There’s a certain inevitability about the fact that now I’ve written the Home Front Posters book, a whole heap of new information about World War Two posters has popped up in various places. This isn’t entirely a painful discovery, and not just because I am now resigned to the fact that while research could go on indefinitely, books do have deadlines. Because today’s exhibit is that particular joy, a brand new archive.

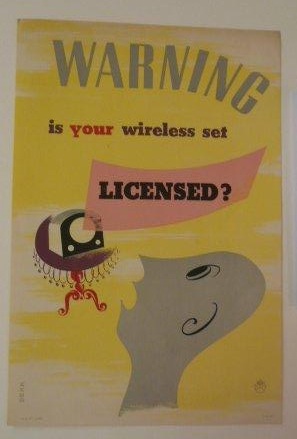

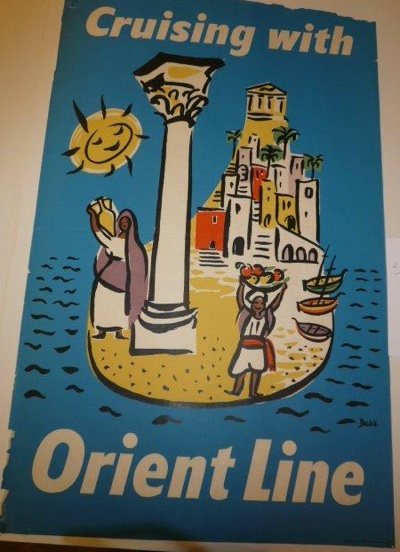

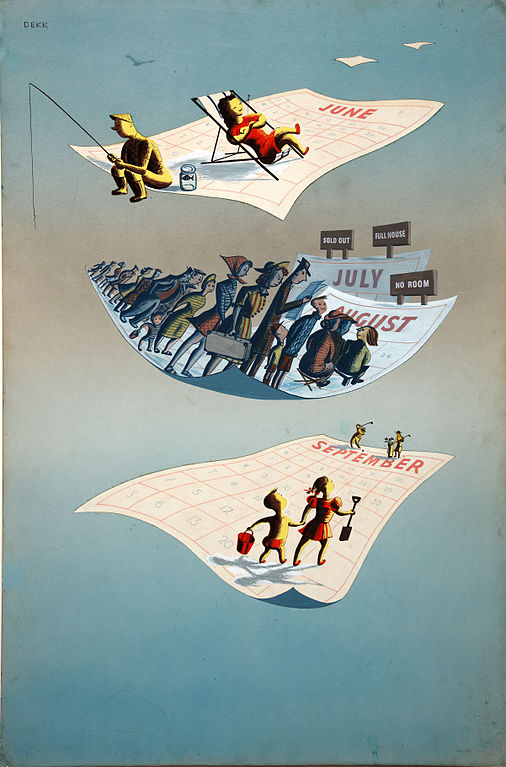

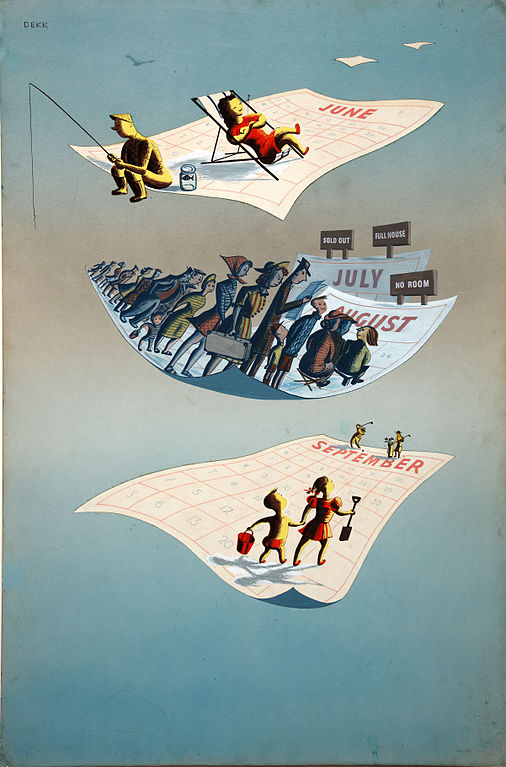

What’s happened is that the National Archives have digitised a significant chunk of their wartime posters and are distributing them via Wikipedia. (There’s a full explanation here if you want to know more). It’s very exciting because there are a large number in there that I’ve never seen before. Here’s a rather nice Dorrit Dekk to begin with.

This isn’t just an act of altruism but also a kind of crowd-sourcing, because the archives don’t have much information about many of these posters and they’re asking for people to help with everything from attributions to translation of foreign-language posters.

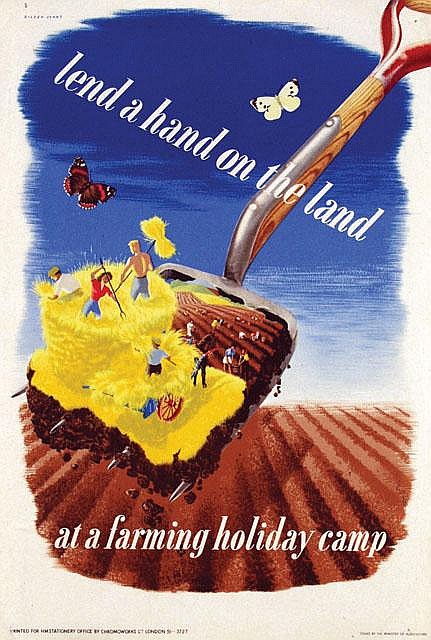

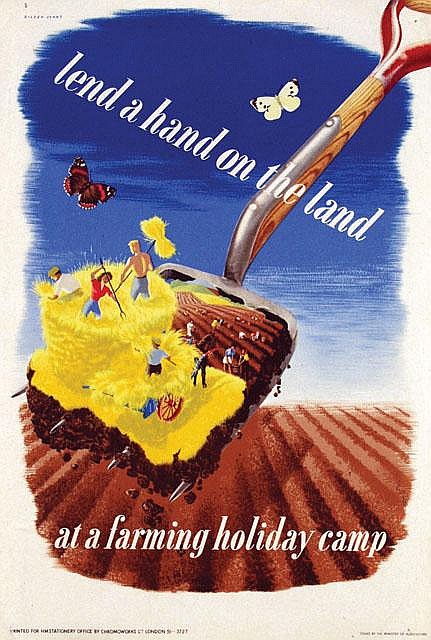

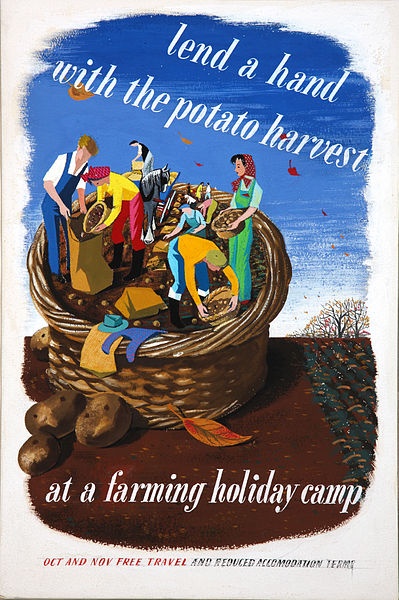

Part of the challenge, particularly with matching artists to designs is that these aren’t printed posters but the original artworks, quite often without the signatures that the finished item would have. So it ends up being a process more like finding the provenance of a painting. For example, we have this Eileen Evans, signed.

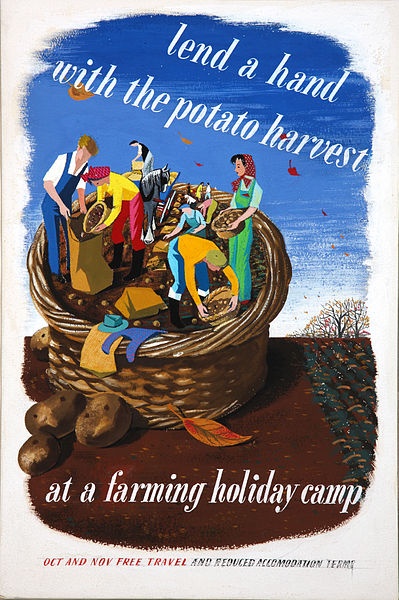

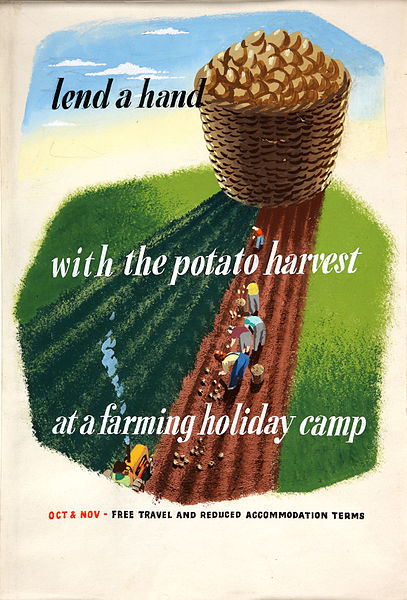

Which makes it a fairly reasonable guess that these two posters in the National Archives are also by her.

In fact I’m confident enough about that to have amended the description for each of those.

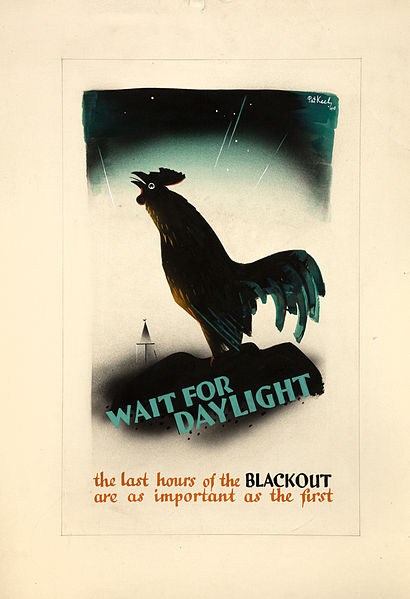

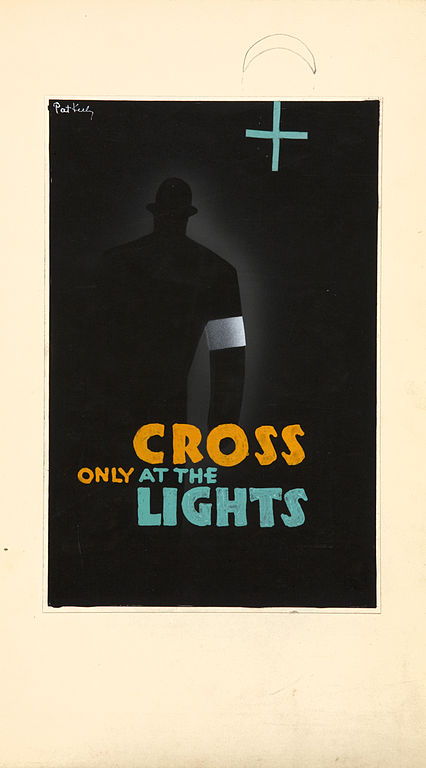

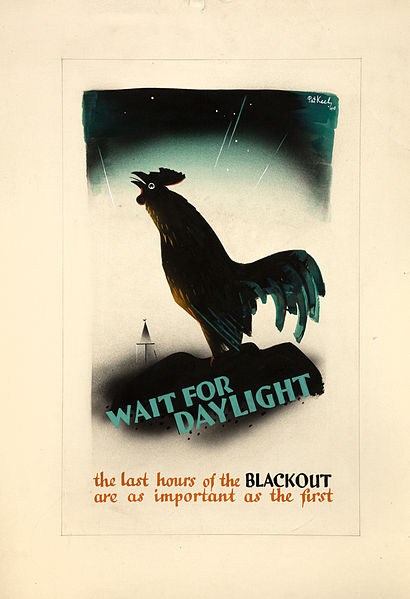

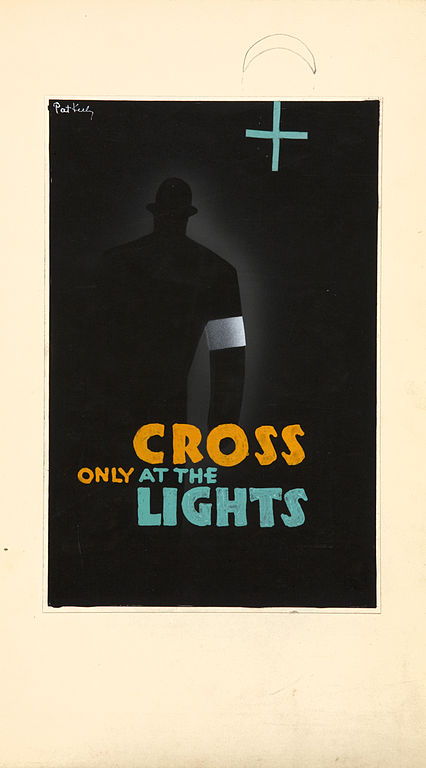

Only 350 of the 2,000 designs in the National Archives have been uploaded so far, but what’s already striking is how many of these I’ve never even seen before. Take this Pat Keely for example.

I think he owes McKnight Kauffer an acknowledgement on that one. Keely’s quite well-represented in the selection that are up so far, again often with previously unseen posters.

What’s difficult, though, is to interpret what these previously unknown designs actually mean. Are these for posters which were printed but are as yet unreported – whether that is because a copy never survived, or perhaps does exist but has not yet been digitised by the Imperial War Museum? Or are they designs which were not actually ever produced? In many ways. my bet would be on the latter. Artworks which never went to the printers would be far more likely to survive.

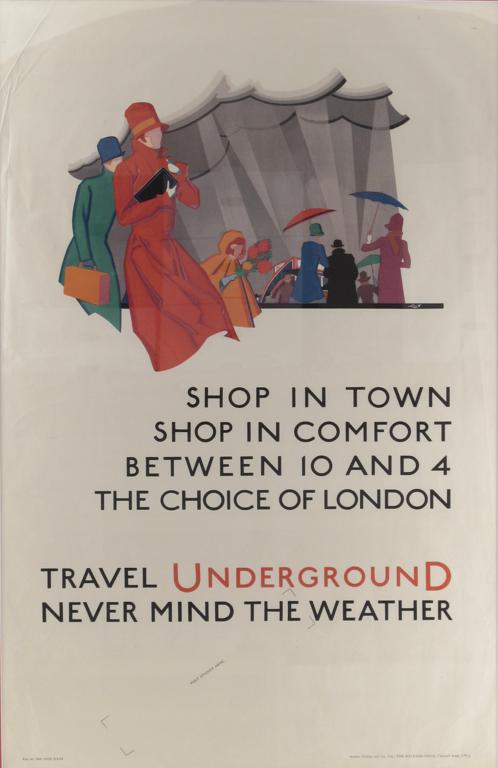

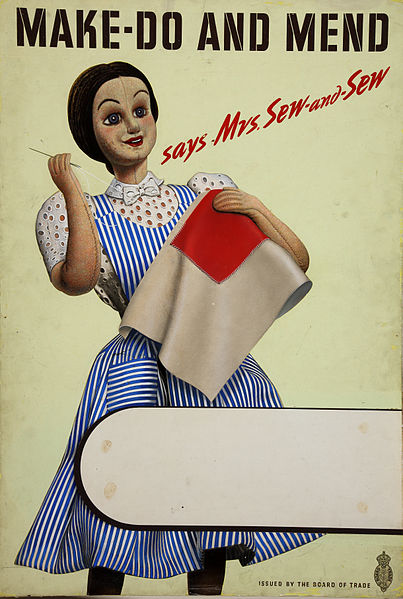

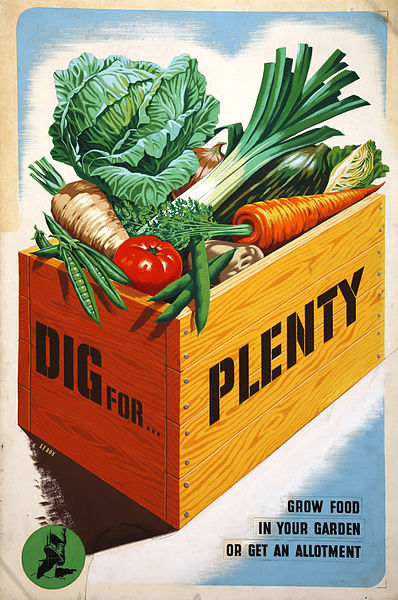

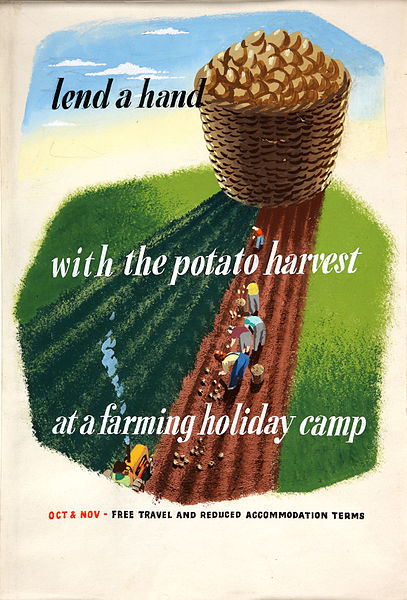

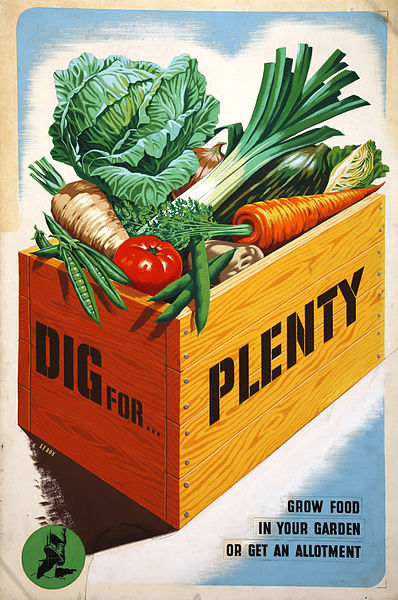

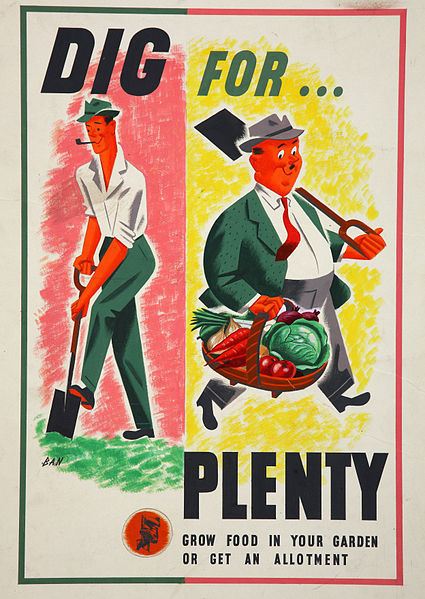

Then on the other hand, this artwork is in there, for a poster which was very definitely printed in quite large numbers.

There’s not an obvious conclusion to be had. Except perhaps that – because of wartime haste, limited record-keeping and the only accidental survival of what were intended to be very ephemeral bits of paper – we’ll probably never have the definitive list of World War Two Home Front posters, never mind their dates and artists.

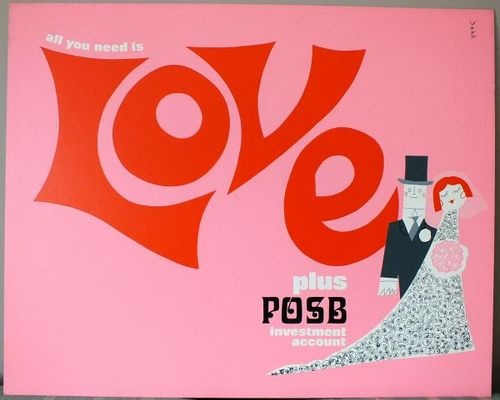

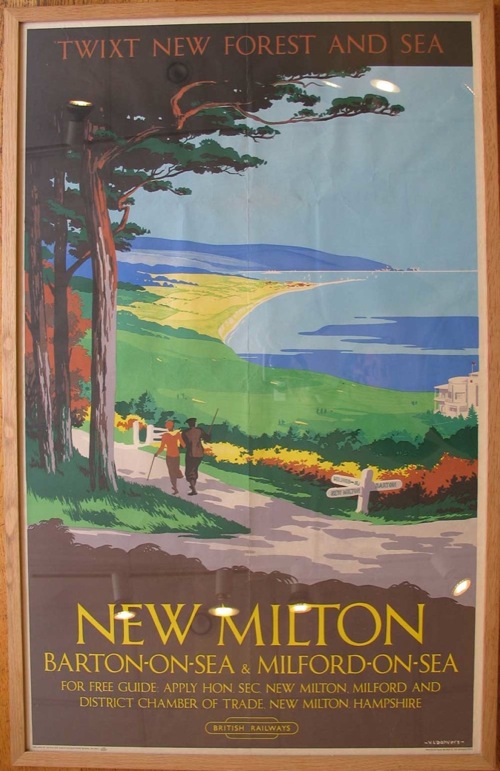

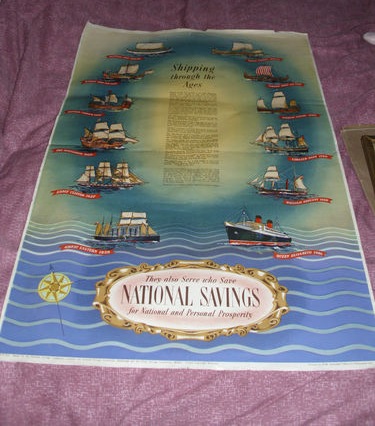

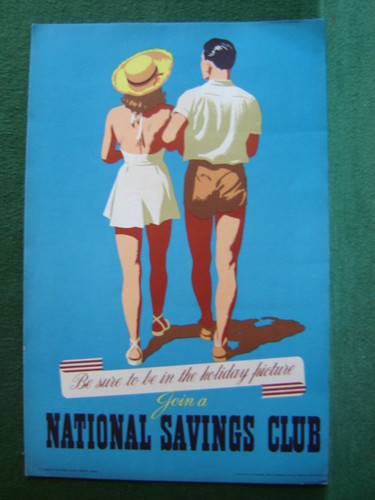

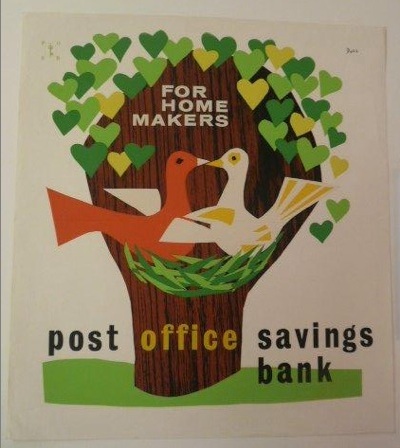

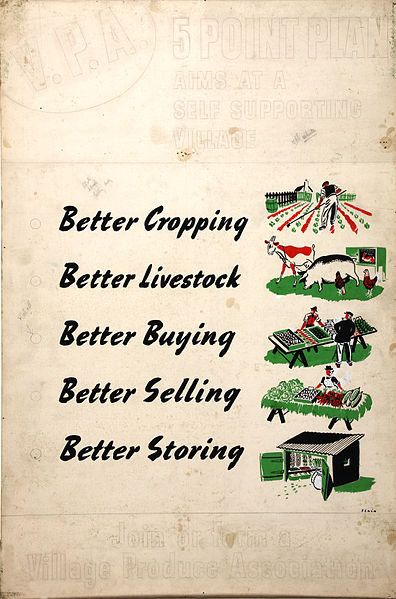

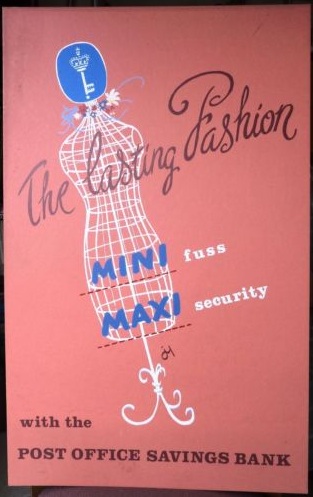

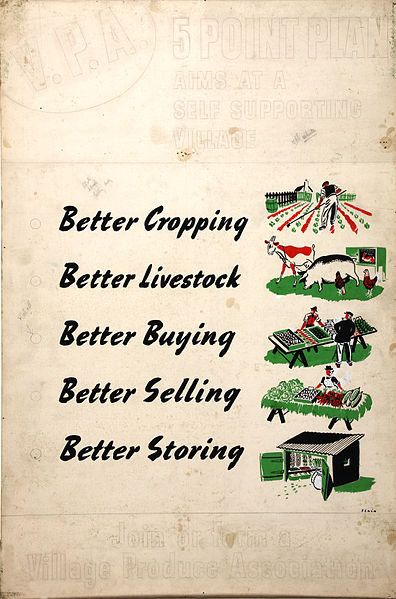

It’s also worth remembering that this collection is very partial. The artworks all came from the Ministry of Information, but they were by no means the sole source of posters during the war. Both National Savings and the Ministry of Food, two of the highest-spending departments at the time, commissioned their own advertising, so very few of their designs, if any, would turn up in the MoI’s archives. And that’s without considering other poster producers, from British Railways to the Army. Even so, there are still some delightful surprises in there. It may not be the greatest design ever – apparently by the mysterious Xenia – but I love the idea of Village Produce Associations a lot.

So I am very happy to report that Google reveals many VPA’s founded during the war are still going today. Hurrah.

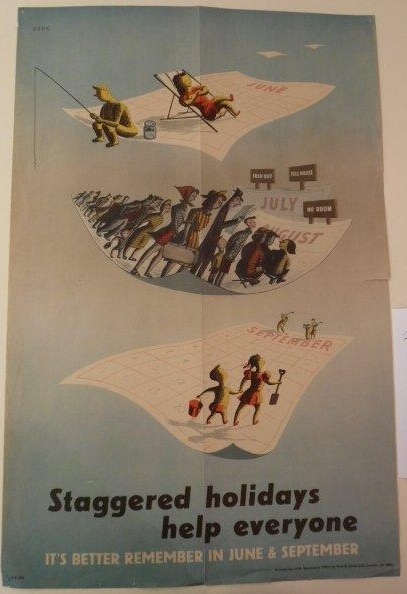

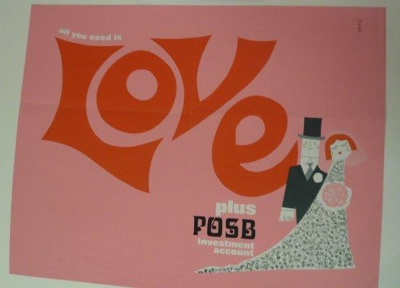

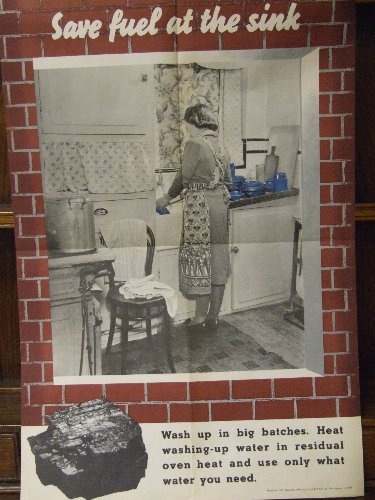

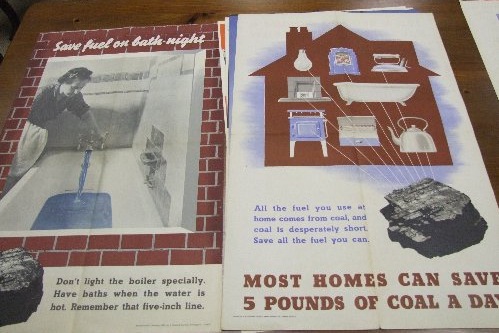

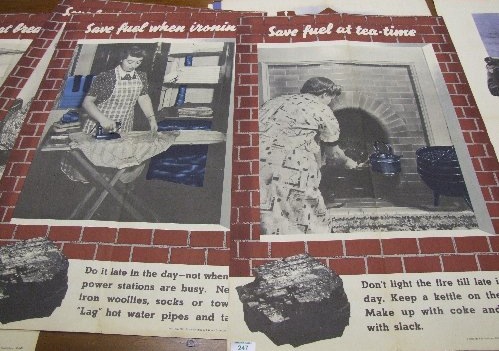

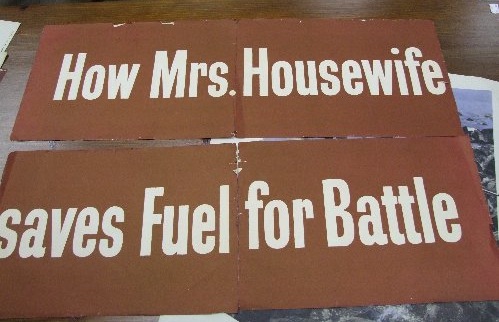

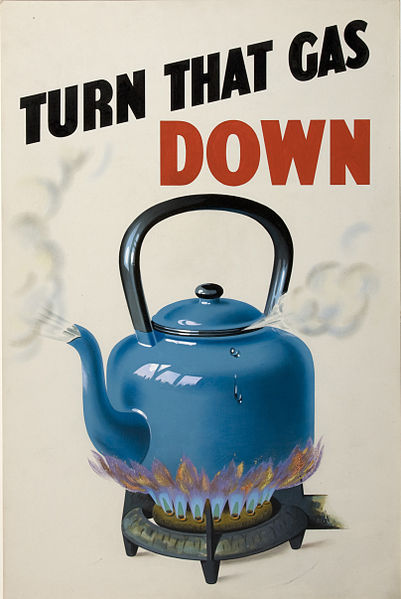

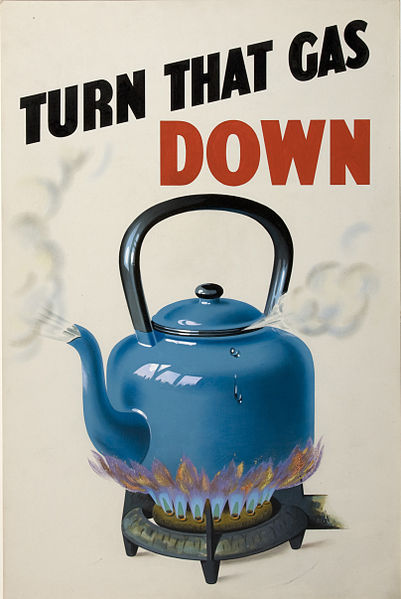

That kind of continuity after the war is also apparent in the poster designs. It’s easy to believe, as I’ve said on here before, that all wartime posters stopped as soon as hostilities ceased, but that’s far from the truth. Many campaigns, from salvage to fuel saving, just continued unchanged. This fuel saving poster – in the great tradition of bossy shouty slogans – could date from during or after the war.

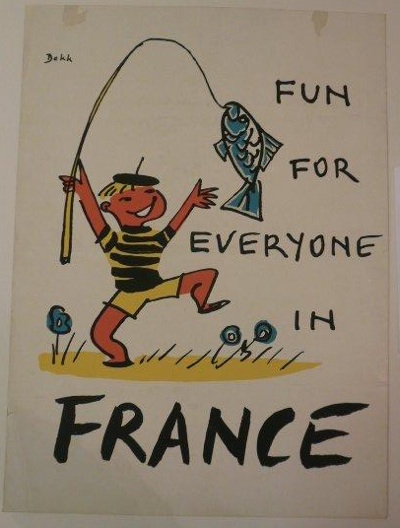

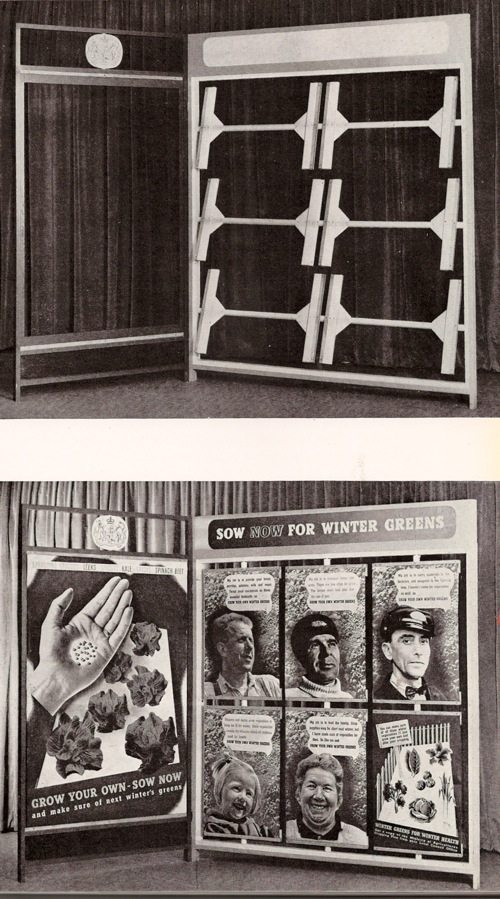

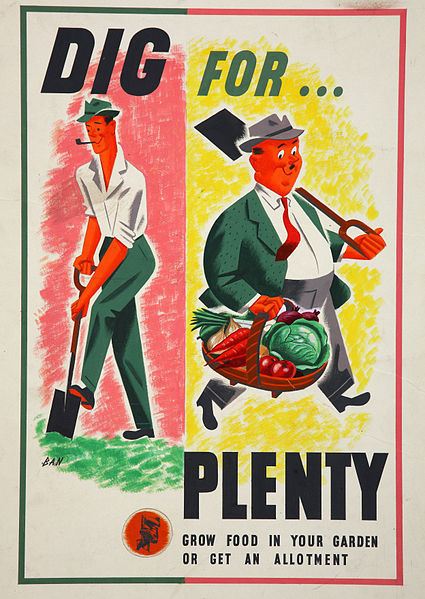

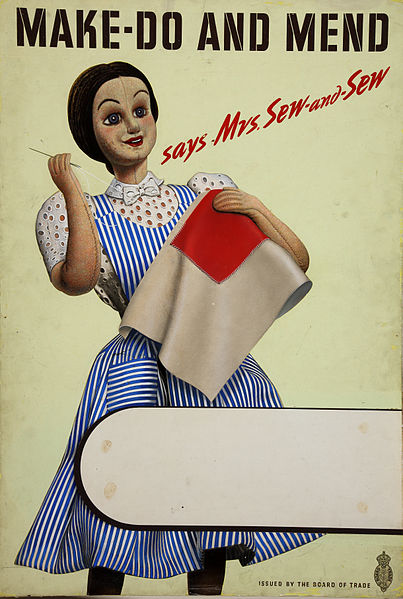

Other campaigns, meanwhile, were reversioned for the peace.

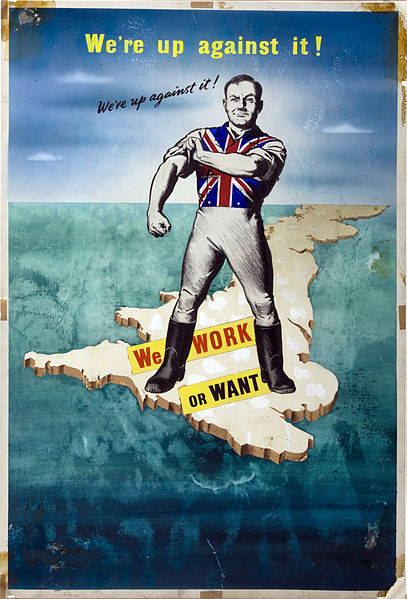

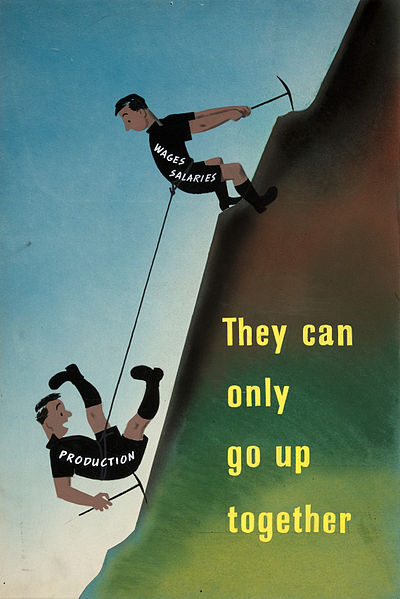

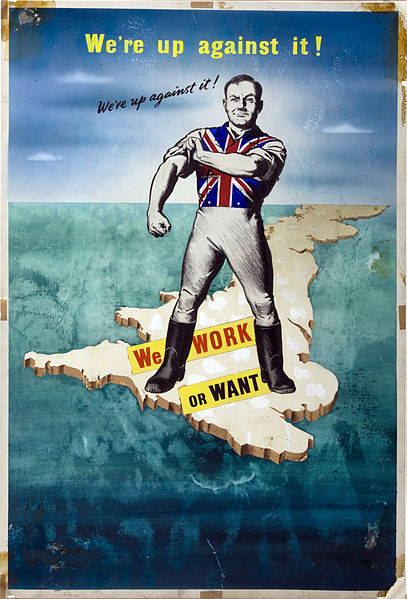

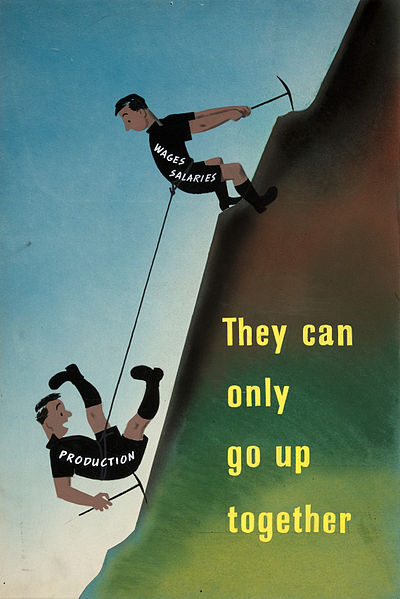

It’s also fascinating to see some of the very definitely post-war designs produced by the new Labour Government to persuade people that the continuing austerity was necessary – a much harder job than wartime propaganda.

These seem to me to be much rarer than the wartime posters, presumably because, by this stage of post-war austerity, no one at all wanted to keep them as a souvenir.

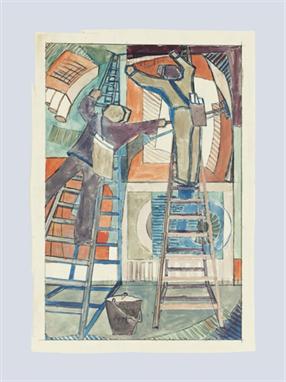

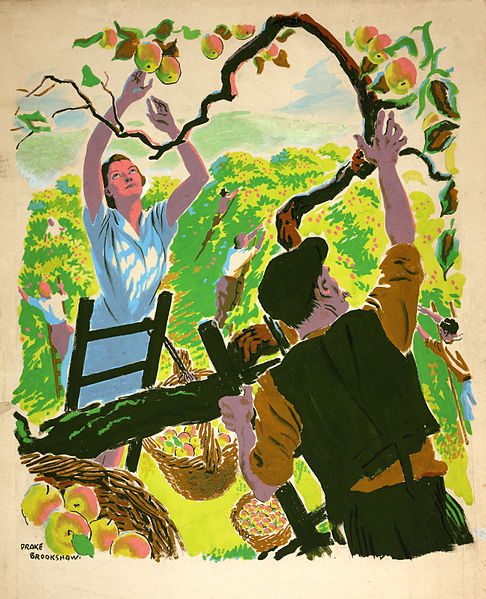

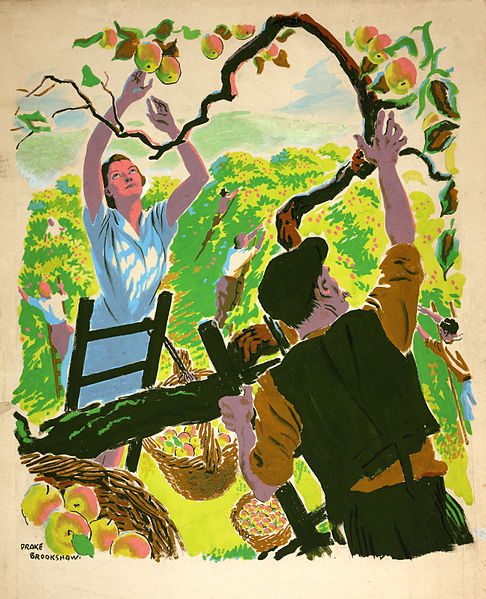

There’s plenty more to be seen in there too – including this Percy Drake Brookshaw artwork for – well for what?

So why not take a look and see what I’ve missed out.