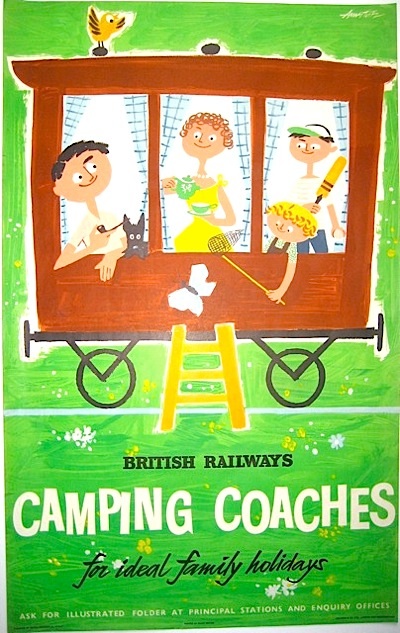

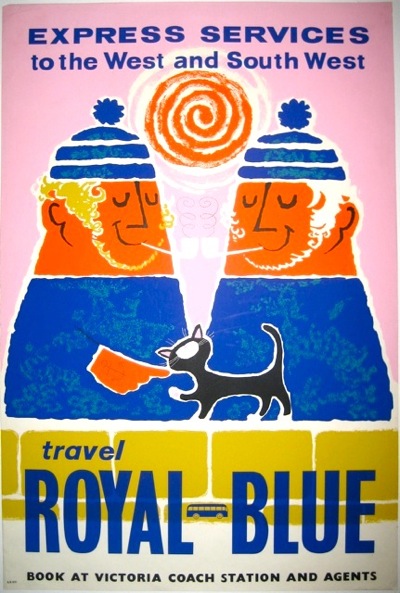

What do these four posters have in common?

John Burningham, London Transport, 1961

Andre Amstutz, British Railways, 1956

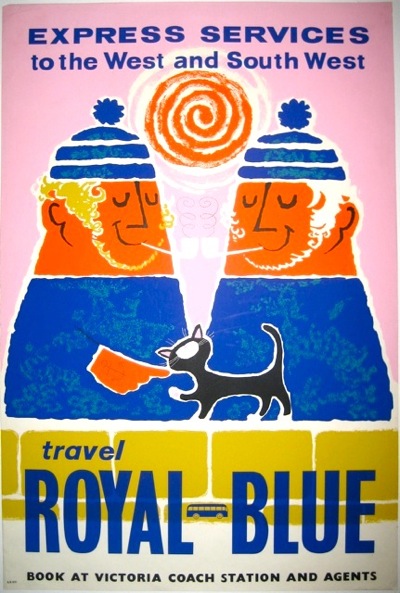

Daphne Padden, Royal Blue Coaches, c. 1957

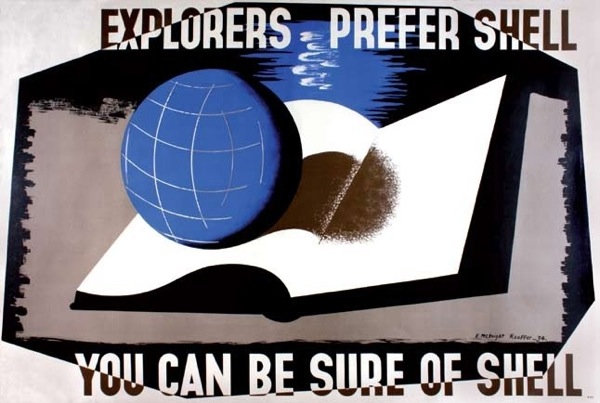

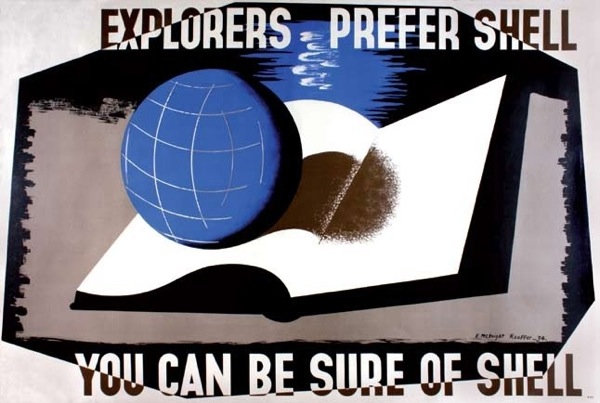

Edward McKnight Kauffer, Shell, 1934

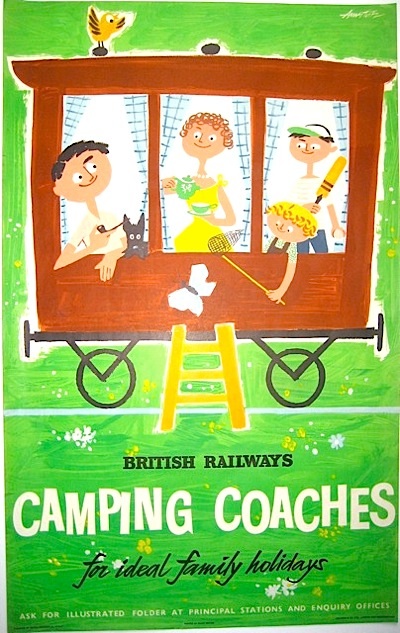

Well, three out of the four of them are on the walls here, but you’re not really expected to know that. Perhaps more to the point is that they represent four out of the five areas of ‘collectable’ posters: railways, London Underground, Shell and coach* posters (the fifth for me would be World War Two posters, for what it’s worth).

*This may be wishful thinking on my part, but we do seem to have quite a lot of them now (thanks to Malcolm Guest, mainly) and so they are at very least collectable by us. Anyone else?

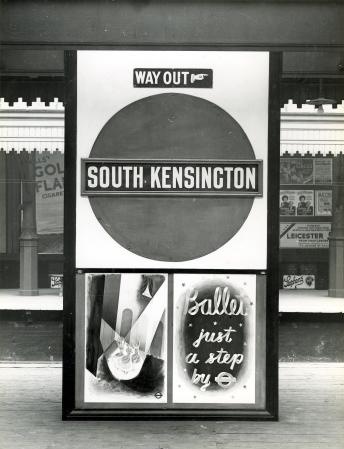

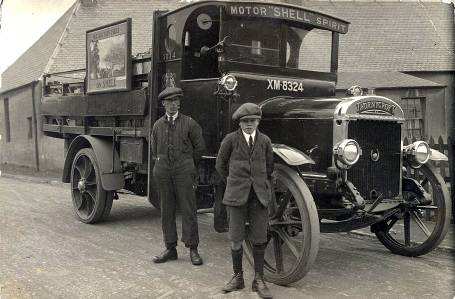

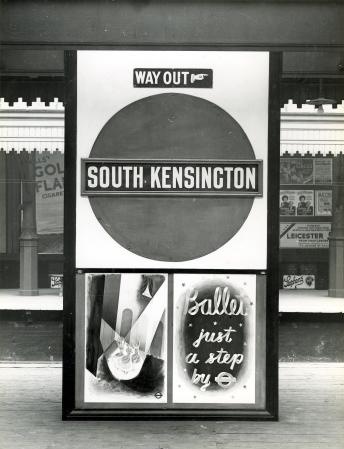

But those four areas also share something more than just being collectable. In each case the companies they are advertising owned the hoardings that the posters went on.

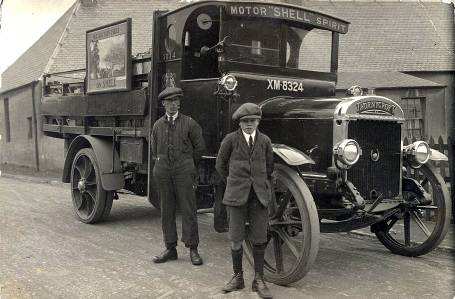

That’s reasonably obvious for the bus, tube and train stations – but Shell posters were also designed to be displayed on the vans which delivered petrol to the garages.

Now set down like that it doesn’t seem like so much of a blinding revelation. But it isn’t, as far as I know, something which has been much commented on. And yet it had a big impact on their posters.

The most obvious example is that all of these companies had a much greater incentive to produce posters than anyone else. Not only was this in effect a subsidised form of advertising for them, but they also needed to churn them out in order to fill up spaces when they hadn’t sold enough commercial advertising.

Here’s Enfield West Station in 1934, with a McKnight Kauffer poster for Eno’s Salts clearly visible on the hoardings.

They also continued to produce posters in great numbers later on, when the poster had ceased to be the main medium for advertising, because the spaces were still there and still needed filling.

In addition, there may have been more reason for the companies to produce ‘artistic’ and possibly also more subtle posters, because this will have a very direct effect on the station environment. Although this probably worried Frank Pick more than it did the owners of Victoria Coach Station.

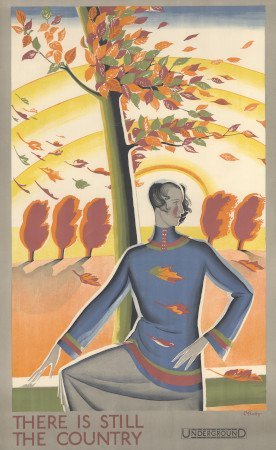

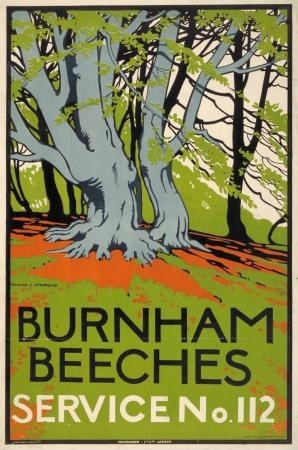

I’ve also read an interesting suggestion that in the early days, London Underground commissioned lots of posters of wide open spaces to counteract the perceived claustrophobia of the tube, but I don’t think there’s any proof of that.

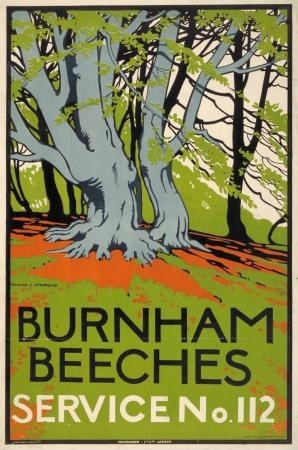

Burnham Beeches, Walter Spradbury 1912

Now originally this was going to be my only point, that all of these people owned their hoardings and so had to invest more in posters and poster design than other companies, which in turn may be one reason why their posters are collectable. And that this hadn’t really been noted until now.

But then I found a really interesting article by David Watts (insert Jam or Kinks record into your head here as you wish) about pre-war depictions of Yorkshire in railway posters. It’s an exemplary look at how posters worked and were consumed, rather than just what they looked like, and backed up by a ton of research. The world of posters could do with a lot more of this kind of rigorousness (not that I’m volunteering to read 200 volumes of railway company internal correspondence, you understand).

One of his points is that the context of railway posters is all-important. They didn’t need to have pictures of trains on, because they were posted up in stations. The fact that they were advertising railway travel rather than just the location pictured could be asssumed.

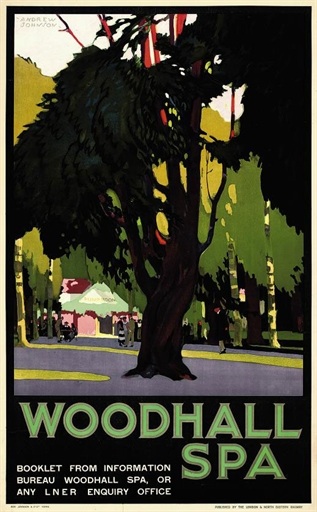

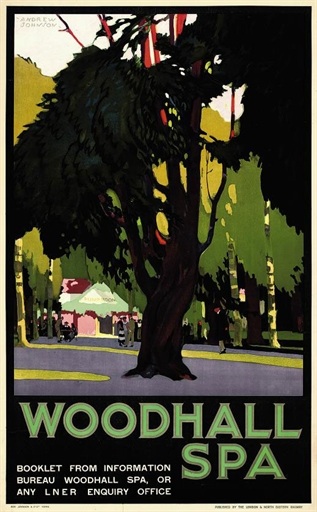

Andrew Johnson, no date

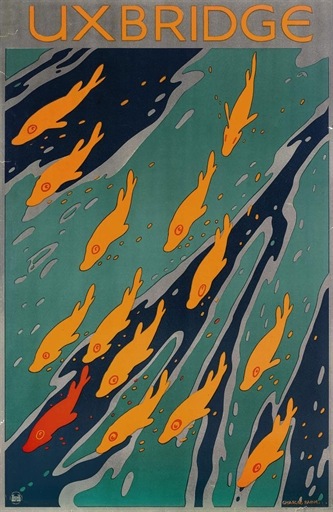

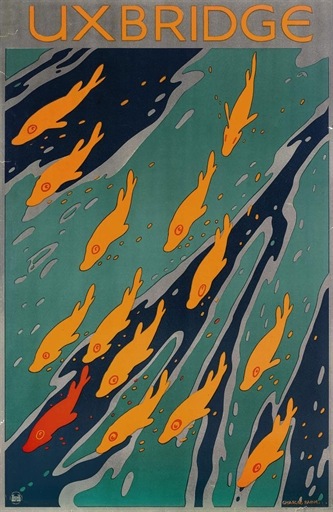

The same is true of London Transport posters. They can just say Go to Uxbridge.

Charles Paine, 1921

That you’d use the underground to do so is implicit in the fact that the poster is displayed at a tube station.

But, as Watts points out, this contextualisation of the posters has other implications.

…omitting any visual reference to rail travel allowed posters to be detached easily from their ‘mundane commercial purpose’.

So the companies, as I’ve mentioned before, could promote their posters as examples of good design for the masses, and even as fine art, in part because they didn’t need to say Go By Train in large letters at the bottom.

Now Watts argues that this made railway posters at least a rather poor form of advertising. And he does put forward some evidence that the train companies themselves thought this way by the early to mid 1930s too. Images of trains, or at least the idea of train travel did become more prominent after then – as in the Tom Purvis that is coming up at Christies next month.

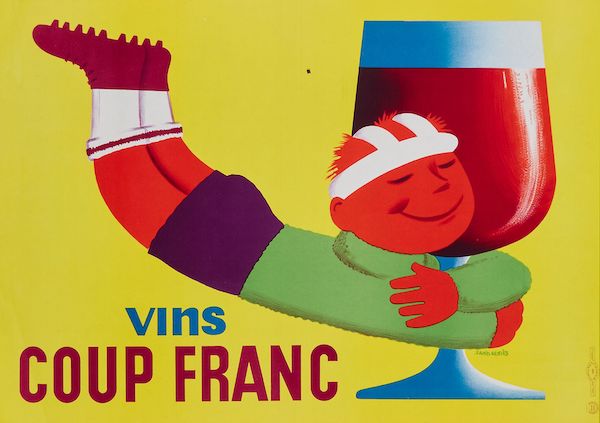

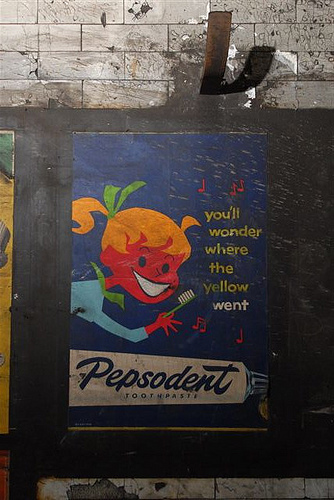

But he also says – and I think that this is entirely right – that the fact that the posters were semi-detached from their commercial purposes is one of the factors that has made them so collectable. They exist in a limbo between fine art and outright commercialism, and are so more appealing than an advertisement for Eno’s Fruit Salts or Gilette Razors.

Although it is worth remembering that it’s only because the companies were promoting them as ‘art’ that these posters are available to collect at all. Shell, Underground and railway posters were all available for sale to the public when they were first produced, so they do survive in attics and collections, while the most commercial billboard posters weren’t and so aren’t. (I’ve mentioned this in passing before, but really ought to pull together all the sources on this one day, because it’s not said often enough. Even here.)

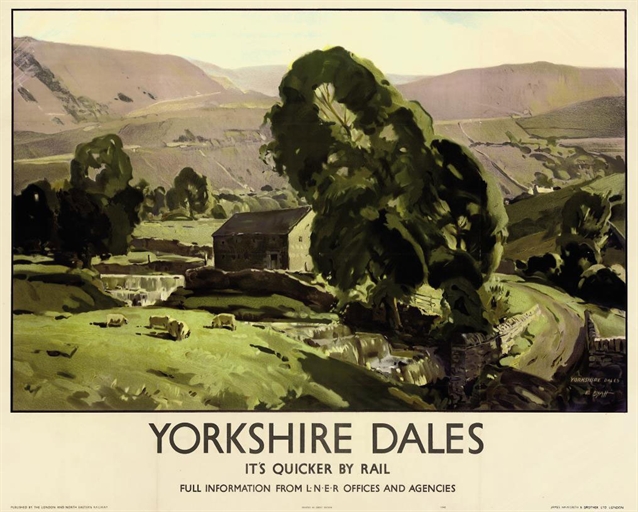

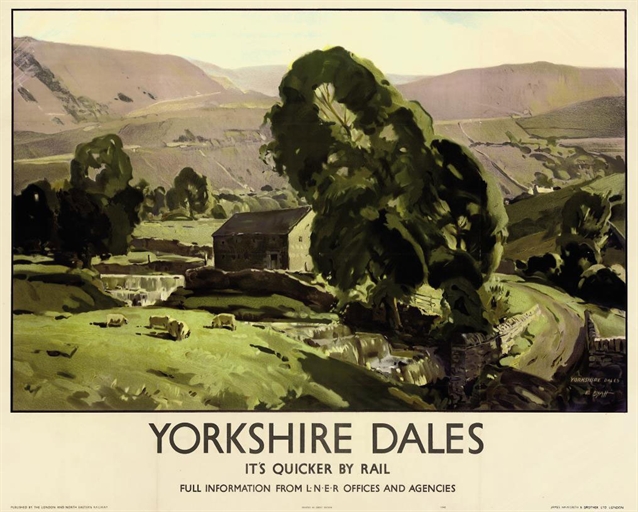

But I think there’s also another way in which the context affected railway posters in particular (although the same is probably also true of London Transport and coach posters to some degree as well). Watts points out how much the railway posters are selling an image of ‘deep’ England, by which he means an archaic, un-modernised and highly rural vision of the countryside. Now whenever this vision is called up at this time, it is almost always intended as a direct contrast to the modernity, ribbon development and speed of the 1920s and 30s.

Edwin Byatt, 1940

But in the railway station, that contrast is always there anyway. Most of these poster would have been displayed in an urban setting, and even where they were put up at local stations, there was the machinery and bustle of the railway itself. So the posters are also using their context to suggest that there is an alternative, an escape. And that’s something else that they don’t need to spell out in words at the bottom.